|

Cherokee War Rituals, Culture,

Festivals, Government, and Beliefs

"Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and assistance in researching your genealogy and heritage."

| Cherokee Reservation Map |

|

| Eastern Cherokee Indian Nation, aka Qualla Boundary, aka Eastern Cherokee Indian Reservation |

The towns of

the Cherokee were usually located near the mouth of small creeks where clear water could be obtained.

Cherokee Indian Rituals

The towns were protected

from enemies by stockade like structures. The towns lay on one side of the river. The stockades were built of posts spaced

about six or eight inches apart with the spaces filled in with saplings and cane. This kind of stockade represents the type

used after the Indians obtained guns from the white man, which made it necessary to place the posts as close as possible to

ward off bullets.

Council houses were always

built on a level place near a stream so the people could take their ceremonial cold plunges during or after ceremonies. The

council house would hold about 500 people and was the most important building in the town. Ordinary persons and women could

not attend the council, but each clan was represented at the council. The Seven Clans of the Cherokee were:

1. aniwadi (Paint Clan)

2. anigategewi (Raccoon

or Blind Savannah, Shawnee

or Wild Potato Clan)

3. ani-sahoni (Blue, Panther

or Wild Cat Clan)

4. ani-gilohi (Long Hair

or hair hanging down, or Wind Clan)

5. anitsiskwa (Bird Clan)

6. aniwahiya (Wolf Clan)

7. ani-awi (Deer Clan).

Cherokees in ancient times

wore feathers of different colors to indicate their clan membership.

Governmental Organization

There was a separation of

power and duties within the government of the Cherokees into two groups--a civil or peace organization and a military or war

organization. Probably the main reason for this separation between the military and civil organization was the fact that while

engaging in war, the warriors became unclean through killing the enemy or even touching a dead body. Whereas the civil organization

being also the religious organization of the communities felt it was necessary for such officials to be kept free from such

uncleanliness. Hence, the separation of duties was essential.

The head chief or principal

chief of the nation was not only the head of the civil government, but also the head of the religion, so he was not only a

chief priest. The chief and his right hand man, the chief speaker, and six counselors formed the main government. Other important

members of the head chief's entourage were his fanner, messenger, speaker, chief priest, and chief for sacrifice. All of these

people lived near the council house and were designated to care for the building as well as the furnishings and ceremonial

regalia that were kept in the building.

The officials of the military

government were the chief warrior and his three main officers and seven counselors. Another important official of the military

government was the War Woman or Beloved Woman. This was a title given to an aged and an honorable woman who may have been

the widow of a former principal chief, since at his death his wife usually officiated until his successor was chosen or it

may have been the eldest distinguished woman of each clan. The War Woman decided whether or not a captive taken in war would

be killed or adopted into the tribe. She also had a vote in deciding whether or not the nation would go to war. She played

a part in the most solemn ceremonies of the Cherokees in ancient times.

Under the old Cherokee code

only two crimes were punishable by death. One was to marry within the clan and the other was to kill a person. Those found

guilty of either of these charges were usually executed in one of the following ways: The sentenced person was sent to war

and pushed out in front so that he would be killed in the ensuing battle; or they might be stoned or killed by some weapon

by members of their own band; or at another time they were taken to the top of a high cliff, and having their elbows tied

behind them and their feet drawn up and tied under them in a sort of kneeling position, they were thrown over the cliff and

slashed to pieces on the rocks below.

| Cherokee Indian Membership and Genealogy |

|

| Cherokee Genealogy Research and Cherokee Indian Membership |

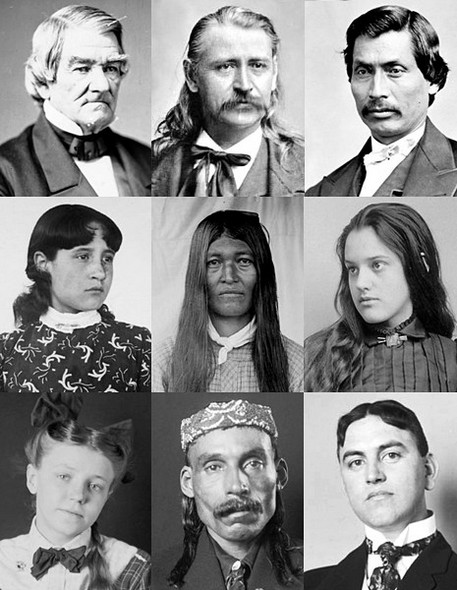

(Right) Cherokee Indians. From

Top, Left to Right: John Ross; Colonel Elias Cornelius Boudinot; Samuel Smith; Lilly Smith; Walini; Marcia Pascal; Lillian

Gross; William Penn Adair; Thomas M. Cook.

The six main festivals held

by the Chief each year were the first New Moon of spring, the New Green Corn Festival, the Green Corn Festival, the first

appearance of the October New Moon (Nuwtiegwa), establishment of friendship and brotherhood and "Bouncing Bush" Festival.

Messengers were sent through the nation to notify the people of the Festivals. Although there was some variation in the number

of days of a Festival, they were always completed within seven days.

At most festivals a sacrifice

of meat was made, the people took ceremonial baths in the water by plunging under seven times. Religious dances were held

most of the night, special wood was gathered for the kindling of special fires, and tobacco was used in a special ceremony.

These festivals were held as a Thanksgiving to God for the fruits of the earth. Prayers were said that God might bless the

corn and meat during the year and make the people healthful. The preliminary Green Corn Feast was held in August and the main

Corn Feast was held in the middle or latter part of September, when the corn was ripe.

The Nuwatiegwa was held

at the time of the first appearance of the October New Moon, when the leaves began to turn yellow and fall. It was held in

honor of the Great New Moon. The Indians believed the earth was created at that season, and their year began at that time.

It was believed that at

this festival each person might look into a crystal to see if he would live through the next year. If they could see themselves

erect as they looked into the stone, it was believed they would live, but if they appeared to be lying down, they would die

before the first spring moon. Those who were to die fasted all day and then had the priest consult the crystal again. If on

the second trial he appeared standing erect, he was ordered to the river and bathed several times and he would be safe.

Today’s Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians are direct descendants of the Cherokee Indians who avoided

the Indian Removal Act and the Trail of Tears.

Beliefs of the Cherokees

The Cherokees had a belief

that there were certain beings that came down from on high and formed the world, the moon and the stars. It was believed that

the world was created at the time of the new moon of autumn, when the fruits of the earth were ripe. The sun seems to have

been the principal object of worship to which they prayed to bring abundant crops, to prevent sickness and so forth. The moon

was also considered to be important in religion and at every New Moon Festival special honor was paid to the moon. Fire was

supposed to have been appointed by the sun and the moon to take care of mankind. It was considered as being intermediate to

the sun and the smoke is symbolized as the messenger of the fire that would make known the petitions of the people to the

sun. The Cherokees believed the morning star was once a wicked priest who killed people by witchcraft. When the Indians planned

to kill him, he took all his shining crystals and flew away to the sky where he appeared as the morning star ever after.

The Cherokees believed that

those who had been good went to a place where it was always light and pleasant and those who had been bad would go to a place

where they would be tortured. It was also believed that a soul lingered about a place where a body had died for as long as

a period of time as the body had lived there and then went back to the place where the person had previously lived for a similar

period of time and so on to each place, staying there as long as the body had stayed. When this regression process was completed

at the person's birth place the soul took its final leave to meet its eternal fate. It was believed there were seven heavens,

with the Supreme Being residing in the first heaven.

Priests and others who had

special religious offices were designated in infancy or childhood, and set apart for that purpose. It appears that some families

had a hereditary right or claim to certain religious offices. The hereditary right or claim was probably inherited through

the mother's family and passed from a man to his sister's name if there were no other women (daughters) to the family.

The Ritual of War

When the chief war officers

became too old to serve the warriors, they nominated someone from among their own war council to replace them. This nomination

was sent to the great chief of the nation, and if he and his counselors approved of the nominee, the candidate was consecrated.

This was done usually at the feast of the Green Corn in August. However, if there was danger threatening the nation, it was

done within twenty days of the time he was nominated. The old war chief selected four distinguished officers to escort the

candidate to the council house. One of the officers walked in front of him carrying a handful of red paint, one walked at

his left with an eagle feather and the other two walked behind him in silent meditation. A special war dress was made for

him of deerskin which was dyed a deep red color. Everything from his leather shirt to his belt, leggings, garter and moccasins

was a deep red color. In the new war chief's acceptance speech, he said he would not stain his hands with the blood of infants,

women, or old men or anyone that for some reason or another is unable to defend himself.

When war was threatened,

the warriors met at the national headquarters where they came under the command of the chief for warfare. During an emergency

such as a threat of war, the red flag of war was raised. The flag was a long pole painted red which had red painted deerskin

fastened to the top. During a war it was carried by a special flag warrior and was set up at the war party campsites where

they met together after a battle. During these encampments they sang the song and then had the war dance.

In the war dance every warrior

carried his main weapon. The dance itself was lead by the right hand man of the war chief. There was no singing involved but

merely the war hoop and the sound of the drum. The warriors went around the circle each one with his left hand pointing to

the center of the circle where the fire and the war flag were located. It is thought this was a kind of dedication by the

individual warriors to do their best in the upcoming battle. The war dance was known as a "te yo hi." The drum used in the

war dance was a pottery jar that had the top covered with raccoon skin with small bells fastened around the rim.

In marching to war, the

first company of warriors was led by the chief warrior. Then came the second company, headed by this right hand man, and then

the third company headed by his speaker, and the fourth company headed by another officer. The last persons in a war party

were the war priest, who was called the fire carrier, his assistant and two of the medicine men.

On the march, there were

four spies or scouts who played an important part in the operation (during the Civil War, they were referred to as "pickets").

Their duties were similar to the enfilade movement of the modern warfare in that they were responsible for protecting the

main force from ambush from the front, the rear and both flanks. The raven spy had a raven skin tied around his neck and scouted

in front; another who had a piece of wolf skin tied around his neck on the right hand side; one with an owl skin scouted on

the left; and one with a fox skin scouted to the rear. The course was marked by the raven spy who went ahead, breaking bushes

and leaving other signs to guide the march.

The battles themselves were

usually brutal hand to hand combat operations carried on in very close quarters. The Cherokees lacked the long range weaponry

that is commonly associated with the Indian wars and the winning of the West simply because that type of weaponry had not

yet been developed.

Following the battle and

upon the war party's return home, the spoils of war were given to the warrior's wife or nearest woman relative. The warriors

who had killed someone or had touched a dead body were considered unclean for a period of four days afterwards. To purify

themselves, it was necessary to bathe themselves and drink only a particular potion. They bathed seven times every night and

every morning. During this time the victory (scalp) dance was danced every night. Sometimes other dances were also performed,

but the warriors were not allowed to dance at all with the women. All the men did not go on the war parties. Someone was needed

to protect the towns. Particularly any warrior who was worried about his wife, family, or property was told to stay at home.

The weapons and equipment

which were used for war were: shields, battleaxes, slings, war clubs, knives, breastplates, spears, helmets, bows and arrows.

(See: Cherokee Indians: Weapons and Warfare.)

The Cherokees in More Recent

Times

The tribe adopted a constitution

and organized a modern government in 1827. About that same time the Georgia legislature passed an act annexing all Cherokee

lands in Georgia and white settlers descended upon the Indian lands of Georgia.

The lands were surveyed into lots, land lots of 160 acres and gold lots of 40 acres each were given to citizens of Georgia

at a public lottery. The Cherokees were not considered citizens of Georgia

thus they were not granted any land allotments for their own lands.

A delegation headed by Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation John Ross was elected and authorized by the National Council of Cherokees to go to Washington

in 1835 to make a plea for federal protection of their land. Immediate results were not forthcoming but at least important

officials in government were made aware of the Cherokee situation. Still, later the Rev. John Schemerhorn induced some Cherokees

to sign the Treaty releasing their lands. However, the Principal Chiefs were all absent and the legality of this Treaty is

questionable. Regardless, the westward immigration began in 1837 with the first group of 466 Cherokees leaving for Oklahoma.

Eventually, 17,000 Cherokees will have traveled on the "Trail of Tears" (enforcement of the Indian Removal Act and Treaty of New Echota in 1835), some old people and children in wagons, but most of the people on foot. One company of aged and sick were sent by water.

Two thousand remained behind.

The land route from Hiwassee

Agency in Charleston, Tennessee, went down the Hiwassee

River to the mouth and then crossed the Tennessee

by ferry and took an old trail south of Pikeville, through McMinnville to Nashville, Tennessee.

After crossing the Cumberland River, it went by way of Hopkinsville,

Kentucky across the State of Kentucky to

Galconda ferry on the Ohio River. The route led across southern Illinois

and crossed the Mississippi to Cape Girardeau,

Missouri, and then onto Indian Territory. Most of the Cherokees

settled in the northeast corner of Oklahoma. Four thousand died either in detention

camps on the journey or afterwards in Indian territory due to exposure on the journey.

In 1865 the State of North

Carolina assured the permanent residence of the Cherokees. In 1868, a general council of the Eastern

Cherokees was held to form a Tribal Government. Nimrod Jarrett Smith was the clerk of the Council. On December 1, 1870, the new government

was inaugurated. The Council members represented Birdtown, Painttown, Wolftown, Yellow Hill, Big Cove and Snowbird. There

are twelve council members. A chief's term is four years.

The economy of the Reservation

is largely dependent upon the tourist industry. A great many tourist attractions are in the immediate vicinity for vacationers

and visitors to see and enjoy.

The Reservation receives the services

of other governmental agencies both local and federal, and steps are taken toward the solution of various problems that are

common to this area.

Source: The Great Smoky Mountains National Park Service Library

Recommended Reading: James Mooney's History, Myths, and Sacred Formulas of the Cherokees (768 pages).

Description: This incredible volume collects the works of the early anthropologist

James Mooney who did extensive studies of the Eastern Cherokee Nation (those who remained in Appalachia) at the turn of the

century. The introduction is by Mooney's biographer and gives a nice overview of both Mooney and the Cherokee Nation,

as well as notes on Mooney's sources. It then goes straight into the first book "Myths of the Cherokee", which starts with

a history of the Cherokee Nation. Continued below...

It progresses from the earliest days, through de Soto, the Indian wars,

Tecumseh, the Trail of Tears, the Civil War and ultimately to 1900. Continuing, it explores Cherokee mythology and storytellers.

This book is truly monumental in its scope and covers origin myths, animal stories, Kanati and Selu, the Nunnehi and Yunwi'Tsundi

(little people), Tlanuwa (thunderbirds), Uktena (horned water snake), interactions with other Nations and numerous other myths,

as well as local legends from various parts of the Southeast (North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, etc). There is also a section

of herbal lore. Mooney closes with a glossary of Cherokee terms (in the Latin alphabet rather than the Sequoya Syllabary)

and abundant notes. We advance to the next book, Sacred Formulaes of the Cherokee, which covers a number of magical texts

amongst the Cherokee Nation. This book does a wonderful job talking about such manuals, mentioning how they were obtained,

going into depth about the Cherokee worldview and beliefs on magic, concepts of disease, healing ceremonies, practices such

as bleeding, rubbing and bathing, Shamanism, the use of wording, explanations of the formulae and so forth. It then gives

an amazingly varied collection of Cherokee formulae, first in the original Cherokee (again, in the Latin alphabet) and then

translated into English. Everything from healing to killing witches, to medicine for stick ball games, war and warfare. Both

books include numerous photographs and illustrations of famous historical figures, Cherokee manuscripts and petroglyphs and

a map of Cherokee lands. Again, this is a truly massive book and even today is considered one of the essential writings of

Cherokee religion. Anyone with an interest in the subject, whether anthropologist, descendant of the Cherokee or just a curious

person interested in Native culture, should definitely give this book a read. I highly recommend it.

Related Reading:

Recommended Reading, try: Cherokee Indians, Eastern Band of Cherokee History,

1830 Indian Removal Act, 1835 Treaty of New Echota, 1838 Trail of Tears, and Cherokee Culture and Customs.

Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Nation,

Tribal, Tribe Membership Enrollment Requirements, Blood, Qualla Boundary, Cherokees, North Carolina Indians, Treaty of New

Echota, Trail of Tears, Researching Cherokee Indian Family Lineage, Genealogy, Ancestry, History, Heritage, Folklore, Myths,

Culture and Customs, Eastern Band of

Cherokee Indian Nation, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Museum of the Cherokee Indian, Tribal Enrollment Membership, Eastern Band

of Cherokee Indian Nation, Tribal, Tribe Membership Enrollment, Census Data and Genealogy Tools.

|