|

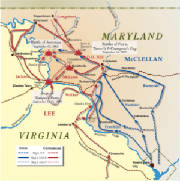

The Maryland Campaign, or the Antietam Campaign (September 4–20,

1862) is widely considered one of the major turning points of the American Civil War. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's first

invasion of the North was repulsed by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan and the Army of the Potomac, who moved to intercept Lee

and his Army of Northern Virginia and eventually attacked it near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The resulting Battle of Antietam was

the bloodiest single-day battle in American history.

The Maryland Campaign, or the Antietam Campaign

Copyright © Civil War Preservation Trust

| Civil War Antietam Campaign Map |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

Several motives led to Lee's decision to launch an invasion. First, he needed

to supply his army and knew the farms of the North had been untouched by war, unlike those in Virginia. Moving the war northward

would relieve pressure on Virginia. Second was the issue of Northern morale. Lee knew the Confederacy did not have to win

the war by defeating the North militarily; it merely needed to make the Northern populace and government unwilling to continue

the fight. With the Congressional elections of 1862 approaching in November, Lee believed that an invading army playing havoc

inside the North could tip the balance of Congress to the Democratic Party, which might force Abraham Lincoln to negotiate

an end to the war. He told Confederate President Jefferson Davis in a letter of September 3 that the enemy was "much weakened

and demoralized."

| Siege of Harpers Ferry Map |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

There were secondary reasons as well. The Confederate invasion might be

able to incite an uprising in Maryland, especially given that it was a slave-holding state and many of its citizens held a

sympathetic stance toward the South. Some Confederate politicians, including Jefferson Davis, believed the prospect of foreign

recognition for the Confederacy would be made stronger by a military victory on Northern soil, but there is no evidence that

Lee thought the South should base its military plans on this possibility. Nevertheless, the news of the victory at Second

Bull Run and the start of Lee's invasion caused considerable diplomatic activity between the Confederate States and France

and England.

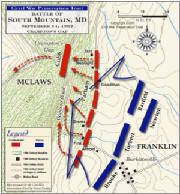

| Crampton's Gap, South Mountain |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

Following his victory in the Northern Virginia Campaign, Lee moved north with

55,000 men through the Shenandoah Valley starting on September 4, 1862. His objective was to resupply his army outside of

the war-torn Virginia theater and to damage Northern morale in anticipation of the November elections. He undertook the risky

maneuver of splitting his army so that he could continue north into Maryland while simultaneously capturing the Federal garrison

and arsenal at Harpers Ferry. McClellan accidentally found a copy of Lee's orders to his subordinate commanders and planned

to isolate and defeat the separated portions of Lee's army.

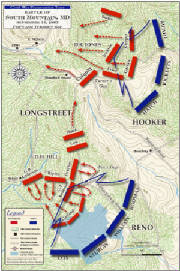

| Fox's & Turner's Gap, South Mountain |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

While Stonewall Jackson surrounded, bombarded, and captured Harpers Ferry

(September 12–15), McClellan's army of 84,000 men attempted to move quickly through the South Mountain passes that separated

him from Lee. The Battle of South Mountain on September 14 delayed McClellan's advance and allowed Lee sufficient time to

concentrate most of his army at Sharpsburg, Maryland. The Battle of Antietam (or Sharpsburg) on September 17 was the bloodiest

day in American military history with over 22,000 casualties. While Lee, outnumbered two to one, moved his defensive forces

to parry each offensive blow, McClellan never deployed all of the reserves of his army to capitalize on localized successes

and destroy the Confederates. On September 18, Lee ordered a withdrawal across the Potomac and on September 19 and September

20, fights with Lee's rear guard at Shepherdstown ended the campaign.

Although Antietam was a tactical draw, Lee's Maryland Campaign failed to achieve

its objectives. President Abraham Lincoln used this Union victory as the justification for announcing his Emancipation Proclamation,

which effectively ended any threat of European support for the Confederacy.

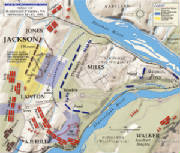

Siege of Harpers Ferry: September

12-15, 1862

| Battle of Antietam - 6:45 a.m. to 7:30 a.m. |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

Learning that the garrison at Harpers Ferry had not retreated after his

incursion into Maryland, Lee decided to surround the force and capture it. He divided his army into four columns, three of

which converged upon and invested Harpers Ferry. On September 15, after Confederate artillery was placed on the heights overlooking

the town, Union commander Col. Miles surrendered the garrison of more than 12,000. Miles was mortally wounded by a last salvo

fired from a battery on Loudoun Heights. Jackson took possession of Harpers Ferry, then led most of his soldiers to

join with Lee at Sharpsburg. After paroling the prisoners at Harpers Ferry, A.P. Hill’s division arrived in time to

save Lee’s army from near-defeat at Sharpsburg.

Battle of South Mountain; Crampton’s, Turner’s, and Fox’s Gaps; September 14,

1862

| Battle of Antietam - 9:15 a.m. |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

After invading Maryland in September 1862, Gen. Robert E. Lee divided his

army to march on and invest Harpers Ferry. The Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan pursued the Confederates

to Frederick, Maryland, then advanced on South Mountain. On September 14, pitched battles were fought for possession of the

South Mountain passes: Crampton’s, Turner’s, and Fox’s Gaps. By dusk the Confederate defenders were driven

back, suffering severe casualties, and McClellan was in position to destroy Lee’s army before it could reconcentrate.

McClellan’s limited activity on September 15 after his victory at South Mountain, however, condemned the garrison at

Harpers Ferry to capture and gave Lee time to unite his scattered divisions at Sharpsburg. Union general Jesse Reno and Confederate

general Samuel Garland, Jr., were killed at South Mountain.

Battle of Antietam, or Battle of Sharpsburg, September 16-18, 1862

| Battle of Antietam - 10:00 a.m to 12:30 p.m. |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

On September 16, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan confronted Lee’s Army

of Northern Virginia at Sharpsburg, Maryland. At dawn September 17, Hooker’s corps mounted a powerful assault on Lee’s

left flank that began the single bloodiest day in American military history. Attacks and counterattacks swept across Miller’s

cornfield and fighting swirled around the Dunker Church. Union assaults against the Sunken Road eventually pierced the Confederate

center, but the Federal advantage was not followed up. Late in the day, Burnside’s corps finally got into action, crossing

the stone bridge over Antietam Creek and rolling up the Confederate right. At a crucial moment, A.P. Hill’s division

arrived from Harpers Ferry and counterattacked, driving back Burnside and saving the day. Although outnumbered two-to-one,

Lee committed his entire force, while McClellan sent in less than three-quarters of his army, enabling Lee to fight the Federals

to a standstill. During the night, both armies consolidated their lines. In spite of crippling casualties, Lee continued to

skirmish with McClellan throughout the 18th, while removing his wounded south of the river. McClellan did not renew the assaults.

After dark, Lee ordered the battered Army of Northern Virginia to withdraw across the Potomac into the Shenandoah Valley.

Battle of Shepherdstown, Boteler's Ford, September 19-20, 1862

| Battle of Antietam - 1:00 p.m. to 5:30 p.m. |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

On September 19, a detachment of Porter's V Corps pushed across the river

at Boteler's Ford, attacked the Confederate rearguard commanded by Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, and captured four guns.

Early on the 20th, Porter pushed elements of two divisions across the Potomac to establish a bridgehead. Hill's division

counterattacked while many of the Federals were crossing and nearly annihilated the 118th Pennsylvania (the "Corn Exchange"

Regiment), inflicting 269 casualties. This rearguard action discouraged Federal pursuit. On November 7, President

Lincoln relieved McClellan of command because of his failure to follow up Lee's retreating army. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside

rose to command the Union army.

Credit: Copyright © Civil War Preservation Trust (You are encouraged to

support the Civil War Preservation Trust located online civilwar.org)

|