|

| Cherokee History, Culture, and Heritage |

|

| Cherokee Indian History and Heritage |

(Right) Map showing lands the Cherokee inhabited at their height. Cherokee Indians believed that all land

belonged to the Great Father and that they were to be caretakers of it.

It's always been my belief that we were put here in the beginning.

This is our land. This is where our Creator wanted us to be, because this is where he put us. All the things here have helped

us survive—the natural resources, the plants. That's how we have lived; without those things we wouldn't be here. He's

blessed us with this land, and in return we should respect it, we should take care of it. —Marie Junaluska

The Cherokees say that they have always been here in the southern mountains,

that the Creator put them here. The first man and first woman, Kanati and Selu, lived at Shining Rock Wilderness, near present-day

Waynesville, and the first Cherokee village was at the Kituhwa Mound, near present-day Bryson City. They say that their language

and their traditions were given to them by the Creator.

Many contemporary Cherokee people believe, as Christians, in the creation

story in Genesis. Walker Calhoun said, "When Adam and Eve was without a garden, the Creator told them to fill the earth with

people. And God told Adam to take care of the earth."

Many Cherokee people also believe that the Creator placed them here in the

mountains (see North Carolina Mountains), and they continue to tell Cherokee creation stories. They tell how the water beetle, Dayunishi, brought mud from below

the waters to make the earth, and how the great buzzard shaped that earth with his wings, making the mountains of Cherokee

country.

Archaeological evidence shows people living in the southern Appalachians more

than eleven thousand years ago; we know them through their distinctive stone tools and their beautifully made, fluted spear

points. During this time, at the end of the last Ice Age, the climate was colder, the southern Appalachians were covered with

spruce and fir, and mastodons and other extinct species foraged the upland landscape. Even today, Cherokee stories tell of

strange, giant animals that once roamed the mountains, hearkening back to the end of the Ice Age. Cherokee elder Jerry Wolfe

recalls, "My dad always said that when the Cherokees came into this country, into these mountains, that it was dangerous.

It was a dangerous place because of all the monsters that lived here."

About ten thousand years ago, the climate grew warmer, and people adapted

to a changing environment by developing new tools and new, more diverse patterns for hunting, fishing, and gathering plant

foods. Archaeological sites yield different and distinctive styles of spear and dart points, and weights and sinkers for fishing

nets as well as fishhooks carved from bone. People carved stone bowls from steatite (soapstone), and created mortars and pestles

for grinding seeds and nuts, some of which were cultivated. People began making baskets at least ninety-five hundred years

ago, and their woven, twined cords left impressions on clay hearths that survived the ages. An extensive network of trading

paths followed rivers and mountain ridges.

Over the millennia, people in the southern mountains developed villages, agriculture,

pottery, bows and arrows, and more elaborately carved stone pipes. According to scholars, Cherokee language, part of the Iroquoian

language family, became a separate, distinct language at least thirty-five hundred years ago (1500 B.C.).

More than a thousand years ago, people in the southern mountains began developing

a distinctively Cherokee way of life, with patterns of belief and material culture that survive to this day. They began to

focus on growing corn, whose name reflects its importance: selu, name of the first Cherokee woman. They built permanent, well-organized

villages in the midst of extensive cornfields and gardens throughout the fertile river valleys of the Cherokee country. In

these villages, homes ranged around a central plaza used for dances, games, and ceremonies. At one end of the plaza, the council

house, or townhouse, held the sacred fire, symbol of the Creator and embodiment of the spirit of the town. Often the townhouse

stood on an earthen mound, which grew with successive, ceremonial rebuildings.

At the heart of this culture was the idea of balance, or duyuktv, "the right

way." Men's hunting and fishing, for example, was balanced by women's farming. The rights of the individual were balanced

with the good of the whole, resulting in great personal freedom within the context of responsibility to the family, clan,

and tribe. The size of the townhouse reflected the size of the village because all the people of the village—men, women,

children, and old people—had to fit in the townhouse in order to make decisions together. On an individual level, the

physical, intellectual, and spiritual aspects of oneself were to be integrated and balanced. Thus one became a "real person,":

Ani-Yvwiya.

Every aspect of daily life and the physical

world had spiritual significance. Ceremonies and customs maintained balance for the individual and the community. Men fasted and

prayed before hunting, and then offered thanks in a ceremony after killing an animal; on returning to their village,

they shared the meat, used all parts of the animal, and often danced to honor the animal. When gathering plants, only the

fourth was taken, and a gift was left in return. Even today stories of the Little People emphasize the importance of reciprocity.

Their permission must be asked before picking up anything from the woods—a stone, a feather, a leaf—and if their

permission is given, a gift must be left. Entire villages fasted and purified themselves in order to give thanks before eating

the new corn crop. Every day began with the going-to-water ceremony, when everyone entered a stream near their village, faced

east, and prayed to the seven directions: the four cardinal points, the sky, the earth, and the center—the spirit. They

gave thanks for a new day, and washed away any feelings that might separate them from their neighbors or from the Creator,

emerging cleansed physically, mentally, and spiritually.

| Cherokee History and Heritage |

|

| Cherokee Indian lands today were carved from the original lands |

Cherokees developed and cultivated corn, beans, and squash—"the three

sisters"—along with sunflowers and other crops. In addition to farming, Cherokee women continued gathering wild foods

from woods and fallow fields: nuts, wild greens, fruit, and berries. Men continued hunting wild game and fishing.

Cherokee women owned their houses and fields, and passed them from mother

to daughter. Cherokee women also passed their clan affiliation to their children, both male and female. A man's most important

relatives were his mother, maternal grandmother, and his sisters—the women of his clan. Until he married, he lived in

their houses, and when he married he moved to his wife's house. People of the same clan did not marry each other. The clans

also enforced unwritten laws regarding homicide and other social infractions. If someone was killed, his or her clan was owed

a life from the clan of the killer. When this life was paid, balance was restored, and no further retribution took place.

Clan members sat together at dances and ceremonies, in special sections reserved for their clan. Although oral tradition

suggests that at one time there may have been as many as fourteen clans, each with its own special skills and responsibilities,

today seven Cherokee clans survive: wolf, deer, bird, paint, long hair, wild potato, and blue.

The existence of gorgets carved from marine shells from the Gulf of

Mexico suggests the extent of Cherokee trading practices. Worn around the neck, these round shell ornaments, about four inches

in diameter, were elaborately carved with spirals, crosses, rattlesnakes, water spiders, and birds. Many of these creatures

play an important role in Cherokee stories. Cherokees also traded mica throughout eastern North America, and received

copper and pipestone from the Great Lakes region and plants and shells from the Atlantic coast.

Chunkey stones, marbles, and ball sticks indicate favorite games of the time.

Smooth chunkey yards were found in villages. Stickball games were played on large cleared fields.

Archaeological evidence, early written accounts, and the oral history

of the Cherokee themselves show Cherokees as a mighty nation controlling more than 140,000

square miles with a population of at least thirty-six thousand (see History of the Cherokee). Unified by language, traditions, and its clan system, the Cherokee nation

had no centralized government or written laws. Towns governed themselves by democratic consensus, and each had its

own priest, war chief, and peace chief. Cherokee people were athletic, with some men as much as six feet tall. Everything

they needed they created from their environment: food, medicine, clothing, shelter, weapons, musical instruments, jewelry,

and goods for trade. They practiced empirical science by observing the world around them, and then they used that knowledge

combined with spiritual inspiration and practical application to create a society that used resources in a sustainable way.

Into this ever-changing but ever-balancing world came people from Europe

and Africa. In 1540, Hernando de Soto's expedition passed through the margins of Cherokee territory. Their gifts, their diseases,

and their greed foreshadowed the patterns of the next three hundred years of Cherokee history. In search of gold and slaves,

this army of "500 Christians," as they described themselves, executed any who would not provide them directions to the next

settlement. Strangers without accurate maps or sufficient food, they raped, murdered, and demanded tribute as they crossed

through the rugged mountains. According to the Spanish chroniclers on the expedition, Cherokee villages provided food: seven

hundred turkeys from one village; twenty baskets of mulberries from another; and three hundred hairless dogs—supposedly

a delicacy. The Cherokees, however, say that this was a joke. They say they gave the Spaniards opossums, which Cherokees do

not eat because of its scavenging habits. De Soto's chroniclers commented on the impressive weaponry of American Indians,

noting that the Spanish men did not have the strength to pull their bows. Cherokee warriors could fire six or seven arrows

in the time it took to load and fire one arquebus, the unreliable Spanish flintlock. Their arrows

had enough power to entirely penetrate the body of a horse from hindquarters to heart. (Cherokee weapons and warfare.) Chroniclers also marveled at the abundant game, wild foods, and cultivated

crops among Native Americans of the Southeast. They, and a later expedition led

by Juan Pardo in 1567, traded beads, knives, buttons, and other goods for food. Some African slaves escaped these expeditions and continued to live with Native tribes.

The Spaniards also brought devastating diseases. Like other Native Americans,

the Cherokee people had no resistance to European diseases, which quickly became epidemic. Because diseases traveled ahead

of de Soto's expedition, the Spaniards found some villages deserted, their entire population dead. Some scholars now estimate

that 95 percent of Native Americans were killed by European diseases within a hundred

and fifty years of Columbus's landing, thus enabling conquest and giving the appearance of an empty land. (North Carolina Census Records.)

After these first expeditions,

with their brief contact, the Cherokees had only sporadic exposure to Europeans. They met the British in Virginia in 1634.

By 1650, they had begun growing peaches and watermelons, acquired through trade. But it wasn't until the 1690s that the

Cherokees began making regular contact with any Europeans. In 1693, Cherokee leaders traveled to Charlestown to complain that

Cherokee people were being sold as slaves to the British, a practice that continued for thirty years after their meeting.

In the eighteenth century, the Cherokees felt the full impact of Europeans

in their territory. Peaceful cultural exchange, trade goods, new technology, intermarriage between Cherokee women and British

traders, and trips to England by Cherokee leaders were the positive results. Negative results included three major smallpox

epidemics, each killing one-third to one-half of the Cherokee population at the time; repeated "scorched earth" military campaigns

destroying dozens of Cherokee towns; and the loss of 75 percent of the Cherokee territory through treaties. The Cherokees

began the century living in towns built around mounds, celebrating festivals, sharing wealth, and balancing men's and women's

roles. By the end of the century, many of the old towns had been destroyed or ceded, and the federal government was pressing

a Civilization Policy to make Cherokee men farmers instead of hunters and warriors, and to make women spinners and weavers

rather than the successful farmers they had been.

The Cherokees began the 1700s far outnumbering the colonists, even though

their population had been drastically reduced by epidemics. They ended the century vastly outnumbered, with colonists crowding

tribal lands. From an estimated population of thirty-five thousand in 1685, about seven thousand survived in the mid-1760s.

This population, still spread throughout the southern Appalachians, was concentrated in the Lower and Middle Towns (along

the Little Tennessee River), the Valley Towns (along the Hiwassee River), and the Overhill Towns (along the Tennessee River).

During this time, the Cherokees helped the colonists by eliminating the Yamassee

and Tuscarora, their neighbors and enemies, who had been the buffer between themselves and the Europeans. They also brought

deerskins for trade. From 1700 to 1715, nearly a million skins were shipped from Charlestown to Europe, and the trade increased

for more than fifty years. The trade brought white traders—mostly Scots—into Cherokee country; the traders often

married Cherokee women.

A Cherokee man might trade fifty deerskins in a good season, and according

to exchange rates set in 1716, these would buy a gun (35 deerskins), sixty bullets (2 deerskins), twenty-four flints (2 skins),

one steel for striking flint (1 skin), and perhaps an axe and hoe (5 deerskins each.) Cherokee women actively participated

in the trade, to the surprise of the British. The corn raised by Cherokee women, and their baskets, were in great demand,

and in turn they received cloth, iron pots, weapons, plows, hoes, and bells. Exchange rates set eighty-four bushels of corn

as the price of a calico petticoat.

During this period of trade, Cherokee men began hunting with guns as well

as continuing to use bows and arrows. The Cherokee began keeping and breeding horses about 1720, soon developing large herds.

Because traders used horses to carry their packs, the Cherokee word for trader was the same as the word for horse, sogwili.

Cherokee women, in addition to their already extensive agriculture and woodland

gathering, began growing apples (from Europe), black-eyed peas (from Africa), and sweet potatoes (from the Caribbean.) By

mid-century, they were keeping horses, chickens, and hogs. They resisted raising cattle because the slow nature of cattle,

they thought, would be imparted to anyone who ate beef, and because cattle were so destructive to gardens that they required

fencing. By the end of the century, however, Cherokee households included cows as well. Cherokee Beloved Woman Nancy Ward

said that she saved Lydia Bean, a white woman, from being burned at the stake because she knew how to make butter and cheese

and would teach the Cherokee women to do so.

Nancy Ward and other Cherokee women attended every treaty signing in the eighteenth

century. At first they asked where the white women were, but they soon learned that only white men made treaties. They continued

to send greetings to the queen and to white women in Europe, while the British ridiculed the Cherokee "petticoat government."

Peaceful trade and intermarriage went on from 1700 to 1760. From 1760 to 1794,

however, the Cherokees were at war. Events throughout this period gave rise to stories about Indians scalping settlers on

the frontier, stories that became part of the American myth of this country's origins, a myth since dramatized in novels,

Wild West shows, medicine shows, radio, and finally television and movies. These stories live on in the oral history of white

frontier families as well. In reality, Cherokee actions against settlers were either part of military action directed by the

British, or retaliation for murder according to Cherokee laws controlling homicide and its punishment through the clan system.

Historical documents further show that Cherokee violence against settlers was matched by the violence of individuals of European

descent and by their military forces. Both sides committed atrocities.

In the French and Indian War, the Cherokees allied themselves with their main

trading partners, the British; soon, however, the Cherokees turned against them. In 1759, Cherokee men on their way home from

aiding British forces and Virginia militia were killed in an ambush by Virginia colonists, German settlers from whom they

stole horses. The unwritten Cherokee law, universally enforced by clans throughout the Cherokee nation, required a life for

a life. If the murderer could not be found, then someone in his clan was executed in his place. The white people had maintained

that they were all of the same clan, so the remainder of the Cherokee war party, on the way home, killed nineteen German settlers

on the Yadkin River in North Carolina. From the Cherokee perspective, this ended the matter, but from the British and colonial

perspectives, the Cherokees had murdered innocent settlers. Colonists retaliated against Cherokee towns, and Cherokee warriors

retaliated further. The Virginians who had ambushed the Cherokees sold their scalps to the British and collected a bounty,

and that turned the Cherokees against their former allies.

Early the next year a delegation of Cherokee leaders went to Charlestown to

make peace. Cherokees still operated as a confederation of autonomous towns united by language, culture, and clan kinship,

so they sent a delegation of town chiefs. The governor refused to meet with them and sent them under armed guard to Fort Prince

George. There the peace delegation became hostages, and finally all twenty-two were killed in an uprising. As a result, in

February of 1760, Cherokees led by Oconostota, Ostenaco, and Willenawaw laid siege to the British garrison at Fort Loudoun,

in their Overhill Towns, next to the capital city of Echota. Ostenaco, angered by the treachery of the British, was quoted

in the South Carolina Gazette: "Make peace who would, I will never keep it."

In response, South Carolina mounted an expedition led by Colonel Archibald

Montgomery that burned and destroyed all the Cherokee Lower Towns in upper South Carolina. Cherokee forces stopped the army

at the town of Etchoe, which was on the Little Tennessee River (near present-day Otto, North Carolina), in June of 1760, and

they saved the Middle Towns. Montgomery's defeat meant that relief would not be coming to Fort Loudoun, and in August, troops

there surrendered, promising to give all their weaponry to the Cherokee. Before they left the fort, however, the soldiers

buried their powder and shot, and threw their guns and cannon into the river. In retaliation, the Cherokees attacked the departing

troops the next morning, killing one soldier for each Cherokee chief killed in South Carolina, and taking the rest prisoner.

Captain John Stuart, who was well liked by the Cherokees, was taken away by Attakullaculla, who delivered him safely to Virginia.

The following year, in 1761, Colonel James Grant, formerly a lieutenant with

Montgomery's expedition, mounted another campaign against the Cherokees. Again, the expedition devastated the Cherokee Lower

Towns. Once again the Cherokees, led by Oconostota, brought warriors to the narrow pass below the village of Etchoe. There

Grant and his troops fought for five hours against thousands of Cherokee warriors. Later Grant commented that if the Cherokees

had not run out of ammunition, they would have defeated the British.

Grant pushed through into the Little Tennessee River Valley, destroying fifteen

towns, more than fifteen hundred acres of crops, and killing livestock. His soldiers complained what hard work it was to cut

down the huge Cherokee orchards and to destroy the well-built houses. Perhaps the most poignant comment came from Lieutenant

Francis Marion, later the legendary "Swamp Fox" of the American Revolution.

| Cherokee Culture and History |

|

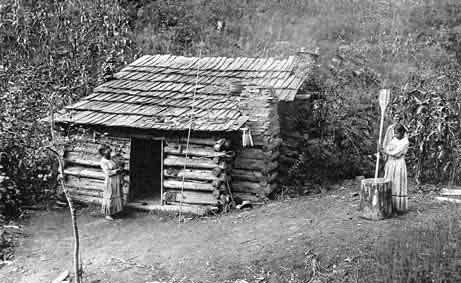

| Cherokee House in 1800s. Courtesy National Park Service |

We proceeded, by Colonel Grant's orders, to burn the Indian cabins.

Some of the men seemed to enjoy this cruel work, laughing heartily at the flames, but to me it appeared a shocking sight….But

when we came, according to our orders, to cut down the fields of corn, I could scarcely refrain from tears. Who, without grief,

could see the stately stalks with broad green leaves and tasseled shocks, the staff of life, sink under our swords with all

their precious load, to wither and rot untasted in their mourning fields.

I saw everywhere around the footsteps of the little Indian children, where

they had lately played under the shade of their rustling corn. When we are gone, thought I, they will return, and peeping

through the weeds with tearful eyes, will mark the ghastly ruin where they had so often played.

"Who did this?" they will ask their mothers, and the reply will be, "The white

people did it—the Christians did it!"

And thus, for cursed mammon's sake, the followers of Christ have sowed the

selfish tares of hate in the bosoms of even Pagan children. The

destruction of so many towns within two years worked a hardship on the Cherokees, who took to the woods and mountains, later

rebuilding some but not all of these towns. This destruction was humbling as well: for the first time, Cherokee country had

been successfully invaded by Europeans.

Following Grant's campaign of 1761, the Cherokees made peace with Great Britain.

Lieutenant Henry Timberlake volunteered to visit the Cherokees to assure both sides that the peace would be kept. He stayed

at Echota for three months. Then Timberlake took three Cherokee leaders—Ostenaco, Cunne Shote (Stalking Turkey), and

Woyi (Pigeon) to London where they met with King George III and exchanged presents. The Cherokees and other tribes heartily

approved of the king's Proclamation of 1763, which stated that colonists would not settle west of the Blue Ridge.

At the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in 1775, Richard Henderson, a land speculator

and Daniel Boone's employer, brought wagon loads of presents and whisky for the Cherokees in hopes of inducing them to sign

away their hunting grounds that occupied nearly all of the present-day state of Kentucky. The prophetic remarks of Dragging

Canoe, Cherokee warrior and cousin of Nancy Ward, were recorded:

Whole Indian nations have melted away like snowballs in the sun before

the white man's advance. They leave scarcely a name of our people except those wrongly recorded by their destroyers. Where

are the Delawares? They have been reduced to a mere shadow of their former greatness. We had hoped that the white men would

not be willing to travel beyond the mountains. Now that hope is gone. They have passed the mountains and have settled upon

Cherokee land. They wish to have that usurpation sanctioned by treaty. When that is gained, the same encroaching spirit will

lead them upon other land of the Cherokees. New cessions will be asked. Finally the whole country, which the Cherokees and

their fathers have so long occupied, will be demanded, and the remnant of Ani-Yvwiya, the Real People, once so great and formidable,

will be compelled to seek refuge in some distant wilderness. There they will be permitted to stay only a short while, until

they again behold the advancing banners of the same greedy host. Not being able to point out any further retreat for the miserable

Cherokees, the extinction of the whole race will be proclaimed. Should we not therefore run all risks, and incur all consequences,

rather than submit to further loss of our country? Such treaties may be all right for men who are too old to hunt or fight.

As for me, I have my young warriors about me. We will have our lands. I have spoken. The

Cherokees, along with many other tribes, allied with the British during the American Revolution. At British direction, the

Cherokees, often accompanied by Tories dressed as Indians, attacked border towns in present-day South Carolina, North Carolina,

Georgia, and Tennessee. A punitive American expedition in 1776 took forces under General Griffith Rutherford to attack Cherokee

villages far behind the lines of the American frontier. Colonel Andrew Williamson attacked from South Carolina, and smaller

militia forces from Georgia and Virginia attacked their borders as well. Rutherford's forces alone destroyed thirty-six Cherokee

towns on the Little Tennessee, Tuckaseegee, Oconaluftee, and Hiwassee Rivers, killing men, women, children, and livestock,

executing prisoners and the wounded, and burning crops as well as houses. By the end of the war in 1782, some of the Cherokee

towns had been burnt several times over, and women and children were living in the woods, while Cherokee warriors continued

to support the British. A smallpox epidemic further devastated the Cherokees in 1783. Along with other tribes, they finally

made peace.

Exceptions to the peace included the Cherokee leader Dragging Canoe, who continued

to make war against the encroaching settlers until his death. Also during this time, "mountain men" and "Indian fighters,"

including John Sevier, attacked peaceful Cherokee villages. With the "Chickamauga Cherokees," warriors living on Chickamauga

Creek near present-day Chattanooga, Dragging Canoe harassed the backcountry settlers of Tennessee. At times his cousin Nancy

Ward warned white settlers of impending raids. In gratitude, the "Indian fighters" often spared her home and the town at Chota.

But Dragging Canoe and the Chickamauga Cherokees persisted in military efforts to preserve Cherokee land in Tennessee until

1794, shortly after Dragging Canoe's death.

In 1789, George Washington and Secretary of War John Knox created the "Civilization

Policy." This policy was supposed to solve the "Indian problem" by teaching Indians to live like white people; the policy

also suggested that they intermarry with whites until their native identity disappeared completely.

In the fifty years beginning in

1789 and ending in 1839, (when the last groups on the "Trail of Tears" reached Oklahoma), the Cherokees made an incredible

recovery from defeat and devastation. They transformed themselves into a "civilized tribe" with written language (Sequoyah and the Cherokee Alphabet), schools, churches, farms, commercial enterprises, a written constitution, representative government, and bilingual

newspaper. Centered in what is now northwest Georgia, this remarkable transformation has been called the "Cherokee

Renaissance" by historians.

Changes did not proceed smoothly or in equal measure in different parts of

the Cherokee nation. Factions within the Cherokee nation disagreed about what their relationship should be to white culture

and to the newly formed United States. During this period the Cherokees moved from a decentralized government with towns led

by peace chiefs and war chiefs to a national council with a written constitution. Their struggle to balance autonomous units

with a central government was not unlike that of the new United States. The long legal process of delineating the powers of

states and the powers of the federal government directly affected the Cherokees, and they were active participants in it.

During this period, 1789-1839, Cherokee women began growing cotton and flax,

and they became expert spinners and weavers. Their demand for looms, cards, and spinning wheels outpaced the supplies of the

Indian agents. And no wonder: native women had been weaving baskets, mats, sandals, fishing nets, sashes, and clothing for

thousands of years. At issue for the federal government was whether Cherokee men would become farmers rather than hunters

and warriors. The United States wanted the extensive hunting grounds of all the tribes for white settlement—with a phase

of land speculation where tribal lands taken in treaty by the federal government would then be sold at a profit by the federal

government, the states, and land speculators. The United States also wanted to neutralize warriors by placing them on individual

farmsteads rather than in communal towns, and by making them farmers. While some Cherokee men began farming, most turned to

ranging cattle and hogs in the woods, driving them to market, and they continued to hunt and fish.

The U.S. government, to promote "civilization," partially funded missionaries

to the Cherokees. The Cherokees wanted their children to learn to read and write English. Missionaries offered these skills

along with education in religion, farming, and domestic arts. The Moravians came in 1799, and James Vann allowed them to build

Springplace Mission on his property, near present-day Chatsworth, Georgia. Presbyterian missionaries opened a school in 1804.

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent Congregationalist ministers in 1816, who founded the Brainerd

Mission, whose cemetery still stands in downtown Chattanooga. The Baptists founded their first mission in 1819, for the Valley

Towns, near present-day Murphy, North Carolina, on the Hiwassee River. The Methodists began sending circuit riders in 1824.

During the 1820s, Cherokee men started to become preachers as well, particularly in the Valley Towns. Acceptance of Christianity

did not proceed smoothly. In 1811, Cherokee visionaries received messages that led to a revival of the old traditional religion

for several years. From 1824 to 1827, White Path led a religious and political rebellion calling for a return to traditional

ways, and laid down this cause only when it became apparent that the Cherokee nation needed to be unified in order to deal

with the crisis of removal. (See Indian Removal and Trail of Tears.)

Cherokee government was also changing. Cherokees had been learning to get

along with foreign governments since the early eighteenth century, mainly by assuming a facade of centralized authority, with

"chiefs" and even "emperors." In reality, however, the Cherokee national government was made up of the headmen and elders

of towns. When they met, their town had already reached consensus on an issue, and they brought that decision to the national

council. Consensus and harmony were valued in national government as well as in daily life. From the late 1700s until 1817,

the Cherokee national council included influential men representing all the Cherokee towns as well as young leaders of warriors.

Any Cherokee could attend the meeting and speak.

Gradually this tribal council took on responsibilities formerly carried out

by clans or within villages. In 1808 at Broomestown, it established a light horse police force to cut down on horse stealing

and to enforce inheritance laws (particularly for property passing from men to their children.) In 1810 it canceled all outstanding

blood debts between clans. In 1817 it adopted a constitution creating an Executive Committee and a National Council. Articles

in 1825 delineated property rights, giving Cherokee landholders the right to sell their land to anyone except a non-Cherokee.

By 1828, the council adopted the Cherokee Constitution with three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial.

Perhaps the most remarkable accomplishment of the Cherokee Renaissance was

the creation of a written language by a man who was himself illiterate. George Gist, known as Sequoyah, was born in the Overhill

Towns, and was inspired to create a written form for the Cherokee language. He finally succeeded with a syllabary, which has

a written symbol for each of the eighty-five syllables used to make up the Cherokee language. With the help of his daughter

Ayoka, he demonstrated his system to the Cherokee council in 1821. Within months, a majority of the Cherokee nation became

literate. They wrote letters to each other, began keeping records in this language, and quickly developed a printing press

and bilingual newspaper. The Cherokee Phoenix (literally, "It has risen again") began publication in 1828 and continued until

the state of Georgia stopped it in 1834 because of its anti-removal sentiments.

| Eastern Band of Cherokee to Cherokee Nation |

|

| Eastern Band of Cherokee Indian History |

In spite of the dramatic changes made by Cherokees during this period,

becoming "civilized" by any standard, the Cherokee nation was removed to Indian Territory during the period 1838-1839, leaving only a small group on a remnant of

their once-huge territory. Beginning with Thomas Jefferson's Georgia Compact

of 1802, the government had urged removal of all Indians from the Southeast. The Louisiana Purchase provided a place to send them, the War of 1812 removed the British

as a threat, and by 1817 the federal government was insisting the Cherokees move to Arkansas. A small group, "The Old

Settlers," did so.

A clause in the treaties of 1817 and 1819 allowed Cherokee families to move

off of tribal lands, claim 640 acres each, and apply for citizenship. Many families did this in Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia,

and North Carolina, often remaining on their own farms or town sites in the ceded area. In the following years, only North

Carolina courts upheld Cherokee claims to these lands.

Cherokee removal became inevitable when

gold was discovered in Georgia in 1828 and Andrew Jackson was elected president of the United States in 1829. Georgia rapidly passed

repressive laws, forbidding Cherokees to testify in court and distributing Cherokee

lands to whites in a land lottery. Jackson campaigned for removal, and in 1830 Congress passed the controversial Indian Removal Act by a slim margin.

The Cherokees resisted removal with every possible political and personal

means: editorials, letters, petitions, personal appeals, public speaking tours, and delegations to Washington. In response

to Georgia's legislation, the Cherokee nation pursued the case all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1832 the Supreme Court

ruled that the Cherokee Nation constituted a sovereign nation within the state of Georgia, subject only to federal law; this

decision continues to be the basis for tribal sovereignty for all Native Americans. When John Marshall handed down this decision,

Andrew Jackson is reputed to have said, "He has made his decision, now let him enforce it." Georgia's depredations continued.

In December of 1835, a small group

of Cherokee leaders, unauthorized by the Cherokee nation, signed the Treaty of New Echota at Elias Boudinot's house in their newly built capital named for the old

town of Echota. This "Treaty Party" consisted of Major Ridge, John Ridge, Elias Boudinot, and twenty-four other signers.

Despite immediate protests from the Cherokee National Council, the U.S. Congress ratified this treaty in May of 1836 and gave

the Cherokees two years to remove to Oklahoma.

John Ross, principal chief of the Cherokees, began efforts to halt removal. He collected sixteen thousand signatures of

Cherokee people on a petition against removal—virtually the entire nation—and

took it to Washington, D.C. At home he counseled his people to continue with their daily lives, and to continue to plant and

harvest, giving no indication that they accepted the Treaty of New Echota (Chief John Ross Protests the 1835 Treaty of New Echota). Junaluska, who had saved Andrew Jackson's life at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend,

traveled to Washington to plead the Cherokee's cause, but Jackson would not see him.

Cherokee people recorded sentiments such as the following in many letters,

speeches, and essays during this time. "We the great mass of the people think only of the love we have to our land. For we

do love the land where we were brought up. We will never let our hold to this land go. To let it go will be like throwing

away our mother that gave us birth." Thus wrote Aitooweyeh and Knock Down to John Ross, principal chief.

The government had been preparing for removal by conducting a census of Cherokee

households, estimates of their value, and geographical surveys, particularly in western North Carolina—the area considered

most likely to provide resistance, as well as the most difficult terrain in which to conduct a military action. Soldiers began

constructing garrisons throughout the Cherokee Nation.

In spite of frantic last-minute efforts in Washington, D.C., Cherokee removal

began on May 24, 1838, as specified by the ratified, through fraudulent, treaty. John Ross had sent messages to every village,

counseling people not to resist. He invoked both the Great Spirit and the Old Testament, saying "the desert shall rejoice

and bloom as a rose." (He later surrounded his home in Indian Territory with rosebushes.)

Federal soldiers and state militia rounded up Cherokee people in Georgia,

Tennessee, Alabama, and North Carolina, taking them to thirty-one "forts" throughout

this area (General Winfield Scott and the "Ultimatum" and Gen. Scott's Cherokee Removal Orders). Often looters accompanied the soldiers. From these forts and stockades,

they were taken to eleven internment camps. Neither stockades nor internment camps had facilities for sanitation, cooking,

or sleeping.

These primitive conditions, the abuses of local militia and soldiers,

and tragic results for the first contingents who took the water routes led John Ross to appeal to President Martin Van Buren

to allow him to oversee the rest of the removal, and this appeal was granted. In all,

sixteen detachments of Cherokees left the East, traveling by land and by water through the summer and winter of 1838-39 (Trail of Tears: Mapped Routes). Scholars now estimate that in the removal, in the stockades, on the

trail, and in the first year in Oklahoma, four to eight thousand Cherokees died—one quarter to one-half the population.

John Ross's wife Quatie died after giving her blanket to a sick, crying child, who survived.

One group of Cherokees remained in North Carolina, the Oconaluftee Citizen

Indians. Sixty families, led by Yonaguska, Long Blanket, and Wilnota, had claimed land in their own names under the Treaties

of 1817 and 1819 (Cherokee Treaty of 1817 and Cherokee Treaty of 1819.). Yonaguska had had a vision in 1820 calling for the Cherokees to give up alcohol and stay in their homeland, saying that

they could only be happy in the country where the Creator had placed them. His people followed this revitalizing vision, and

by 1836 were able to successfully appeal to the North Carolina legislature to be allowed to remain

on their lands, mostly near the Oconaluftee River. Petitions signed by local white men attesting to

their sobriety and industriousness aided their case, as did the advocacy of Yonaguska's adopted white son, William Holland Thomas, a trader and lawyer (and future North Carolina Senator).

During removal, three to four hundred Cherokees hid in the wooded mountains

of western North Carolina, particularly on the rugged slopes of the Nantahalas and the Deep Creek watershed below Clingman's

Dome (Kuwahi). Most Cherokees had been arrested in June and moved to Tennessee in July,

and they had heeded Ross's counsel of nonresistance. In November of 1838, however, when only a few federal troops remained

in the mountains hunting fugitives, Tsali (a.k.a. Charlie) and his family killed two soldiers who were

attempting to bring them in.

Tsali and his family lived in a small hollow along the Nantahala River, near

Wesser, North Carolina. The 1835 census lists six household members, all full bloods: three males over eighteen and three

females over sixteen years of age. They owned two cabins, two hothouses (the asi), and one corncrib on thirteen acres of improved

land that included thirty-six peach trees and twelve apple trees. All this was valued at $169. Tsali's neighbors were his

son Lowin, with similar holdings, and Oochella (Euchella), who had once been a leader in the Cowee village where he and Tsali

had lived before that land was taken in the Treaty of 1819.

Tsali and his wife, along with his sons and their wives and children, were

fugitives from May to November of 1838, along with hundreds of others hiding in the rugged Nantahala area, and to the northeast

on the lower slopes of Kuwahi. Soldiers who found them and brought them in say the attack was unprovoked, but Cherokee oral

histories say that the soldiers offended the women and that a baby was killed accidentally. In any case, once soldiers were

killed, the federal government would not rest until retribution was exacted. Troops under Colonel William S. Foster combed

the mountains in cold rainy weather for weeks with no success. William Holland Thomas, the Oconaluftee Citizen Indians, and

a group under Euchella's leadership then began to aid in the search. They found Tsali. Cherokee legend says that he agreed

to come in and be executed so that the other Cherokees would be allowed to stay in the mountains.

After Tsali's execution near Big Bear's farm, the Army gave up its search

for Cherokees in the mountains. Euchella's band, who had been in hiding, were allowed to stay by proclamation of the U.S.

Army, supported by a deposition of local white men. Whether the Army forced Euchella and Yonaguska's people to help bring

in Tsali is not clear, but they certainly would not have been allowed to stay in North Carolina if they had aided Tsali. The

Oconaluftee Citizen Indians under Yonaguska's leadership were allowed to continue living on their private lands along the

Oconaluftee and the Tuckaseegee. Some other Cherokees living on their own deeded land also were able to stay. Those hiding

in the mountains came out. Some Cherokees escaped from the Trail of Tears, or like Junaluska, walked from

Indian Territory back to the mountains of western North Carolina. These people, about one thousand in all, became the ancestors

of today's Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Among them, some still trace their ancestry back to Tsali, Euchella,

Junaluska, and Yonaguska, and the stories of that time are told as though they happened yesterday.

The federal government continued to encourage the Cherokees in western

North Carolina to remove to Oklahoma, but they refused to do so. Aided by William Holland Thomas, Yonaguska's adopted son

and the tribe's acting chief, they managed to stay on their lands. They continued to hunt, fish, and farm in order to survive.

They hired themselves out as laborers on farms owned by whites, and worked as road builders

in the mountains. Some had special skills, such as the blacksmith Saloti (Squirrel) who invented a rifle mechanism that was patented. They gave

their earnings to Will Thomas to buy and hold land in his name until their legal status could be established. (Other

white men also assisted the Cherokees: Albert Siler in Macon County for the Sand Town Cherokees, and Gideon Morris and John

Welch in Cherokee County and Graham County.) Their knowledge of medicinal plants was valued by surrounding communities. Cherokee

women made and traded baskets. They lived in the townships organized by Will Thomas after removal. These townships corresponded

to their representation on the tribal council: Yellow Hill, Birdtown, Painttown, Wolfetown, and Big Cove. Snowbird and Tomotla,

in Graham and Cherokee Counties, also were represented on the council. In every town and community, the gadugi, or work group,

carried on the cultural values of the tribe by helping those in need, a tradition that continues today.

The federal government recognized the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

in 1868, along with other tribes with whom they had made treaties. The Eastern Band then held a general council at Cheoah

in Graham County to adopt a tribal government under a constitution and elected Flying Squirrel (Sawnook, or Sawanugi) as their

first principal chief in 1870. Cherokee ownership of tribal lands as well as individual parcels became legally established.

The Cherokees paid property taxes to the state of North Carolina, and under the laws

of post-Civil War reconstruction, were allowed to vote. Chief Nimrod Jarrett Smith applied for legal status for the tribe as a corporation in North

Carolina, which was granted in 1889.

Shortly before that, in 1887, James Mooney, a young Irish ethnologist, began

work in Cherokee on behalf of the Bureau of American Ethnology. He learned the Cherokee language and collected stories, oral

histories, and medicine formulas by talking with Swimmer, Will West Long, Ayasta, Suyeta, John Ax, and William Holland Thomas.

Mooney's monumental Myths of the Cherokee and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokee remain the classic works on the Eastern Band.

Mooney found that the Cherokee shamans used hundreds of medicinal prayer formulas as well as more than seven hundred plants,

although he believed that these traditional practices were declining.

The turn of the twentieth century found about fifteen hundred Cherokees living

on their individual lands and on tribal land in Swain, Jackson, Graham, Macon, and Cherokee Counties. Their legal status continued

to be debated. In 1895 a federal court ruling on a tribal timber sale found that the Cherokees were wards of the federal government.

Democrats, the majority party in North Carolina, took advantage of this ruling to deny voting rights to the Cherokees, many

of whom had voted Republican in the presidential election of 1884, when the vice-presidential candidate was believed to have

Native American blood. Local registrars did not allow Cherokees to vote in the elections of 1900. Cherokees continued to try

to register and to vote, however. Returning veterans from World War I marched on the Swain County Courthouse but were turned

away, as were Cherokee women who tried to register after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. Cherokees did not

regain the right to vote in local, state, and federal elections until 1946, when veterans returned from World War II and demanded

that right.

During the early part of the century, logging and farming provided income

and subsistence, but the tribe also turned to tourism as a source of income. The first Cherokee Indian Fall Fair, in 1914,

was subsidized by the tribal council specifically to encourage tourism. The opening of the Great Smoky Mountains National

Park in 1934, adjacent to the Qualla Boundary, although controversial within the tribal government, was finally welcomed as a way to attract visitors, who brought a new

source of income. Tourism, however, proved to be a double-edged sword. Although sales of baskets and beadwork encouraged the

continuation and development of those traditions, Cherokees found that they also had to change some traditions to meet the

expectations of their market. Influenced by the Wild West shows of the 1890s, by the stereotypes of patent medicine shows

of the early 1900s, and by movies and finally television, visitors wanted to see natives in Plains Indian costume. Visitors

also preferred shiny black Catawba pottery rather than the ancient stamped pottery of the Cherokees, whose potters have only

recently revived their own distinctive style. These market-driven changes in tradition coexist with the older traditions today.

After World War II, the Cherokees formed three organizations that gave them

a voice in preserving, presenting, and marketing their own culture. The Museum of the Cherokee Indian began with the collections

of Samuel Beck in a log cabin in 1948 and grew into a new building in 1976 and a completely new, high-tech exhibit in 1998.

Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual, a Cherokee crafts cooperative, set standards for quality and authenticity in crafts traditions,

and it provided a year-round market for its members' work. Today it has more than three hundred members. The Cherokee Historical

Association, in partnership with businessmen from surrounding counties, built the Mountainside Theater and created the outdoor

drama Unto These Hills and the Oconaluftee Indian Village and Living History Museum. Millions of visitors have attended the

drama, which tells the story of the Cherokees and the Trail of Tears. The Oconaluftee Indian Village, which re-creates a Cherokee

village ca. 1750, has provided work for crafts demonstrators and informal apprenticeships for youth for more than fifty years.

The twentieth century also brought boarding schools operated by the federal

government, which tried to eradicate Cherokee language and culture by separating children from their families and by using

corporal punishment for speaking the language. Operated from 1892 to 1948, the boarding school in Cherokee educated several

generations of Cherokee children, many of whom never taught the language to their children, so that their children would not

be punished as they were. Cherokee children were also sent away to boarding schools at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and Chilocco,

Oklahoma, to the Hampton Institute in Virginia, and to the Haskell Institute in Kansas. Although the Cherokee boarding school

closed in 1948, the Bureau of Indian Affairs operated schools for the Cherokee until 1990. At that time, the Eastern Band

took charge of the operation and funding of their own schools, instituting courses in Cherokee culture and language in an

ongoing attempt to save the Cherokee language from extinction.

Citizenship, tribal membership, and property ownership of the eastern

Cherokees were influenced by events of the 1920s and 1930s. In 1924, a census of tribal members created the Baker Roll,

which is the standard for membership in the Eastern Band today. (Eastern Band Tribal Membership Requirements.) All land owned by the tribe and by individual members (as

defined by this roll) was placed in trust with the federal government in preparation for allotment, and at this time the federal

government declared all Native Americans citizens. The state government of North Carolina maintained that these citizenship

rights would be valid only when tribal lands were allotted. Allotment never took place, however, leaving the lands in trust

to the federal government and Eastern Band citizenship in limbo. Finally, in 1930 the U.S. Congress passed legislation specifically

giving full rights of citizenship to Cherokee Indians residing in North Carolina. Having individual and tribal lands legally

held in trust enabled the Eastern Band to hold on to their lands, because they could not be sold to outsiders. Today, only

tribal members can buy land from other tribal members or from the tribal land holdings. Although this has maintained the Cherokee

lands, it has also slowed development, because banks are reluctant to loan money for home construction, and businesses are

reluctant to build on leased land.

In the 1950s and 1960s the tribe began efforts to improve living conditions

on the Qualla Boundary. Many tribal members lived in poverty, at standards well below those of surrounding counties. In 1952

a sales tax began financing the Cherokee Tribal Community Services Program, which supports a tribal police department, a fire

department, and the Water and Sewer Enterprise. In 1962 the Qualla Housing Authority began offering low cost loans for house

construction. Other tribal enterprises included the Cherokee Boys Club and trout farming and trout fishing on the boundary

waters. "The Cherokees" factory manufactured moccasins and souvenirs.

In 1984, the Eastern Cherokees and the Cherokee Nation formally met for the

first time since removal. The "eternal flame" was brought back to North Carolina and burns at the entrance to the Mountainside

Theater. Traditions of ceremonial dance have been revived through the efforts of Walker Calhoun, nephew of Will West Long.

Cherokee people are struggling to recover their language, and to preserve their traditions in a cultural renaissance that

began in the late twentieth century.

In 1988 the Indian Gaming Act allowed federally recognized tribes to offer

games of chance on tribal lands, subject to approval by state compacts. Beginning with bingo, the tribe has expanded gaming

facilities to include a casino, which opened in 1997. Because of the casino and resulting new businesses on the boundary (such

as banks, restaurants, hotels, and a grocery store,) full-time jobs with benefits are now available to most tribal members.

Because of income to the tribe from gaming, college education is now possible for any tribal members who are interested. A

kidney dialysis center has been built to serve the nearly one-third of the Eastern Band members who have diabetes. Because

of new jobs as well as per capita payments from gaming proceeds, the standard of living for the Eastern Band now approaches

that of people in surrounding counties.

| Cherokee Indian Culture, Customs, and Heritage |

|

| Cherokee Indian Map |

From the time of removal to the present day, the Eastern Band of Cherokee

Indians has struggled to remain together as a people on their land. A nation within the larger nation of the United States,

they have sustained their own government while dealing with state and federal governments. Located in the remote and rugged

mountains of western North Carolina, they have survived economically through logging, farming, tourism, and now gaming. Their

spoken and written language—once considered evidence of the highest degree of civilization—was forbidden by schools

for a hundred years. Yet the language survives, not only among elders, but among schoolchildren as well. Originally hunters,

farmers, medicine people, artists, map makers, and musicians, the Cherokee people now also work as lawyers, doctors, social

workers, teachers, opera singers, computer technicians, accountants, and in all occupations—many of them on the Qualla

Boundary or nearby. While participating in the global culture of the twenty-first century, many people still practice ancient

ceremonies, weave baskets, and deliberately keep alive the old traditions. Casino profits are establishing a foundation to

develop guidelines for planning and controlling growth while preserving traditional culture and the environment.

Throughout many centuries, then, the Cherokees have balanced old and new,

adapting to change while preserving the essence of what makes them Cherokee: respect for each other and for the earth; caring

for the elders and for youth; treating each day as a gift; preserving harmony through humor and through prayers; speaking

the language, singing the songs, dancing to honor the Creator.

And in 1997 the Eastern Band bought back more than three hundred acres of

land, the Kituhwa village site, home of the first Cherokee village, the town that defined them as a people, Ani-Kituhwa-gi.

(Right) Present-day map of the Qualla Boundary, aka Eastern Band of Cherokee Nation. Courtesy Cherokee, NC

Chamber of Commerce.

Marie Junaluska said, "I think we need to preserve Kituhwa because it was

the mother town. We're searching to find a way to preserve it without digging it up. To me that's a very sacred place. It's

a very peaceful place. If you ever go there, you can feel the peace. The spirit that was there a long time ago is still there.

"There was also a mound there at Kituhwa that you can still see a little bit

of today. And we're in the process of building it back up. Every year the children go there and take a small portion of dirt

and place it on the mound."

Balancing old and new, the Cherokees have come full circle—back to their

origins. Join them on the Cherokee Heritage Trails.

Source: Cherokee Heritage Trails Guidebook, by Barbara R. Duncan

and Brett Riggs.

Recommended Reading: Cherokee

Heritage Trails Guidebook, Barbara R. Duncan and Brett Riggs, The University of North Carolina Press (April

14, 2003) (432 pages). Description:

Celebrating the rich heritage of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, this guide introduces readers to important

sites throughout the Cherokee homeland in western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee, and north Georgia. The book presents

Cherokee stories, folk arts, and historical information as well as visiting information for Cherokee historic sites.

Related Reading:

Recommended Reading: Cherokee History, 1830 Indian Removal Act, 1835 Treaty

of New Echota, 1838 Trail of Tears, and Cherokee Culture and Customs.

Facts and Sources For: Cherokee History, Cherokee Indian Nation Photos, Photographs, Pictures,

Timeline, Summary, Facts, Cherokee Indian Nation Membership Qualifications Information, Government, Culture, Customs, History

|