|

| The Thomas Legion |

|

| William Holland Thomas |

| Museum of the Cherokee. By the webmaster. |

|

| The Thomas Legion Flag in 2007. |

Thomas' Legion, also known as Thomas' Legion

of Indians and Highlanders, was the largest single military unit raised in North Carolina during the American Civil War (1861-1865). The legion consisted of infantry, cavalry, artillery, an Indian

battalion, and it fired the Last Shot of the Civil War east of the Mississippi. Commanding Colonel William Holland Thomas was the only white man to have served as a Cherokee chief and his cousins included President Zachary Taylor and President Jefferson Davis. The

Thomas Legion recruited Cherokee Indians, one of its soldiers was awarded the rare Confederate Medal of Honor, it served with General John C. Breckinridge (14th

Vice President of the United States and cousin to Mary Todd Lincoln), was assigned to the same division

as General George S. Patton's grandfather, and was the last Rebel unit to surrender east of the Mississippi.

With the determination of Thomas' Legion, Union forces never subjugated

Western North Carolina, and the command captured the Union occupied city White Sulphur

Springs (present-day Waynesville), North Carolina, and was perhaps the only unit to have seized an enemy held

city in order to negotiate its own capitulation. Whereas in 2003 the Last Surviving Union Widow died, her late husband had fought against Thomas' Legion some 140

years earlier.

Thomas' Legion of Indians and Highlanders

This organization initially totaled 1,125 men, but would soon consist of an

infantry regiment, two battalions, one of white and the other of Cherokee, two companies of miners and sappers, and an artillery battery, which

would be added on April 1, 1863. Levi's Light Artillery Battery, aka Louisiana Tigers or Barr's Battery, formerly served in the Virginia State Line Artillery before joining the ranks of the Thomas Legion. During the conflict, the unit would muster more than 2,500 officers and men, including the 400 Indians which formed the Cherokee Battalion. The size of this command varied however, as some of its companies were transferred to other units to meet the exigencies

of war. But the legion would gain Companies A and L of the battle-hardened 16th North Carolina, a regiment that

had served under the likes of Lee and Jackson. Unlike any given regiment consisting of some 1100 soldiers, the Thomas

Legion, which on a few occasions fielded some 2,500 strong, was a much larger fighting force and it resembled a

brigade. While this unit was never officially designated the 69th North Carolina Regiment, there are

75 references to Thomas' Legion in the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Hereinafter cited as

O.R.)

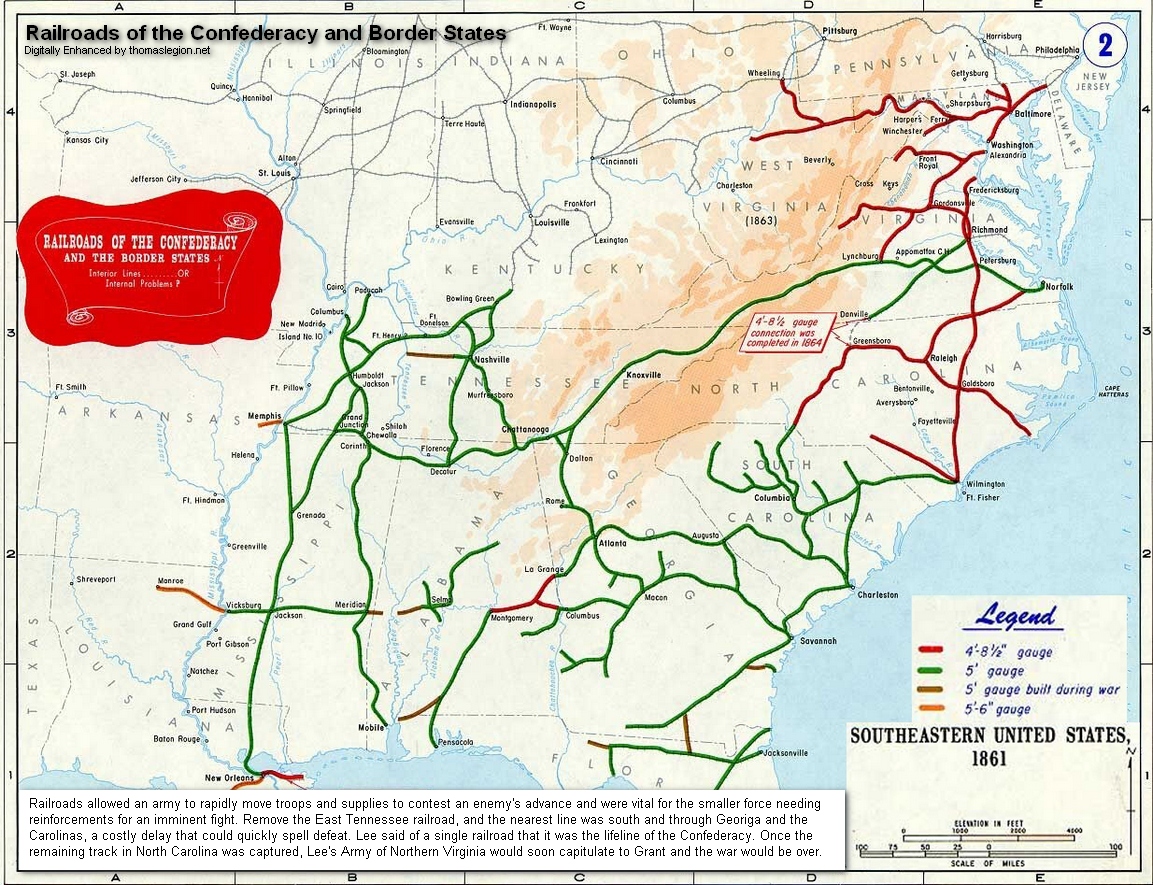

This independent

command initially reported directly to Brig. Gen. Henry Heth and provided invaluable

service in the defense of vital and strategic railroads, bridges and depots. Whereas the legion would spend a significant part of the conflict defending the sole railroad

in East Tennessee, it was a rather thankless and monotonous task and one that would never grace the headlines. But on the

other hand, when the Union army downed a bridge or tore up much track in the Volunteer State, it was front page

news. While the command was frequently tasked with tenuous provost duties, it often found itself engaged with

guerrillas, bushwhackers, and an ever emboldened Union foe.

In May 1864 the regiment of the legion was detached and moved to Virginia to participate in Lt. Gen. Jubal Early's Shenandoah Valley Campaigns before returning to North Carolina. The legion would fight skirmishes and battles in Tennessee, North Carolina, West Virginia, Virginia, and as far north

as Maryland, and would surrender at Waynesville, North Carolina, on May 9, 1865. Legions were rare and few rose to prominence,

such as Phillip's Georgia Legion, Wade Hampton's Legion of South Carolina, and William Thomas' Legion of the Old North State.

| History of the Thomas Legion. |

|

| Thomas' Legion of Indians and Highlanders. |

|

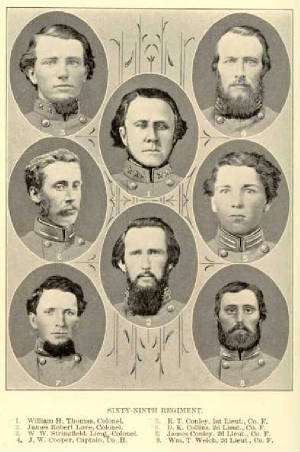

| Selected officers of the Thomas Legion. |

|

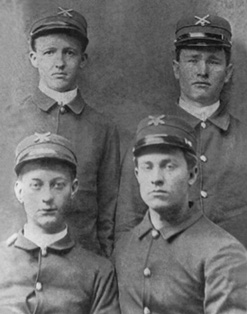

| Adams Brothers of Thomas' Legion. |

The infantry regiment was commanded by Colonel William Holland

Thomas, Lieutenant Colonel James R. Love II, and Major (Lieutenant Colonel from October 1864)

William Stringfield, and its cavalry battalion was under

the command of Lieutenant Colonels James A. McKamy (captured by Brigadier General George Custer in the Third Battle of Winchester)

and William C. Walker. During the conflict, this unit would also serve under various brigade

generals.

Col. William H. Thomas was the son of an Overmountain man who had fought the British at

Kings Mountain, and on his mother's side, he was cousin to President

Zachary Taylor. During the Civil War, he recruited both the Cherokee Battalion and Life Guard (Bodyguard) and was also present

at "The Last Shot" in Waynesville. Thomas would serve as Cherokee chief and Confederate colonel for the duration of the conflict,

and would die at the age of 88 in 1893. He remains the only white man to have ever served as a Cherokee chief.

Lt. Col. William C. Walker initially served in the 29th North Carolina Infantry before

joining the ranks of the Thomas Legion. While at home recovering in January 1864, he would be awakened and murdered by

outlaws.

Lt. Col. William W. Stringfield initially served as a private in the 1st (Carter's) Tennessee Cavalry

Regiment before becoming Captain of Company E, 39th (William M. Bradford's) Tenn. Regiment (aka 31st Tennessee

Infantry). He was elected as a member of the North Carolina Legislature in 1882-1883 and to the North Carolina Senate

in 1901 and 1905. Stringfield married Thomas' sister-in-law, Maria Love, and would live five years after the

First World War ended before dying of natural causes on March 6, 1923.

(Right)

The Adams Brothers of Cherokee (later Graham) County. Serving under Captain Willis Parker in Company I of the Thomas

Legion, Alfred and Benjamin (top) were first cousins to Aseph and John Posey (bottom). Courtesy grahamcounty.net.

Lt. Col. James R. Love

II initially served as a Captain

in the 16th North Carolina Regiment and fought bravely in the battles of Seven

Pines, Antietam, Seven Days Battles and Second Bull Run. He was wounded at Seven Pines and saw the Elephant in Virginia while serving under generals "Stonewall" Jackson and Robert E. Lee. Love was first cousin to Sallie Love, Thomas' wife, and was a graduate of Emory and Henry College, studied

law in Asheville, and served as a member of the North Carolina Legislature. After the

war, the former Confederate would serve as a member of the North Carolina Constitutional Convention in 1868 and

later in the state senate. Waynesville, a town that Love would often defend during the war, was founded by his

grandfather Robert Love. He would then move to Tennessee and increase his landholdings, and

while serving as a statesman, Love, aged 54, would die on November 10, 1885.

The Beginning

"A great majority of the people were poor and had no interest in slavery, present or prospective. But most of them had little mountain homes and, be it ever so humble, there is no place like home

— but when the Federal army occupied East Tennessee and threatened North Carolina..." Lt.

Col. William W. Stringfield, Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-'65,

Vol., 3, p. 734.

The

namesake Thomas' Legion was in honor of Cherokee chief, senator, and lawyer, William Thomas, who was 57 years

old when the unit officially organized. From the beginning of the Civil War, Thomas entreated

North Carolina Governors Henry Toole Clark and Zebulon Vance, even with President Jefferson Davis,

and various commanding generals that the mountaineers would be most effective as a locally employed guerrilla unit. These

highlanders were a unique blend of individuals possessing in-depth knowledge and understanding of their region. Because of

the lack of defenses, guerrillas reigned and unleashed terror on mountain communities for most

of the war with impunity. Eventually, Vance, Davis, Generals Martin, Bragg, Buckner, conceded that a force

such as the Thomas Legion would have been sufficient for defense of the region.

Its command was comprised of a diverse group of men

and although most had never served a single day in the military prior to the conflict, they brought a variety of skills and

leadership into the fray. The unit was formed of politicians, doctors, lawyers, scholars, students, Indians, farmers,

miners, merchants, laborers, hunters and trappers. They were local mountain men and Cherokee Indians and few were slave owners

or from renowned families, and in O.R., Series 1, 53, p. 314, Thomas said that the Cherokee didn't own any slaves. Though most of its members lacked financial status,

the legion would on a few occasions field some 2,500 soldiers, allowing a wide

range of skills and abilities to draw from. Some were descendants

of the famous Overmountain Men of the American Revolution, others being expert trappers and hunters, made fine scouts,

sharpshooters, geographers and topographers, and as politicians, lawyers, and scholars, there were strategists,

organizers and leaders, as miners, they became sappers, as Cherokee, they were loyal men and survivors of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and infamous Trail of Tears. Chief Yonaguska's warriors were well-known as prolific hunters, and according to John R.

Finger, The Eastern Band of Cherokees, 1819-1900, p. 62, in one year they provided their community with "540

deer, 78 bears, 18 wolves, and 2 panthers; the number of smaller mammals and birds killed

must have totaled thousands." (See also: Cherokee Indians: Weapons, War, and Warfare and Cherokee Indians: Weapons and Warfare.)

"The town was perfectly alive with people who had come to witness the departure of these brave volunteers. The

scene was one of thrilling interest and well calculated to melt the stoutest heart to sympathy and tears. The Buncombe Riflemen

are composed of first rate material and if they get into any engagement will reflect honor upon themselves and their native

section. They are pure metal, no mistake, and will contest every inch of ground with the enemy." Asheville [North Carolina] News, April 18, 1861.

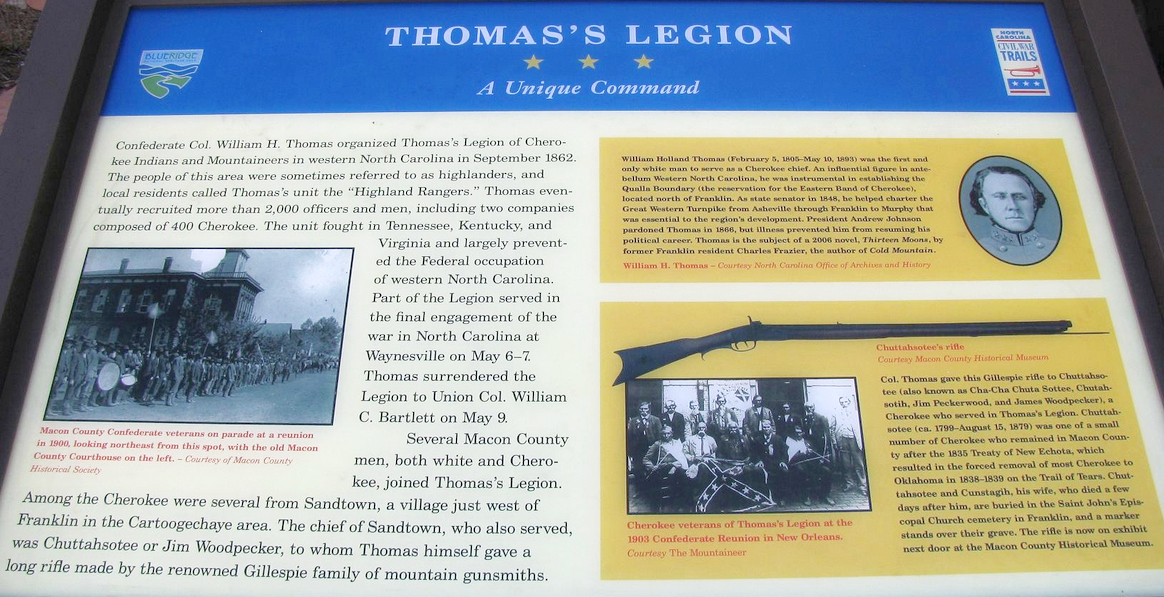

| Thomas Legion's Cherokee Veterans. |

|

| 1903 New Orleans Confederate Reunion. NPS. |

(About) The following caption appears under the original image: Above is

shown the last photograph ever taken of the remaining members of the famous Thomas Legion, composed of Cherokee Indians in

the Confederate Army. The photograph was made in New Orleans at the time of the New Orleans Reunion of Confederate Veterans.

The inscription on the banner in the photo is as follows: Cherokee Veteran Indians of Thomas Legion. 69 N. C. Regiment.

Suo-Noo-Kee Camp U. C. V. 4th Brigade, N. C. Division. Reading from left to right, those in the picture are: front row, 1

Young Deer; 2 unidentified; 3 Pheasant; 4 Chief David Reed; 5 Sevier Skitty; back row, 1 the Rev. Bird Saloneta; 2 Dickey

Driver; 3 Lieut. Col. W. W. Stringfield of Waynesville; 4 Lieutenant Suatie Owl; 5 Jim Keg; 6 Wesley Crow; 7 unidentified;

8 Lieutenant Calvin Cagle. All of these men are now dead with the exception of Sevier Skitty, who lives one mile from Cherokee.

Lieut. Col. Stringfield and Lieut. Cagle were white officers of the legion. Names of the men in the photograph were furnished

by James R. Thomas of Waynesville, son of the late Col. W. H. Thomas, who commanded the Thomas Legion. This band of Indians

built the first road across the Great Smoky Mountains.

"[A]n Indian [from Thomas' Legion] always executes an order

with religious fidelity. They scrupulously respect private property—there are no reports of depredations where they

are encamped. They are the best scouts in the world." Knoxville Register, February 21, 1863.

On

September 19, 1861, Davis believed that the Cherokee should be used to defend the "coast and swamps of North Carolina" (O.R. Series 1, 51, 2, p. 304) but, believing

that the disease infested swamps would spell certain death of Indians who had never ventured beyond the scope of the mountains,

Thomas presented a more practical strategy to which Davis would agree. The

coastal area would also be the first of the state's three regions to capitulate, which allowed longer imprisonment and

greater exposure to the numerous diseases at the POW Camps. The greatest threat to the Cherokee, nonetheless, would have been

immediate exposure to the infested swamps.

Thomas,

who was in his mid-50s, had amassed a lifetime of experiences prior to the

war, and he demonstrated a rare ability by earning the respect and loyalty of both Cherokee and Western North Carolinian. As

a boy, Thomas was adopted by the Cherokee, and he later defended their rightful claims as an Indian agent before

becoming Chief of the Eastern Band. He also acquired the trust and confidence of his fellow mountaineers by

serving in the North Carolina Senate, and as a self-taught

lawyer, he was able to persuade Washington to exempt some 1000 Cherokee from the Trail of Tears.

Thomas was in Washington during the Treaty of New Echota negotiations and had successfully lobbied for the right for a number of Indians to remain in North Carolina. These

Indians are the present-day Eastern Band, and they were also referred to as Oconaluftee, Lufty and Qualla Indians. In the late winter of 1839, while Thomas was in

Washington, Chief Yonaguska died. Thomas learned about it in April. Before his death, however, the old chief had summoned

the men in his band to form a circle around his pallet in the Soco Council House. They accepted his recommendation that "Little

Will" be allowed to succeed him. Yonaguska then advised them to abstain from drinking liquor and to never move west.

Thomas had become Chief of the Oconaluftee and he was the only white man to hold

that office. (See also Cherokee War Rituals, Culture, Festivals, Government, and Beliefs.)

The Western North Carolinians had fought the Cherokee for decades, so if they decide to fight

in the American Civil War will they join the North? Will they remain neutral? On the other hand, the Cherokee

had entered into six separate treaties with the United States between 1777 and 1835. In each case, federal authorities had

sought to extend the frontiers of white settlement by extinguishing Indian title to land.

The

U.S. had broken several

promises, including

President Andrew Jackson's unconscionable betrayal of Chief Junaluska and his Cherokee. The great warrior and chief had saved General Jackson's life

at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, but when "Old Hickory" was elected the 7th President, he would eagerly force

the Cherokee from their homeland. By the 1860s, however, the highlanders and Cherokee were neighbors and friends, and intermarriage

with neighboring whites was common. Prior to his death, Yonaguska had commanded his people to obey Thomas as his successor

as newly appointed chief. In 1883, Ziegler recorded that "before Yonaguska died he assembled his people and publicly willed

the chieftainship to his clerk, friend and adopted son, W. H. Thomas, who he commended as worthy of respect and whom he adjured

them to obey as they had obeyed him. He was going to the home provided for him by the Great Spirit; he would always keep watch

over his people and would be grieved to see any of them disobey the new chief he had chosen to rule over them."

Enforcing

Jackson's Indian removal policy, General Winfield Scott moved the Cherokee during the Trail of Tears, which resulted

in 4,000 dead Indians. The Cherokee still refer to the Trail of Tears as Nunahi-Duna-Dlo-Hilu-I

or Trail Where They Cried. It was on this perilous trail that Principal Chief

of the Cherokee Nation, John Ross, had lost his wife Quatie. (See also Cherokee Declaration and the American Civil War and American Indians in the Civil War.) Scott was a veteran of the War of 1812, hero of the Mexican-American War, former presidential candidate, and when in hostilities began in 1861, the aged hero was appointed General-in-Chief

of the Union Army. He was credited with Anaconda Plan, a strategy designed to quickly end the conflict. Other notable soldiers

of the Mexican War included Robert E. Lee, Braxton Bragg, U.S. Grant, "Stonewall" Jackson, Zachary Taylor, and Jefferson Davis.

On

September 15, 1861, two Cherokee companies, 200 soldiers, answered the call to

arms. These 200 Indians were originally known as the Junaluska Zouaves —

in honor of Chief Junaluska — and Thomas also referred to them as the North Carolina Cherokee Battalion. (Cherokee

Battalion, O.R., Series 1, 51, II, p. 304, and O.R., 1, 49, Part 2, p. 754). By

the end of the war, muster records contained the names of almost every able-bodied Cherokee, about 400 soldiers,

from North Carolina who had served in the Confederate Army. Their loyalty was to Chief Thomas

and then to the Confederacy. And according to O.R., 1, 53, p. 314 and census records of the time, slavery wasn't an issue for Cherokee

serving in the army.

According to Neely, North Carolina's Eastern Band

of Cherokees, p. 162, "Some Cherokees desired neutrality while as many as 30 joined the Union Army," but oral history states that many of the disloyal Indians were

later murdered by their relatives because they had betrayed Thomas. The Cherokee who had joined the Union Army not only fought against their brothers,

but after the War were credited for returning to the mountains with the dreaded smallpox. Captured Confederate Cherokee, however, had been held in Federal prison

camps, and after the conflict, the paroled Indians returned to the mountains and possibly as carriers of smallpox. The highly lethal disease is presently

considered biological warfare and even a Weapon of Mass Destruction. But it was mumps and measles that were

responsible for most of the Cherokee fatalities during the war, and subsequently smallpox killed

more than one hundred of the Indians. (See Thomas' letter concerning smallpox.)

President Jefferson Davis' Cousin and Friend

"North Carolina cannot remain much longer stationary; she must write her destiny either under

the flag of Mr. Lincoln and aid to coerce the south or unite with the south to resist and defend their rights." William Holland Thomas to his wife, January 1, 1861. John

C. Inscoe, The Heart of Confederate Appalachia: Western North Carolina in the Civil War.

Jefferson Davis, future President of the Confederacy, had married the young Sarah Knox Taylor,

the daughter of President Zachary Taylor and cousin to William Thomas, but although she would pass away just three months

later from malaria, it would serve to establish a bond between Davis and Thomas, one that would benefit the colonel during

the war. When Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, commander

of the Departments of East Tennessee and Western North Carolina, for instance, opposed allowing the aged colonel

the latitude of operating his legion as an independent command early in the Civil War, Thomas merely consulted with President

Davis, who then countermanded Smith's order. During the 1840s, Thomas would often visit then Congressman Davis during

his many visits to Washington while lobbying for the Eastern Cherokee and their right to remain in their ancestral

land.

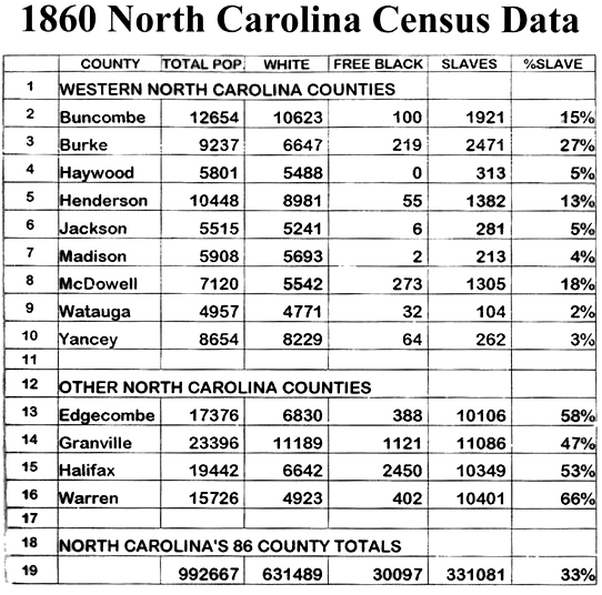

| 1860 US Census for North Carolina Counties. |

|

| 1860 US Census for North Carolina. |

| The Thomas Legion |

|

| The Thomas Legion Historical Marker. |

Thomas' American Civil War Strategy

Thomas believed in defensive guerrilla warfare and, since the Union army typically outnumbered the Confederate army by more than two-to-one, he

wisely opposed the traditional Napoleonic Tactics. The commander

was not a Fire-Eater, he initially opposed secession, and during the war a $5,000 bounty was offered to "anyone that would assassinate the Confederate Chief."

For most of

the Civil War, the Confederate Eastern Cherokee were equipped with the .69 caliber musket, which could only kill at a short

distance (50-100 yards) compared to the Union soldier’s Enfield (200-300 yards). It was obvious, the Union soldier had

a superior advantage, unless the Cherokee, without being detected, could shorten the distance. And guerrilla warfare allowed

the Cherokee to meet this objective. (See: Civil War Small Arms, Cherokee Indians: Weapons and Warfare, and The American Civil War and Guerrilla Warfare.)

"Many of them [Thomas' Legion] joined with the promise that they were not to be taken

out of the State except in the North Carolina mountain of defense." Captain Robert A. Akin, Company H, Walker's Battalion,

Thomas' Legion.

The mountaineers,

like their Overmountain forefathers of the Revolution, believed in a defensive yet guerrilla strategy.

Their mountain ancestors had proved their defensive strategy by surprising and destroying the British Army at Kings Mountain and

Cowpens. Who knew the Western North Carolina terrain better

than the indigenous Cherokee and Mountaineer? As the nation was entering into war, Thomas petitioned Richmond

to authorize the recruitment of "additional Indians and such whites as I may select." His primary goal was to recruit

a full battalion and ultimately a mounted regiment to operate as an independent guerrilla unit for the "local defense

of the Cumberland Gap in pro-Unionist East Tennessee and Western North Carolina." According to Thomas' writings, Jefferson Davis agreed to arm, supply, and support the unit.

In future correspondence with Davis,

Thomas stated, "I have increased the Battalion of Indians and Mountaineers to a regiment and am progressing with a Legion.

Not for one year but for three years or during the war." (North Carolina Division

of Archives and History, April 17, 1862; and Vernon H. Crow, Storm in the Mountains: Thomas' Confederate Legion of

Cherokee Indians and Mountaineers, 12-36.) Thomas also wrote to Davis and "submitted a plan for the defenses of East Tennessee." November 8, 1862, Strawberry Pains, TN. (O.R., Ser. I, Vol. 20, pt. II, p. 395.)

General Ulysses S. Grant, while traveling through

the Cumberland Gap in 1864, noted that "with two brigades of the Army of the Cumberland I could hold that pass against

the army which Napoleon led to Moscow."

Roman Emperor Hadrian and the world’s greatest military power

were dealt crippling blows by guerrilla bands in the early second century. Because of Rome’s losses to guerrilla raids from the north, it succumbed to a stalemate

and constructed a massive wall, known as Hadrian's

Wall, to separate the Roman Empire from northern Britain -- presently referred to as the Scottish Highlands. The Roman footprint never

stepped beyond northern Britain, and Hadrian's Wall was

a great guerrilla victory. Applying their familiar terrain and home field advantage,

King Leonidas and his 300 Spartans, with Greek allies, defended the Pass of Thermopylae and inflicted as many as 20,000

casualties on the invading Persian Army. Prior to surrendering the Army of Northern

Virginia, Gen. Lee seriously contemplated disbanding the army, creating a massive guerrilla force, and relocating it

to the mountains. And in more recent history, the Vietnamese excelled in guerrilla warfare and proved to be a formidable

foe.

Thomas had earlier petitioned North Carolina Governors Clark and Vance, Davis, and Bragg to employ the Thomas Legion "to defend

the passes of the Smokies," and in February 1864, he reminded South Carolina officials that in the beginning of the war he

had urged the Carolinas to make preparations to defend the passes in the Smoky Mountains for their common protection, and

by authority of President Davis, he had raised a legion of Indians and highlanders. (O.R., Series 1, 53, p. 313.) Although Richmond honored the request by sending Thomas and his Cherokee Battalion to the Smokies, in May 1864 it pushed the infantry regiment of the legion into

the Shenandoah Valley. On May 2, 1864, in a letter to

Headquarters

Armies Confederate States, a concerned Bragg said that "General Longstreet’s army having left East Tennessee opened

all of Western North Carolina, Northeastern Georgia, Northwestern South Carolina, to incursions of the enemy." On the

same date, Colonel Black, First South Carolina

Cavalry, stated that although Thomas and the Cherokee were assigned to the mountains, a wide gap remains an open invitation for

the enemy. (O.R. Series 1, 53, p. 333.)

Both Bragg

and Black had voiced the region's deplorable state during the month that the regiment, Thomas' Legion, was

ordered to the Shenandoah Valley. But exigencies of war had moved most of the Department of East Tennessee

and the Western District of North Carolina into the valley and attached it to the newly formed Army of the Valley under

the command of Gen. Jubal Early in an attempt to draw as much of Grant's army away from Lee in Virginia. Remaining in the

mountains was a skeleton force that would in no wise be capable of defending such a large parcel of real estate. Bushwhackers

were now lords of the land and they plundered East Tennessee and

Western North Carolina with little to no resistance. One incident, the Shelton Laurel Massacre, cast a dark shadow over the region, and such lawlessness and mountain madness contributed to the desertions of the

Thomas Legion, as well as other units, as men returned home in hopes of protecting their families. There are many references

to the area's deplorable conditions during this time. See O.R. Series IV, 2, 732, O.R., 53, 324, O.R., Series 1, Vol. 32, pt. II, pp. 610-611, O.R., 1, 53, pp. 331-335, and Jefferson Davis' Letter of Confidence in Thomas' Legion - January

4, 1865.

While Thomas and the Cherokee Battalion were assigned to Western North Carolina, the

diplomatic colonel persuaded and recruited dozens of Confederate deserters to the Thomas Legion and together they

fought the enemy, but his actions resulted in a court-martial, yet similar to other court-martials that the former senator

received, Davis merely overturned it.

Thomas, who would be 60 years young in 1865, was

an experienced leader, hands on manager, capable planner, and skillful organizer, but many of his proposals to Richmond

fell upon apathetic ears. He voiced his opposition to the Confederate draft, known as the Conscription Act of April

1862, and stated that it would "force the pro-Unionist, tory, and

abolitionist to flee," meaning it would cause desertion on a broad scale — and it did. Thomas presented an alternative

that would allow the citizens to be used as Home Guard and in non-combatant roles such as sappers, laborers, and

miners. The Cherokee chief requested that all

slaves should be emancipated and employed as engineers and laborers — but of course the idea was rejected.

He

desired to allocate the highlanders strictly as a local defense force, since they were the most

familiar with the area, but another rejection was in order. Southern Appalachia would become host to bushwhackers, bands of deserters, and escaped Union prisoners that would collectively

unleash and create a swath of carnage as saboteurs and insurgents of the 19th century.

In 1864, Thomas proposed a blanket amnesty bill to Headquarters of the Confederate States

in a broad attempt to bring calm to an already ravaged region by pardoning all deserters, abolitionists, outliers, and pro-Unionists in hopes that a good portion of these fighters would then be employed as Home Guard in

the North Carolina mountains that they had recently swept with terror. His amnesty solution, like the greater majority of all

his requests to Richmond, failed to materialize, so war crimes would continue until the war ended. In May 1865, one month after Lee had surrendered to Grant, Thomas was in White Sulphur Springs (present-day Waynesville), and without interference from headquarters on this occasion, he

would surrender on his own terms, and it would include deception in textbook fashion that would have made Sun Tzu proud in

The Art of War, when he said that "all warfare is based on deception." The Rebel chief would first utilize every available

Cherokee to commit bluffs of epic proportion, meaning psychological operations

and warfare,

before he brilliantly captured the Southern city that

had only recently surrendered to the Union force now occupying it. See also Cherokee War Rituals.

| Map of Civil War railroads. |

|

| The Thomas Legion spent much of the war defending the sole railroad in East Tennessee. |

Guns and Gear

The

Thomas Legion's soldiers were initially armed with outdated "dusty flintlocks" and "bored-out squirrel rifles." Later, its

soldiers were equipped with captured modern Enfield Rifles.

"The

mountains are pouring forth their brave sons in great numbers." Raleigh Register, July 9, 1861.

In September 1862, Thomas

was appointed Colonel of the Legion, and the unit would soon field some 2,500 officers and men, formed in infantry,

cavalry, and a light artillery battery. The organization was a Roman Legion styled unit operating under one command.

Though originally formed to protect the Cumberland Gap and Western North Carolina landscape, the unit was involved in

many battles throughout the South. The legion defended the vital and strategic Saltworks and railroads (O.R., Ser. 1, Vol. 16, pt. II, p. 716) and was instrumental in constructing and maintaining the Cumberland Gap supply lines, and in 1864 a fragment of the unit moved into the Shenandoah Valley where it engaged the likes of Sheridan

and Custer. The Confederate supply routes were constructed by the legion in the Great Smoky Mountains during the harsh

winter of 1862, with the main objective to connect with the Confederate forces in East Tennessee. The force also guarded the

Cumberland Gap, fought the Union army, practiced countless hours of drills, and

fought bands of outlaws, deserters, and

bushwhackers — which generally operated as saboteurs. Engaging and fighting bushwhackers was contrary to fighting

an organized army in lines of battle, where Union and Confederate armies applied Napoleonic Tactics and marched

into battle, squared the opponent, and attrition generally determined the victor. But bushwhackers were masters of the

ambush with deception and swift attacks applied to their advantage. The ambush tactics of the many elusive units

hiding behind trees and in ravines, enabled them to inflict costly losses on an enemy and then vacate the brush

quickly.

"I have it from the lips of

some Union leaders that the Federal forces intend to sack Asheville, as soon as they can possibly get there. They actually

hate Asheville with a perfect hatred." Lt. W. F. Parker while stationed near Knoxville. [Parker was a Confederate

soldier from Buncombe County.] Asheville News, February 27, 1862.

To: Governor Zebulon

B. Vance

Knoxville

Nov. 22, 1862

One consideration now animates us all. What will ensure

success not what would be most agreeable to us. The Legislature appropriated two millions of dollars to defend Eastern

North Carolina and the Western frontiers? Both are now in danger. The western Counties are in danger of being over run by

deserters and renegades who by the hundred are taking shelter in the smoky mountains. The men between 35 and 40 west of the

Blue Ridge should be furnished with arms and ammunition, and required to aid in guarding their homes and the Confederate should

be required to place Military compys at every trap in the Smoky mountains from Ashe to Cherokee. As long as we can hold the

Country encircled by the Blue Ridge and Cumberland mountains and their outside slopes we have the heart of the south, which

commands the surrounding Plains. The loss of this country larger than England or France is the loss of the Southern Confederacy

and we sink under a despotism. W. H. Thomas. Christopher M. Watford, The Civil War in North Carolina: Soldiers' and Civilians'

Letters and Diaries, 1861-1865. Volume 2: The Mountains, 79.

Gov. Zebulon B. Vance to James A. Seddon, Secretary

of War, C.S.A., January 5, 1863

The enforcement of the Conscript law in East Tennessee

has filled the mountains with disaffected desperadoes of the worst character, who joining with the deserters from our Army

form very formidable bands of outlaws, who hide in the fastness, waylay the passes, rob, steal, and destroy as pleased. The evil has become so great that travel has almost been suspended through the mountains.

John C. Inscoe, The Heart of Confederate Appalachia, Western North Carolina in the Civil War, 114.

Notes:

A skirmish is considered a brisk or minor encounter between small bodies of troops, especially advanced or outlying detachments

of opposing armies. Example: There were several skirmishes prior to the Battle of Gettysburg.

A battle or engagement is a prolonged and general conflict pursued to a definite decision between large, organized armed

forces. Example: Battle of Gettysburg.

An action can be a battle or a skirmish. Example: There were several actions during the Gettysburg Campaign.

The term military campaign applies to large scale, long duration, significant military strategy plan incorporating a series

of inter-related military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war.

...continue

to 1861-1863 (Skirmishes

and Battles)

...continue to 1864-1865 (Skirmishes and Battles)

Recommended Reading: Storm in the Mountains: Thomas' Confederate

Legion of Cherokee Indians and Mountaineers (Thomas' Legion: The Sixty-ninth North Carolina Regiment). Description:

Vernon H. Crow, Storm in the Mountains, dedicated an unprecedented 10

years of his life to this first yet detailed history of the Thomas Legion. But it must be said that this priceless addition has

placed into our hands the rich story of an otherwise forgotten era of the Eastern Cherokee Indians and the mountain men of

both East Tennessee and western North Carolina who would fill the ranks of the Thomas Legion during the four year Civil

War. Crow sought

out every available primary and secondary source by traveling to several states and visiting from ancestors of the

Thomas Legion to special collections, libraries, universities, museums, including the Museum of the Cherokee, to

various state archives and a host of other locales for any material on the unit in order to preserve and present

the most accurate and thorough record of the legion. Crow, during his exhaustive fact-finding, was granted access

to rare manuscripts, special collections, privately held diaries, and never before seen nor published photos and

facts of this only legion from North Carolina. Crow remains absent from the text as he gives a readable account

of each unit within the legion's organization, and he includes a full-length roster detailing each of the men who served in

its ranks, including dates of service to some interesting lesser known facts.

Storm in the Mountains, Thomas' Confederate Legion of Cherokee Indians and

Mountaineers is presented in a readable manner that is attractive to any student and reader of American history, Civil

War, North Carolina studies, Cherokee Indians, ideologies and sectionalism, and I would be remiss without including the

lay and professional genealogist since the work contains facts from ancestors, including grandchildren, some of which

Crow spent days and overnights with, that further complement the legion's roster with the many names,

dates, commendations, transfers, battle reports, with those wounded, captured, and killed, to lesser yet interesting

facts for some of the men. Crow was motivated with the desire to preserve history

that had long since been overlooked and forgotten and by each passing decade it only sank deeper into the annals of obscurity.

Crow had spent and dedicated a 10 year span of his life to full-time research

of the Thomas Legion, and this fine work discusses much more than the unit's formation, its Cherokee

Indians, fighting history, and staff member narratives, including the legion's commander, Cherokee chief and Confederate

colonel, William Holland Thomas. Numerous maps and photos also allow the

reader to better understand and relate to the subjects. Storm

in the Mountains, Thomas' Confederate Legion of Cherokee Indians and Mountaineers is highly commended, absolutely

recommended, and to think that over the span of a decade Crow, for us, would meticulously research the unit and

present the most factual and precise story of the men, the soldiers who formed, served, and died in the famed Thomas

Legion.

Recommended Reading: North Carolina Troops, 1861-1865: A Roster

(Volume XVI: Thomas's Legion) (Hardcover) (537 pages), North Carolina Office of Archives and History (June 26, 2008).

Description: The volume begins with an authoritative 246-page history of Thomas's Legion. The history, including Civil War

battles and campaigns, is followed by a complete roster and service records of the field officers, staff, and troops

that served in the legion. A thorough index completes the volume. Continued below.

Volume XVI

of North Carolina Troops: A Roster contains the history and roster of the most unusual North Carolina Confederate Civil

War unit, significant because of the large number of Cherokee Indians who served in its ranks. Thomas's Legion was the creation

of William Holland Thomas, an influential businessman, state legislator, and Cherokee chief. He initially raised a small

battalion of Cherokees in April 1862, and gradually expanded his command with companies of white soldiers raised in western

North Carolina,

eastern Tennessee, and Virginia.

By the end of 1862, Thomas's Legion comprised an infantry regiment and a battalion of infantry and cavalry. An artillery battery

was added in April 1863. Furthermore, in General Early's Army of the Valley, the Thomas Legion was well-known for its fighting

prowess. It is also known for its pivotal role in the last Civil War battle east of the Mississippi

River. The Thomas Legion mustered more than 2,500 soldiers and it closely resembled a brigade. With troop roster, muster records, and Compiled Military Service Records (CMSR) this volume

is also a must have for anyone interested in genealogy and researching Civil War ancestors. Simply stated, it is an outstanding

source for genealogists.

|