|

Battle of Appomattox Court House

Commonwealth of Virginia Civil War History

Battle of Appomattox Court House

Other Names: Appomattox

Location: Appomattox County

Campaign: Appomattox Campaign (March-April 1865)

Date(s): April 9, 1865

Principal Commanders: Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant [US]; Gen. Robert E. Lee [CS]

Forces Engaged: Armies

Estimated Casualties: 700 total (27,805 Confederate soldiers

paroled)

Result(s): Union victory

Introduction: The beginning of the end of the Confederacy. Early

on April 9, the remnants of Confederate Maj. Gen. John Brown Gordon’s corps and Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry (nephew

of Gen. Robert E. Lee) formed line of battle at Appomattox Court House. Gen. Robert E. Lee determined to make one last

attempt to escape the closing Union pincers and reach his supplies at Lynchburg. At

dawn the Confederates advanced, initially gaining ground against Sheridan’s cavalry. The arrival of Union infantry,

however, stopped the advance in its tracks. Lee’s army was now surrounded on three sides. Lee surrendered to Grant later

in the day on April 9, making this the final engagement of the war in Virginia.

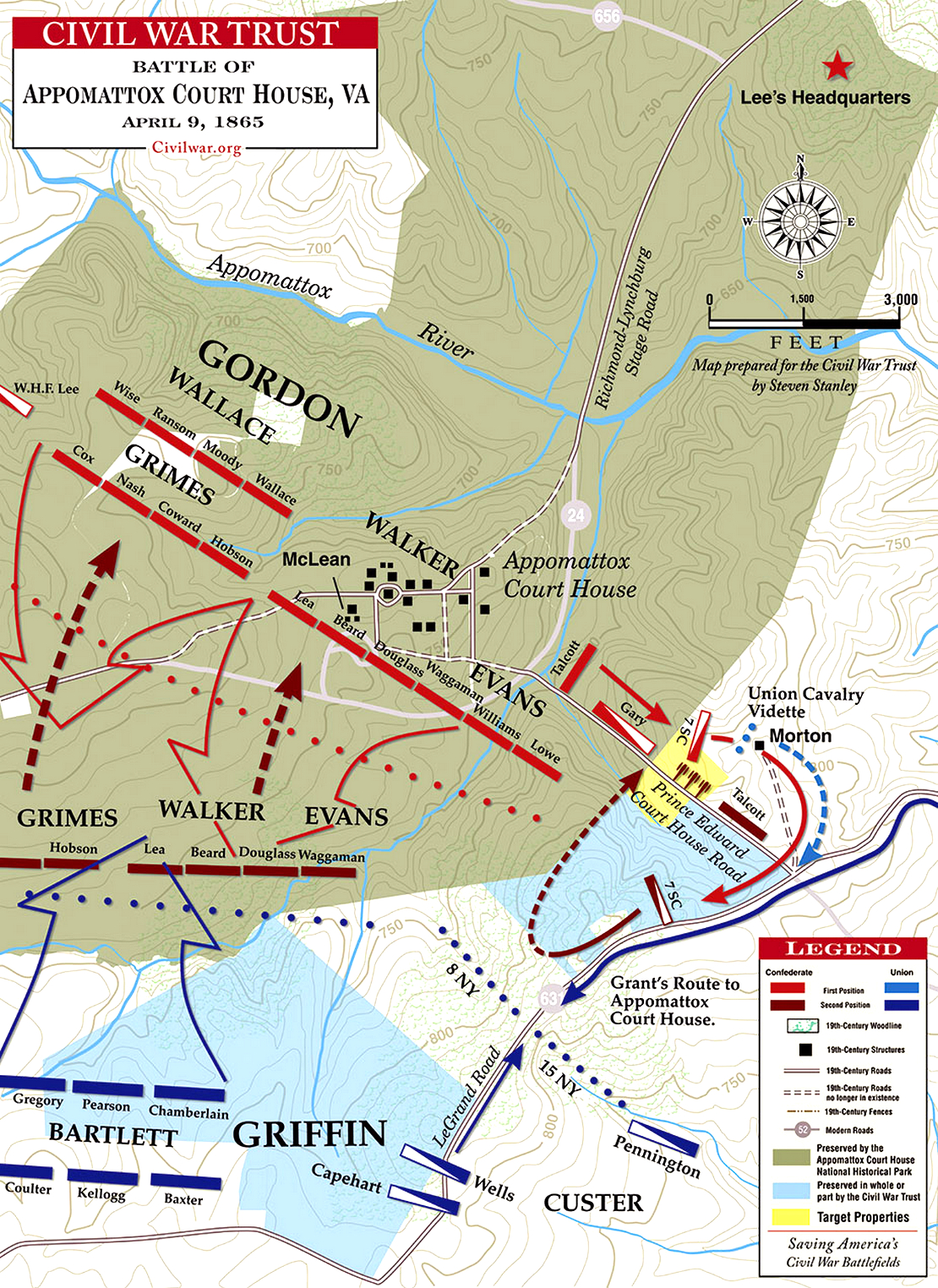

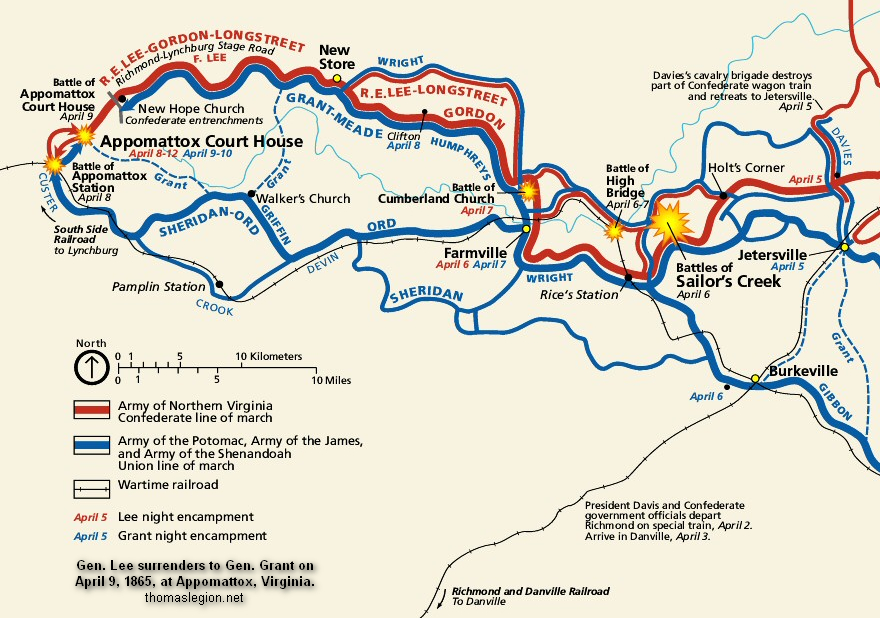

| Battle of Appomattox Court House Map |

|

| Appomattox Court House Battlefield Map |

Summary: Approximately 9,000 men under Gordon and Fitzhugh

Lee deployed in the fields west of the village before dawn and waited. The attack, launched before 8:00 a.m. and led

by General Bryan Grimes of North Carolina, was initially successful. The outnumbered Union cavalry fell back, temporarily

opening the road. But it was not to be. Union infantry began arriving from the west and south, completing Lee’s

encirclement. Meanwhile, Longstreet’s troops were being pressed from the rear near New Hope Church, three miles

to the east. General Ulysses S. Grant’s goal of cutting off and destroying Lee’s army was close at hand.

Bowing to the inevitable, Lee ordered his troops to retreat through the

village and back across the Appomattox River. Small pockets of resistance continued until flags of truce were sent out

from the Confederate lines between 10:00 and 11:00 a.m. Rather than destroy his army and sacrifice the lives of his soldiers

to no purpose, Lee decided to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia.

Although not the end of the war, the surrender of Lee’s Army of Northern

Virginia set the stage for its conclusion. Through the lenient terms, Confederate troops were paroled and allowed to

return to their homes while Union soldiers were ordered to refrain from overt celebration or taunting. These measures

served as a blueprint for the surrender of the remaining Confederate forces throughout the South. Although a formal peace

treaty was never signed by the combatants, the submission of the Confederate armies ended the war and began the long and difficult

road toward reunification.

| Appomattox Court House Battlefield Map |

|

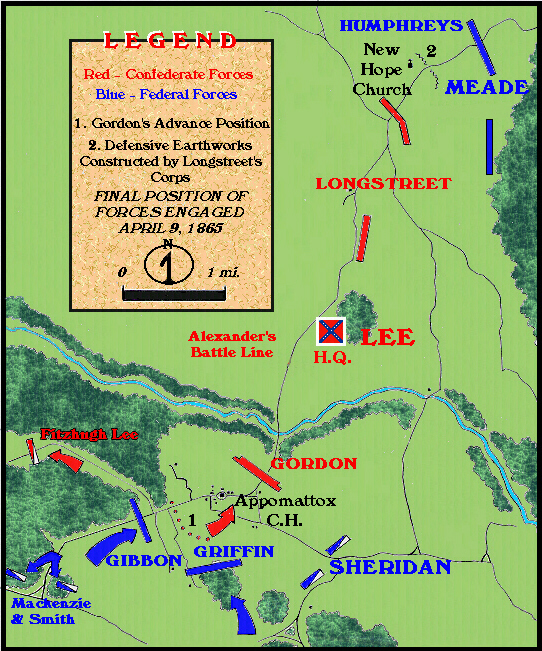

| Union and Confederate Positions on April 9, 1865 |

(Right) Movement of Union and Confederate armies on April 9, during the

final fighting of the Civil War in Virginia. By the 9th, Lee's forces had dwindled to some 28,000 while Grant's army numbered

more than 100,000 -- and was growing.

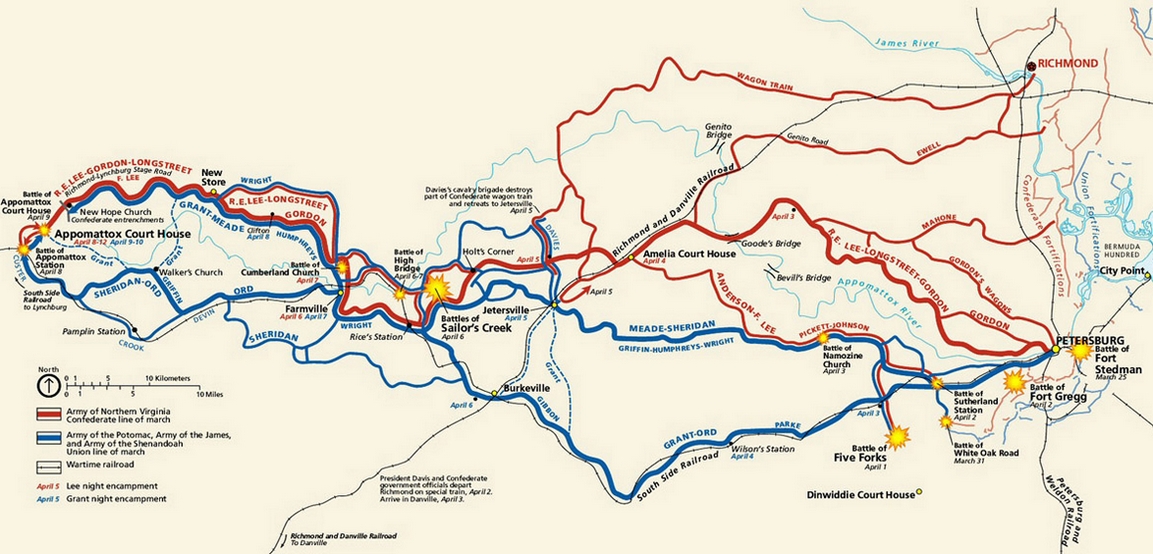

Appomattox Campaign: The Appomattox Campaign was a series

of Civil War battles fought March 29 – April 9, 1865, in Virginia that concluded with the surrender of General Robert

E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia to the Union Army (Army of the Potomac, Army of the James and Army of the Shenandoah) under

the overall command of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. In the following eleven weeks after Lee's surrender, the Civil

War ended as other Confederate armies surrendered and Confederate government leaders were captured or fled the country.

As the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign (also known as the Siege of Petersburg)

ended, Lee's army was outnumbered and exhausted from a winter of trench warfare over an approximately 40 mile front, numerous

battles, disease, hunger and desertion. Grant's well-equipped and well-fed army, meanwhile, was growing in strength.

On March 29, 1865, the Union Army began an offensive that stretched and broke the Confederate defenses southwest of Petersburg

and cut their supply lines to Petersburg and the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Union victories at the Battle

of Five Forks on April 1, 1865 and the Third Battle of Petersburg, often called the Breakthrough at Petersburg, on April 2,

1865, opened Petersburg and Richmond to imminent capture. Lee ordered the evacuation of Confederate forces from both Petersburg

and Richmond on the night of April 2–3 before Grant's army could cut off any escape. Confederate leaders also fled

west from Richmond that night.

The Confederates marched west, heading toward Danville, or Lynchburg, Virginia,

as an alternative. Lee planned to resupply his army at one of those cities and march southwest into North Carolina where he

could unite his army with the Confederate army under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. Grant's arm pursued Lee's fleeing Confederates

relentlessly. During the next week, the Union troops fought a series of battles with the persistent Confederates, and cut

off or destroyed the Rebel's supplies and blocked their paths to the south and ultimately to the west. On April 6, 1865, the

Confederate Army suffered a significant defeat at the Battle of Sailor's Creek, Virginia, where they lost about 7,700 men

killed and captured and an unknown number wounded. Nonetheless, Lee continued to move the remainder of his battered army to

the west. Soon cornered, short of food and supplies and outnumbered by more than 3-to-1, Lee surrendered the Army of Northern

Virginia to Grant on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

| Civil War Appomattox Campaign Map |

|

| Battle of Appomattox Court House and Surrender of Army of Northern Virginia, April 9, 1865 |

| Surrender of Lee to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse |

|

| Battle of Appomattox Court House, Virginia, April 9, 1865 |

Battle: At dawn on April 9, the Confederate Second

Corps under Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon attacked Sheridan's cavalry and quickly forced back the first line under

Brevet Brig. Gen. Charles H. Smith. The next line, held by Brig. Gens. Ranald S. Mackenzie and George Crook ,

slowed the Confederate advance. Gordon's troops charged through the Union lines and took the ridge, but as they reached the

crest they saw the entire Union XXIV Corps in line of battle with the Union V Corps to their right. Lee's cavalry saw these

Union forces and immediately withdrew and rode off towards Lynchburg. Ord's troops began advancing against Gordon's corps

while the Union II Corps began moving against Lt. Gen. James Longstreet 's corps to the northeast. Colonel Charles Venable

of Lee's staff rode in at this time and asked for an assessment, and Gordon gave him a reply he knew Lee did not want to hear:

"Tell General Lee I have fought my corps to a frazzle, and I fear I can do nothing unless I am heavily supported by Longstreet's

corps." Upon hearing it Lee finally stated the inevitable: "Then there is nothing left for me to do but to go and see General

Grant and I would rather die a thousand deaths."

Many of Lee's officers, including Longstreet, agreed that surrendering the

army was the only option left. The only notable officer opposed to surrender was Longstreet's chief of artillery, Brig. Gen.

Edward Porter Alexander , who predicted that if Lee surrendered then "every other [Confederate] army will follow suit".

At 8:00 a.m., Lee rode out to meet Grant, accompanied by three of his aides.

Grant received Lee's first letter on the morning of April 9 as he was traveling

to meet Sheridan. Grant recalled his migraine seemed to disappear when he read Lee's letter, and he handed it to his assistant

Rawlins to read aloud before composing his reply:

"General, Your note of this date is but this moment, 11:50 A.M. rec'd.,

in consequence of my having passed from the Richmond and Lynchburg road. I am at this writing about four miles West of Walker's

Church and will push forward to the front for the purpose of meeting you. Notice sent to me on this road where you wish the

interview to take place."

Grant's response was remarkable in that it let the defeated Lee choose the

place of his surrender. Lee received the reply within an hour and dispatched an aide, Charles Marshall, to find a suitable

location for the occasion. Marshall scrutinized Appomattox Court House, a small village of roughly twenty buildings that served

as a waystation for travelers on the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road. Marshall rejected the first house he saw as too dilapidated,

instead settling on the 1848 brick home of Wilmer McLean. McLean had lived near Manassas Junction during the First Battle

of Bull Run , and had retired to Appomattox to escape the war.

With gunshots still being heard on Gordon's front and Union skirmishers

still advancing on Longstreet's front, Lee received a message from Grant. After several hours of correspondence between Grant

and Lee, a cease-fire was enacted and Grant received Lee's request to discuss surrender terms.

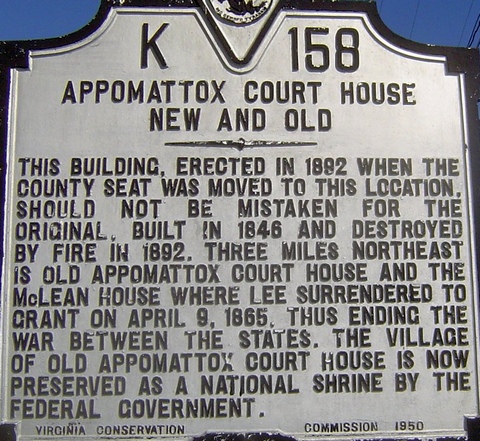

| Appomattox Court House History |

|

| McLean House Parlor |

(About) Panoramic image of the reconstructed parlor of the McLean House.

Ulysses S. Grant sat at the simple wooden table on the right, while Robert E. Lee sat at the more ornate marble-topped table

on the left. Much of the original furniture and decorations were purchased or taken by attending Union officers following

the surrender.

Surrender: Gen. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia maintained strong

morale throughout the Appomattox Campaign, but was greatly reduced by attrition, insomuch that it now numbered scarcely

28,000. Lee army was shrinking by the day. Grant's combined army was a behemoth, and although it had swelled to over

100,000, fresh troops were arriving daily. By surrendering, Lee had saved his starving, fledgling army from further disaster.

By now, more than any other time, it was apparent to all that the Confederacy was indeed The Lost Cause.

The signing of the surrender documents occurred in the parlor of the house

owned by Wilmer McLean on the afternoon of April 9. Dressed in an immaculate uniform, Lee waited for Grant to arrive.

Grant, whose headache had ended when he received Lee's note, arrived at the courthouse in a mud-spattered uniform—a

government-issue sack coat with trousers tucked into muddy boots, no sidearms, and with only his tarnished shoulder straps

showing his rank. It was the first time the two men had seen each other face-to-face in almost two decades. Suddenly overcome

with sadness, Grant found it hard to get to the point of the meeting and instead the two generals briefly discussed their

only previous encounter, during the Mexican-American War. Lee brought the attention back to the issue at hand, and Grant offered

the same terms he had before:

"In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst.,

I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men

to be made in duplicate. One copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such officer or

officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of

the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their

commands. The arms, artillery and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me

to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each

officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe

their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside."

The terms were as generous as Lee could hope for; his men would not be imprisoned

or prosecuted for treason. Officers were allowed to keep their sidearms. In addition to his terms, Grant also allowed the

defeated men to take home their horses and mules to carry out the spring planting and provided Lee with a supply of food rations

for his starving army; Lee said it would have a very happy effect among the men and do much toward reconciling the country.

The terms of the surrender were recorded in a document hand written by Grant's adjutant Ely S. Parker, a Native American

of the Seneca tribe, and completed around 4 p.m., April 9. Lee, upon discovering Parker to be a Seneca allegedly remarked,

"It is good to have one real American here." Parker replied, "Sir, we are all Americans." As Lee left the house and rode away,

Grant's men began cheering in celebration, but Grant ordered an immediate stop. "I at once sent word, however, to have it

stopped," he said. "The Confederates were now our countrymen, and we did not want to exult over their downfall," he said.

Custer and other Union officers purchased from McLean the furnishings of the room Lee and Grant met in as souvenirs, emptying

it of furniture. Grant soon visited the Confederate army, and then he and Lee sat on the McLean home's porch and met with

visitors such as Longstreet and George Pickett before the two men left for their capitals.

| Appomattox Court House Surrender Meeting |

|

| Grant (L) meeting with Lee (R) in parlor at McLean House |

| Battle of Appomattox Court House |

|

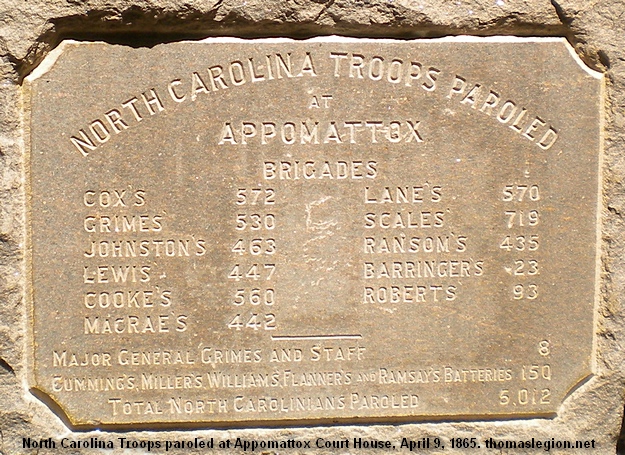

| North Carolina Troops Paroled at Appomattox, April 9, 1865 |

(Left) The North Carolina Monument was erected in 1905 by veterans from

that state on the site where the last volley fired by the Army of Northern Virginia took place. The monument recognizes and

eulogizes the North Carolina troops throughout the war, proclaiming them "First at Bethel, farthest to the front at Gettysburg

and Chickamauga, and last at Appomattox." (Right) On April 9, 1865 after four years of Civil War, approximately 620,000 deaths

and over 1,000,000 wounded, General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to Lieutenant General

Ulysses S. Grant, at the home of Wilmer and Virginia McLean in the rural town of Appomattox Court House, Virginia. General

Lee arrived at the McLean home shortly after 1:00 p.m. followed a half hour later by General Grant. The meeting lasted approximately

an hour and a half.

On April 10, Lee gave his farewell address to his army. On April 12, a formal

ceremony marked the disbandment of the Army of Northern Virginia and the parole of its officers and men, effectively ending

the war in Virginia. About 28,000 Confederate soldiers had stacked their arms. The Appomattox Roster lists approximately

26,300 men who surrendered. This number does not include the 7,700 who were captured at Sailor's Creek three days earlier.

This event triggered a series of surrenders across the south, signaling the end of the war.

The terms agreed to by General Lee and Grant and accepted by the Federal

Government would become the model used for all the other surrenders which shortly followed. On April 26th General Joseph Johnston

surrendered to Major General W. T. Sherman near Durham, North Carolina (now Bennett Place State Historical Park); on May 4th

General Richard Taylor, the son of 12th President of the United States, Zachary Taylor, surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama;

on June 2nd General Edmund Kirby Smith surrendered the Confederate Department of the Trans Mississippi to Major General Canby;

and on June 23rd General Stand Watie surrendered Confederate Cherokee Indian forces in Oklahoma.

Aftermath: While General George Meade reportedly

shouted that "it's all over" upon hearing the surrender was signed, Grant was aware that only a single army had given up.

Roughly 175,000 Confederates remained in the field, but none of them had commanders of the same caliber as Lee. Many

of these were scattered throughout the South in garrisons while the rest were concentrated in three major Confederate commands.

Just as Porter Alexander had predicted, as news spread of Lee's surrender other Confederate commanders realized that the strength

of the Confederacy was gone, and decided to lay down their own arms.

Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's army in North Carolina, the most threatening of

the remaining Confederate armies, surrendered to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman at Bennett Place in Durham, North Carolina

on April 26, 1865. The 98,270 Confederate troops that laid down their weapons (the largest surrender of the war) marked the

virtual end of the conflict. General Taylor surrendered his army at Citronelle, Alabama in early May, followed by General

Edmund Kirby Smith surrendering the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department on May 26, 1865 near New Orleans,

Louisiana. Upon hearing about General Lee's surrender, Nathan Bedford Forrest, "The Wizard of the Saddle", also surrendered,

reading his farewell address on May 9, 1865, at Gainesville, Alabama. Brig. Gen. Stand Watie surrendered the last sizable

organized Confederate force on June 23, 1865, in Choctaw County, Oklahoma.

There were several more small battles after Lee's surrender. The Battle

of Palmito Ranch on May 12–13, 1865, is commonly regarded as the final land battle of the war. Commander James

Iredell Waddell surrendered the CSS Shenandoah on November 6, 1865, at Liverpool , Great Britain. Lee never forgot

Grant's magnanimity during the surrender, and for the rest of his life would not tolerate an unkind word about Grant in his

presence.

| Appomattox Campaign |

|

| Battle of Appomattox Court House, April 9, 1865 |

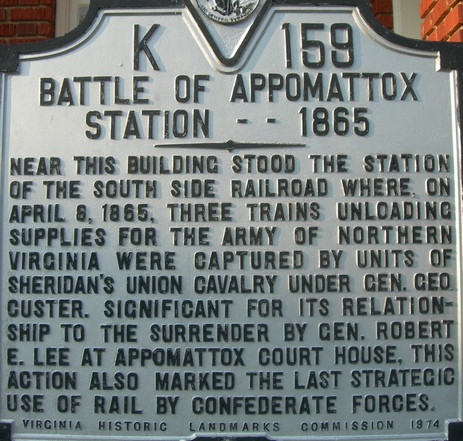

| Appomattox Campaign |

|

| Battle of Appomattox Station, April 8, 1865 |

| Appomattox Campaign Map |

|

| Enhanced view of Appomattox Court House, VA. |

Analysis: The location of Appomattox usually

reminds us of Lee surrendering to Grant at the Court House. But two battles were actually fought here before the surrender.

The location was also host to the last fighting of the Civil War in Virginia, and it was this place that put

into motion a series of events, including the assassination of President Lincoln.

On April 8, Union cavalry attacked Confederate artillery at Appomattox Station.

The next morning, Confederate troops attempted to break out, but were halted by Union infantry and cavalry in the battle of

Appomattox Court House. The Battle of Appomattox Court House, fought on the morning of April 9, 1865, was one of the last

battles of the Civil War, and it was the final engagement of General Robert E. Lee 's Army of Northern Virginia before it

surrendered to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Lee, having abandoned the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, after

the ten-month Siege of Petersburg, retreated west, hoping to join his army with the Confederate forces in North Carolina.

Union forces pursued and cut off the Confederate retreat at the village of Appomattox Court House, but Lee launched an attack

to break through the Union force to his front, assuming the Union force consisted entirely of cavalry. When he realized that

the cavalry was supported by two corps of Union infantry, he had no other option but to surrender.

Lee's signing of the surrender documents occurred in the parlor of the house

owned by Wilmer McLean on the afternoon of April 9. On April 12, a formal ceremony marked the disbandment of the Army

of Northern Virginia and the parole of its officers and men, effectively ending the war in Virginia. This event triggered

a series of surrenders across the south, signaling the end of the war.

The terms of the surrender would parole officers and enlisted men but required that all Confederate military

equipment be relinquished. The discussion between the generals then drifted into the prospects for peace, but Lee, once again

taking the lead, asked Grant to put his terms in writing. When Grant finished, he handed the terms to his former adversary,

and Lee -- first donning spectacles used for reading-- quietly looked them over. When he finished reading, the bespectacled

Lee looked up at Grant and remarked "This will have a very happy effect on my army." Lee asked if the terms allowed his men

to keep their horses, for in the Confederate army men owned their mounts. Lee explained that his men would need these animals

to farm once they returned to civilian life. Grant responded that he would not change the terms as written (which had no provisions

allowing private soldiers to keep their mounts) but would order his officers to allow any Confederate claiming a horse or

a mule to keep it. General Lee agreed that this concession would go a long way toward promoting healing. Grant's generosity

extended further. When Lee mentioned that his men had been without rations for several days, the Union commander arranged

for 25, 000 rations to be sent to the hungry Confederates. After formal copies of the surrender terms, and Lee's acceptance,

had been drafted and exchanged, the meeting ended.

In a war that was marked by such divisiveness and bitter fighting, it is remarkable that it ended so simply.

Grant's compassion and generosity did much to allay the emotions of the Confederate troops. As for Robert E. Lee, he realized

that the best course was for his men to return home and resume their lives as American citizens. Before

he met with General Grant, one of Lee's officers (General E. Porter Alexander) had suggested fighting a guerilla war, but

Lee had rejected the idea. It would only cause more pain and suffering for a cause that was lost. The character of both Lee

and Grant was of such a high order that the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia has been called "The Gentlemen's Agreement."

After Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia formally surrendered at Appomattox Court House on April

12, 1865, the news spread quickly throughout the Northern states. Upon hearing the report, Actor John Wilkes Booth told

Louis J. Weichmann, a friend of John Surratt, and a boarder at Mary Surratt's house, that he was done with the stage and that

the only play he wanted to present henceforth was Venice Preserv'd. Weichmann did not understand the reference, however.

Venice Preserv'd is about an assassination plot. With the Union Army's capture of Richmond and Lee's surrender, Booth's

old scheme to kidnap President Lincoln was no longer feasible, and he changed his plot to assassination.

The previous day, April 11, Booth was in the crowd outside the White House when Abraham Lincoln gave an

impromptu speech from his window. When Lincoln stated that he was in favor of granting suffrage to the former slaves, Booth

declared that it would be the last speech Lincoln would ever make. On the morning of Good Friday, April

14, 1865, Booth went to Ford's Theatre to get his mail, and while there he was told by John Ford's brother that President

and Mrs. Lincoln accompanied by Gen. and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant would be attending the play Our American Cousin at

the theatre that evening.

Lt. Gen. Grant was to attend the play with Lincoln, but opted to visit his children in New Jersey shortly

prior to Booth's performance. At Ford's Theatre on April 14, Booth walked up from behind and at

about 10:13 pm, aimed directly at the back of Lincoln's head and fired at point-blank range, mortally wounding the President.

Efforts to revive Lincoln failed and he was pronounced dead at 7:22 am, April 15, 1865.

(Sources and related reading below.)

Sources: Library of Congress; National Park

Service; Appomattox Court House National Historic Park; Civil War Trust, civilwar.org; Official

Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Bearss, Edwin C., with Bryce A. Suderow. The Petersburg Campaign. Vol. 2, The

Western Front Battles, September 1864 – April 1865. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014. ISBN 978-1-61121-104-7;

Blair, Jayne E. The Essential Civil War: A Handbook to the Battles, Armies, Navies and Commanders. Jefferson, NC and London:

McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006. ISBN 978-0-7864-2472-6; Calkins, Chris. The Appomattox Campaign, March 29 – April

9, 1865. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1997. ISBN 978-0-938-28954-8; Davis, Burke. To Appomattox: Nine April Days, 1865.

New York: Eastern Acorn Press reprint, 1981. ISBN 978-0-915992-17-1. First published New York: Rinehart, 1959; Evans, Clement

A., ed. Confederate Military History: A Library of Confederate States History. Volume 5. Capers, Ellison; South Carolina.

12 vols. Atlanta: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. OCLC 833588. Retrieved January 20, 2011; Greene, A. Wilson. The Final

Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2008.

ISBN 978-1-57233-610-0; Humphreys, Andrew A., The Virginia Campaign of 1864 and 1865: The Army of the Potomac and the Army

of the James. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1883. OCLC 38203003; Jamieson, Perry D. Spring 1865: The Closing Campaigns

of the Civil War. Lincoln, NE and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-8032-2581-7; Kennedy, Frances H.,

ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5; Longacre, Edward

G. The Cavalry at Appomattox: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations During the Civil War's Climactic Campaign, March 27 –

April 9, 1865. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8117-0051-1; Marvel, William. Lee's Last Retreat: The

Flight to Appomattox. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8078-5703-8;Randol, Alanson Merwin.

Last Days of the Rebellion. The Second New York cavalry (Harris' Light) at Appomattox Station and Appomattox Court House,

April 8 and 9, 1865. Alcatraz Island, CA: 1886. OCLC 58763899. Originally published: Presidio of San Francisco, 1883; Salmon,

John S., The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide, Stackpole Books, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8117-2868-3; Schaff, Morris.

The Sunset of the Confederacy. Boston: J. W. Luce and Company, 1912. OCLC 1851090; Sheridan, P. H. "The Last Days of the Rebellion"

in The North American Review. Vol. 137, No. 320 (Jul., 1883), p. 13. Published by: University of Northern Iowa; Starr, Steven.

The Union Cavalry in the Civil War: The War in the East from Gettysburg to Appomattox, 1863–1865. Volume 2. Baton Rouge:

Louisiana State University Press, 2007. Originally published 1981. ISBN 978-0-8071-3292-0; Tremain, Henry Edwin. The Last

Hours of Sheridan's Cavalry. New York: Bonnell, Silvers and Bowers, 1904. Reprint of 1871–1872 publication. OCLC 4368467;

Trudeau, Noah Andre. "Out of the Storm: The End of the Civil War, April–June 1865. Boston, New York: Little, Brown and

Company, 1994. ISBN 978-0-316-85328-6; Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders, Louisiana State University

Press, 1964, ISBN 0-8071-0822-7; Winik, Jay. April 1865: The Month That Saved America. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. ISBN

978-0-06-089968-4.

|