|

Battle of Fort Donelson and Battle of Shiloh

Grant In The West--Fort Donelson and Shiloh

by W. B. Wood and Major J. E. Edmonds

A History Of The

Civil War In The United States, 1861-1865

Published in 1905

New York

The Western theatre of war

The Confederate position

Halleck's

sudden resolve

Advance on Fort Henry

Fall of Fort Henry

Result produced

Johnston's plan of campaign

Advance

on Fort Donelson

Failure of the fleet

The Confederates try to cut their way out

Partial success of the Confederate

attack

Arrival of Grant

Smith's successful attack

The Federals recover the lost ground

Surrender of Fort Donelson

Results

of the surrender

Criticism of Halleck's methods

Reasons for Buell's failure to co-operate

Buell occupies Nashville

Evacuation

of Columbus

The strategical position

Difference between Buell's and Halleck's views

Halleck appointed to the supreme

command in the West

Lincoln's error of judgment

Halleck's plan of campaign

Johnston reorganises the Confederate army

Position

of Grant's army

Johnston's advance

Position of Buell's army

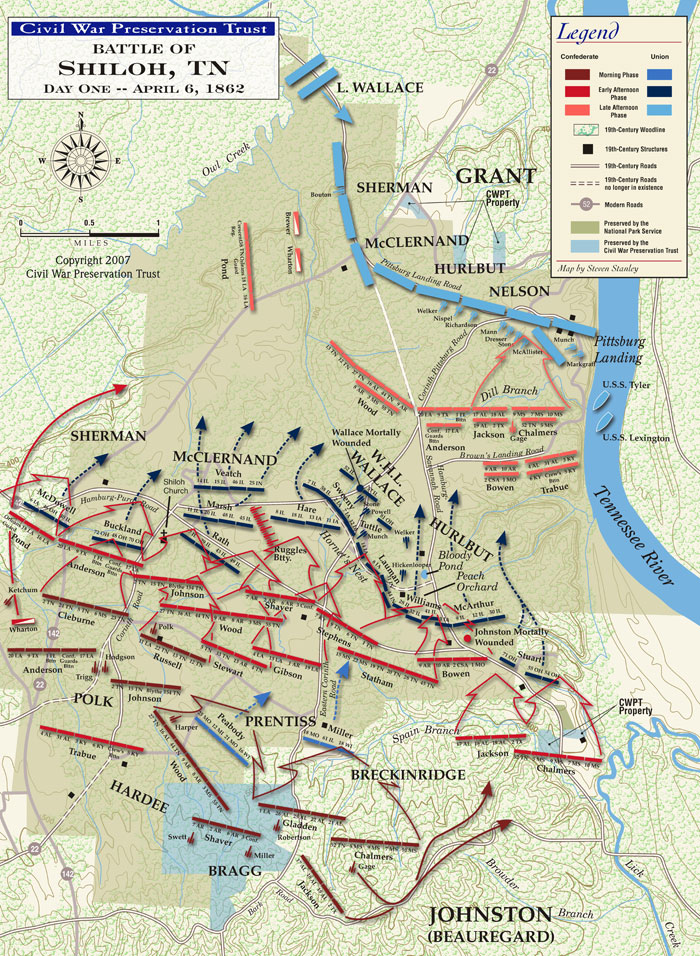

Battle of Shiloh

Federal right driven back

Attack

on Federal centre

Death of Johnston

Federal centre broken

Arrival of Buell

Beauregard calls off his troops

Criticism

of soldiers and generals

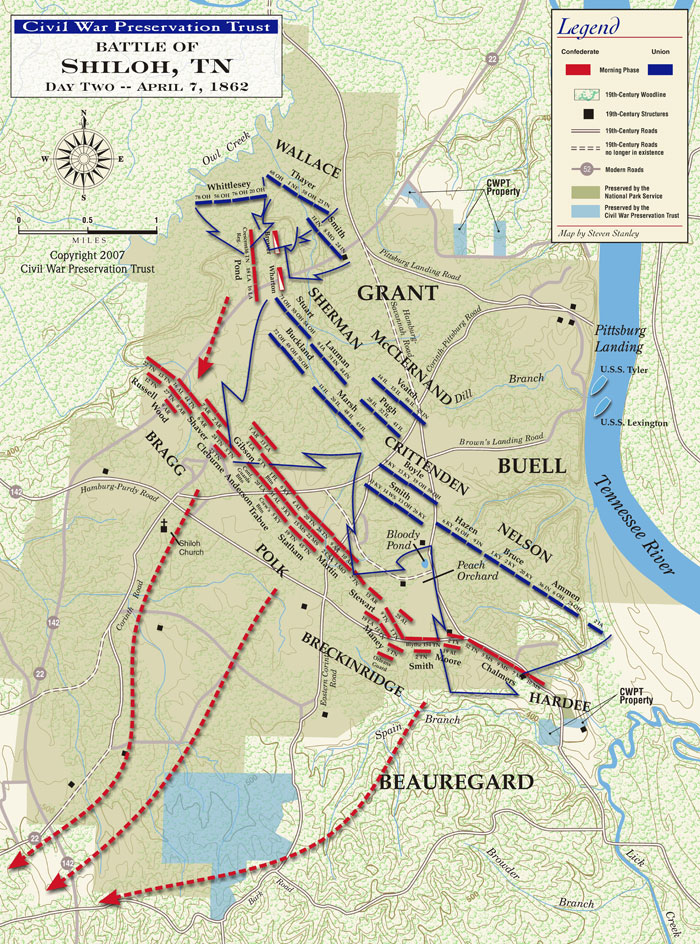

Fighting renewed on the 7th

The Federals recover their lost camps

Pope's success at Island

No. 10

Halleck advances on Corinth

Beauregard evacuates Corinth

Evacuation of Fort Pillow

Naval battle of Memphis

End

of the campaign.

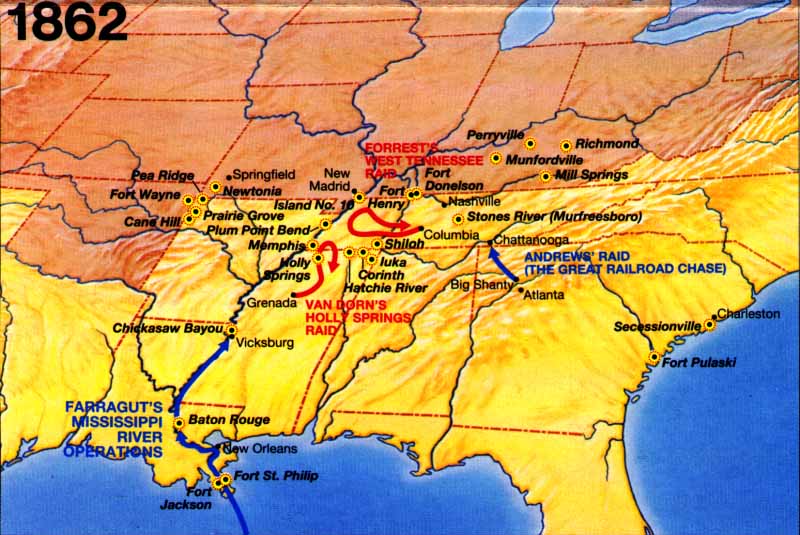

| Shiloh and Donelson Map |

|

| 1862 Battle of Shiloh and Battle of Donelson in Western Theater of the Civil War Map |

WEST

of the Alleghanies the campaign of 1862 opened in the beginning of February. The Confederates under Albert S. Johnston held

a line running from Columbus

on the Mississippi to Bowling Green, and by holding this advanced

position retained possession of a considerable part of Kentucky.

Facing them were General Buell, commanding the Department of the Ohio, who had concentrated

the bulk of his forces at Nolin in order to confront Johnston's main force at Bowling

Green, and General Halleck commanding the Department of the Missouri.

The latter had been too much occupied with restoring order out of the confusion which Frémont had left behind him, to be able

to pay much attention to affairs east of the Mississippi.

But one of his lieutenants, Grant, was in command at Cairo.

It was he who, in September of the preceding year, had forestalled the Confederate general Polk by seizing Paducah, and in

November had moved down the Mississippi with a small force, and fought an indecisive battle with some of Polk's troops at

Belmont opposite Columbus: and he fully appreciated the importance of the issue which was about to be fought out in Kentucky

and Tennessee.

The

Confederate position was one of considerable danger. Although they held the interior lines, and at that time of year the wretched

condition of the roads and the swollen streams presented almost insuperable obstacles to any large force operating by land,

yet the rivers Cumberland and Tennessee afforded an easy advance by water into the very heart of the Confederate power in

the West. The Confederates were painfully aware of their inferiority on water. The superior mechanical skill of the Northerners

gave them an immense advantage in any combat which might be fought out on the Mississippi

and its tributaries. In the West the Confederates had aimed not so much at building gunboats which might resist the advance

of the Federal vessels as at securing strongly fortified positions on the rivers, which would prevent the ships of their foe

from moving up and down at pleasure on their waters. On the Mississippi, above Memphis, they held strong positions at Fort Pillow,

New Madrid and Island No. 10, and Columbus. On the Cumberland and the Tennessee they had constructed Forts Donelson and

Henry to protect the waterway to Nashville and the Memphis

and Charleston Railway.

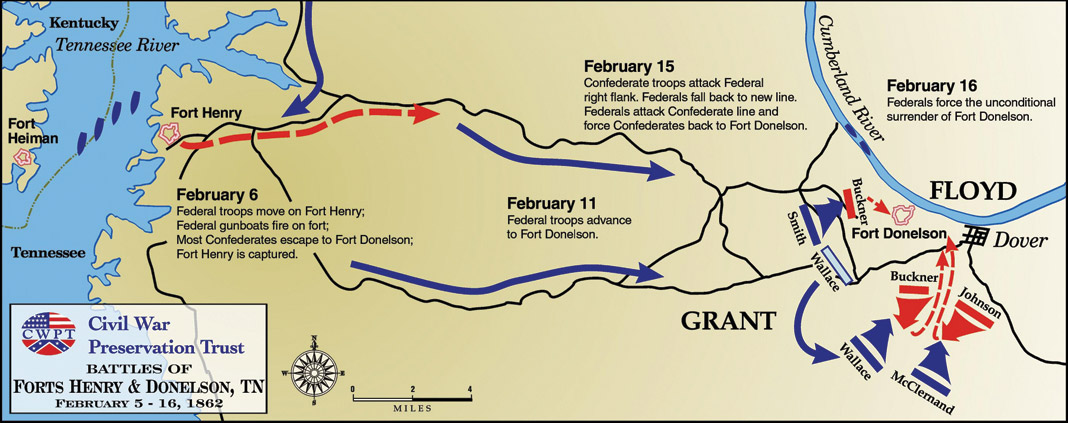

| Civil War Map of Fort Donelson and Fort Henry |

|

| Forts Donelson and Henry |

Buell,

with a full appreciation of the military situation, had been throughout the winter urging upon McClellan the advisability

of a combined movement by land and water upon Nashville. But Halleck had been too much occupied with his

own difficulties in Missouri, and McClellan, partly on political grounds, favoured an advance

into East Tennessee. Suddenly Halleck flung aside his old objections, and on the 30th January

sent word to McClellan that he was ordering Grant to move up the Tennessee and capture Fort Henry. It is

not clear why Halleck so suddenly changed his mind. In all probability he had been convinced by the representations of Grant

and Commodore Foote, who was in command of the naval force, that a movement against Forts Henry and Donelson might lead to

great results. He was a man of considerable ambition and anxious to rival the success of Buell, one of whose lieutenants,

G. H. Thomas, had recently gained a victory at Mill Springs and he hoped by despatching Grant on this expedition to force the hand of the

Government and compel McClellan to abandon his cherished scheme against East Tennessee and give him all the assistance that

he could towards effecting the reduction of the Confederate forts.

These

two fortified posts had been constructed in the summer of 1861 by direction of the authorities of Tennessee. Fort Henry lay on the east bank of the Tennessee,

and twelve miles away was Fort Donelson

on the west bank of the Cumberland. The sites, especially

in the case of Fort Henry,

were not too well chosen, and in both cases the fortifications were too large for defence by a small garrison, and rather

resembled entrenched camps. The two posts, which were under the command of General Tilghman, who had placed

a garrison of 3,000 men in Fort Henry and of 2,000 in Fort Donelson, guarded the bridges, by which the railroad from Bowling

Green to Columbus, connecting the two flanks of the Confederate position, crossed the rivers, and their importance was fully

realised by the Southern commanders.

Grant

received his orders on the 1st February; and on the 3rd the expedition started from Paducah,

forty miles below Fort Henry.

Grant was in command of 15,000 men organised into two divisions under McClernand and C. F. Smith, and was supported by a fleet

of seven gunboats under Foote, of which four were ironclad. By the 5th the whole force had arrived, and Smith's division was landed on the

left bank, where it occupied a high bluff overlooking Fort Henry.

Not

only was the Confederate position commanded from the opposite side of the river, but even on its own bank there were heights,

which once secured by the Federals would have rendered the position of the garrison untenable. Under the circumstances Tilghman decided to send all the infantry to Fort Donelson and

to retain in the fort only a company of artillery. His sole object was to gain time for the rest of the garrison to escape.

On the 6th the fleet advanced to the attack and made short work of the Confederate defences. The fort was built so low that

the guns were close to the level of the water. Various accidents befell some of the guns, and after an hour and a half's bombardment

Tilghman surrendered. The infantry made good their retreat to Fort Donelson.

The

news of the capture of Fort Henry

produced a great effect both in the North and South. It was the first great success won by the Federals, and it had been gained

with startling suddenness. It was hastily assumed, that in its ironclad gunboats the North had an instrument of warfare with

which the Confederate fortified works were powerless to cope. Albert S. Johnston on the following day gave orders for the

abandonment of Bowling Green. He determined with 14,000 men

to fall back to Nashville; at the same time he sent 12,000 men to reinforce the garrison of

Fort Donelson. This latter step was a very strange one. It would probably have been Johnston's wisest course to concentrate as large a force as possible at Fort Donelson and fight Grant before he could

be reinforced. A victory won over Grant would have been the surest means of protecting Nashville.

For if once the Federals got possession of Fort Donelson,

Nashville itself would speedily be at the mercy of their gunboats.

But Johnston, when he sent nearly one half of his army to Fort Donelson, was not contemplating active

operations in the field. He proposed to lock the whole force up within the fortifications, and he relied upon the ability

of his subordinates to extricate their troops, when further resistance seemed useless. It is hardly surprising that General

Floyd, whom he placed in command of the garrison, protested, though vainly, against the whole proceeding.

Grant

had hoped to capture Fort Donelson

on the 8th. But the forecast was too sanguine. The fleet had to descend the Tennessee and

ascend the Cumberland. It had also suffered some injuries

from the guns of Fort Henry

and needed to refit. As the rapid success at Fort Henry

had been gained by the naval force, Grant did not feel himself justified in advancing upon Fort Donelson until it was able to co-operate

in the movement. Not till the 12th did he move his infantry, now reinforced by a third division under General Lewis Wallace.

The same night they arrived before Fort Donelson.

The next day witnessed a good deal of skirmishing and desultory fighting, as the Federals were taking up their positions,

trying to gain some knowledge of the ground and feeling the strength of the enemy.

On

the 14th the fleet attacked, but the result was very different to that anticipated. The batteries, unlike those at Fort Henry, were placed

high above the water and were virtually unassailable. A bend in the river just below the fort enabled all the guns to be brought

to bear upon anything which came within range. After a sharp action, the fleet was forced to retire. Two of the ironclads had

their steering apparatus so damaged that they drifted helplessly out of action, and the other two also received severe injuries.

No impression whatever was made upon the fort. On the 15th Grant left his camp to have a conference with Commodore Foote,

who had been wounded, and it was decided that after the repulse of the gunboats it would be necessary to reduce the fort by

regular siege operations. But on his return to his army Grant found that the situation had entirely altered.

The

Confederate garrison in Fort Donelson

numbered 18,000 men. But its commanders, Floyd, Pillow, and Buckner, overestimated the strength of Grant's force, and believed

that they were largely outnumbered, though they actually at the moment had a slight superiority in numbers over their assailants. Floyd had all along been opposed to an attempt to hold the fort; and he had

special reasons for not wishing to become a prisoner of war, as he was liable to be tried for high treason for his conduct

as Secretary of War in President Buchanan's Administration, and was actually under indictment at Washington for embezzlement of public funds. On the 14th the three generals decided to try and cut their wayout through the

Federal Iines and reach Nashville. The repulse of the fleet

that day failed to give them any increase of confidence.

The

attack was to be made on the morning of the 15th by Pillow's division, which was to break through McClernand's lines on the

Federal right, and open the road to Nashville. Pillow was

to be supported by Buckner, and the latter's division was to form the rearguard and cover the retreat. But no definite arrangements

were made concerning the details of the retreat. It was not even settled whether it was to commence as soon as ever the road

to Nashville should be opened, or whether the movement should

be postponed till the night. No attempt was made to organise a train or provide a supply of food for the army.

The

attack proved successful. McClernand's division was rolled up and thrown back upon the centre, where Wallace's division was

posted, and the road to Nashville stood open. But just at

this point Pillow ordered his victorious troops to return to their own entrenchments. His idea apparently was that when the

road had been opened, the retreat would not take place till after nightfall.

Grant

on his arrival promptly took in the situation. Though his right was beaten, he judged (wrongly, as a matter of fact) that

the enemy must be a good deal demoralised by the fact that they had retired. He immediately ordered Smith, who commanded on the left, to assault the enemy's

lines to "save appearances," and sent an earnest message to Foote, begging that the gunboats would at least make a demonstration

against the fort. Evidently he realised the gravity of the situation, but his admirable composure encouraged his subordinates.

Smith advanced with great gallantry, leading the charge himself. The first line of Confederate entrenchments was carried,

being but feebly defended, as the greater part of Buckner's division had been withdrawn to take part in the attack upon McClernand.

The Federals found that they had gained an elevation which was the key to the whole Confederate position. Buckner returning

with his troops from the scene of the earlier fighting made strenuous efforts to regain this all-important point, but without

success.

At

the same time as Smith advanced to the assault Grant directed McClernand and Wallace to retake the ground which they had lost

in the morning. At nightfall the Confederate position had changed considerably for the worse. The line of their retreat was

again closed to them, and Smith's successful assault had rendered their position in Fort

Donelson untenable. The troops were demoralised and disgusted at having

been recalled after their successful fight; and Grant was receiving reinforments. A Council of War was held that night. Buckner

declared himself unable to hold his position, if the attack were renewed the following morning upon his second line of entrenchments.

The boldest and, under the circumstances, the wisest course would have been to have made during the night all the preparations

possible for a retreat, and in the morning to have made a second attack upon the enemy's right. Though the Federals had reoccupied their old position, yet the troops on the

right were still McClernand's, which had been so severely handled already. It is probable that a considerable part of the

garrison would have succeeded in cutting its way out. But the Confederate Ieaders were in a despairing mood: they had no confidence

in themselves or in their soldiers. Floyd turned over the command to Pillow so as to secure his own escape. Pillow followed

his superior's example.

But

Buckner was of sterner mould, and determined to stand by his troops. Having accepted the command, he at once sent to Grant

to offer to capitulate on conditions. Grant replied with a demand for unconditional surrender. Buckner had no alternative

but to comply, and on the morning of the 16th Fort Donelson surrendered. Floyd and Pillow left by steamer before the capitulation was concluded,

and with them a certain number of infantry escaped also. Forrest, the cavalry commander, with the greater part of his command,

escaped by road. A considerable number of stragglers also got away, but the number of prisoners of war amounted to nearly

12,000. The fall of Fort Donelson

following that of Fort Henry

within ten days filled the South with consternation. The disaster was all the more sudden, because the last news received

had been a despatch announcing a great Confederate victory. A cry went up for vengeance upon the unsucccssful generals, especially

Johnston, the Commander-in-Chief. But President Davis staunchly refused to dismiss a general whom he regarded with justice

as one of the ablest officers in the Confederacy.

The

results of the surrender of Fort Donelson,

both material and moral, were enormous. It secured Kentucky to the Federal cause: it laid

Tennessee open to invasion: it necessitated the evacuation of Nashville

and Columbus. The whole of the first line of Confederate defence

in the West was swept away at a single blow. The South, with its feeble resources, coulld ill afford to lose the services

of the thousands who had become prisoners of war. At the North the victory led to the expectation that the days of the Confederacy

were numbered, and intensified the disappointment which was felt, when these earlier successes were not followed up.

| Tennessee Battle and Battlefield Map |

|

| Tennessee Civil War Map |

The

double success, achieved with a rapidity which was in marked contrast to the methods of other Federal generals, laid the solid

foundation of Grant's military reputation. It gained for him the trust and support of President Lincoln, whicii stood him

in good stead afterward. Yet for the moment it was Halleck, the commander of the Department, who gained the chief credit for

the success won by his lieutenant. It secured him shortly afterwards the supreme command in the West.

But

brilliant as had been the results of the expedition, it was open to severe criticism. When Halleck suddenly made up his mind

to let Grant carry out the scheme, which he persistently advocated, he did not take the trouble to secure either the approval

of McClellan, then Commander-in-Chief of all the Federal forces in the field, or the co-operation of Buell. As he expected,

he forced the hand of the Government. McClellan was obliged to abandon his cherished scheme of an invasion of East Tennessee. But he had

no troops which he could send to Halleck. Buell, who had been led to believe that Halleck would not make any movement up the

Tennessee, had scattered his troops so much that it was no easy task to collect a considerable force, which might be sent

to Grant's aid. Halleck himself imagined that he could spare no troops for the purpose from Missouri. Consequently, after the fall of Fort

Henry, Grant found himself placed, by the ill-judged precipitancy of

his superior officer, in a position of considerable peril. It would have been quite feasible for Johnston to concentrate a superior force against him. Had Beauregard (who had come from the

East to command the troops on the Mississippi under Johnston, with headquarters at Columbus) been commanding the Confederate

forces in the place of Johnston, that would have been the course adopted and a decisive victory would have undone all the

effects of the capture of Fort Henry. Halleck's inconsiderate haste had forced his subordinate to run a great and unnecessary

risk.

Further,

it caused a great deal to be left undone which ought to have been done. Grant had a large enough force under his command at

Fort Donelson to have pushed up the Cumberland in pursuit of Johnston. But

no attempt was made to follow up the Confederate retreat. For ten days after the fall of Fort Donelson Halleck remained without

any plan at all. He had totally failed to grasp the full significance of Grant's success. So far from pressing on into the

heart of Tennessee, and thereby turning the Confederate positions on the Mississippi,

he was afraid that Beauregard would assume the offensive against Cairo, Paducah,

and Fort Henry.

He ordered Grant not to advance, but to send back the gunboats. But Commodore Foote, acting on his own responsibility, pushed

up the river for thirty miles to Clarksville, which he occupied

without resistance, and Grant sent C. F. Smith's division to take possession of that town.

Buell

had taken a long time to make up his mind as to the proper course for him to pursue with reference to Halleck's demands for

help. He was by no means disposed to break up his army and send a considerable part of it to serve under Halleck's command.

A rigid disciplinarian, he had brought the Army of the Ohio

to a high state of efficiency, and was particularly anxious that its esprit de corps, so great an essential in a volunteer

army, should not be impaired by the withdrawal from it of divisions to serve in other armies under other leaders. When he heard that Bowling Green had been evacuated

he determined to send one division by water to Grant, and with the rest of his army to march direct upon Nashville. There can be but little doubt that Buell resented Halleck's action in sending

an expedition against Fort Henry,

and then suddenly calling upon him to send reinforcements to take part in the movement, which Halleck himself had led him

to suppose abandoned. He had a general's natural desire to keep his fine army intact. At the moment of Grant's advance he

was preparing for an advance into East Tennessee, to follow up Thomas' victory at Mill Springs,

and it took him some time to concentrate his troops again for an advance on quite a different line.

On

the 24th February two of his divisions were in possession of Nashville, which Johnston

evacuated after the fall of Fort Donelson.

The conditions of the roads and streams convinced the Federal generals that it was impracticable to follow Johnston, who had

retreated to Murfreesborough, although their united forces would have brought 90,000 men against the Confederate army of less

than 20,000. On the 2nd March Columbus

was evacuated by Beauregard's orders, and almost all the guns and a considerable part of the garrison were removed down the

river to New Madrid and Island No. 10, in order to prevent the further advance of the Federal fleet. General Pope was sent

by Halleck to attack this new position of the Confederates.

| Mississippi Civil War Battle and Battlefield Map |

|

| Mississippi Civil War Map |

As

the pursuit of Johnston had been abandoned it was necessary for the Federal generals to devise some fresh

plan of action. The right strategical course to adopt was to take such a position that Johnston

would be forced either to fight a battle to save his line of communications, or, if he refused to do that, to abandon the

Confederate cause in the West as hopeless. Above all, it was important to prevent Johnston

at Murfreesborough from uniting with Beauregard, who was concentrating a force at Memphis and

Corinth from the garrisons of the abandoned positions on the Mississippi.

The

Memphis and Charleston Railroad offered just such a position

as the Federals required. If Johnston refused to fight for its defence, it would be possible

to sever the West from the East and compel the Confederate forces in the West to fall back upon the Gulf States. At the same time the possession of the railway would enable the Federals to

prevent the junction of Beauregard and Johnston. Both Memphis and the posts on the Mississippi above that city still retained by the Confederates would have to be evacuated when once

Halleck and Buell were firmly established on the line, which connected the Mississippi

with the Eastern States in the Confederacy. The Tennessee

provided the Federals with a safe line of advance against the railroad. A movement up that river would bring them into close

proximity to Corinth, a railway junction of extreme importance.

At that point the Mobile and Ohio Railroad connecting the upper waters of the Mississippi

with the Gulf States intersected the direct line of communication

between East and West. A short distance west of Corinth, a second, the Mississippi Central

Railroad, intersected the Memphis and Charleston

line. The two lines from the south, joining at Jackson, ran

northward through Humboldt and formed the overland line of communication, on which the Confederate forces in Island No. 10

and New Madrid depended for their supplies. At Humboldt a third line came in--the Memphis and Ohio Railway--which was already

broken by the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson. Corinth, Jackson, and Humboldt were three points of strategical importance, but the first was by far

the most important, as its capture would compel the evacuation of the other two positions. To the east of Corinth

a tributary of the Tennessee was crossed by the Memphis and

Charleston line near Eastport, and the destruction of the

railway bridge at that point would seriously embarrass the Confederate movements.

Buell

formed a correct view of the strategical situation. He wished to unite his army and that of Halleck as far up the Tennessee as possible on the east bank, to cross the river and strike

a blow in force at the railroad. Halleck, on the contrary, proposed to send his army up the Tennessee, but to confine its

operations to making raids on the west bank against the Confederate lines of communication, with the exception of one division,

which he intended to send against the railway bridge near Eastport. But the point on which he specially insisted was that

under no circumstances was a general battle to be brought on; to avoid that, the differennt expeditions were, if necessary,

to retreat. He entirely failed to see that the true objective of all his movements ought to have been the Confederate army

in the West, and that its destruction was the one matter of vital importance.

The

consequence of these divided counsels was that after the occupation of Nashville

the Federals made a very poor use of their opportunities. Buell's army remained at Nashville

whilst Halleck made attempts against the Confederate lines of communication, which the condition of the roads and the inclemency

of the weather rendered wholly unsuccessful.

In

the beginning of March, McClellan had been relieved of the command of all the armies of the United

States in the field, in order that he might concentrate his attention upon the Army of the Potomac. On the 11th of the same month President Lincoln yielded to the urgent entreaties of Halleck,

who, ever since the fall of Fort Donelson, had been clamouring for the sole command in the West, and appointed him the commander

of a new Department extending from Knoxville on the east to and beyond the west bank of the Mississippi to be known as the

Department of the Mississippi.

This

appointment placed Buell under Halleck's orders. Lincoln was

unquestionably right to put an end to the system of dual control established by McClellan. A single commander-in-chief in

the West ensured a much-needed unity of movement in the Federal operations. But as certainly Lincoln made a grave mistake in selecting for the command of the new Department Halleck in

place of Buell.

Still,

for the time, Halleck had achieved his object, and was now Commander-in-Chief of the Federal forces in the West. Missouri,

which had absorbed so much of his attention during the earlier stages of the war, had been permanently secured to the Federal

cause by the victory of General Curtis at Pea Ridge over the Confederate general, Van Dorn, on the 7th and 8th March. Curtis followed up his success by marchiiig through Arkansas

without encountering any serious opposition, and came out on the bank of the Mississippi

in the following July. Halleck, in taking over his new command, had nothing to fear on the west side of the Mississippi. As his attempt to destroy the Confederate lines of communication on the west

of the Tennessee had failed, he determined to carry out

the plan of campaign which from the first had been urged upon him by Buell, now his subordinate. He directed the Army of the

Ohio to move to Savannah on the east bank of the Tennessee with a view to uniting with Grant's army, which was concentrating at Pittsburg Landing, nine

miles above Savannah on the opposite bank. The combined armies

were then to move on Corinth, which wasas twenty miles distant

from Pittsburg Landing. The position for the Federal camp had been selected by C. F. Smith, who had been temporarily in command

of the advance up the Tennessee, owing to a misunderstanding

between Halleck and Grant. It was a strong position, as the flanks were protected by the Tennessee

and its tributaries, and could have been rendered impregnable by a single night's work at entrenching. But the use of entrenchments

had not as yet been recognised by either combatant. There was, however, one cardinal defect about the position. It had no

line of retreat. If the Confederates should concentrate a superior force against Grant before he was reinforced by Buell,

the Federal army if beaten in battle would have no alternative except to capitulate.

Johnston

and Beauregard were quick to seize the opportunity. They saw a chance of defeating the largely superior forces at Halleck's

disposal in detail. About the 18th March Johnston reached Corinth

with 20,000 men, having marched from Murfreesborough by way of Decatur. He found there General Bragg, who brought a force of 10,000 men from Pensacola. Beauregard ordered his troops to assemble at the same point.

On the 29th March Johnston formally assumed command of the Army of the Mississippi, as it was now styled, numbering about 40,000 men with 1000 pieces of artillery.

Apparently Johnston had lost confidence in himself

after his repeated failures to check the Federal advance, and urged Beauregard, the victor of Bull Run,

to assume the chief command. But the latter refused to supersede his superior officer. The Confederate army was organised

into three Corps under Polk, Hardee, and Bragg, all West Point graduates and soldiers of decided ability, with a reserve of infantry

under Breckinridge, who had been Vice-President of the United States,

when Buchanan was President.

By

the 1st April Grant had concentrated at and near Pittsburg Landing about 45,000 men. His army was divided into six divisions commanded by W. T. Sherman, Prentiss,

McClernand, Lewis Wallace, Hurlbut, and W. H. L. Wallace--the last named was commanding in place of C. F. Smith, who had injured

his leg so seriously that he was obliged to leave his command, and before the end of April he died of the effects of his accident.

Grant laid himself open to severe criticism by continuing to keep his army at Pittsburg Landing, after the operations against

the enemy's lines of communication had been found to be impracticable. The Landing had been selected as the temporary base

for the operations, but it was the height of imprudence to turn it into a permanent camp within twenty miles of the enemy,

unless it was strongly entrenched. But throughout this part of the campaign Grant displayed a sense of security which was

strangely out of place. His easy successes had made him careless and unduly contemptuous of the enemy. He knew that they were

collecting in force at Corinth. He ought to have realised

that his exposed position gave them an opportunity which such able officers as Johnston and Beauregard were hardly likely

to let slip. Yet he had made up his mind that the Confederates would not venture to assume the offensive. His own headquarters

were at Savannah, nine miles away from his army and on the

opposite bank of the river. No plan of battle had been arranged. The divisional commanders had been allowed to fix their camps,

not with a view to mutual support, but as it suited the convenience of each commander. No systematic cavalry reconnaissances

had been carried out along the roads leading to Corinth. There

was no regular outpost line in front of the camp. Not a single precaution had been taken to guard against a surprise.

It

must be said that Halleck shared to the full the light-heartedness of his lieutenant. He suffered him to remain in his insecure

position: he gave Buell no hint that the safety of Grant's army depended upon the prompt arrival of his forces. He proposed

to come at his leisure to Pittsburg Landing to assume the command of the two armies concentrated there, and then to commence

the advance on Corinth. He gave the Confederate generals no

credit for enterprise or even common sense; he believed them to be committed to a purely defensive policy.

Johnston was anxious to concentrate as large a force as possible against

Grant, in order that he might inflict a crushing blow. Van Dorn, after his defeat at Pea Ridge, had been ordered to bring

to Corinth all the troops that he could raise from Missouri

and Arkansas. Johnston waited

for his arrival as long as he thought safe; but on the night of the 2nd April, hearing that Buell was moving rapidly towards

Savannah, he ordered an advance the following day. It was his intention to fall upon the Federal camp in the early hours of the

5th, but the wretched condition of the roads and the inexperience of officers and men prevented the troops being in position

at the appointed time. Forrest's cavalry had encountered a certain amount of opposition, whilst leading the advance. Beauregard,

when it became clear that the attack must be postponed, was in favour of abandoning the whole enterprise and of returning

to Corinth, believing that the Federals must know of their

advance and were decoying them into a trap. Johnston, however,

resolved to go on. His army had come to fight and not to retreat: another movement to the rear would destroy the confidence

of the soldiers in their general and fatally impair the moral of his army. The attack was fixed for the morning of

the 6th.

Meanwhile

Buell's army of five divisions, numbering about 37,000 men, was drawing near. It had been marching steadily but without undue haste, and had been delayed for

twelve days at Duck River

where a bridge had to be built. How completely Halleck had failed to impress upon Buell the need for promptly joining Grant

is shown by the fact that Buell asked for and actually received permission to take his army not to Savannah,

but to a landing-place opposite Hamburg, a town ten miles

above Pittsburg Landing. It was by a mere accident that the orders to that effect miscarried. About noon of the 5th (Saturday)

the leading division under Nelson reached Savannah. Grant,

however, declined to send it across the river immediately, because he thought there would be be no fighting; some day early

in next week would be time enough.

About

two miles out from Pittsburg Landing, upon the Corinth road stood Shiloh Church. There Sherman had his headquarters, and his division formed the right of the Federal army: in rear

of him McClernand had pitched his camp. The centre of the position was held by Prentiss' division, half a mile from Sherman's

left, across a second road leading to Corinth, and behind it lay Hurlbut's division, whilst more than half a mile beyond Prentiss,

and resting upon the river, was Stuart's brigade, detached from Sherman's division. W. H. L. Wallace's division was still

further to the rear, and Lewis Wallace's was at Crump's Landing, some five miles further down the river. Two gunboats in the

river served to strengthen the left flank.

| Map of Shiloh Battlefield on April 6, 1862 |

|

| Shiloh Battlefield |

About

6 a.m. on the 6th the battle of Shiloh commenced. At 3 a.m. on that Sunday morning Prentiss had sent out a brigade to reconnoitre. This

force suddenly encountered the Confederate advance under Hardee, and was quickly driven in. So swift was the onslaught that

the Federals were quite taken by surprise. The fighting, which lasted throughout the day, was at first a succession of independent

battles waged by the different divisions. The Federal front line, held by Sherman's and Prentiss' divisions, was promptly

driven back upon the divisions in their rear. The ground was thickly wooded, broken by swamps and ravines, and naturally favourable

to the defensive. The Confederates, being raw soldiers and led by inexperienced officers, did not keep their formation very

accurately. A good many seem at once to have left their ranks in order to plunder the captured camps. The Federals consequently

found time to form a second line of defence. But the lack of organisation now made itself felt. Their line was divided into

three distinct sections at some distance from each other, so that the flanks of the respective divisions were open to a turning

movement. On the right Sherman's and McClernand's divisions stubbornly resisted the onslaught of Hardee's and Polk's Corps.

Their right was covered by Owl Creek, but their left flank was completely exposed. As the attacking line extended, the Federals

were forced to fall back from one position to another to escape being driven into the Creek, on which their right rested.

Eventually they took up a position on Snake Creck, into which Owl Creek runs, covering the bridge, by which Lewis Wallace's

division was expected to arrive from Crump's Landing, and this they held to the close of the day's fighting. In McClernand's

report it was stated that this was the eighth position which his troops had occupied since the fighting began.

In

the centre the divisions of Prentiss, Hurlbut, and W. H. L. Wallace held a very strong position known as the "Hornets' Nest."

Up the wooded slope the Confederate right, composed of Bragg's and Breckinridge's commands, was hurled again and again in

unavailing charges. Johnston had left Beauregard in general

charge of the whole field to take under his own personal direction the movements of the right wing. He directed a succession

of frontal attacks against the Hornets' Nest, which was practically impregnable to any but a flank movement. About 2.30 p.m.

he was killed, and Bragg succeeded to the command of the right wing. He initiated a flanking movement, which was rendered

the easier by the withdrawal of Stuart's brigade, forming the left of the Federal line, about 3 p.m. Hurlbut, whose division

formed the left centre, finding himself outflanked, fell back to the Landing. By his withdrawal Prentiss' left flank became

exposed, and that general was forced to change front. He and Wallace, however, continued to hold their position with great

resolution until about 5 p.m. Polk moved his corps over from the left to Bragg's assistance. Wallace himself was killed, but

nearly all his division made good their retreat. The remnant of Prentiss' division, however, was surrounded and forced to

surrender.

But

this obstinate resistance had given time for the sorely needed reinforcements to come up. Nelson's division had been hurried

up from Savannah to a point opposite Pittsburg Landing, and

there was ferried across. By 5:30 p.m. the leading brigade was in position behind a deep ravine covering the Landing. Grant

had got together some twenty guns to hold this last position, and such of his infantry as he had been able to rally. But the

bluff overlooking the river was crowded with an ever-increasing stream of fugitives, whose numbers have been estimated as

high even as15,000.

Against

this last line of the defence Bragg was advancing to complete the defeat of the Federal army. But the sun was already sinking,

and Beauregard, who after Johnston's death had succeeded to

the command, determined to draw his troops off. In his judgment it was too late in the day to hope to gain any further success,

and he wished to give his soldiers a good night's rest in view of the hard fighting which lay before them next day. His orders

reached one of Bragg's divisions in time to prevent its further advance. But the other division, moving before Beauregard's

order arrived, went in to the assault with the utmost gallantry. But it had no supports: the ammunition supply ran short, and all its efforts

were powerless to carry it across the ravine in the face of the heavy artillery fire and Buell's troops, now engaged for the

first time during the day. The gallant but useless struggle was continued until nightfall, when the Confederate division withdrew.

The

battle of Shiloh, like the First Bull Run, is typical of encounters between volunteer armies.

It was the first pitched battle fought on a large scale in the West. On both sides the lack of discipline and the unrestrained

instinct of the individual to think for himself and to take such steps as seem most likely to secure his own safety were to

be seen in the large number of stragglers, and of men who, not from cowardice but simply from lack of military habit, left

their ranks and moved to the rear when the case seemed hopeless. This was especially noticeable in the case of the Federals.

The stream of fugitives increased with each successive movement of tbe sorely pressed divisions to the rear. It has been estimated

that at the close of the day's fighting Grant had not more than 12,000 men under arms (including Lewis Wallace's division

from Crump's Landing, which took no part in the fighting of the 6th).

This

feature was not so noticeable on the actual day of battle in the Confederate ranks, as they were acting on the offensive and

buoyed up by the hope of winning a signal victory. And, indeed, the vigour with which the Confederates attacked at Shiloh

contrasts favourably with the methods of the Federals, when they were the attacking force at Bull Run.

But after the fighting was over and it was recognised that the attempt to annihilate Grant's army, before it could be reinforced,

had failed, there was a steady stream of fugitives anticipating on their own responsibility the order for a general retreat

on Corinth, which reduced Beauregard's force for the next day's fighting to 20,000 men.

Nor

was the conduct of the commanding officers on either side above criticism. Grant exercised but little personal control over

the course of the battle. He showed himself at the different parts of the field, and did his utmost to encourage and rally

his beaten troops. But throughout the day on the Federal side the absence of a single controlling mind was noticeable.

Johnston also failed to display any marked tactical ability in the handling

of his troops. The original plan had been that the Federal left should be turned, and the whole army thus forced away from

the river, on which their hope of reinforcements depended. But Johnston,

by committing himself to a succession of frontal attacks against the almost impregnable position of the Federal centre, abandoned

the original plan, and caused his troops to suffer very heavy loss without obtaining any counterbalancing advantage.

During

the night of the 6th Lewis Wallace's division arrived from Crump's Landing. Its late arrival was due to a misunderstanding. Three divisions of Buell's army were also brought across the river, and by the

morning of the 7th Grant had under his command 25,000 fresh troops, who had not borne the burden and toil of the previous

day's fighting. He ordered an advance against Beauregard's sorely tried troops as soon as it was light, and by 5 a.m. the

battle was renewed. Beauregard on this day displayed tactical ability of a high order. He never allowed his army to become

involved in a pitched battle, and yet whilst steadily falling back lost no opportunity of striking a counterblow at any Federal

force which pressed too closely in pursuit. His retreat never degenerated into a rout.

| Map of Shiloh Battlefield on April 7, 1862 |

|

| Battle of Shiloh |

The

fiercest fighting of the day was on the Corinth road between the Purdy road and Shiloh

Church. For nearly six hours Bragg held his position there with splendid

tenacity, and prevented the Federals from cutting the line of retreat to Corinth.

Between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m. Grant, having regained the positions which his first

line had held at the commencement of the previous day's fighting, desisted from any further attempt to crush the Confederate

army. There was no apparent reason why he should not have pressed the pursuit till nightfall. But of neither of these two

eventful days did Grant rise to the height of the occasion.

The

losses on both sides were very heavy; in killed and wounded they were nearly equal, the Federal loss being slightly over 10,000,

whilst that of the Confederates was a few hundreds short of that number. But the Federal loss in prisoners and missing was

much heavier than that of their opponents. In Prentiss' division alone 2,200 were taken prisoners.

Having

abandoned the pursuit on the afternoon of the 7th, Grant made no attempt to resume it, but waited at Pittsburg Landing for

Halleck's arrival. The Commander-in-Chief joined his armies on the 11th April. He displayed no eagerness to advance, but preferred

to wait until Pope's army should join him. Pope, with 21,000 men, had been sent to operate against the Confederate position

at Island No. 10 and New Madrid, and after some very arduous work, including the cutting of a canal twelve miles long, forced the surrender of 7,000 Confederates on the 8th April. The only position

on the Mississippi still held by the Confederates above Memphis

was Fort Pillow,

eighty miles below New Madrid. Pope had been originally ordered to continue his movement down the river and attack this post.

But before he had actually commenced operations against it he was recalled to join Halleck, which he did on the 21st April. In spite of this reinforcement, which raised his army to 100,000 men, Halleck

allowed another week to pass by before he commenced a very cautious advance on Corinth.

On the 1st May Beauregard was reinforced by 15,000 men brought from the opposite bank of the Mississippi by Van Dorn. The army under his command now numbered over 50,000, but he did

not venture to give battle to a force double his own strength. Halleck's forward movement was a succession of slow approaches.

He carefully entrenched each position, and impressed upon his lieutenants that under no circumstances were they to allow themselves

to be drawn into a pitched battle. For over a month the operations against Corinth

dragged slowly on until, on the 29th May, Beauregard, finding himself in danger of being hemmed in, evacuated the town in

the night. The movement was quite unexpected by Halleck, and Beauregard withdrew the whole of his army in safety to Tupelo, some fifty miles to the south on the Mobile

and Ohio Railroad. There he had the advantage of an excellent water supply and a salubrious climate; and his army, which had

suffered considerably from sickness in its entrenchments at Corinth,

rapidly recovered its health.

The

evacuation of Corinth necessitated the abandonment of Fort

Pillow. The garrison was withdrawn on the 3rd June. The Federal fleet

pushed on to Memphis, where, on the 6th, a Confederate fleet of gunboats and rams was encountered

and destroyed, and the same day Memphis, from which the garrison

had already been withdrawn, was occupied by the Federals.

With

the occupation of Corinth and Memphis,

the spring campaign in the West came to an end. Much had been accomplished. The Federal army was firmly established across

the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. The Mississippi

had been opened to Vicksburg. Kentucky

and West Tennessee were in the hands of the Federals. But there had been also much left undone.

The opportunities for destroying the Confederate army had been signally missed. Before long that army was as strong as ever,

and it was the Confederates who next assumed the offensive in the West.

NOTE

ON SHILOH

A keener controversy has raged

over the battle of Shiloh than perhaps over any other battle of the Civil War. In the Federal

ranks the longstanding jealousy between the Armies of the Tennessee and the Ohio

finds free expression in the divergent accounts of the battle, which come from the partisans of one or other, and there has

been no more damaging criticism of Grant's methods than that penned by Buell, commander of the Army of the Ohio. Similarly on the Confederate side, the admirers of Johnston

and the enemies of Beauregard have sought to saddle the latter with the responsibility of the defeat, and have claimed that

Johnston had won a victory, which Beauregard threw away after

the commanding general's death.

The

first point at issue is the alleged surprise of the Federal army. Though Grant and Sherman have both denied that any surprise

of their troops took place, yet it is impossible to ignore the overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It is probably enough

that Bragg somewhat exaggerated, when he spoke (Johnson and Buel (editors): Battles & Leaders of the Civil War:

p. 558) of many of the enemy being surprised and captured in their tents, but the undeniable fact remains that the Federal

leaders were not expecting an attack, that they had made no preparations for such a contingency, and that the scouting on

the Federal side was so slovenly that a great army was allowed to assemble within two miles of Sherman's headquarters without

its presence as an army being detected. The surprise of the 11th Corps at Chancellorsville was hardly more complete than that

of the Army of the Tennessee at Shiloh, though from a variety

of causes the subsequent course of the fighting on the two fields followed different lines. Halleck, Grant, and Sherman were

all three convinced that the enemy was definitely committed to a defensive policy, and that there would be no serious fighting

until Corinth was reached.

The

initial advantage in the fight lay then with the Confederates, and was retained by them till almost the close of the day.

The absence of the commanding general during the early stages of the, battle, which commenced before 6 a.m., whilst Grant

did not reach Pittsburg Landing till after 8 a.m. at the earliest, combined withi the total lack of preparation for a possible

battle, as is evidenced by the fact that one of Sherman's brigades was encamped on the extreme left two miles from the division

to which it belonged, prevented the Federals from forming an organised line of battle and enabled the attacking force to defeat

their opponents in detail. Grant, indeed, says (Johnson and Buel (editors): Battles & Leaders of the Civil War:

p. 473) that "with the single exception of a few minutes after the capture of Prentiss, a continuous and unbroken line was

maintained all day from Snake Creek or its tributaries on the right to Lick Creek or the Tennessee

on the left above Pittsburg."

The

following brief summary of events, taken from Buell's Shiloh Reviewed (Johnson and Buel (editors): Battles &

Leaders of the Civil War: p. 487-526), presents a different, and, it is believed, a more accurate account of the day's

fighting. Skirmisming began with Prentiss' troops. Prentiss drew up his main line about a quarter of a mile in front of his

camp, and held that position till the enemy passed him on the right to attack Sherman, whose left regiment immediately broke.

Prentiss retired, renewed resistance in his camp, and then fell back in still greater confusion to the line, which Hurlbut

and Wallace were forming half a mile to his rear. McClernand, owing to Sherman's

left wing giving away, was unable to form his Iine until he had fallen back some 300 yards with the loss of six guns. Of Sherman's division Hildebrand's brigade on the left very soon disappeared.

Buckland's brigade of the same division made a stout resistance of about two hours at Oak Creek, but with McDowell's on the

right was ordered back to form a line on the Purdy road 400 yards to the rear in connection with McClernand's right. This

effort was defeated; five guns were lost, and Sherman's division

as all organised body disappeared. McDowell's brigade was the last to go, about 1 p.m. McClernand afraid, as all connection

with the left was gone, of being cut off from the river, retired in the direction of the Landing, and about 3 p.m. took up

a fresh position along the River road north of Hurlbut's original headquarters. In the meantime Stuart's brigade on the extreme

Federal left had fallen back to a position in prolongation of and on the left of Hurlbut's, Wallace's and Prentiss' line in

the Hornets' Nest, but without having any connection with it. The Federal centre held their position in the Hornets' Nest

from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. By 3 p.m. the right wing, consisting of Sherman's and McClernand's divisions and one brigade, sent to

its aid by Hurlbut, had given way, and Stuart's brigade on the left had also fallen back. At 4 p.m. Hurlbut, owing to the

pressure on his left in consequence of Stuart's withdrawal, fell back, and the Confederates, massing on both flanks as well

as in the front of the Hornets' Nest, compelled the surrender of Prentiss and 2,200 men shortly after 5 p.m. When the last

Confederate attack was made by Chalmers' and part of Jackson's

brigades, Hutlbut was in line behind a battery of siege-guns posted half a mile from the river, but there was no organised

resistance for a distance of 500 yards from the Landing. A rifled battery had been placed in position there, but the gunners

were leaving their posts when Ammen's brigade of Buell's army arrived and repulsed the Confederate attack. The rifled battery

could effect nothing against the attacking force, which was sheltered in the ravine, and the fire of the gunboats was equally

harmless.

Grant

(Johnson and Buel (editors): Battles & Leaders of the Civil War: p. 475) states that "before any of Buell's troops

had reached the west bank of the Tennessee firing had almost

entirely ceased; anything like an attempt on the part of the enemy to advance had absolutely ceased." In proof of this view

he cites the fact that Buell's loss on the 6th consisted of two killed and one wouiided, all the casualties being in the same

regiment. Buell's contention, however, is that it was the presence of Ammen's brigade which prevented the final charge made

by the two Confederate brigades from cutting off the Army of the Tennessee

from the Landing.

The

nature of the battlefield, largely covered with wood and intersected by ravines, favoured the defensive and prevented the

Confederates from utilising their cavalry for purposes of pursuit. This circumstance enabled the Federals to hold on till

reinforcements arrived, but those reinforcements came not from Lew Wallace's division at Crump's Landing, but from Buell's

Army of the Ohio.

Grant

also asserts (Johnson and Buel (editors): Battles & Leaders of the Civil War: p. 476) that victory was assured

when Lew Wallace arrived, even if there had been no other support. Apart from the contention that Wallace's division would

have been too late to save Grant's army, had it not been for the intervention of Ammen, the record of the next day's fighting

seems to show, that with only Wallace's division to reinforce his beaten army, Grant would have been hard put to it, even

to hold his ground against Beauregard. On the 7th the fighting on the left was entirely done by the Army of the Ohio, whilst on the right the honours were borne off by McCook's division

of the same army.

In

an elaborate argument Buell maintains that the official map misrepresents the position of Grant's army on the night of the

6th. He says that this map extends Grant's line full half a mile too far to the west, placing Hurlbut's division on the front

actually occupied by McClernand, McClernand's division on and 400 yards beyond Sherman's ground, and Sherman within the Iines

occupied by the enemy. He goes on to say that the revision of the map made nineteen years later by Sherman is still more misleading,

giving Grant a battle front of 2 1/2 miles instead of one mile at the most, not only extending Grant's line too far to the

west but at least half a mile too far to the south. He considers that Sherman's

line was not more than three-quarters of a mile from the river and more than a mile distant from the bridge over Snake Creek,

by which Lew Wallace's division was expected, and which it could in no practical sense be said to cover.

Amidst

such conflicting testimony it seems impossible to arrive at any definite conclusion without avowing oneself a partisan of

one side or the other. Ropes (The Story of the Civil War; A Concise Account of the War in the United States of America Between 1861 and 1865. Vol. II, 79-80) expresses himself

very cautiously to this effect: "that this attack [of the two Confederate brigades], might have succeeded if it had been made

before the troops from Buell's army arrived, is by no means improbable." One may perhaps go so far as to say, that without

Buell's reinforcements Grant would not have won the battle of the 7th, whilst his position on the 6th might have been one

of the gravest peril.

On

the Confederate side the rival claims of Beauregard and Johnston have been urged with a personal animosity happily lacking

in the Federal controversy. Not only facts but also motives are called in question, and no important statement made by the

one side is left uncontradicted by the other. The first point at issue is, to which of the two generals belongs the credit

of conceiving the offensive movement against the Federal army at Pittsburg Landing. Colonel Johnston, A. S. Johnston's son,

who was not himself at Shiloh and in his account of the battle seems to place much reliance upon a monograph furnished him

by General Bragg, written, as, it would seem, with the express purpose of discrediting Beauregard, states that it was his

father who fixed upon Corinth as the point of concentration and determined upon the offensive movement against Grant, whilst

Beauregard, so he asserts, had all along favoured a defensive policy and wished to limit the movement upon Pittsburg Landing

to a reconnaissance in force. On the other hand, Beauregard maintains that from his arrival in the western theatre of war

he advocated an offensive policy, but that Johnston was steadily opposed to it, and that only

with great difficulty did he persuade Johnston to join him at Corinth instead of continuing his intended retreat on Stevenson.

There

is no doubt that the Confederates were a day late in making their attack, and if it had been made on the 5th, as originally

designed, their chances of success would have been greater. For this delay Colonel Johnston holds Beauregard to blame. He

states that the orders for the march issued from Beauregard's headquarters were not the same as those which Johnston had originally approved, and that the change was the cause of the delay. Beauregard

maintains, and his contention is supported by the evidence of two of his staff, General Jordan, Adjutant-General of the army,

and Colonel Chisolm, that the orders issued on the morning of the 3rd were those approved by Johnston on the previous night, and that the delay was due to the misconduct of the Corps

commanders.

Beauregard

claims that as soon as fighting commenced on the 6th Johnston

gave him general control of the field and confined his whole attention to the extreme right. On Beauregard's theory Johnston's death did not cause any appreciable Iull in the combat; perhaps

there was an interval of fifteen minutes whilst Bragg was organising a movement to outflank the Hornets' Nest. Colonel Johnston

holds that his father exercised a general control over the whole field of battle up to his death, and speaks of him as being

on different parts of the field at different times. He considers that Johnston's death caused

a lull of over one hour in the battle, and that after that melancholy event there was no longer any sign to be found in the

Confederate ranks of that unity of purpose and combination of movement which the presence of Johnston on the field had thus far ensured.

After

the capture of Prentiss and his troops Colonel Johnston states that "all the Corps commanders were at the front and in communication:

a line of battle was formed, and all was ready for the last fell swoop." According to Bragg, that final assault was never

made, as Beauregard "at Shiloh, two miles in the rear," sent orders for the withdrawal of

the troops. According to this view it was not Grant's reserve artillery or Ammen's infantry brigade which saved the Federal

army, but Beauregard's fatal order issued under a misconception of the state of affairs at the front.

Beauregard,

however, contends that after Prentiss' surrender "no serious effort was made by the Corps commanders to press the victory.

The troops had got out of the hands either of Corps, divisional, or brigade commanders, and for the most part at the front

were out of ammunition. Before the order (for withdrawal) was received, many of the regiments had been withdrawn out of action,

and really the attack had practically ceased at every point." Colonel Chisolm states that he was on the extreme left with

Hardee till almost dark, up to which time no orders had arrived to cease fighting. There seems, however, some doubt as to

the reason which led Beauregard at 6 p.m. to call off his troops. According to his own account he knew that Buell's advance-guard

had crossed the river, and he therefore withdrew his troops to make preparations for the defensive battle which he knew would

take place next day. But according to General Jordan's version, a telegraphic despatch had been received at the Confederate

headquarters to the effect that Buell was marching towards Decatur,

and Beauregard called off his troops because he felt sure of being able to annihilate Grant next day at his leisure.

Of

these two utterly contradictory versions of the battle of the 6th, the evidence seems on the whole to favour Beauregard's.

The animus in Colonel Johnston's narrative is very marked. General Johnston at the opening of the war was regarded as the

ablest soldier of the South. His failure to hold Kentucky and Tennessee caused dismay and astonishment, and his friends and admirers were anxious to represent

their hero as stricken down in the moment of gaining a victory, which would have retrieved all his previous disasters. For

that purpose it was necessary to cast the blame of throwing away the victory, which was as good as won, upon Beauregard.

Recommended

Reading: Shiloh and the Western Campaign

of 1862. Review: The bloody and decisive two-day

battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862) changed the entire course of the American Civil War. The

stunning Northern victory thrust Union commander Ulysses S. Grant into the national spotlight, claimed the life of Confederate

commander Albert S. Johnston, and forever buried the notion that the Civil War would be a short conflict. The conflagration

at Shiloh had its roots in the strong Union advance during the winter of 1861-1862 that resulted in the capture of Forts Henry

and Donelson in Tennessee. Continued below…

The offensive

collapsed General Albert S. Johnston advanced line in Kentucky and forced him to withdraw all the way to northern Mississippi. Anxious to attack the enemy, Johnston began

concentrating Southern forces at Corinth, a major railroad center just below the Tennessee border. His bold plan called for his Army of the Mississippi to march north and destroy General Grant's Army of the Tennessee

before it could link up with another Union army on the way to join him. On the morning of April 6, Johnston

boasted to his subordinates, "Tonight we will water our horses in the Tennessee!"

They nearly did so. Johnston's sweeping attack hit the unsuspecting Federal camps at Pittsburg

Landing and routed the enemy from position after position as they fell back toward the Tennessee River.

Johnston's sudden death in the Peach Orchard, however, coupled

with stubborn Federal resistance, widespread confusion, and Grant's dogged determination to hold the field, saved the Union

army from destruction. The arrival of General Don C. Buell's reinforcements that night turned the tide of battle. The next

day, Grant seized the initiative and attacked the Confederates, driving them from the field. Shiloh

was one of the bloodiest battles of the entire war, with nearly 24,000 men killed, wounded, and missing. Edward Cunningham,

a young Ph.D. candidate studying under the legendary T. Harry Williams at Louisiana

State University, researched and wrote Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 in 1966. Although it remained unpublished, many Shiloh

experts and park rangers consider it to be the best overall examination of the battle ever written. Indeed, Shiloh

historiography is just now catching up with Cunningham, who was decades ahead of modern scholarship. Western Civil War historians

Gary D. Joiner and Timothy B. Smith have resurrected Cunningham's beautifully written and deeply researched manuscript from

its undeserved obscurity. Fully edited and richly annotated with updated citations and observations, original maps, and a

complete order of battle and table of losses, Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 will

be welcomed by everyone who enjoys battle history at its finest. Edward Cunningham, Ph.D., studied under T. Harry Williams

at Louisiana State

University. He was the author of The Port Hudson Campaign: 1862-1863

(LSU, 1963). Dr. Cunningham died in 1997. Gary D. Joiner, Ph.D. is the author of One Damn Blunder from Beginning to End: The

Red River Campaign of 1864, winner of the 2004 Albert Castel Award and the 2005 A. M. Pate, Jr., Award, and Through the Howling

Wilderness: The 1864 Red River Campaign and Union Failure in the West. He lives in Shreveport,

Louisiana. About the Author: Timothy B. Smith, Ph.D., is author of Champion Hill:

Decisive Battle for Vicksburg (winner of the 2004 Mississippi

Institute of Arts and Letters Non-fiction Award), The Untold Story of Shiloh: The Battle and the Battlefield, and This Great

Battlefield of Shiloh: History, Memory, and the Establishment of a Civil War National Military Park. A former ranger at Shiloh,

Tim teaches history at the University of Tennessee.

Recommended

Reading: The Shiloh

Campaign (Civil War Campaigns in the Heartland)

(Hardcover). Description: Some 100,000 soldiers fought in the April 1862 battle of Shiloh, and nearly 20,000 men were killed

or wounded; more Americans died on that Tennessee

battlefield than had died in all the nation’s previous wars combined. In the first book in his new series, Steven E.

Woodworth has brought together a group of superb historians to reassess this significant battle and provide in-depth analyses

of key aspects of the campaign and its aftermath. The eight talented contributors dissect the campaign’s fundamental

events, many of which have not received adequate attention before now. Continued below…

John R. Lundberg

examines the role of Albert Sidney Johnston, the prized Confederate commander who recovered impressively after a less-than-stellar

performance at forts Henry and Donelson only to die at Shiloh; Alexander Mendoza analyzes the crucial, and perhaps decisive,

struggle to defend the Union’s left; Timothy B. Smith investigates the persistent legend that the Hornet’s Nest

was the spot of the hottest fighting at Shiloh; Steven E. Woodworth follows Lew Wallace’s controversial march to the

battlefield and shows why Ulysses S. Grant never forgave him; Gary D. Joiner provides the deepest analysis available of action

by the Union gunboats; Grady McWhiney describes P. G. T. Beauregard’s decision to stop the first day’s attack

and takes issue with his claim of victory; and Charles D. Grear shows the battle’s impact on Confederate soldiers, many

of whom did not consider the battle a defeat for their side. In the final chapter, Brooks D. Simpson analyzes how command

relationships—specifically the interactions among Grant, Henry Halleck, William T. Sherman, and Abraham Lincoln—affected

the campaign and debunks commonly held beliefs about Grant’s reactions to Shiloh’s aftermath. The Shiloh Campaign

will enhance readers’ understanding of a pivotal battle that helped unlock the western theater to Union conquest. It

is sure to inspire further study of and debate about one of the American Civil War’s momentous campaigns.

Recommended Reading: Shiloh: The Battle

That Changed the Civil War (Simon & Schuster). From Publishers Weekly: The

bloodbath at Shiloh, Tenn.

(April 6-7, 1862), brought an end to any remaining innocence in the Civil War. The combined 23,000 casualties that the two

armies inflicted on each other in two days shocked North and South alike. Ulysses S. Grant kept his head and managed, with

reinforcements, to win a hard-fought victory. Continued below…

Confederate

general Albert Sidney Johnston was wounded and bled to death, leaving P.G.T. Beauregard to disengage and retreat with a dispirited

gray-clad army. Daniel (Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee) has crafted a superbly researched volume that will appeal to

both the beginning Civil War reader as well as those already familiar with the course of fighting in the wooded terrain bordering

the Tennessee River.

His impressive research includes the judicious use of contemporary newspapers and extensive collections of unpublished letters

and diaries. He offers a lengthy discussion of the overall strategic situation that preceded the battle, a survey of the generals

and their armies and, within the notes, sharp analyses of the many controversies that Shiloh

has spawned, including assessments of previous scholarship on the battle. This first new book on Shiloh

in a generation concludes with a cogent chapter on the consequences of those two fatal days of conflict.

Recommended Reading: Shiloh--In Hell before Night. Description: James McDonough has written a good, readable and concise history of a battle that the author

characterizes as one of the most important of the Civil War, and writes an interesting history of this decisive 1862 confrontation

in the West. He blends first person and newspaper accounts to give the book a good balance between the general's view and

the soldier's view of the battle. Continued below…

Particularly enlightening is his description of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston, the commander

who was killed on the first day of the battle. McDonough makes a pretty convincing argument that Johnston

fell far short of the image that many give him in contemporary and historical writings. He is usually portrayed as an experienced

and decisive commander of men. This book shows that Johnston

was a man of modest war and command experience, and that he rose to prominence shortly before the Civil War. His actions (or

inaction) prior to the meeting at Shiloh -- offering to let his subordinate Beauregard take command for example -- reveal

a man who had difficulty managing the responsibility fostered on him by his command. The author does a good job of presenting

several other historical questions and problems like Johnston's

reputation vs. reality that really add a lot of interest to the pages.

Recommended Reading: Seeing

the Elephant: RAW RECRUITS AT THE BATTLE OF SHILOH. Description: One of the bloodiest battles in the Civil War, the

two-day engagement near Shiloh, Tennessee,

in April 1862 left more than 23,000 casualties. Fighting alongside seasoned veterans were more than 160 newly recruited regiments

and other soldiers who had yet to encounter serious action. In the phrase of the time, these men came to Shiloh

to "see the elephant". Continued below…

Drawing on

the letters, diaries, and other reminiscences of these raw recruits on both sides of the conflict, "Seeing the Elephant" gives

a vivid and valuable primary account of the terrible struggle. From the wide range of voices included in this volume emerges

a nuanced picture of the psychology and motivations of the novice soldiers and the ways in which their attitudes toward the

war were affected by their experiences at Shiloh.

|