|

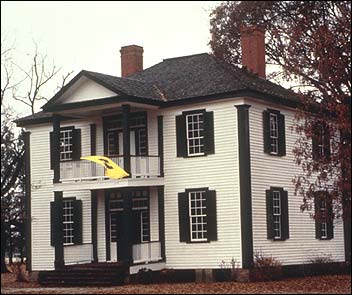

| The Bentonville Historic Harper House |

|

| Harper House was a hospital during the Battle of Bentonville |

The three day Battle of Bentonville produced a total of 4,133 casualties.

Union losses were 1,527, with 194 killed, 1,112 wounded, and 221 missing and captured. Confederate casualties

totaled 2,606, with 239 killed, 1,694 wounded, and 673 missing and captured. Many of the wounded found

themselves in a field hospital set up by Sherman's Fourteenth Army Corps. Its surgeons, searching for a safe location, chose

the modest two-story farm home of John and Amy Harper, and wounded began streaming to this makeshift medical facility within

minutes of its establishment a mile from the chaotic front lines. Throughout March 19 and 20, Federal surgeons at the Harper

House treated a total of 554 men, both Union and Confederate. Without the benefit of antibiotics to stop infection, doctors

amputated shattered arms and legs to prevent gangrene from claiming their patients' lives. Despite the screams of the wounded,

the piles of severed limbs, and the stench of blood and chloroform (an anesthetic used by Union surgeons) that pervaded the

Harper House, the family refused to leave their home during this time.

March 19, 1865, dawned soft and balmy in central North Carolina. A brass band

played the hymn "Old Hundred." The hymn's tranquil strains reminded the 30,000 men on the Left Wing of Maj. Gen. William T.

Sherman's Union army group that it was Sunday, while blossoming fruit trees called to mind quiet homes and families far away.

Many of the soldiers looked forward to the end of the war, which now seemed imminent.

But the idle thoughts of a Sunday morning exploded as the Federals approached

the farming community of Bentonville. Just outside of town 20,000 tattered Confederates, the remainder of a once-powerful

army, attacked the Union troops. Dreams of joyous reunions were soon replaced by the carnage of war, and men who had marched

to the front now lay wounded on the battlefield.

Four years earlier, at the beginning of the war, these men might have remained,

untreated, on the battlefield for days. At the First Battle of Manassas in 1861, for example, many Union doctors fled in fear and those who stayed found themselves without adequate supplies or

ambulances for their patients. As the war progressed and casualties mounted, however, military surgeons became more adept

at caring for wounded. By the Battle of Bentonville, one of the last major engagements of the Civil War, the United States

Army Medical Department had developed an effective system for operating field hospitals and an ambulance corps. This improved

organization was typical of the advances in logistics that helped the North's war effort. Bentonville's Harper House was quickly

overwhelmed by both Union and Confederate wounded; the historic Harper House reflected the typical Civil War battlefield's

Medical Treatment for the Wounded.

| Battle of Bentonville Casualties Map |

|

| Civil War Battle of Bentonville Casualties Map |

Sources: National Park Service; Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site

Recommended Reading: Gangrene and Glory: Medical Care during the American Civil War (University

of Illinois Press). Description: Gangrene and Glory covers practically every aspect of the 'medical related issues'

in the Civil War and it illuminates the key players in the development and advancement of medicine and medical treatment.

Regarding the numerous diseases and surgical procedures, Author Frank Freemon discusses what transpired both on and off the

battlefield. The Journal of the American Medical Association states: Continued below...

“In Freemon's vivid account, one almost sees the pus,

putrefaction, blood, and maggots and . . . the unbearable pain and suffering.” Interesting historical

accounts, statistical data, and pictures enhance this book. This research is not limited to the Civil War buff, it is a must

read for the individual interested in medicine, medical procedures and surgery, as well as some of the pioneers--the surgeons

that foreshadowed our modern medicine.

Recommended Reading:

Doctors in Gray: The Confederate Medical Service (339 pages) (Louisiana State University Press). Description: Horace Herndon Cunningham has created a comprehensive history of the "Confederate medical services in

the Civil War." Cunningham explains in great detail the many afflictions and circumstances that befell Confederate soldiers

and ultimately resulted in medical treatment by the Confederate doctor. Ironically, his research reflects that the majority

of the ill and wounded soldiers who died had expired due to a burgeoning and developing medical system. Continued below...

Medical advancements, however, had progressed from primitive to slightly better by the end of the conflict.

Cunningham further explains that while the Confederate doctors did the best that they could with their resources and shortcomings,

there were some exceptional doctors who aided in the advancement of both medicine and medical treatment.

|