|

Battle of Cloyd's Mountain

Cloyd's Mountain and the Civil War

Battle of Cloyd's

Mountain, Virginia

Other Names: Battle of Cloyd's Farm

Location: Pulaski County, Virginia

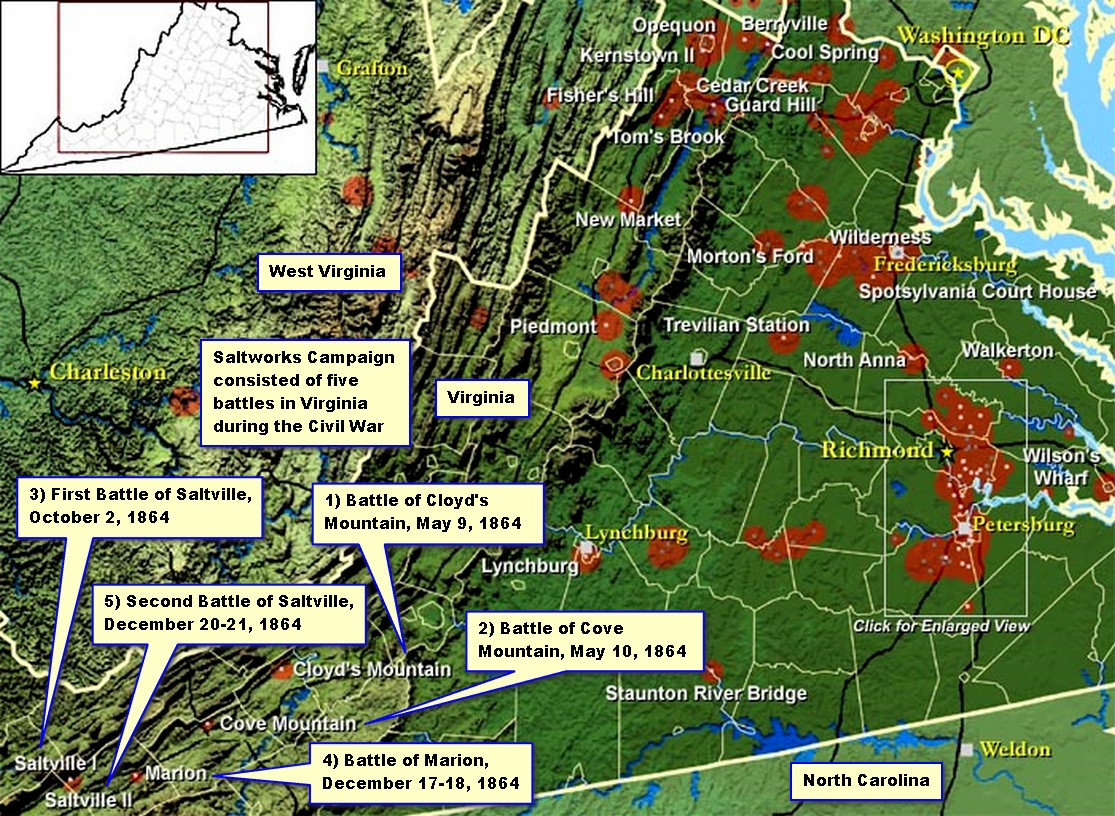

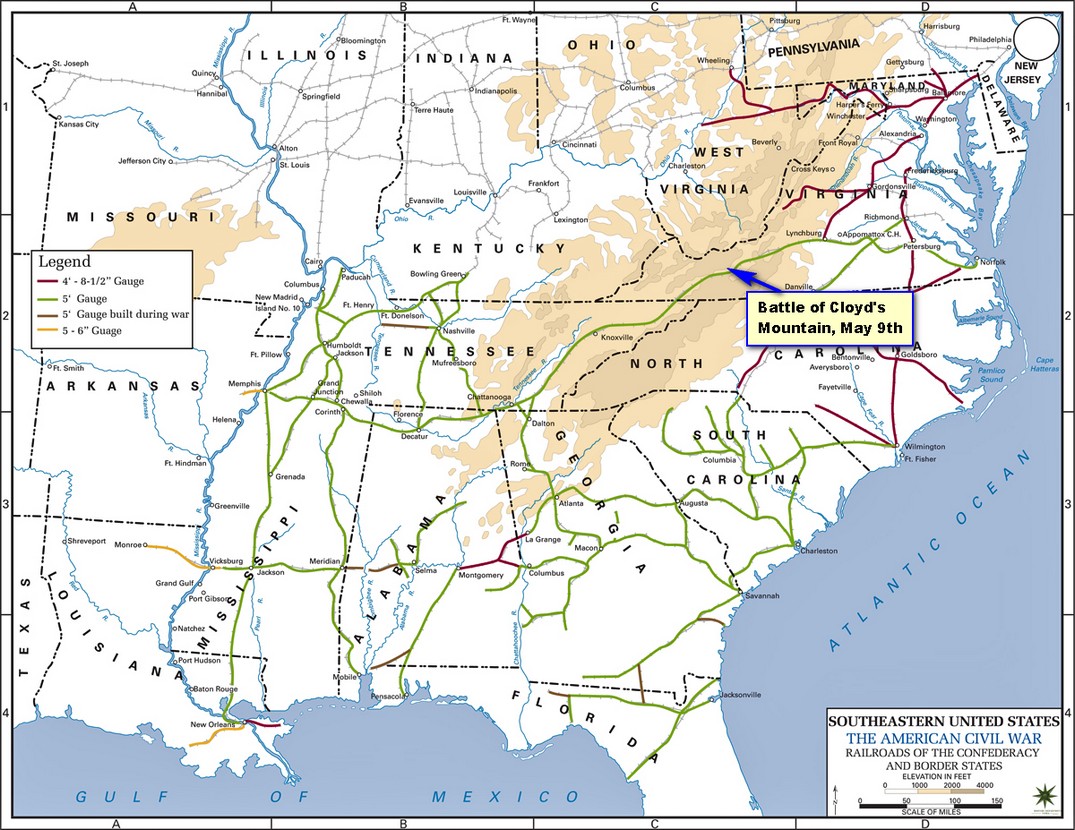

Campaigns: Crook-Averell Raid on the Virginia & Tennessee

Railroad (May 1864); Virginia Saltworks Campaign (May-December 1864)

Date(s): May 9, 1864

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. George Crook [US]; Brig. Gen.

Albert Jenkins [CS]

Forces Engaged: (US 6,155; CS 2,400)

Casualties: 1,226 total (US 688 total/108k/508w/72c)

(CS 538 total/76k/262w/200c)

Result(s): Union victory

Introduction: The Battle of Cloyd's Mountain, fought on May 9,

1864, was the first of five battles fought during the Virginia Saltworks Campaign. Salt was vital to life and war, and the

railroad at Cloyd's Mountain needed to be destroyed if the Union force was to be successful in pressing an

assault on the Confederacy's major producer of salt at nearby Saltville. Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins, who practiced

law and represented Virginia in the United States Congress until the conflict began, had assumed command of the

Department of Western Virginia on May 5, 1864, and before he had time to settle at the department's headquarters

at Dublin, he was in receipt of a dispatch stating that a large body of Union troops was en route to his area and

that his department was to engage and deny the enemy of its objectives. Lt. Gen. Grant, who later served as U.S. President, ordered

Brig. Gen. George Crook (known mainly for later exploits during the Indian Wars) in April 1864 to advance his division and

cut the Virginia and Tennessee railroad, located at Dublin. By cutting the region's only rail lines, the Confederacy

couldn't move troops quickly to support and reinforce its thin gray line of defense in southwestern Virginia and East

Tennessee. Brig. Gen. William Averell (graduate of West Point), meanwhile, marched his division in the direction of Saltville

with the principal objective of destroying its saltworks, but receiving reports that the Confederates were informed of

his intentions and had a large force well-entrenched there, he focused on destroying the region's railroads and assisting Crook.

The armies contested this ground for seven hours with infantry, cavalry, and artillery, including fierce hand-to-hand

fighting for an hour. While Lee's drubbing of Grant at the Wilderness overshadowed the contest, the battle continues to be

overlooked by the more recognized engagements of the Civil War, but it was a struggle for life and death to the

more than 1,200 casualties that had fought at the place known as Cloyd's Mountain.

| Cloyd's Mountain Civil War History |

|

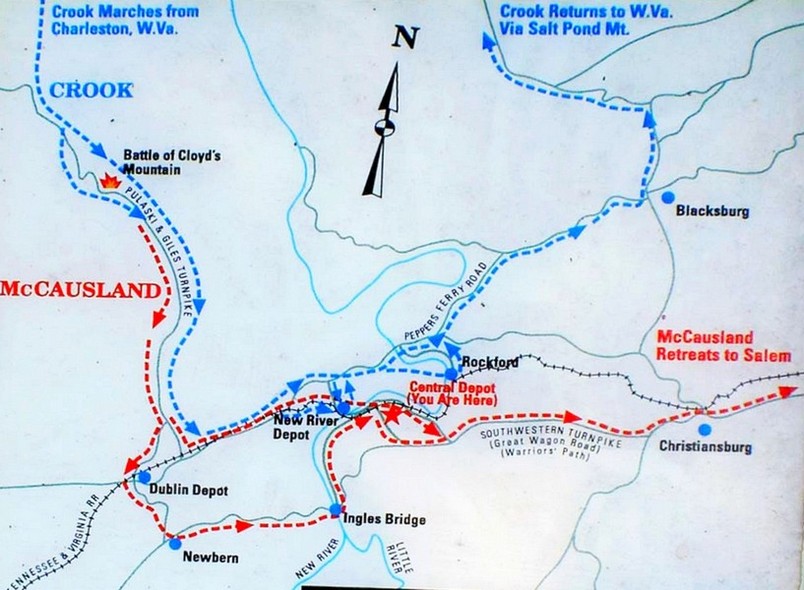

| Map of the Battle of Cloyd's Mountain and the Saltworks Campaign |

| Vital Civil War railroads of Virginia |

|

| Civil War era railroad destruction between Bristow Station and the Rappahannock. |

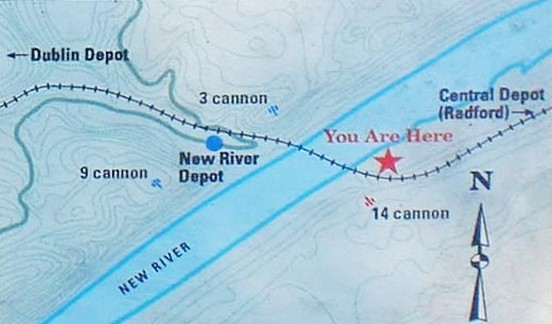

| Cloyd's Mountain and New River Bridge Civil War |

|

| The New River Bridge, near Dublin, spanned more than 700 feet. |

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain History. |

|

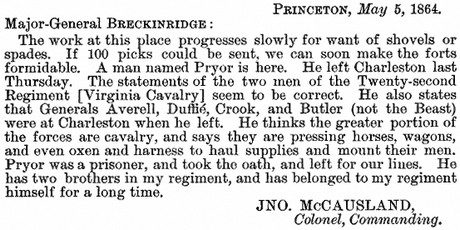

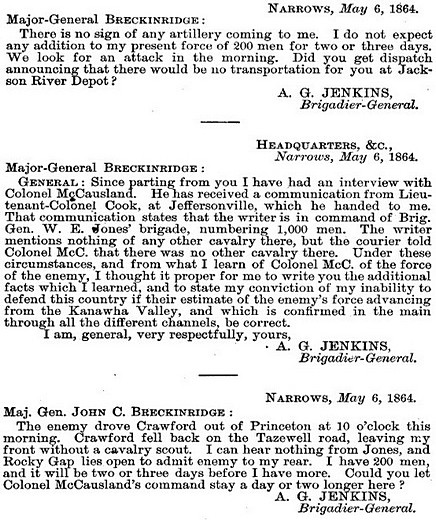

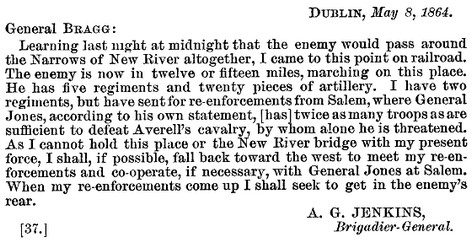

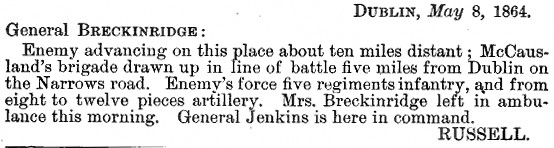

| McCausland warned of imminent Union assault on Saltville. Official Records. |

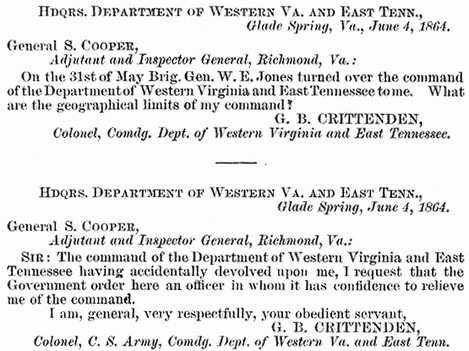

Summary: Just days prior to the Union advance into

southwestern Virginia, Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, commanding Department of Southwestern Virginia, was ordered by General

Robert E. Lee to move most of his department to Lynchburg in an attempt to strengthen his flank. Breckinridge would order

Brig. Gen. Alfred Jenkins to assume command of the skeleton department during his absence, and he would direct Brig. Gen.

William "Grumble" Jones, commanding Department of East Tennessee, to coordinate with Jenkins a joint defense of

the sparsely defended front. Plagued with a hastily formed command that consisted of only a few hundred men until

just days prior to the fight, the Confederates also lacked leadership during its ill-fated defense. In an attempt

to protect such a large swath of the State of Virginia with only a token force, the Rebel army would also be troubled by poor

leadership during Breckinridge's absence. Jenkins, who was infuriated by Jones' refusal to answer a single dispatch,

predicted, that with the intentional division of forces by Jones, he would soon die while defending the

ground.

Union Brig. Gen. George Crook, having received orders from Lt. Gen.

U.S. Grant in early April of 1864, moved his division of 6,155 soldiers on a raid into southwestern Virginia and encountered

a hastily assembled Confederate force under Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins at Cloyd’s Mountain. With the exception

of some Kentucky men, the Confederate brigade consisted mainly of Virginians, including an unknown number of home guards. While

fighting on May 9th was furious and hand-to-hand, Colonel D. Howard Smith, commanding John Hunt Morgan's dismounted

cavalry, arrived near the end of the battle as the Confederates were retreating. Performing rearguard for the beaten Rebels,

Smith's men fired at will for about one hour checking each of several Union cavalry advances before retiring from the

scene. Leaving 200 men which were captured by Crook, the Confederate command had been forced to withdrawal after

the seven hour fight. Casualties were high for the size of the forces engaged: Union 11%, Confederate 23%. Jenkins, aged 33,

mortally wounded, was captured by the enemy, who, in an effort to save the Virginian, amputated his shattered left arm

but to no avail as the young brigadier died on May 20th while in a field hospital. Col. John A. McCausland, the

second officer, assumed command of the brigade and was appointed brigadier general on May 24, 1864. See also Union and Confederate Casualty Reports for Battle of Cloyd's Mountain.

After destroying depots, several important railroad bridges and much

of the region's tracks, including the 700-foot New River bridge whose piers secured the only railroad connecting Virginia

and Tennessee, Crook's force joined with Averell's division on May 15th, who had been repulsed in a four

hour attempt to rout the Confederate force at Wytheville, and the united column withdrew to Meadow

Bluff.

At Cloyd's Mountain, Brig. Gen. Jones had refused to follow

Maj. Gen. Breckinridge's orders instructing him to cooperate and defend the front with acting commander Brig.

Gen. Jenkins, which served only to embolden the enemy while further dividing an already thin gray line of defense. Whereas

Jones commanded the Department of East Tennessee, he had moved the majority of his command, some 4,500 cavalry, with

him into neighboring southwestern Virginia for the battle. But concerning Jenkins, Jones utterly refused to coordinate

a defense or to send a single horseman to his aid. As the former was commanding a force of merely 2,400 men, Brig. Gen. Crook unleashed

6,000 veteran troopers on his position. Jones, known as "Grumble" for his out of control temper, meanwhile, continued

to lead his own autonomous command, which he always believed was independent of the host Department of

Western Virginia.

Although the Rebel army remained in confusion during Breckinridge's

leave, the division of its forces was the primary cause for the defeat at Cloyd's. Union troops maintained high

morale, however, as they trekked and swept Confederate soldiers from the fields of southwestern Virginia. Two future U.S. presidents also served and fought while in the Union Army

during the battle: Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley. Hayes would serve as 19th President, succeeding U.S. Grant

in office, and McKinley, having survived the bloodiest war in U.S. history, would serve as 25th President only to fall

victim to an assassin's bullet, which would result in his Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt, assuming the presidency.

History: "I hope to have God on my side, but I must have

Kentucky," said Lincoln as Civil War confronted the nation three years earlier. This was truly the brothers'

fight involving many regiments from West Virginia and Kentucky, both being Border States. Although Lincoln was born in Kentucky, he would not carry the state during

either of his elections. The Bluegrass State was known as home to First Lady Mary Todd and her cousin John C. Breckinridge,

but Mary had watched six of her seven brothers enlist in the Confederate Army. The western most portion of Virginia had seceded

from the Commonwealth of Virginia and formed the State of West Virginia just one year prior on June 20, 1863, causing no love

lost between the two states.

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant would become commander of the Union Army on March

9, 1864, and subsequently implement his plan to defeat the rebellion in the Southern states. To execute his grand strategy,

Grant would unleash a coordinated offensive by moving several Union armies throughout Virginia during the spring

of 1864. Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler would move on Richmond up the James River from Fortress Monroe in the Hampton Roads area.

General Franz Sigel would push southward in the Shenandoah Valley toward Staunton. Grant would join the Army of the Potomac

in the field and move from Washington, D.C., and march toward the Confederate capital which sat some 100 miles

to the south.

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain |

|

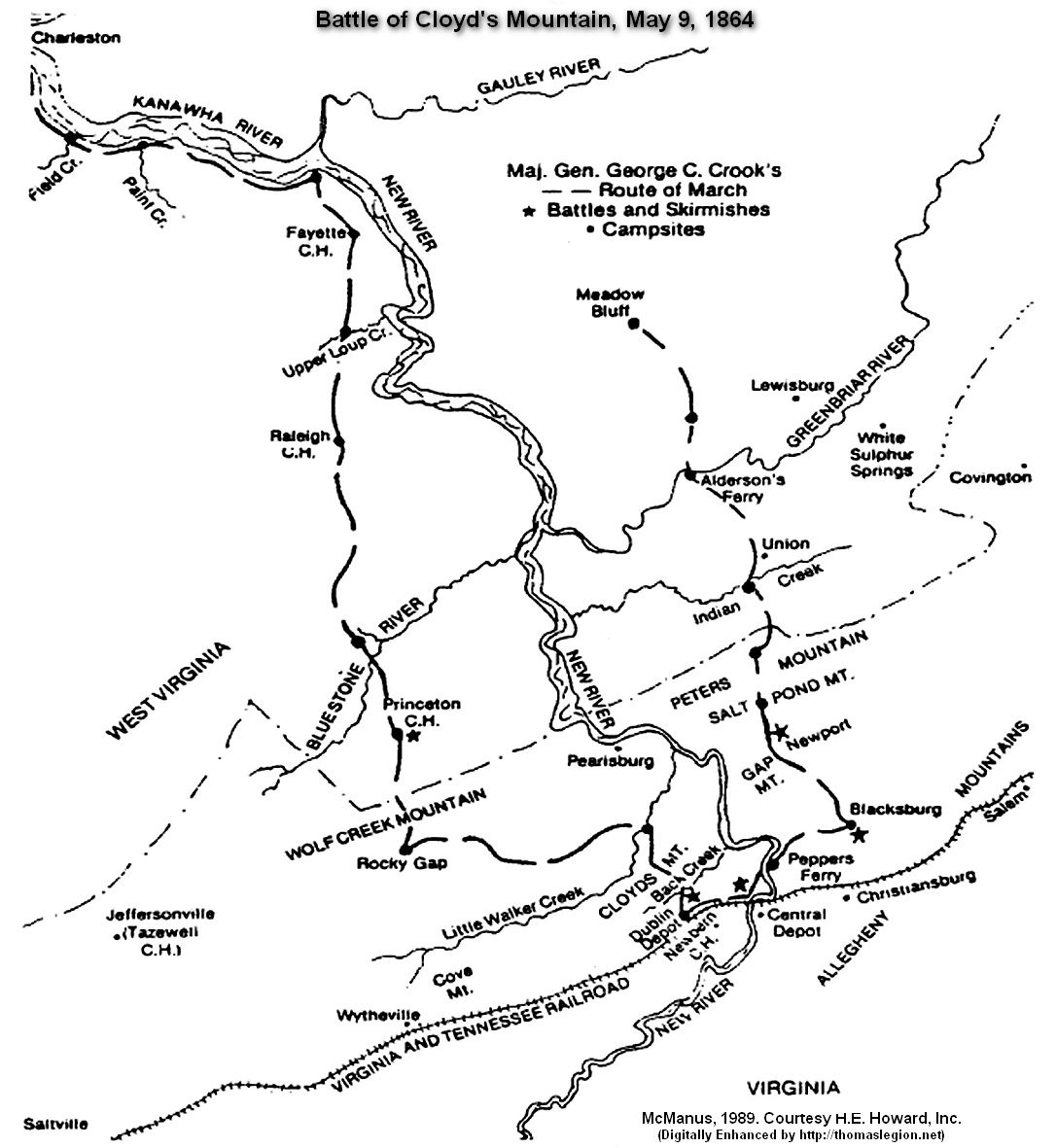

| 1864 Route and Battles in Southwestern Virginia |

The last major component of Grant's grand strategy in Virginia was to move

Brig. Gen. George Crook's Army of the Kanawha from Charleston, WV, through the Allegheny Mountains and destroy the New River

Bridge and cut as much of the vital Virginia and Tennessee railroad in the New River Valley. To date, the Union command had

made several attempts to strike the same targets in southwestern Virginia, only to be thwarted. In 1861, Federal commanders

in West Virginia considered burning the New River Bridge. In 1862 and 1863, a number of ill-conceived and aborted attempts

to rip the region's railroad by Union forces took place. Contrary to earlier attempts, Crook's 1864 Kanawha Expedition was

timed perfectly. Gen. Robert E. Lee's army was now being pressed in northern Virginia, and as a result he strengthened

his Army of Northern Virginia by ordering the much needed brigades in southwestern Virginia to his endangered left flank

at Lynchburg in an effort to destroy the Federal forces advancing from the Shenandoah Valley. If Crook was successful,

however, he too would continue to Lynchburg, and there join Federal forces advancing from the valley, and thus isolate Lee

completely from desperately needed resources arriving from the west.

Brig. Gen. George Crook (West Point class of '52) assumed command

of the Kanawha Division in February 1864. At the time only a few regiments remained from the original Kanawha Division which

had fought at South Mountain and the division was officially designated the Second Infantry Division in the Department of

West Virginia. The division of 6,155 soldiers comprised three brigades commanded respectively by colonels Rutherford Hayes,

Carr B. White and Horatio G. Sickel. While West Virginia Union regiments were dispersed throughout the three brigades, the

original Ohio regiments were divided between Hayes and White and two Pennsylvania regiments were added with the arrival of

Colonel Sickel. Lt. Gen. Grant, General of the Union Army, would have Crook lead his division into action at the battle

of Cloyd’s Mountain and then join Maj. Gen. David Hunter’s army for the battle of Lynchburg. Although Maj.

Gen. Franz Sigel had initially received Grant's orders to move Crook into southwestern Virginia to command the Kanawha

Expedition, it was Maj. Gen. David Hunter who would replace Sigel, because of his poor performance at New Market, as commander

of the Department of West Virginia on May 15th.

On May 1, 1864, at Charleston, West Virginia, Brig. Gen.

Crook, commanding, ordered Brig. Gen. William W. Averell to move his cavalry command into southwestern Virginia

by a different route as to confuse the enemy as to his objectives and to lessen the footprint of his already large force.

Averell's army consisted of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Duffie (fought in Crimean War) and Colonel Schoonmaker (future

Medal of Honor recipient), numbering in all 2,079 officers and men, and 400 of the 5th and 7th West Virginia Cavalry. The

orders he received from Crook were to move against and destroy the saltworks at Saltville, Virginia. On May

2nd, Crook marched his Kanawha Division out of Kanawha Valley and headed south with the objective of destroying

the Virginia and Tennessee railroad.

On the following day, May 2nd, Crook marched his division in the direction

of Dublin with nine infantry regiments, seven cavalry regiments, and 15 artillery pieces, a force of 6,155 men organized

into three brigades. The West Virginia countryside was beautiful that spring, but the mountainous terrain made the march a

difficult undertaking. The way was narrow and steep, and spring rains slowed the march as tramping feet churned the roads

into mud. In places, Crook's engineers had to build bridges across wash-outs before the army could advance. The column reached

Fayette later on May 2nd, and then passed through Raleigh Court House and Princeton. In just six days, on the night of May

8th, the division would camp at Shannon's Bridge, Virginia, 10 miles north of Dublin.

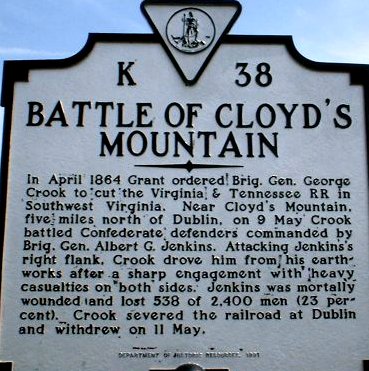

| Civil War Virginia Historical Marker |

|

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain Historical Marker |

| Official Records for Battle of Cloyd's Battle |

|

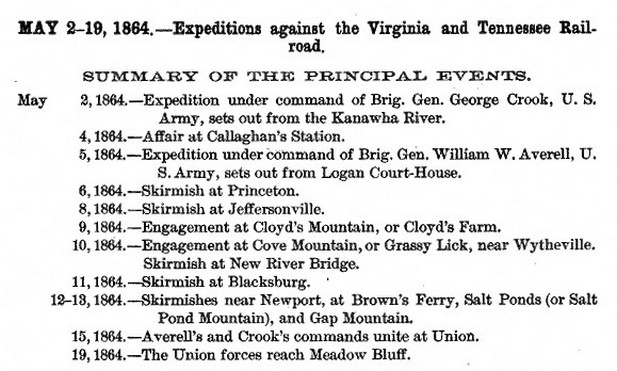

| Summary of Principal Events for Expedition against Virginia and Tennessee Railroad |

Confederate Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge (former Vice President and cousin

to First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln) had assumed command of the Department of Western Virginia on Feb. 25, 1864, relieving

Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones. Breckinridge had been receiving regular updates from his scouts on the movements of the

Kanawha force and Averell's division, but it wasn't until May 2nd that the former U.S. Vice President had some conviction

about the plan of the enemy.

While the Department of Western Virginia had already been wanting by

May of 1864, Breckinridge would be ordered by Gen. Robert E. Lee to collect a force, which amounted to three brigades

totaling 4,000 men, roughly forty-percent of his entire department, and proceed to Stanton immediately.

Breckinridge would later move much of the Department of Western Virginia into the fighting in the Shenandoah.

Whereas Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones commanded the Department

of East Tennessee, his impressive cavalry brigade, numbering some 4,000 troops, was operating in southwestern

Virginia. On May 4th, Gen. Bragg ordered Jones, who had assumed commandership of East Tennessee two days prior on

May 2nd, to return his brigade to East Tennessee, but after Maj. Gen. Breckinridge received the report, he

sought Lee to countermand the orders immediately. While Lee did rescind Bragg's orders, he issued a set of own: Breckinridge

was to mass as many units as possible and come to the assistance of Lee.

Breckinridge would initially assemble the brigades of Echols (1,600

infantry), Wharton (900), and McCausland (1,500), and two batteries from the 13th Virginia Artillery (12 artillery

pieces) to accompany him to Stanton on May 5th, but soon he would receive

dispatches from several sources informing him that Crook's main body was on collision course with his greatly reduced

department at Dublin. He would reluctantly instruct McCausland's brigade to assist Jenkins for only

one day. The command had been operating as a thin gray line of defense in southwestern Virginia, but now, stripped

of practically all of

its infantry, it was ordered to withstand the imminent assault of Crook at all hazards. While Imboden's and Vaughn's

brigades would also be joining Breckinridge, many other units would soon follow him to the Shenandoah Valley, including

McCausland's brigade.

On May 5th, Maj. Gen. Breckinridge

instructed Brig. Gen. William E. Jones about the importance of protecting west of the New River, and stressed that it

was uncovered and depends on you. Brig. Gen. Jenkins is to communicate with you, and you are to confer with him, concluded

Breckinridge. West of the New River was a large area, so large that one brigade still couldn't sufficiently respond to an

advancing army, unless it was by rail, but during this time the forces of Crook and Averell were tearing sections of track

from the region's only line, being the Virginia and Tennessee railroad. The same track would also prove

to be detrimental to reinforcements striving to arrive and assist the outnumbered Confederates

at Dublin. If a feint was made to the west at greater Abington, for example, it would easily move Jones' brigade

some 100 miles from Jenkins' position.

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain Civil War History |

|

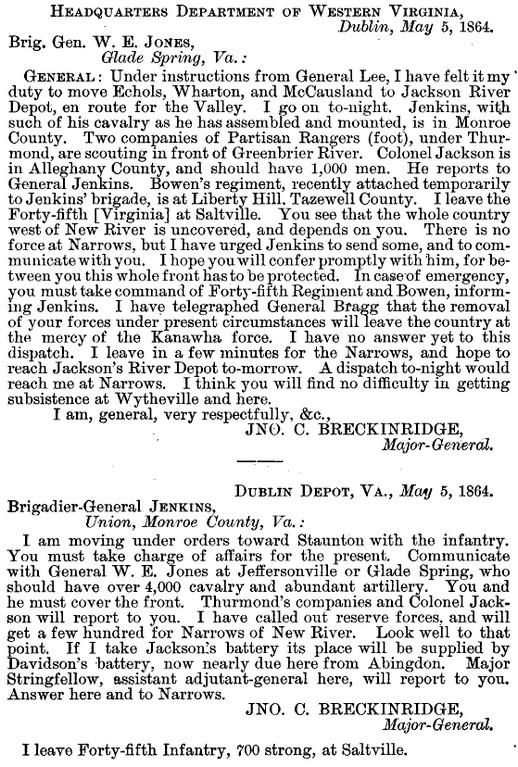

| Breckinridge gives temporary command of department to Jenkins. |

| Official Records for Battle of Cloyd's Mountain |

|

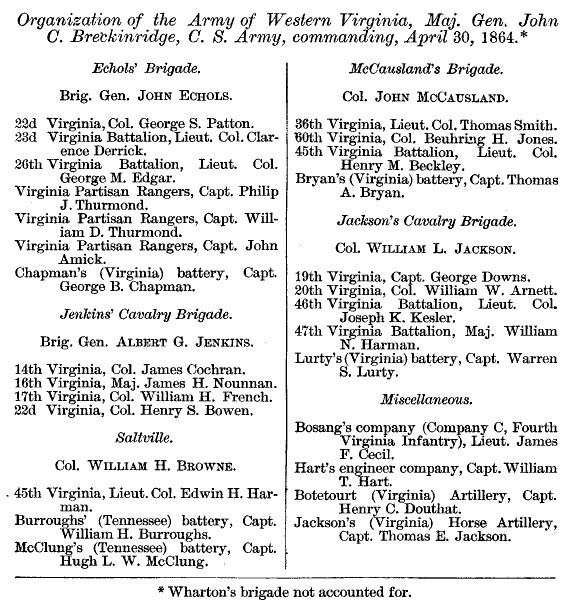

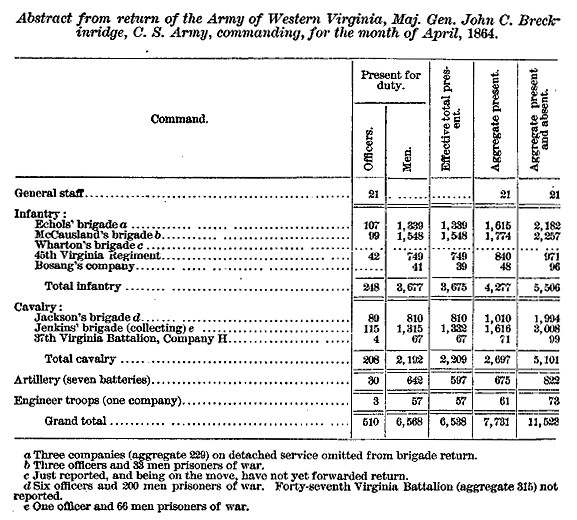

| Final adjusted returns for Army of Western Virginia before battle of Cloyd's. Official Records |

Breckinridge, upon being ordered

to Stanton by Lee, hastily instructed Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins, a former U.S Congressman, to assume

temporary command of the Department of Western Virginia on May 5th, and he also directed both Jenkins and Brig. Gen. William

"Grumble" Jones (West Point class of '48) to coordinate and cover the front. As Breckinridge moved quickly under Lee's

orders, he had failed to dictate orders or at the very least forward a circular informing his department of

their interim commander during his absence. In his dispatch to Jones on the 5th, Breckinridge stated clearly that

the department's subordinate units would be reporting to Jenkins, but because he failed to officially communicate to

the command his delegation of authority, it would result in a lack of leadership and the inability to effectively command

and control the department. Jenkins, who would be leading the scant Confederate defense against the advancing Union army

of some 6,000 veteran soldiers, would personally have to inform all the regiments, companies, and batteries of his

generalship. The Union main body would press the Confederate position in just four days, but the present malaise would

soon cause very poor responses and utter confusion among the Rebel units as the Federal army moved on its headquarters

at Dublin. Jenkins would have unwavering support from Brig. Gen. John McCausland, because, unlike the rest of the

department, he would soon receive personal orders instructing him to move his brigade and report directly to Jenkins,

now commanding Department of Western Virginia. By

retaining McCausland's brigade of 1,500 Virginians, and rallying another 900 troops by Jenkins, the recently appointed

commander would be able to field 2,400 Confederates against the 6,000 strong division led by Brig. Gen. Crook.

Lee had very tough decisions

to make on which front to protect, during what was now an obvious war of attrition, and although the Dept. of Western

Virginia was already stretched, the Confederate capital of Richmond remained priority one. Absent, Breckinridge would

continue sending several dispatches informing Jenkins of Crook's movements.

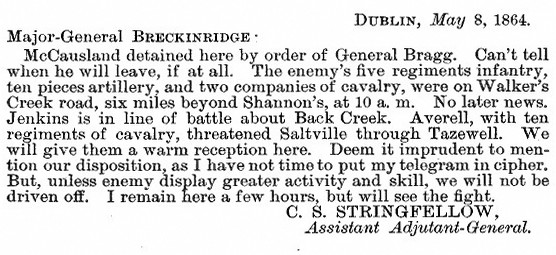

The Confederates at Dublin had received

a dispatch on the evening of May 2nd, warning of a planned Union assault on Saltville and the area's lead mines and railroads.

Subsequent reports from scouts reiterated the size and movements of the Crook's large Union force. By May 5th, Breckinridge,

knowing that an engagement was nigh, now had orders from Lee to move as much of the Department of Western Virginia to Stanton

and join the Army of Northern Virginia's efforts in repulsing the Federal invasion on his left flank.

| How to prepare for battle |

|

| McCausland prepares defenses |

In a dispatch dated May 5th 10 a.m., Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins, commanding, had

been informed by Captain J. Crawford, at Rocky Gap, that the enemy had pushed his cavalry company, which had ben operating

as scouts, off the top of a nearby mountain, and that from his position he could see three Union regiments moving

into the area. Just one hour later, five regiments advancing, and more behind them, was the report from the captain. Crawford

had sent a detachment toward Narrows while the rest of his company fell back to the Wytheville Road, which was the road

that led to both Saltville and Dublin. Jenkins was in Union, Monroe County, on the morning of the 5th with his plucky

force of 200, and upon receiving the news from Crawford, Jenkins marched and arrived at Narrows in an effort to harass the

enemy. Because Narrows, just inside Virginia, by way of West Virginia, hosted the main road to Dublin, Jenkins was aware

that the large Federal contingent was on a collision course and closing in on his rather unprotected headquarters

on the New River. On the morning of the 6th, Crawford's scouts had been driven out of Princeton, thus exposing

the rear of Jenkins' scant force by way of Rocky Gap.

To escape the trap by the Union army, Jenkins would be forced to

fall back to the Alamo at Dublin in hopes that reinforcements would come to his aid in what he knew was an imminent fight. Jenkins,

with much urgency, would send three dispatches to Breckinridge describing his plight: no artillery, only 200 men to protect

from here to Dublin, expect attack in the morning, Crawford pushed out of Princeton, no reinforcements are coming to my assistance,

and knowing the size of the enemy, it is my conviction that my present command of 200 is unable to halt the enemy.

Three dispatches had been sent to Breckinridge during the day of the 6th, but Jenkins had yet to receive a single reply.

Another telegram arrived and was placed in the hand of Breckinridge on the 6th,

but this one reported that Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan was to leave East Tennessee immediately and move his

force and support Breckinridge's command in southwestern Virginia. Morgan, under Special Orders, No. 102, had already

been transferred to Breckinridge's command on May 2nd by the direction of Secretary of War James Seddon, but the transfer

was expedited with Crook and Averell now moving toward the region.

The Rebel scouts were forced back from Jenkins' front during the day

of May 6th, exposing his position to an unchecked advance, so he sent an urgent telegram to Breckinridge requesting

the former U.S. Vice President to allow McCausland to remain and assist for another day or two. He had hoped

to receive a rapid response, for time too had now become an enemy. In a second telegram to Breckinridge, dated

later on the same day, he reminded the major-general that he had neither artillery nor cavalry, there

are no scouts, and that he needed horses to ascertain the position of the enemy. I have heard nothing from

Jones. My current force is 200, and I expect an imminent attack, continued Jenkins.

Though Breckinridge had left the day prior for Stanton, his directive

to Jones to coordinate a defense with Jenkins didn't appear to make any difference. For want of troops, the 200 which

mustered that day served only as a reminder to the new commander of the perilous condition of the now hollow department.

| Official Records, Union and Confederate Armies |

|

| Final adjusted returns for Army of Western Virginia before battle of Cloyd's. Official Records. |

| Official Records for Battle of Cloyd's Mountain |

|

| Jenkins sent several telegrams to Breckinridge on May 6, 1864. Official Records. |

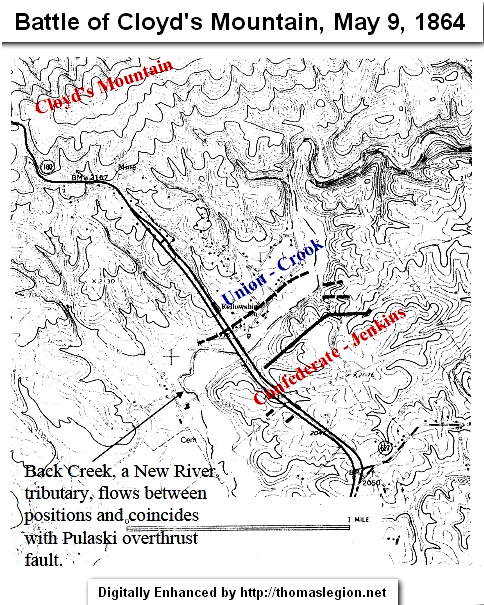

| Cloyd's Mountain Battlefield Map |

|

| Civil War Cloyd's Mountain Battle Map |

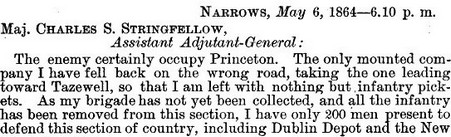

On May 6th Jenkins sent a telegram that was to be read by Gen.

Braxton Bragg who was at the Confederate capital of Richmond.

On the evening of May 6th, Jenkins had contemplated his position and the

fact that he must, at the very least, have McCausland if his department is to have a fighting chance of defending Dublin and

the New River bridge. He had also conveyed his conviction to Breckinridge

by stating that the main body of the enemy would be attacking his faithful 200 by morning, but there was

no response. The utter silence to his three telegrams was interpreted by Jenkins as a no, a slight, to his request,

and he knew that McCausland was moving his brigade toward Stanton in the morning. Jenkins recalled the many reports indicating the size and movements of the

enemy as well as his multi-faceted dilemma with the likes of Brig. Gen. William Jones, who being present in the region but

AWOL in cooperation, and that the department he had inherited from Breckinridge was neither heard from nor seen. Feeling

helpless, Jenkins sent an urgent telegram to the Assistant-Adjutant General, Major Charles S. Stringfellow.

He characterized the plight of the

beleaguered department in one harrowing telegram to Major Stringfellow by stating that he was only in possession

of 200 men total, yet he had the responsibility to defend from Dublin to the New River bridge. He stressed the fact

that though Breckinridge had instructed both he and Brig. Gen. William E. Jones to cooperate and control the front jointly,

Jones had not sent one man nor responded to his requests to do so. Lacking cooperation from within the department was one

thing, but Jenkins had been placed in a position that under ordinary circumstances would have already been difficult.

He had so few troops to rally against the approaching Federal division, no men nor reply from Jones, no reply

from Breckinridge, which was perceived as a no answer, and no superior to intervene during the present crisis. Command

and control was utterly absent, so in the discussed letter to Stringfellow, Jenkins, believing he was left no other

option, asked the assistant-adjutant to forward the telegram directly to Gen. Braxton Bragg himself. Bragg was one of

only a handful of full-generals, meaning he was equal in rank to General Robert E. Lee, but though subordinate by both date

of rank and command responsibility.

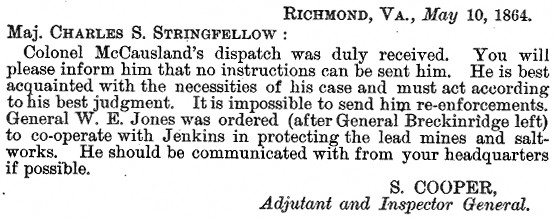

Maj. Stringfellow forwarded the telegram to Gen. Bragg, and by doing so

Breckinridge replied at 1 a.m. on May 7th, and said that Brig. Gen. John Morgan is to report directly to Jenkins.

Next, Breckinridge instructs his Assistant Adjutant-General, Maj. Johnston, to telegram Jenkins instructing him to retain

McCausland. While Breckinridge initially made a concession stating that McCausland could assist Jenkins for a day, Bragg reiterated

in a second telegram that McCausland was to assist Jenkins until the danger has passed.

| Confederate army at Cloyd's from Official Records |

|

| After battle report stating fighting strength of Confederates at Cloyd's Mountain |

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain Civil War History |

|

|

| Jenkins states his condition clearly |

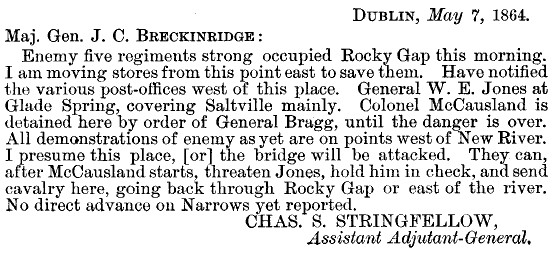

While the enemy was approaching, Colonel

John McCausland, commanding McCausland's brigade, was at Dublin on the morning of May 7th and prepared to move his 1,500

men to join Breckinridge at Stanton. On May 7th, prior to the arrival of transportation, a courier from Brig.

Gen. Jenkins, commanding, informed McCausland that the two of them were ordered by Maj. Gen. Breckinridge (former U.S.

Vice President under James Buchanan) to halt Crook's advance. The combined forces of Jenkins and McCausland totaled 2,400

men, mainly of infantry. Jenkins, known as a successful cavalry commander, then made quick decisions regarding strategy.

He knew the area well and proceeded to move his much smaller force on May 5th to the familiar summit position

on nearby Cloyd's Mountain, less than five miles from Dublin depot, and prepare for the fight. The battle would be fought

from the base to the crest of the mountain, with artillery and the main body engaging from atop, and with the small

cavalry and infantry force receiving the full brunt of the advancing Union division below. Cloyd's Mountain would host

seven hours of murderous fire of grape, canister, and musketry, as well as one hour of eye to eye, close range combat.

The ground was protected by strong natural and manmade defensive works,

and for the Union juggernaut to approach Jenkins' men and force the fight, it would have to traverse a course of

rugged terrain, brushy ridges, deep gullies, and streams while under relentless fire from two artillery batteries on

the summit. Next, the Federals would need to ascend the ridge, which in places inclined to sixty degrees, and withstand

more than one thousand small arms discharging in their direction. To breach the crest, one also had to navigate formidable

breastworks and a species of cheval-de-frise made of rails which had been inverted.

Brig. Gen. William E. Jones, meanwhile, enjoyed a stout 4,000-man

cavalry brigade that would soon thwart Brig. Gen. Averell's 2,000 horsemen during its attempt to move Jones off Cove

Mountain. Jenkins would therefore need to lead his 2,400 defenders himself while commanding the Alamo of Cloyd's.

Though confronted with the full brunt of the approaching 6,000 veterans under the command of Crook, Jenkins was a

veteran cavalryman who was not averse to great risk, for he had raided the likes of Kentucky, West Virginia, and

even Ohio and enjoyed the spoils of war. As the 33 year old brigadier would soon dismount one more time in the State

which he had represented in the U.S. Congress, he would do so with the understanding that he had dismounted for

the last time.

Jenkins did send several reports to Breckinridge leading up to the battle

requesting immediate reinforcements, and now he was patiently awaiting John Hunt Morgan's army. His command would

not be further enlarged save for Morgan who was due on the scene at any moment, so Jenkins hoped. He now held scouting

reports indicating the strength of the enemy to be from 6,000 to 9,000 soldiers, so he made one final appeal to

the major-general by stating that unless he received additional troops, he believed that his small command of 2,400 would

be dispersed when pressed. Breckinridge would never respond. Brig. Gen. George Crook's Union command, which had already

slugged through the region virtually unopposed while tearing up much of the Virginia and Tennessee railroad, was

now veering and placing its sights on the bull's eye Jenkins.

| Official Records of the Civil War |

|

| Stringfellow named both locations that Crook would attack |

| History of Cloyd's Mountain, Virginia |

|

| Second telegram informing Breckinridge that McCausland stays |

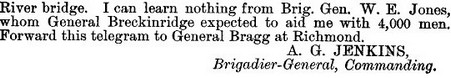

On May 7th, however, Brig. Gen. "Grumble" Jones sent one of his few dispatches

during the looming offensive to Major Stringfellow informing him that his 4,000 strong force was at Glade Spring

and that Saltville was now sufficiently garrisoned. But while Jones, only 10 miles from the salt facilities, was

some 70 miles west of Cloyd's Mountain, he qualified the distance to the assistant-adjutant by stating that cavalry

could readily reinforce, succor as he called it, either the New River bridge or Saltville quickly. Jones, believing that

Crook would soon open the battle at or near the New River bridge, espoused the position that Averell would

likely use the opportunity to move through his area, thinking that Jones had indeed joined Jenkins for the engagement, and then

press the action and destroy both the token force and salt production at Saltville. But though in textbook style he had accurately

predicted Averell's move on the saltworks, his location would prove costly for Jenkins, who had yet to receive a

single dispatch from "Grumble" Jones.

Stringfellow was no stranger to Jones, because two months prior, March 9,

1864, there was much confusion as to which department had the responsibility of protecting Saltville itself. Richmond,

having been sought by the departments of East Tennessee and Western Virginia, was asked to make a decision

on the matter, and Stringfellow, knowing Jones well, said to Gen. Sam Cooper that he had no knowledge of the distinct settlement

of this question, but he emphasized that Jones had always believed that the safety of Saltville was his personal

responsibility. Jones would point to a telegram that he had received from the honorable Secretary of War, which Stringfellow

would soon acknowledge, stating that the protection of the saltworks was his special care.

Understanding that the precious lifeline of the Confederacy, meaning its

much depended upon salt which was necessary for preserving food and curing leather, was in Jones' special care,

Stringfillow already knew that it was going to take Secretary of War Seddon himself to drag Jones away from Glade Spring.

As Jones was dictating his report from Glade Spring on May 7th

to Stringfellow, Averell, in almost prophetic fashion, had moved his command to nearby Tazewell County in a planned

offensive on Saltville. After the Union general heard and read reports of the force that was between he and the salt

facilities, an easy decision was made to turn his 2,000 cavalry veterans and move on the railroad instead.

Averell turned back because he had ascertained that there was a large force of some 5,000 men commanded

by Jones and John Hunt Morgan near Saltville. By 1864 standards Jones had a behemoth of a brigade, and the sheer

size of his 4,000-man army (which Averell thought to be 5,000) would force Brig. Gen. Averell to rethink advancing

his cavalry division of 2,000 toward its objective of laying waste to the salt facilities, and instead turn toward and

continue his destruction of the Virginia and Tennessee railroad.

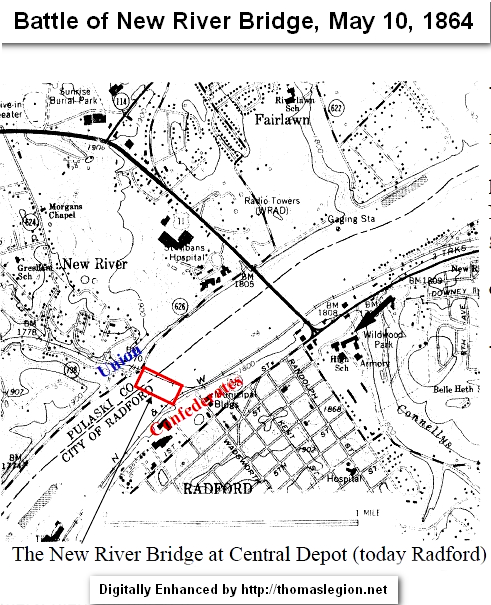

| Battle of New River Bridge, May 10, 1864 |

|

| Union and Confederate armies at New River Bridge |

| Cloyd's Mountain Battlefield on May 9, 1865 |

|

| Union and Confederate battle lines at Cloyd's Mountain |

| Official Records for the Civil War |

|

| Jenkins makes pleas for more troops |

Brig. Gen. Averell would soon push his division in the direction of

Wytheville with the objective of destroying the railroad and reinforcing Crook. En route, Averell's division would

enter Wythe County and engage the 4,000-man brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. Jones. Averell, well rested,

would open the Battle of Cove Mountain on the afternoon of May 10th, and then press the Confederates in Hood-Nashville form,

but after four hours of the one-sided contest it would be Averell acquiescing and limping off the field this time, and

then he would link up with Crook and move his exhausted command back into West Virginia.

Confederate colonels William L. Jackson and William H. French, respectively,

had a brigade of 1,425 men, of which 80 were mounted, on May 9th. Most of Col. Jackson's horses were unfit for service

and abandoned in Monroe County, West Virginia, so his cavalry brigade, being dismounted, proceeded on foot.

While Jackson was advancing from Union, about 70 miles from Dublin, French was at Narrows holding the road,

but the battle would commence and conclude without their dismounted force on the scene.

While Brig Gen. Jones knew the positions of his fellow brigades, they

didn't necessarily know his location nor who was commanding the department on May 9th. Some surmised that it was Jenkins

at Dublin, while others believed it to be Jones or McCausland, but the common thought on the 9th was one of confusion. While

Jenkins had sent requests to regiments, companies, and batteries to make haste for Dublin, Jones had in concert been issuing his own orders to some of the same units. There were many members of the

body on that day, but it was the head that seemed to be missing. Breckinridge too was culpable, because the major-general

had many opportunities to issue orders through proper channels informing the department stating who exactly was their

commander during his absence. His dispatches stating who was the interim commander were loosely stated to Jenkins

and Jones, but it lacked the military orders that were generally associated with the department commander's absence.

Whereas Jenkins had continually informed the department and command of

his movements and objectives, Jones had utterly refused to communicate with anyone other than Breckinridge and the

assistant adjutant general it seemed. His actions or inactions had served only to widen the gap and lengthen the

distance between every unit within the department. The stated distance of Jones could only be covered quickly

by train, but Crook and Averell had been tearing the rails for days as they traversed that region. He had other

motives for moving his command near Abington. Jones, though absent from the state, presently commanded the

Department of East Tennessee, so by moving his brigade to Glade Spring, now 70 miles from Cloyd's Mountain, he was

now merely 30 miles from the Tennessee border. But he had at least one other motive for locating his command there. Prior

to the Civil War, Jones had served in the U.S. Army until resigning his commission in 1857, the same year he bought his

farm which just happened to be in Glade Spring. If afforded, familiarity of terrain is always a good advantage during

battle, particularly if happens to be the ground that hosts your own farm as well as the railroad that can

move a force toward Wytheville and Dublin or even nearby Tennessee.

Jones was commanding his East Tennessee department with much of it now

in southwestern Virginia, but although informed by Breckinridge to work as co-captains of the front with Jenkins,

he operated solely as an independent command within the geography of another command, which served only to be problematic.

During the Cloyd's Mountain battle, Jones had indeed been communicating (not with Jenkins of course) with his own East Tennessee

department. He had ordered Brig. Gen. Alfred E. "Mudwall" Jackson to operate close to the Virginia line in case he, Jones,

needed him, and he sent telegrams ordering his regimental commanders where to position their units and to be prepared

to move into southeastern Virginia as directed. After the battle of Cloyd's, it was Stringfellow himself who complained

to Breckinridge on May 11th and 13th, saying that Jones has not replied to his telegrams. "Grumble" Jones did surface

on the 16th in a telegram he wired to Gen. Cooper requesting that Vaughn's brigade remain and assist

in the retaking of East Tennessee, for he believed it could be done. But unfortunately on the 17th, and eight days after

the battle, when two orders were issued to the same regiment, Col. French would ask Col. Jenkins, who is in command,

you are Jones?

| Map of Civil War Railroads |

|

| Map of strategic location of Cloyd's Mountain adjacent the only railroad |

Jones was enjoying much success as a department commander, according to the thoughts of at least one superior,

because less than one week ago, May 2, 1864, General Bragg had personally nominated him for promotion to the rank

of major-general. Still, Jones believed that Glade Spring would allow him to move his brigade more readily on the location's

railroad, that is if the 70 mile long track leading to Jenkins had not been ripped.

Jones, however, would not attain the promotion. During the battle of Piedmont on June 5th, less than one month away, Jones would

be leading a charge only to be shot and killed during the process. Although the Confederates would lose at Piedmont,

it was the more than 25% total casualties that made it an even more devastating defeat for the South. Brig. Gen.

William E. Jones, the fighter, farmer, turned fighter again, was known as "Grumble" because he was a hot tempered man,

but he was a general who inspired his men and who brought the "fighters" to the battle. Jones was a leader, a general whose

courage and tenacity would make men willing to charge hell itself if asked to do so.

| Cloyd Mountain Battlefield, Official Records |

|

| The storm is beginning to batter the front |

As Jones was nestled at Glade Spring with his 4,000 troopers, Brig.

Gen. George Crook broke camp on the morning of May 9th, and moved his men south to the top of a spur of Cloyd's Mountain.

Before the Union troops lay a precipitous, densely wooded slope with a meadow about 400 yards wide at the bottom. On the other

side of the meadow, the land rose in another spur of the mountain, and there Jenkins' men

waited behind hastily erected fortifications. Crook dispatched the third brigade under Colonel Carr B. White to work its way

through the woods and deliver a flank attack on the Rebel right. At 11 am, he sent Hayes' first brigade and Colonel Horatio

G. Sickel's second brigade down the slope to the edge of the meadow, where they were to launch a frontal assault on the Confederates

as soon as they heard the sound of White's guns. The slope before them was so steep that the officers had to dismount and

descend on foot.

Crook stationed himself with Hayes' brigade, which was to lead the assault.

After a long, anxious wait, Hayes at last heard cannon fire off to his left and led his men at a slow double time out onto

the meadow and into the Confederate musketry and artillery fire, which Crook called "galling". Their pace quickened as they

neared the other side, but just before the base of the slope they came to a waist-deep creek. The barrier caused little delay

and the Yankee infantry stormed up the hill and engaged the Rebel defenders at close range. The only man to have trouble with

the creek was Brig. Gen. Crook. Dismounted, he still wore his high riding boots, and as he stepped into the stream, the boots

filled with water and bogged him down. Nearby soldiers grabbed their commander's arms and hauled him to the other side.

Vicious hand-to-hand fighting erupted as the Yankees reached the crude Southern

defenses. The Southerners gave way, tried to re-form, then broke and retreated up and over the hill towards Dublin. The Northerners

rounded up 200 Rebel prisoners and seized Jenkins, who had fallen wounded. At this point the discipline of the Union

men wavered, and there was no organized pursuit of the fleeing enemy. Crook was unable to provide leadership as the excitement

and exertion had sent him into a faint.

Colonel Hayes, who had remained calm, organized a force of about 500

men from the soldiers milling about the site of their victory. With his improvised cavalry

command, he set off, closely pressing the Rebs. While the fight at Cloyd's Mountain

was nearing conclusion, a train pulled into nearby Dublin station with scarcely more than 400 fresh troops of Brig. Gen. John

Hunt Morgan's dismounted cavalry.

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain Map |

|

| Civil War Cloyd's Mountain Battle |

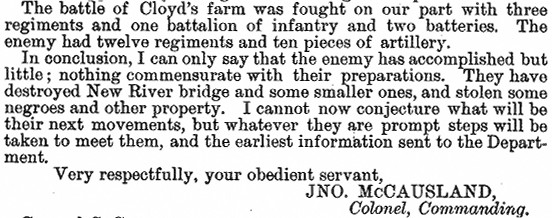

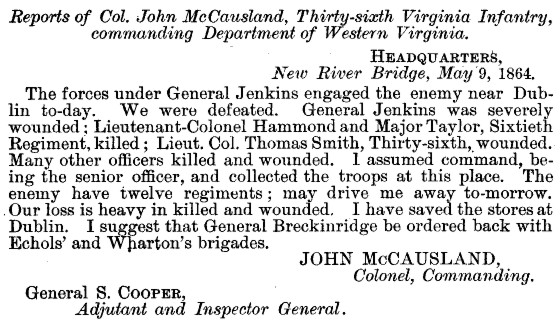

| McCausland's after battle report |

|

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain results |

Colonel D. Howard Smith, commanding Morgan's (dismounted) cavalry,

was moving from Saltville with his entire command, numbering some 750 men, to Dublin to reinforce the Confederates.

Smith reported that he proceeded by rail in the direction of the

point of his destination, but since the locomotive was derailed, he did not reach Dublin until 1 p.m. the next day and

with scarcely 400 men, the other 350 having been left at Glade Spring, near Abingdon, which was some 70 miles from the

battle. When he arrived on the field, the fight had been raging for several hours at Cloyd's Mountain. The

scene made it obvious that McCausland's men had been thoroughly routed with many demoralized and straggling soldiers leaving

the field.

Col. D. Howard Smith advanced

his dismounted brigade at quick time toward the battlefield only to see a routed and disorganized Confederate retreat in progress.

Col. McCausland, who had assumed command upon Jenkins being wounded and

captured, was gallantly and spiritedly trying to rally his shattered command, but to no avail. Smith reported to

McCausland for orders and then barked commands to his fresh troops who immediately formed in the woods to the left of the

road. The reinforcements halted the rout, but

Colonel Hayes, although ignorant of the strength of the force now before him, immediately ordered his men to "yell like devils"

and rush the enemy. Within a few minutes Brig. Gen. Crook arrived with the rest of the division,

and the defenders withdrew.

| McCausland assumes command during Cloyd's battle |

|

| McCausland's request for troops denied |

The seven hour battle of Cloyd's Mountain had cost the Union army 688 casualties,

while the Confederate's suffered 538 killed, wounded, and captured. Many officers were killed and wounded during the

engagement, and Colonel D. Howard Smith, commanding Morgan's dismounted brigade, stated that his command had suffered

the loss of 5 men, including 1 officer. The officer he lamented was Capt. C.S. Cleburne, the brother of Maj. Gen. Patrick

Cleburne, who fell while leading his men in a charge against the enemy. The young captain was said to be one the promising

young officers of the Confederate service. His elder brother Patrick would be killed six months later at the Second Battle

of Franklin.

Aftermath: Unopposed, Crook moved his command into

Dublin where he laid waste to the railroad and the military stores. A portion of his now exhausted but jubilant command, paraded

and passed through Dublin while shouting hurrah! hurrah! Crook then sent a party eastward to tear up the tracks and burn

the ties. The next morning, May 10th, the main body set out for their next objective, the New River bridge, a key point

on the railroad, a few miles to the east.

The Confederates, now commanded by Colonel McCausland, had arrived at the

New River bridge and crossed to the east side on the evening of May 9th. He then positioned Bryan's, Douthat's, and Dickenson's

batteries for the fight to come. On the morning of the 10th, at daylight,

Morgan's sharpshooters held positions near the river's edge. In his report to General Sam Cooper, Adjutant and Inspector

General, Richmond, McCausland described the west bank as pinning his smaller force to the river while leaving it without an

exit, so for strategic purposes he was forced to fight opposite Crook with artillery.

North and South would now fight from positions east and west of

the prominent New River bridge.

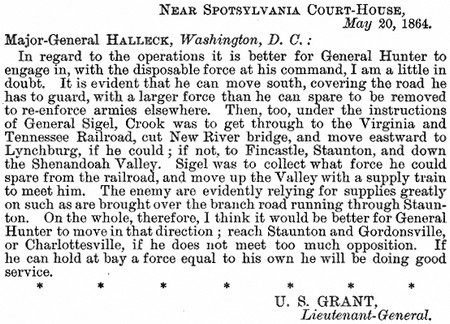

| General Grant weighs in with his strategy |

|

| Grant discusses Crook's objectives in southwestern Virginia |

| Civil War New River Map |

|

| Battle of New River Map |

While the Confederates waited on the east side of the New River to

defend the 700-foot long bridge, Crook arrived on the west bank, and pushing back some sharpshooters of Morgan's brigade, an

artillery duel ensued for about three hours. McCausland wrote that his artillery, along with many men, had been forced

back during the superior artillery of the enemy. At about the third hour, the Confederate artillery had exhausted its

ammunition, while many of the much needed horses, the muscle necessary to move the guns, had been killed

during the cannonading. A scout reported to McCausland and described a large body of Union infantry, which would

soon be revealed as the main body of Crook's army, crossing the New River, seven miles below at Pepper's Ferry, and was

marching on his position. While the acting commander began what he described as an orderly withdraw, he sent dispatches

with orders to all available units to come to his immediate aid.

With silent guns from across the river, Crook ordered the bridge destroyed,

and both sides watched in awe as the structure collapsed magnificently into the river. The New River Bridge at Central Depot

(today Radford) had a 700-foot long wooden superstructure and was supported by massive stone piers anchored in the river bottom.

Crook reported 1 killed and 10 wounded during the duel. McCausland, without the resources to oppose the Yankees any further,

withdrew his battered command to the east. While Crook would be commended for thrashing the Confederates, he would be

the praise of the Union army, even receiving acknowledgement from Lt. Gen. Grant for downing the vital bridge.

McCausland now marched his cautious but determined command to

meet the Union infantry which had crossed Pepper's Ferry. While the battle weary men were advancing through Christiansburg, 20

miles east of Dublin, fellow units, with the exception of "Grumble" Jones, had moved according to his dispatches. He

then pushed east to Big Hill, seven miles west of Salem, where he posted his force to

meet the enemy which had passed though Pepper's Ferry and moved to Blacksburg. McCausland had reached Big Hill on the

11th, and remained there on the 12th.

Brig. Gen. Crook, who had shattered

the smaller Confederate force at Cloyd's on May 9th, and destroyed the grand bridge at New River on the 10th, was

retiring toward Blacksburg, which is 20 miles northeast of Dublin. The 1,400 strong Rebel command of colonels

Jackson and French, responding eagerly to McCausland's orders, had moved from Narrows and was advancing on Crook's division

which was now north of Blacksburg. On the 12th, the troops of Jackson and French moved south and upon the rear of

the large Union command which was moving toward Salt Pond Mountain, but Crook pushed some 5,000 men into and repulsing

the Confederate contingent forcing it to fall back to Giles County (20 miles northwest of Blacksburg). Crook retreated

north marching toward Monroe, W.V., while Jackson and French moved to Gap Mountain,

about 7 miles northwest of Blacksburg, where they fought and scattered a portion of Averell's cavalry division.

On the 13th, McCausland's brigade was

in Christiansburg for supplies and rest, and French 's force was en route to occupy Narrows, while Jackson

moved his force toward Monroe to observe and report the movements of Crook.

Brig. Gen. Crook, supplies running low in a country not suited for major foraging, now rethought his orders

to push east and join Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley. At Dublin he saw dispatches from Richmond stating that General

Robert E. Lee had beaten and repulsed General U.S. Grant during the Wilderness

Campaign, which led him to consider whether the Confederate commander would soon move against Crook with a vastly

superior force, while allowing additional forces to march and press him from both the south and west catching him

in a trap. Having accomplished the major part of his mission, destruction of the Virginia and Tennessee railroad and the New

River bridge, Crook turned his two brigades north and after another hard march, reached and joined Averell's brigade

at Union on May 15th, and the division arrived at Meadow Bluff, West Virginia, on May 19th, thus concluding

the expedition.

The host force had little to be excited about, although McCausland, who

would live until 1927, tried to downplay the Union expedition by saying that it accomplished but little. That, however,

was far from the truth, because the Dept. of Western Virginia had lost a sizeable fraction of its command, including its commanding

officer, and the region had much rail ripped from the line causing the ebb and flow of transportation to grind to a dead

halt. The skeleton department would later surrender Breckinridge to the exigencies of the conflict, for he would serve

as Secretary of War from February 6, 1865 to May 10, 1865. Emboldened by its success, the Union army would increase

its assaults on the region, which would lead to the eventual capture and destruction of the much needed salt

facilities at Saltville in December 1864. Although the Federals had burned the New River bridge, its superstructure

survived, leaving the colossal stone piers intact because the necessary explosives had been left in West Virginia. The

Confederates would rebuild the bridge span within five weeks, but while they could rebuild bridges they could not

so readily replenish their depleted ranks, however.

Analysis: The

lack of command and control of the Department of Western Virginia during the absence of Maj. Gen. John Breckinridge played

a critical role in the defeat of the Confederate army at Cloyd's Mountain. Although Breckinridge would be absent, he had failed

to adhere to protocol formally relieving himself and transferring his command to Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins. As

Brig. Gen. George Crook executed a nearly flawless assault at Cloyd's Mountain, he was able to follow Grant's plan, even

while his army exited the region, by destroying the New River bridge and much of the Virginia and Tennessee railroad

there. Because Brig. Gen. William Averell engaged the largest enemy force in southwestern Virginia, his commander, Crook,

was free to flex Union muscle against a demoralized foe at the New River bridge. Crook had pressed the advantage at Cloyd's causing

his nemesis Jenkins to be mortally wounded and captured. The Union cavalry veteran had known of Breckinridge's departure

and now he had captured his second in command, which was mortally wounded. Averell had accurately assessed the size and

movements of Brig. Gen. William Jones' cavalry, but instead of feints or a demonstration he pushed, in an unnecessary and

costly contest, his 2,000 strong cavalry into a four hour struggle with the Rebel cavalry force of 4,500. While unity of command

had been enjoyed among the Yankee command, the Confederates had unwilling and uncooperative commanders during the action,

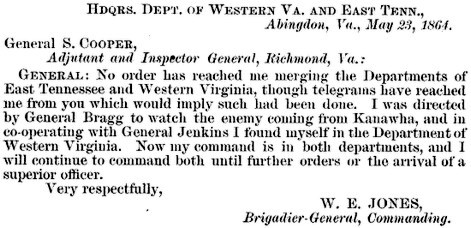

resulting in a divided army which would easily be defeated.

Unaccountability on the battlefield was as harsh as desertion on May

9th.

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain |

|

| Jones confirmed that he was to cooperate with Jones. |

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain History |

|

| Brig. Gen. Jones, commanding Dept. of East Tennessee |

(Right) While Jones had moved his soldiers into the neighboring department,

he did not cooperate or communicate with Jenkins at all. Since Jones' force had remained near Saltville, he

now acknowledged that it was not even the responsibility of his department. Although he admitted that he

been instructed to watch for the enemy, Jones had led his 4,500 cavalrymen as an independent force while in the

adjacent state. If Jones had cooperated with Jenkins and reinforced his position as requested, then this battle most likely

would have been written with a different outcome, but the same would also apply to the

narrative of Saltville. To divide and conquer the grand command of Jones and Jenkins was the enemy's objective as it forced

the battle, and the West Point grad Jones had fallen for it. That was the lesson, and now as a result the dwindling departments

would be forced to merge again.

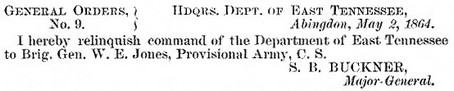

Brig. Gen. William Jones had assumed generalship of

the Department of East Tennessee effective May 2, 1864, and only three days before Maj. Gen. Breckinridge would

leave for Stanton under Gen. Lee's orders. Jones and Brig. Gen. Jenkins were to defend the front jointly,

stated Breckinridge to the brigadiers, but he never forwarded a circular within the command stating who was commanding

Western Virginia during his absence, which was the least that should have been done. His communication to Jones was also vague

and absent any direct language as to who was to command during his absence, but perhaps that had more to do with

Breckinridge believing that Jones was responsible for Saltville and was therefore already in the area, and that

he was also the newly appointed commander of East Tennessee. As he was moving a large fraction of the department

to assist Lee on the 5th, Breckinridge informed Brig. Gen. McCausland that Jenkins was now in commanding.

Jones and Jenkins had assumed the responsibility of their respective commands

within days of the battle of Cloyd's Mountain. From local departments to headquarters Confederate States, Richmond, there

had long been discussions and disagreements as to which department was responsible for Saltville. From December 1862 to May

1864, the debate had yet to be settled. Jones, having defended the salt facilities to date, believed that the geography belonged

to what was now his department, and in fairness to Jones, neighboring commands nor Richmond seemed to oppose him. Although Jones

was in southwestern Virginia and believed that it was his territory to defend, there were telegrams implicating

Jones as knowing that he was to assist Jenkins if necessary. Jones had sent his first telegram to his new department,

informing it that he was to assist and move his cavalry brigade according to Breckinridge's instructions, which meant to assist

Jenkins. A few weeks after the battle he stated that he had been cooperating with Jenkins (until his capture) in the

defense of the department, according to Breckinridge's instructions. But Jones in fact never responded to Jenkins' requests

nor made any effort to communicate with him.

Gen. Robert E. Lee, though it was a necessary move, remains partially to

blame for the outcome because of his swift transfer of a large portion of the department to the Army of Northern Virginia

just four days prior to the expected, imminent engagement. General Lee had initially received reliable intelligence in

March of 1864 about Grant's soon planned invasion of southwestern Virginia's salt facilities, lead mines, and railroads, from

a Confederate general whose near kin had heard about the plan merely be sitting at the dinner table with some of Grant's

generals who had assisted in strategy talks for the pending attack.

As a result of Cloyd's Mountain, the destruction of much railroad, and the

relative ease to which the Union army collapsed the New River Bridge, Gen. Robert E. Lee wrote to Secretary of War

James Seddon on May 25th, asking who has been commanding the department since the death of Jenkins. Was it John Hunt Morgan? Was

it William E. Jones? The case is urgent, Lee continued. Mr. Secretary responded by saying that Gen. W. E. Jones had been

in command since the absence of Breckinridge, but Seddon was incorrect.

Breckinridge had been ordered by Lee to collect a force, which amounted

to three brigades totaling 4,000 men, roughly forty-percent of his entire department, and proceed to Stanton immediately.

Lee had difficult decisions to make on which front to protect, and although his dwindling forces were already stretched, the

Confederate capital of Richmond had to be protected at all

hazards. Although Breckinridge was ordered to remove McCausland's 1,500 strong brigade from his army prior to moving to

Stanton, he would subsequently regain the brigade and march it into the fighting in the Shenandoah Valley.

Jones, meanwhile, although in the

department, was commanding another region known as the Department of East Tennessee. Seddon also referred to the host

department erroneously as the Department of southwestern Virginia, confirming that command and control of the Department of

Western Virginia was at a crisis, but unfortunately it would never recover. Breckinridge, under orders from Lee,

had taken forty-percent of the department on May 5th to Stanton where it would proceed and fight in the Shenandoah Valley

Campaigns of 1864-65. The remaining force would eventually merge with the Department of East Tennessee, and then it would

be reduced to a token, skeleton force as Lee required every available man to assist in the defense of the capital during the

Richmond-Petersburg Siege.

The leaderless Confederate command

would never recover from the loss, but it would remain determined in its defense of the saltworks at all hazards. Breckinridge

would later return to lead a small garrison, only to be pushed off the field to observe the superior Union

numbers destroy the salt capital of the nation. Perhaps a microcosm of the conflict itself in 1864, southwestern Virginia

would mirror much of what the Confederacy would experience during the waning 12 months of Civil War. A war

of attrition was simple arithmetic between the North and South in '64, and it couldn't be avoided or ignored. Knowing

that lost troops would not be replaced, it was an inescapable slap of reality for the command at Richmond.

| Virginia Civil War Leaders and Commanders |

|

| Leadership of the now unified command remained problematic |

Lee had good cause to be concerned about his flank, too, because it would

later prove to be another highway for the Union army. Lee would soon be pinned down in the Richmond-Petersburg trenches and

require all available units to assist in the defense of the Confederate capital, leaving the department void. And while Union

Maj. Gen. George Stoneman (highest ranking Federal prisoner-of-war) would go unopposed in the area as he burned and destroyed

its infrastructure, Union cavalry commander, Phil Sheridan, would destroy the remnants of Lt. Gen. Jubal Early's force

in the Shenandoah Valley, and then return to assist Lee. Maj. Gen. William Sherman, in concert, would turn his army north

from Savannah and slice through the Carolinas as he moved closer to linking up with Sheridan and Grant against Lee.

Casualties: The total Casualties for both Union and

Confederate armies were drawn from the final casualty tabulations, including company, regimental, brigade, and division

reports, with respective adjustments, and include Cloyd's Mountain, Jeffersonville, and New River bridge. The initial

tabulations from both Union Brig. Gen. Crook and Confederate Col. McCausland were included and subsequently amended. After

reviewing numerous casualty reports and returns from the regiments and units engaged at Cloyd's Mountain, they were

found to contain the usual estimates, embellishments and exaggerations that are in the Official Records of

the Union and Confederate Armies.

For example, Crook said in an earlier tabulation that during the

battle his men had captured 230 prisoners, in addition to the wounded, and afterwards buried more than 200 of the enemy

dead on Cloyd's Mountain, but his company and regimental commanders offered no such numbers nor activity in their respective

reports. Crook also reported that there must have been between 800 and 1,000 Confederates in killed and wounded, but that

remark, however, although opined was incorrect. Crook continued by saying that several sources informed him that hundreds of Jenkins'

men had deserted and that several Confederates had joined him, but that too was false.

McCausland, however, initially attempted to qualify and perhaps lessen the

sting of the drubbing at Cloyd's Mountain by saying the enemy had an aggregated force of 9,000 men of all arms,

while his force remained shy of 3,000. While he was referring to the combined force of Crook and Averell, he had only engaged

Crook on May 10th. While he also recorded Crook's losses at 600 but believed the total casualties to rise to at least

1,000, McCausland's assumption about the size of the force that had defeated him on that day was obviously incorrect, even

if one included Averell's division, but his statement of Union losses of 600 should be considered an outstanding after

battle report. While Crook gave an exact accounting of the total Confederates that his command had buried and captured,

McCausland affirmed enemy troop strength and total casualties. Having viewed the disparities between all available tabulations

for said battle, the final adjusted reports of opposing commands were found to be the most accurate. After the casualty

reports were corrected and made final, neither side refuted the Confederate or Union casualty totals, but actually affirmed

the reports in diaries and memoirs. But unfortunately, many authors and even historians still apply the

preliminary and exaggerated numbers for the action.

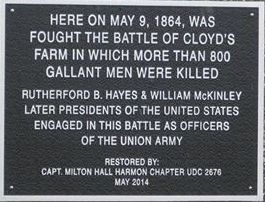

(Right) The battle on May 9, 1864, extended from Cloyd's Mountain to the Cloyd

farm, and the fight has historically been known by both names. The total Union

and Confederate men in killed was actually less than 200. The historical marker is incorrect with its total killed of

800, and it would have been nice if the restoration money would have been applied toward a new marker with correct

information. The erroneous total of more than 800 is most likely drawn from some of the initial after battle reports which

contained false and exaggerated casualty numbers.

Preliminary reports, or after

battle accounts, were well-known for their inaccuracies. After a skirmish or battle, regardless of the outcome, each unit,

whether artillery, cavalry, or infantry, would as soon as possible have roll or muster call to verify men present.

Each company commander, having performed a head count, would ascertain his losses and then forward the casualty tabulation

to his regimental commander, who would review each company's numbers and then tabulate a regimental casualty

report and forward it to his commander, whether brigade or headquarters. The brigade would review the subordinate casualty

figures and also make its casualty report. A week later, the initial or preliminary report may be incorrect, because missing-in-action,

for example, may be changed from missing to killed or even prisoner. A wounded soldier listed in the first report, such

as Brig. Gen. Albert Jenkins, was initially indicated as wounded and captured, only to be listed as mortally wounded 10

days later. With all wars, morale is vital to the unit and to the nation, so casualty figures were known to be intentionally

misstated. There are numerous casualty reports in the official records, having never been corrected, that are so

grossly embellished, it's beyond farcical. Because of said scenarios, accurate casualty reports are not always easy

to obtain. There are other reasons, too, such as the end of war causing many Confederate units to destroy their

records lest they be captured and used as evidence in support of treason or war crimes. See also Union and Confederate Casualty Reports for Battle of Cloyd's Mountain.

Major Thomas L. Broun's recollection

of the battle of Cloyd's Mountain, Richmond, VA. 1909.

Broun served as volunteer aide on Colonel Beuhring Jones' staff, of the

Sixtieth Virginia Regiment, and was assigned to duty in the most contested area on that bloody day. Although written some

45 years after the battle, the numbers and events are recalled clearly and support other accounts of this fight.

Broun restated the casualties as follows: "The Federal loss in this

battle was 108 killed, 508 wounded and 72 captured or missing (688 Total); the Confederate loss 76 killed, 262 wounded and

200 captured or missing (538 Total). The casualties were mainly in the Thirty-sixth Virginia Infantry Regiment, Morgan's dismounted

men, and the Forty-fifth Virginia Battalion. Crook's force was three times as great as that of the Confederate, under Jenkins

and McCausland."

(Sources and related reading below.)

Recommended

Reading: Lee's Endangered Left: The Civil War In Western Virginia, Spring Of 1864. From Kirkus Reviews: A competent, well-executed addition to the

ever-growing horde of Civil War literature, by Duncan (History/Georgetown University). The author reconsiders Union General

Ulysses S. Grants attempts to destroy the Confederates, led by General Robert E. Lee, at their traditional stronghold in western

Virginia and his efforts to threaten Lynchburg

during the spring and summer of 1864. Continued below…

The writing

here is crisp; refreshingly, our chronicler pays sharp attention to the effects of the campaign on civilians as the Union

army penetrated beyond its supply lines and came to live off the countryside in one of the Confederacy’s richest agricultural

regions, bringing home the harsh realities of war to civilians. The campaign swung back and forth, with Northern victories

at Cloyd's Mountain and New

River Bridge and Confederate routs at New Market, followed by a Union

failure to seize Lynchburg. Though the campaign proved costly

to the South, overall the Unions hope to capture the Shenandoah Valley foundered and the Confederates then went on to threaten

Washington, D.C. Duncan sensitively employs a wide variety of sources, military and civilian, to add to the coherence of his

account. Still, the books scope remains narrow, focusing on a not terribly glamorous period in the wars history; then, too,

wed do well to have the volume trimmed by a third. Duncan’s contention that the Unions

severity in dealing with civilian populations was directly reciprocated when the Confederates took Chambersburg,

Penn., creating a chain of vengeance that culminated when Sherman marched through the South, is insightfully argued, offering a fresh analysis to the

historical debate. Casual readers of the Civil War genre (and many die-hard buffs, as well) may want to leave this superbly

researched yet ultimately too specialized study for the historians to ponder. Includes 20 photographs.

Recommended Reading: Saltville (VA) (Images of America), by Jeffrey C. Weaver (Author), The Museum of the

Middle Appalachians (Author): Description: Saltville, Virginia, lies on the banks of the North Fork of the Holston River on

the border between Smyth and Washington Counties. Its history began very long ago; in fact, archeological evidence suggests

extensive human habitation there for more than 14,000 years. Saltville was named because it was a source of salt,-and by the

end of the 18th century, a thriving industry was born. During the Civil War, Saltville attained considerable importance to

the Confederate government as a supply of salt. Continued below…

A large Confederate

army garrison was maintained there, and extensive fortifications were constructed. After the Civil War, the town led the way

in industrialization of the South. Flip through the pages of Images of America: Saltville to learn why Saltville is one of

the most historic places in the world. About the Author: The Museum of the Middle Appalachians, located on Palmer Avenue

in Saltville, was established by the Saltville Foundation in the 1990s. It has become the repository for fossils, artifacts,

and photographs of the region. Author Jeffrey C. Weaver holds degrees in American history from Appalachian State University,

and after serving in the U.S. Army for several years, he worked as a contracting officer for the U.S. Department of Energy.

He is currently the manager of the Chilhowie Public Library.

Recommended

Reading: Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign, by Peter Cozzens (Civil War America)

(Hardcover). Description: In the spring of 1862, Federal troops under the command of General George B. McClellan launched

what was to be a coordinated, two-pronged attack on Richmond

in the hope of taking the Confederate capital and bringing a quick end to the Civil War. The Confederate high command tasked

Stonewall Jackson with diverting critical Union resources from this drive, a mission Jackson fulfilled by repeatedly defeating

much larger enemy forces. His victories elevated him to near iconic status in both the North and the South and signaled a

long war ahead. One of the most intriguing and storied episodes of the Civil War, the Valley Campaign has heretofore only

been related from the Confederate point of view. Continued below…

With Shenandoah

1862, Peter Cozzens dramatically and conclusively corrects this shortcoming, giving equal attention to both Union and Confederate perspectives.

Based on a multitude of primary sources, Cozzens's groundbreaking work offers new interpretations of the campaign and the

reasons for Jackson's success. Cozzens also demonstrates instances

in which the mythology that has come to shroud the campaign has masked errors on Jackson's

part. In addition, Shenandoah 1862 provides the first detailed appraisal of Union leadership in the Valley Campaign, with

some surprising conclusions. Moving seamlessly between tactical details and analysis of strategic significance, Cozzens presents

the first balanced, comprehensive account of a campaign that has long been romanticized but never fully understood. Includes

13 illustrations and 13 maps. About the Author: Peter Cozzens is an independent scholar and Foreign Service officer with the

U.S. Department of State. He is author or editor of nine highly acclaimed Civil War books, including The Darkest Days of the

War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth (from the University

of North Carolina Press).

Recommended

Reading: Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Spring 1862. Description: The Valley Campaign conducted by Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson has long fascinated

those interested in the American Civil War as well as general students of military history, all of whom still question exactly

what Jackson did in the Shenandoah in 1862 and how he did

it. Since Robert G. Tanner answered many questions in the first edition of Stonewall in the Valley in 1976, he has continued

to research the campaign. This edition offers new insights on the most significant moments of Stonewall's Shenandoah triumph.

Continued below…

About the Author:

Robert G. Tanner is a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute. Tanner is a native of Southern California, he now lives

and practices law in Atlanta, Georgia. He has studied and lectured

on the Shenandoah Valley Campaign for more than twenty-five years.

Recommended

Reading: Three Days in the Shenandoah: Stonewall Jackson at Front Royal and

Winchester (Campaigns and Commanders)

(Hardcover). Description: The battles of Front Royal and Winchester

are the stuff of Civil War legend. Stonewall Jackson swept away an isolated Union division under the command of Nathaniel

Banks and made his presence in the northern Shenandoah Valley so frightful a prospect that

it triggered an overreaction from President Lincoln, yielding huge benefits for the Confederacy. Continued below…

Gary Ecelbarger

has undertaken a comprehensive reassessment of those battles to show their influence on both war strategy and the continuation

of the conflict. Three Days in the Shenandoah answers questions that have perplexed historians for generations. About the

Author: Gary Ecelbarger, an independent scholar, is the author of Black Jack Logan: An Extraordinary Life in Peace and War

and "We Are in for It!": The First Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862.

Recommended

Reading: Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Description: Jubal A. Early’s disastrous battles in the Shenandoah Valley

ultimately resulted in his ignominious dismissal. But Early’s lesser-known summer campaign of 1864, between his raid

on Washington and Phil Sheridan’s renowned fall campaign, had a significant impact on the political and military landscape

of the time. By focusing on military tactics and battle history in uncovering the facts and events of these little-understood

battles, Scott C. Patchan offers a new perspective on Early’s contributions to the Confederate war effort—and

to Union battle plans and politicking. Patchan details the previously unexplored battles at Rutherford’s Farm and Kernstown

(a pinnacle of Confederate operations in the Shenandoah Valley) and examines the campaign’s

influence on President Lincoln’s reelection efforts. Continued below…

He also provides

insights into the personalities, careers, and roles in Shenandoah of Confederate General John C. Breckinridge, Union general

George Crook, and Union colonel James A. Mulligan, with his “fighting Irish” brigade from Chicago.

Finally, Patchan reconsiders the ever-colorful and controversial Early himself, whose importance in the Confederate military

pantheon this book at last makes clear. About the Author: Scott C. Patchan, a Civil War battlefield guide and historian, is

the author of Forgotten Fury: The Battle of Piedmont, Virginia, and a consultant and contributing writer for Shenandoah, 1862.

Review

"The author's