|

Battle of Aldie

Aldie Civil War History

Battle of Aldie

Other Names: None

Location: Loudoun County, Pennsylvania

Campaign: Gettysburg Campaign (June-July 1863)

Date(s): June 17,

1863

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick [US]; Col.

Thomas Munford [CS]

Forces Engaged: Brigades

Estimated Casualties: 415 total

Result(s): Inconclusive

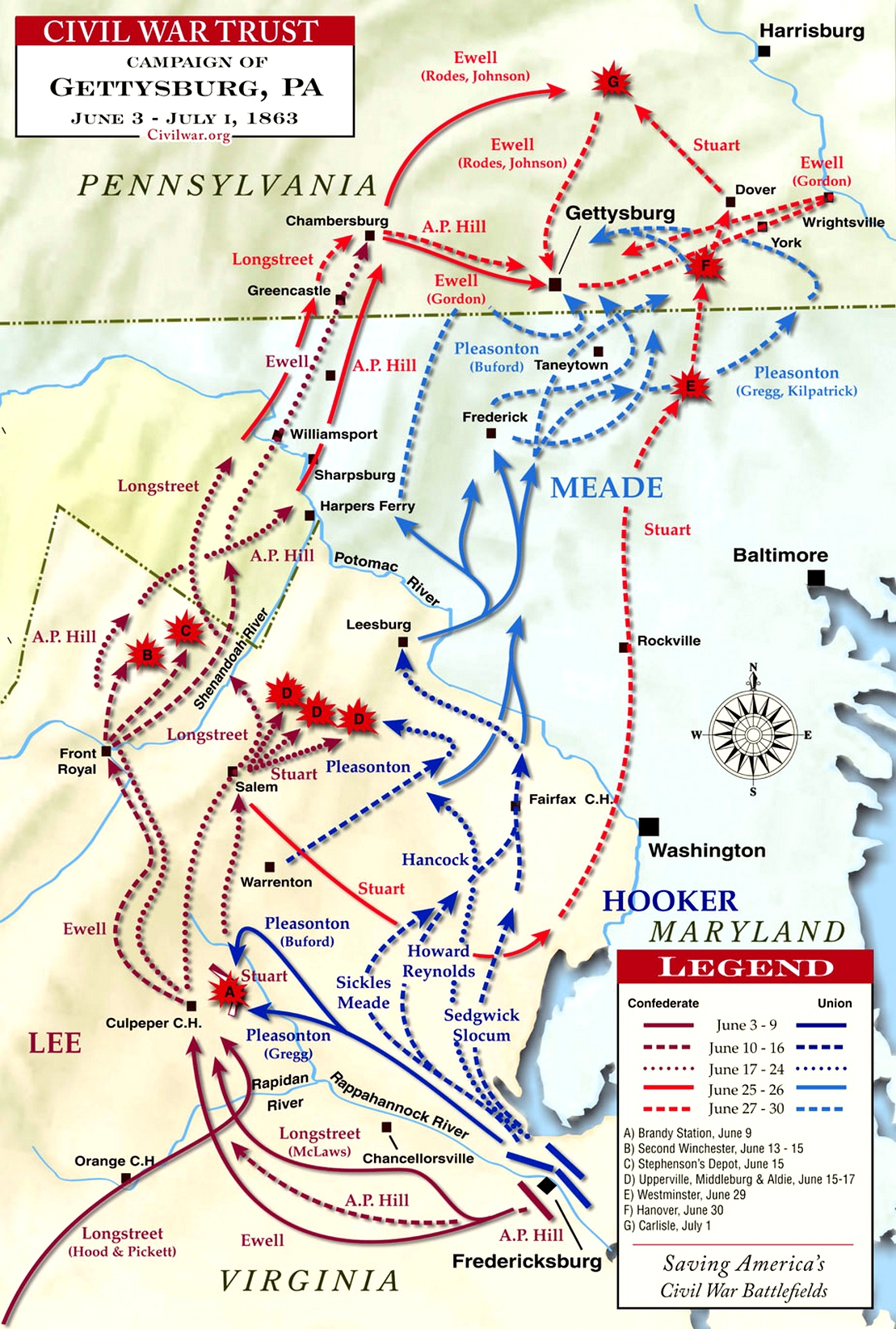

| Battle of Aldie Map |

|

| Civil War Battle of Aldie and Battlefield Map |

Introduction: Stuart’s cavalry screened the Confederate

infantry as it marched north behind the sheltering Blue Ridge. The pursuing Federals of Kilpatrick’s brigade, in the

advance of Gregg’s division, encountered Munford’s troopers near the village of Aldie, resulting in four hours

of stubborn fighting. Both sides made mounted assaults by regiments and squadrons. Kilpatrick was reinforced in the afternoon,

and Munford withdrew toward Middleburg.

Background: Late in the spring of 1863 tensions grew between Union commander Joseph Hooker

and his cavalry commander Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton because of the latter's inability to penetrate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's

cavalry screen and gain access to the Shenandoah Valley to locate the Army of Northern Virginia, which had been on the move

since the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May. On June 17, Pleasonton decided to push through Stuart's screen. To accomplish

his goal he ordered Brig. Gen. David McM. Gregg's division from Manassas Junction westward down the Little River Turnpike

to Aldie. Aldie was tactically important in that near the village the Little River Turnpike intersected both the Ashby's Gap

Turnpike and Snicker's Gap Turnpike, which respectively lead through Ashby's Gap and Snickers Gap of the Blue Ridge Mountain

into the Valley.

Battle: Early that very same morning, Colonel Munford led the 2nd and 3rd Virginia Cavalry

eastward across the Loudoun Valley from Upperville through Middleburg to Aldie on the Bull Run Mountains on a reconnaissance

and forage mission. He established a line of pickets in Aldie to watch for enemy activity and withdrew his two regiments northwest

of town on the Snicker's Gap Turnpike to camp on the farm of Franklin Carter.

About 4 p.m., Gregg's advance column of the 2nd and 4th New York, 6th Ohio, 1st Maine, 1st Rhode Island, and

1st Massachusetts, under the command of Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick arrived in Aldie. Just west of the village the 1st Massachusetts

encountered Munford's pickets and drove them back. Around the same time, the rest of Munford's brigade (the 1st, 4th, and

5th Virginia Cavalry, under the command of Col. Williams Carter Wickham) arrived at Dover Mills, a small hamlet on the Little

River west of Aldie. Wickham ordered Col. Thomas L. Rosser to take the 5th Virginia to locate a campsite closer to Aldie.

As they moved east they ran into the Massachusetts men and easily drove them back through Aldie to the main Union body. After

positioning his sharpshooters (50 men of Company I under Capt. Reuben F. Boston) east of the William Adam farmhouse, Rosser

deployed west along a ridge that covered the two roads leading out of Aldie and awaited the arrival of the Federals, as well

as Munford and Wickham. As Rosser withdrew west, the 1st Massachusetts, with aid from the 4th New York, charged against what

they believed to be a retreat. Rosser's line held and he mounted a countercharge in concert with a sharp volley from the sharpshooters

he had placed on his left and easily drove the Federals back, securing his hold on the Ashby's Gap Turnpike.

Kilpatrick then turned his attention towards the Snicker's Gap Turnpike. An artillery duel ensued and more

cavalry on both sides soon arrived. A furious fight erupted, which at first went in favor of Munford as Federal charges were

met, stopped, and then forced back by the withering volley of sharpshooters entrenched along a stone wall. The 1st Massachusetts

Cavalry was trapped in a blind curve on the Snicker's Gap Turnpike and was destroyed, losing 198 of 294 men in the eight companies

that were engaged. One detachment under Henry Lee Higginson was virtually wiped out in hand-to-hand fighting. The tide finally

turned as Union reinforcements charged into the fray in the fading light and the 6th Ohio overran Boston's detachment on the

Ashby's Gap Turnpike, capturing or killing most of his men. The fighting died down around 8 p.m. as Munford withdrew his command

west towards Middleburg.

| Battle of Aldie |

|

| Battle of Aldie was fought during the Gettysburg Campaign |

Aftermath: Munford did not consider Aldie as a defeat as his withdrawal coincided with an

order from Stuart to retire, as more Federal cavalry had been sighted at Middleburg. Union casualties were 305 dead and wounded,

with the Confederates losing between 110 and 119. Aldie was the first in a series of small battles along the Ashby's Gap Turnpike

in which Stuart's forces successfully delayed Pleasonton's thrust across the Loudoun Valley, depriving him of the opportunity

to locate Lee's army.

Analysis: The opening battle of the Gettysburg campaign, Brandy Station,

and the climactic battle at Gettysburg have eclipsed the intervening cavalry battles of Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville

in the history books. But the fight for Loudoun Valley was significant on a number of levels. Considered individually,

each battle might not rank high in terms of forces engaged and casualties. Considered together, however, it is clear

that the week’s fighting represented a substantial effort on both sides. At various times, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart

committed each of his five brigades, numbering near 9,000 troopers, to the task of defending the Blue Ridge Mountain gaps.

Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton eventually pushed all of his available 8,000 men into the task of penetrating the Confederate

cavalry screen and, in addition, called on infantry support. Altogether some 19,000 soldiers struggled in the valley

from June 17-21.

|

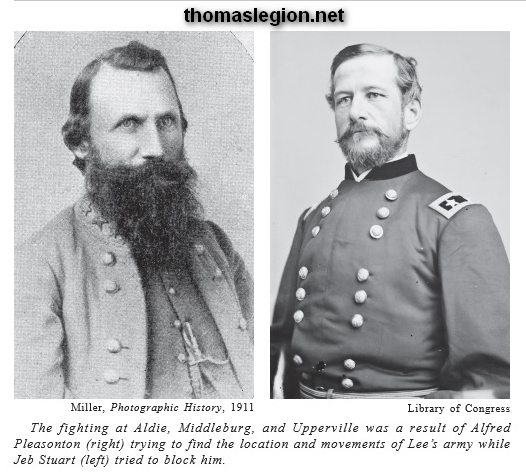

| (L) Stuart; (R) Pleasonton |

The cavalry battle of Brandy Station yielded 1,400 casualties from among 21,000 engaged. Only eight

days later the adversaries met again on very different terrain. The steep-banked streams, ravines, stonewalled fields,

and constricted roads of Loudoun Valley prevented the extensive troop deployments and open maneuvering seen at Brandy.

At Brandy Station combat was concentrated in time and spread out over the open fields. In Loudoun Valley a comparable

intensity of effort was concentrated along fairly restricted corridors of movement and spread out over five days. Although

records are incomplete, historians have estimated combined casualties for Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville as 1,360 (850

Northerners and 510 Southerners) with roughly similar losses among the mounts—an attrition of 8 percent of the forces

engaged. Brandy Station was the largest cavalry battle thus far in the war, but the week’s fighting in Loudoun

Valley drained an equivalent number of men and mounts from the ranks.

Loudoun Valley also witnessed a struggle of wills that permeated future cavalry operations in Virginia.

Stuart’s adjutant Henry B. McClellan wrote, “The battle of Brandy Station made the Federal Cavalry. The

fact is that up to June 9, 1863, the Confederate cavalry did have its own way... and the record of its success becomes almost

monotonous... But after that time we held our ground only by hard fighting.” It is true that the Union troopers

had been remarkably buoyed by their performance at Brandy Station, but in Loudoun Valley they proved to an attentive public,

to themselves, and to their adversary that Brandy had been no fluke. Once derided as hopelessly outclassed by Stuart’s

cavaliers, the Federal horsemen aggressively took “hard fighting” to their enemy with an offensive spirit hitherto

lacking. If Brandy Station marked the coming of age of the Federal cavalrymen as so many have observed, then the battles

for Loudoun Valley proved their newfound confidence. Stuart’s troopers, for their part, had to begrudge the fact

that they now faced a foe that matched them steel for steel.

In mid-June 1863, Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart faced the task of defending the principal gaps in the Blue Ridge—Ashby’s

Gap and Snicker’s Gap—against Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton’s Federal divisions. The two turnpikes

leading across Loudoun Valley to the gaps diverged at Aldie, complicating Stuart’s mission. Pleasonton could concentrate

his full force on either turnpike, while Stuart had to spread out his forces to cover both. The danger for Stuart was

that his brigades could become isolated from one another and defeated one at a time. The general nature of the terrain,

though, favored Stuart’s defense. Federal mobility was fairly closely restricted to the roads by the numerous

streams, stone walls, and fences that crisscrossed the landscape. The stone walls provided Stuart’s dismounted

skirmishers with readymade fortifications. Stuart selected his defensive positions carefully and could afford to give

up ground in a series of delaying actions. Pleasonton, on the other hand, had no choice but to attack each successive

position that he encountered. To accomplish his own mission—to discover the whereabouts of the infantry columns

of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia--Pleasonton had to pierce the Confederate cavalry screen.

Much of the cavalry fighting in Loudoun Valley was dismounted. Troopers fanned out on foot (with every

fourth man holding the horses in the rear) to locate their opponents and test their strength. Mounted units were held

in reserve to exploit any weakness that might be uncovered. At Aldie, and again at Middleburg, the Confederates relied

heavily on the tactic of dismounting sharpshooters behind stone walls and ambushing the Federals at point-blank range.

Federal commanders had limited tactical options and tried them all. They could extend their lines beyond the Confederates’

flanks and maneuver them out of position; they could mass a deadly concentration of artillery fire to drive the defenders

off; or they could bull their way up the road in a mounted assault. Even if momentarily successful, they could expect

an equally determined mounted counterattack, and the momentum could swing abruptly to the other side. While there was

much dismounted fighting, these battles featured a great deal of what can only be called stubborn brawling—the kind

of stirrup-to-stirrup mounted combat with saber and pistol that took a deadly toll of men and mounts.

As the war dragged on, the saber charges of Brandy Station and of Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville became

increasingly rare as units of both sides forsook cold steel for carbines and repeating rifles. But in June 1863, the

thunderous mounted assault embodied all the dash and chivalry that yet adhered to the cavalry arm. See also Pennsylvania Civil War History.

Advance to:

Sources: National Park Service; Civil War Trust; civilwar.org; Head, James W. History and Comprehensive

Description of Loudoun County Virginia. Washington, DC: Parkview Press, 1908. OCLC 1837578; O'Neill, Robert F. The Cavalry

Battles of Aldie, Middleburg and Upperville: Small But Important Riots, June 10–27, 1863. Lynchburg, VA: H.E. Howard,

1993. ISBN 1-56190-052-4; Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole

Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

|