|

Battle of Cove Mountain

Other Names: Battle of the Cove; Battle of Crockett's Cove; Battle

of Crockett's Farm; Battle of Grassy Lick

Location: Wythe County, Virginia

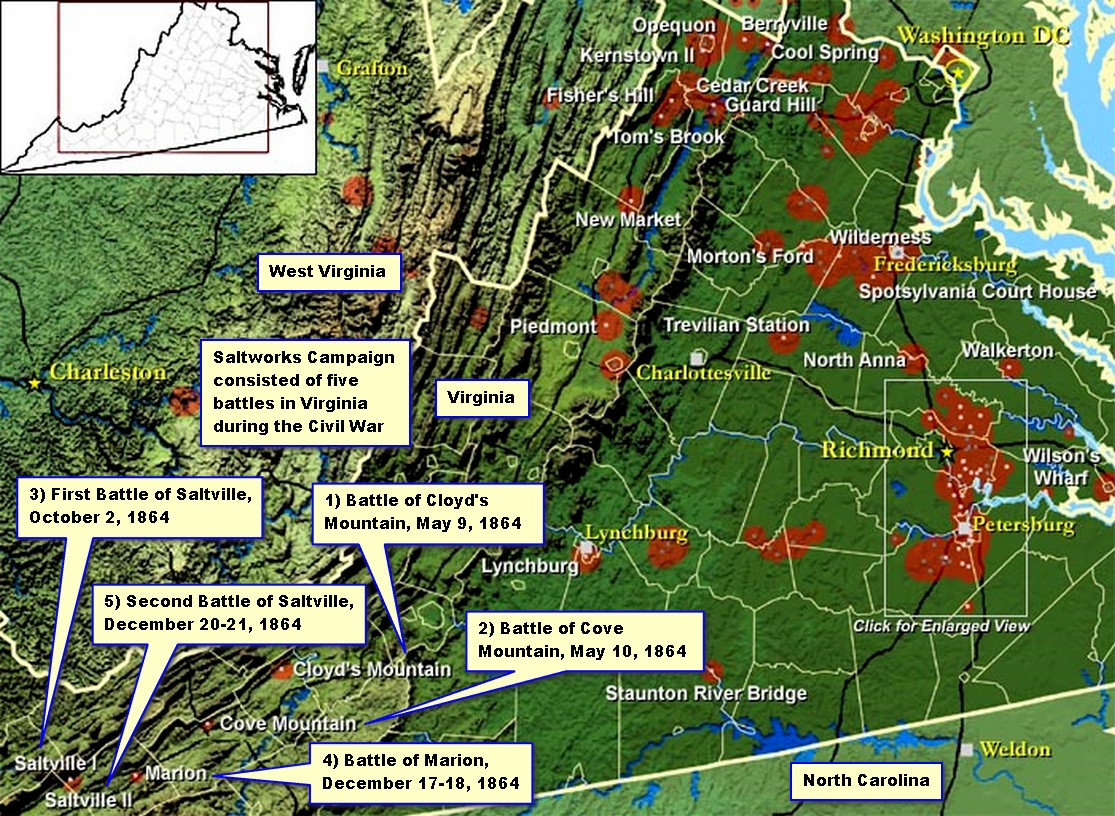

Campaigns: Crook-Averell Raid on the Virginia & Tennessee

Railroad (May 1864); Virginia Saltworks Campaign (May-December 1864)

Date(s): May 10, 1864

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. William W. Averell [US]; Brig.

Gen. William. E. Jones [CS]

Forces Engaged: Brigades

Estimated Casualties: 175 est. (US 150) (CS 25)

Result(s): Confederate victory

Summary: The Battle of Cove's Mountain was the second of five

engagements during the Virginia Saltworks Campaign. The campaign consisted of a series of attempts by the Union army to capture

and destroy the largest producer of salt for the Confederacy at Saltville, Virginia. On May 10th, east of Crockett's house,

Brig. Gen. William Averell’s cavalry force, consisting of two brigades, encountered the brigades of brigadiers William

“Grumble” Jones and John Hunt Morgan near Cove Mountain. The Union cavalry fought while dismounted for the engagement,

but they were checked during each advance by Confederate artillery and infantry. Averell believed he was improving his

position after each advance against Jones' brigade of mainly infantry. While remaining in line, Brig. Gen. John Hunt

Morgan's 500-man cavalry brigade, dismounted, led a single vicious countercharge, with Jones' men following, forcing

Averell from the scene. The Union cavalry withdrew and proceeded directly toward the New River Bridge on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad where it arrived on the following day, May 11th. While his superior,

Brig. Gen. George Crook, had already burned the bridge, May 10th, Averell was content knowing that his cavalry division had

occupied the enemy while also destroying several miles of the Virginia and Tennessee during his stay. He then withdrew

his battered force and marched toward West Virginia where he would unite with Crook, who had routed the Confederates

on May 9th at nearby Cloyd's Mountain.

| Battle of Cove Mountain Map |

|

| Battle of Cove Mountain and the Civil War Saltworks Campaign |

| Civil War Battle of Cove Mountain, Virginia |

|

| Battle of Cove Mountain Map |

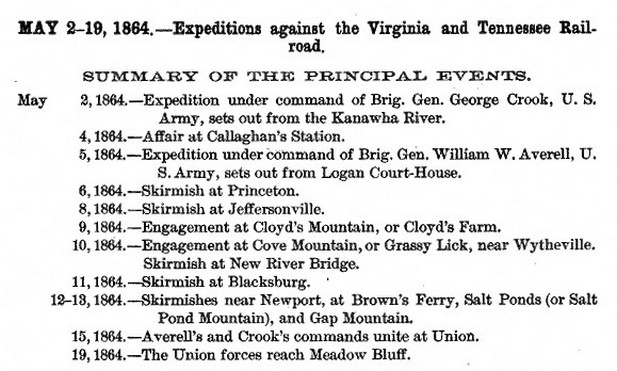

| Union Summary of Principal Events |

|

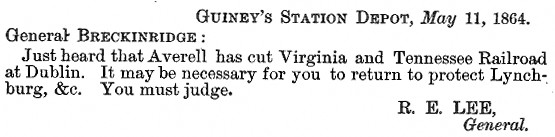

| Battle of Cove Mountain History. Official Records. |

History: On May 1, 1864, at Charleston, West Virginia,

Union Brig. Gen. William W. Averell (West Point class of '55), at the direction of Brig. Gen. George Crook, commanding the

expedition, began to move his division, consisting of the brigades of Brig. Gen. Duffie (fought in Crimean War) and Colonel

Schoonmaker (future Medal of Honor recipient), numbering in all 2,079 officers and men, and 400 of the 5th and 7th West Virginia

Cavalry. The orders he received from Crook were to move against and destroy the saltworks at Saltville, Virginia. On May 2nd,

Crook (famous Indian fighter after the Civil War) marched his Kanawha Division out of Kanawha Valley and headed

south with the objective of destroying the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad. He forwarded Averell on another route into southwestern

Virginia as to keep the enemy from knowing his exact plans and to reduce the size of the large contingent.

Confederate Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge (cousin to First Lady Mary Todd

Lincoln) had assumed command of the Department of Western Virginia on Feb. 25, 1864, relieving Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones (West

Point class of '41). Breckinridge, the former U.S. Vice President serving under James Buchanan, had been receiving

regular reports from his scouts on the movements of the Kanawha force and Averell's division, but it wasn't until May 2nd

that Breckinridge had conviction about the plan of the enemy.

While the Department of Western Virginia had already been wanting by

May of 1864, Breckinridge was now ordered by Lee to collect a force, which amounted to three brigades totaling 4,000 men,

40% of his entire department, and proceed to Stanton immediately. Breckinridge would eventually move the three brigades

into the fighting in the Shenandoah.

Upon being ordered to Stanton, Breckinridge hastily instructed Brig.

Gen. Albert Jenkins to assume temporary command on May 5th, directing he and Brig. Gen. William "Grumble" Jones (West

Point class of '48) to coordinate and cover the front. Lee had very tough decisions to make on which front to protect,

and although his dwindling forces were already stretched, the Confederate capital of Richmond remained priority one. Absent,

Breckinridge would continue sending several dispatches informing Jones of Averell's movements.

On May 9th, the day prior to the fight at Cove Mountain, Jenkins had

been wounded and captured during the nearby battle of Cloyd's Mountain, only to die less than two weeks later in a field hospital. Jenkins,

however, had pled his case to Breckinridge a few days prior to battle. He held scouting reports indicating the strength

of Brig. Gen. George Crook's Union command as it slugged through the region tearing up much of the Virginia and Tennessee

railroad. Jenkins had said to the major-general that unless he receives additional troops, he believed that his small

command of 2,400 would be shattered. Jenkins, a former U.S. Congressman, had accurately predicted his own death. While

his force had been routed on May 9th, it was Col. D. Howard Smith, commanding John Hunt Morgan's brigade, that staved

off an even bloodier scene for the Rebels.

Brig. Gen. Jones was now defending the region alone and absent any sizeable

reinforcements from the remnants of Jenkins' command, but he was also commanding two departments, the other being the Department

of East Tennessee. Both departments would eventually merge as Lee became entrenched against Grant before Richmond.

Brig. Gen. Averell had recently abandoned his objective of destroying

the saltworks at Saltville on May 8th, because he ascertained that brigadiers William E. Jones and John Hunt Morgan had

a combined force of at least 4,500 soldiers well defended in earthworks with artillery at the location.

Averell now turned and marched his two brigades in the direction of Wytheville

with the objective of destroying the railroad and reinforcing Crook. En route, Averell's division of 2,000 strong entered

Wythe County and engaged the 4,000-man Confederate brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. William Jones. Averell, well rested,

opened the Battle of Cove Mountain on the afternoon of May 10th. He would attack the Confederate center, and both flanks in

almost Hood-Nashville form, but it would be Averell acquiescing and limping off the field.

This fight pitted Federal cavalry against Confederate infantry and artillery.

The Confederate position, similar to the Spartan 300, was formed by wedging its infantry and artillery into what

was now a fortified pass. You either went through the pass or circumnavigated it, but Averell, who had earlier averted

this same force because of its numbers and position near Saltville, decided to push the offensive this time.

As Jones watched Averell's horsemen arrive to his front, he already

understood that the Union commander had the singular objective of destroying his massive infantry command on that

day of May 10, 1864. Jones too had one objective, to remain defensive in his Gibraltar. Averell had intentionally avoided

me once, believed Jones, but if he is here, he intends to fight this time. Jones had read Averell's hand. Companies of

Union cavalry began dismounting and forming in lines of battle directly in front of the gray clad bulwark. Jones

ordered his Confederates to hold their position as his artillerists adjusted their guns. The bulk of Averell's

dismounted troopers began pressing the enemy positions, only to be repulsed by grape and canister raking its ranks and

by disciplined rank and file infantry delivering crippling volleys.

The Union troops were quite disciplined as the Rebel command began to advance

the lines and push the Yankees back. Shells screamed over the advancing Confederates as they continued to press the Northerners. Averell re-formed

in what he believed would be the charge that broke the Confederate center. With momentum swaying at the third hour of

battle, wrote Averell, he, according to Confederate accounts, unleashed his cavalry and infantry for yet another assault.

Morgan's dismounted troopers led a countercharge this time and, with Jones' infantry following, pushed back the

Union lines, thus stealing the initiative and causing Averell to retire from the field. Morgan, according to official

records, chased the Union forces through the cove area of Wythe County, Virginia. Averell would later concede that if

it were not for Morgan, he may have held the field. The Confederates, having suffered but few losses according to Averell,

owned the battlefield as the sun went down. Though Union casualties were reported at 120 but later revised to 114 in

killed and wounded, Averell downplayed the fight as he reported Rebel strength of 5,000, but he already knew

the enemy's strength from his approach and withdraw before reaching Saltville.

| Reports for Cove Mountain Battle |

|

| Battle of Cove Mountain, Official Records |

| Southwestern Virginia Railroad and the Civil War |

|

| Averell cuts the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, Official Records |

In a report dated May 14th, 4:20 p.m., both a Union prisoner and a

Rebel scout stated to Confederate authorities that Brig. Gen. Averell had three brigades when he moved

on, and met Brig. Gen. Jones six miles from Wytheville, at Cove Mountain, on Tuesday, May 10th, and after a severe

fight fell back. A telegraph operator said to Confederate command that Averell had been wounded in the head during the

battle and was recovering at a hospital in Christiansburg, Virginia, on the night of May

12th.

On May 11th, Averell moved his exhausted brigade toward West Virginia

after failing to accomplish his main objective of destroying the saltworks, but his force was able to destroy some of

the much depended on railroads there, as well as occupy an enemy that would have otherwise

pressed Crook's division.

Gen. Crook, supplies running low in a country not suited for major foraging, now entertained second thoughts

about his orders to push east and join Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley. At Dublin he saw dispatches from Richmond stating that

General Robert E. Lee had beaten and repulsed General U.S. Grant during the Wilderness Campaign, which led him to consider

whether the Confederate commander would soon move against Crook with a vastly superior force. Having accomplished the major

part of his mission, destruction of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad as well as the magnificent New River bridge spanning

700-feet, Crook turned his two brigades north and after another hard march, reached and joined Averell's division at Union

on May 15th, and the division arrived at Meadow Bluff, West Virginia, on May 19th, thus concluding the expedition.

Brig. Gen. Averell, however, reported on May 15th that it was

the enemy that had advanced in three lines and pressed both flanks during a four hour engagement, but the vigor of the

enemy was gradually decreasing. At dark there was some prospect of our being able to drive him, but after dark he retired,

and I marched to Dublin, concluded Averell.

While in Union, Monroe County, WV, Averell said in his initial report to Crook, dated May 15, 1864, that

near Wytheville, VA, he had fought about 4,000 Rebels under Sam Jones for four hours, inflicting some loss and capturing

a few prisoners, and suffering the loss of 120 killed and wounded, and none missing. Averell had actually fought against

William E. Jones, as Sam Jones was not in command nor in state at the time. The cavalry commander would write a subsequent

report adjusting the size of the Confederate army to 5,000. The Union general failed to mention that he had suffered a minor

head wound during the battle and had it treated at a hospital.

The

battle near Wytheville, meaning Cove Mountain, was designed to occupy the enemy while allowing Crook to move his

division freely, according to Averell's reports. But the Union commander also reported the engagement as though

he simply made a demonstration before the enemy and then continued

checking the Rebel advances for four hours. To demonstrate or to occupy the

enemy is one matter, but suffering 120 casualties while reporting Confederate losses as few made it an unnecessary

and reckless fight. Averell, a graduate of West Point, understood that to occupy the enemy could have been

done easily with feints instead of hemorrhaging an army during four hours of fighting. Since Averell himself

reported the size of the enemy and casualties showing the one-sided losses of his command, with charges and counterassaults

during the four hour battle, it clearly indicates the movements of a general who was determined to destroy the enemy

and leave with at least one victory. But as Averell concluded in his report to command, it was dark and the enemy withdrew.

To his credit, his army had cut much track as well as occupy a large enemy force.

Although successful in saving the saltworks, May 10th had proven to be an omen for the Rebs, with "Stonewall"

Jackson dying one year prior to date, and on the following year, May 10, 1865, President Jefferson Davis would

be captured in Georgia while attempting to flee.

| Cove Mountain Civil War History |

|

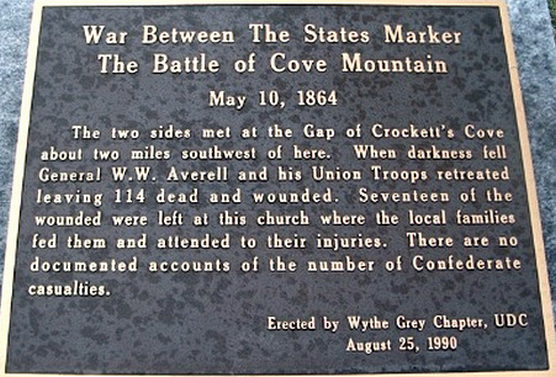

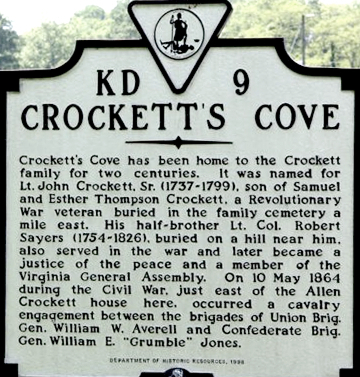

| Battle of Cove Mountain Marker |

| Crockett's Cove Historical Marker |

|

| Battle of Crockett's Cove Marker |

While Union Maj. Gen. George Stoneman (highest ranking Federal prisoner-of-war)

would soon move unopposed in the area as he burned and destroyed its infrastructure, Union cavalry commander, Phil Sheridan,

would destroy the remnants of Lt. Gen. Jubal Early's force in the Shenandoah Valley, and then return to assist Lee. Maj. Gen.

William Sherman, in concert, would turn his army north from Savannah and slice through the Carolinas as he moved closer

to linking up with Sheridan and Grant against Lee.

Analysis: Because Lt. Gen. Robert E. Lee ordered Gen.

Breckinridge to move three brigades totaling 4,000 men, 40% of his entire department, to Stanton, Virginia, immediately

in order to assist in the defense of that region, he is culpable for the outcome. Lee, after the fight at Cove Mountain expressed

concern in the increase of Union activity in the area. Some miles of the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad had been torn

asunder, the New River bridge had been burned only to fall as ambers in the river, and the obvious rout of the Confederate

force at Cloyd's Mountain.

Lee soon wrote to Secretary of State James A. Seddon asking who is in charge

of the department since the death of Jenkins? He wanted an experienced commander in the position. Lee had very tough

decisions to make on which front to protect, and although his dwindling forces were already stretched, the Confederate capital

of Richmond had to be protected at all hazards.

Seddon replied to Lee that Brig. Gen. William E. Jones had been commanding

the Department of Southwest Virginia in the absence of Breckinridge. Both points were partially correct. While Jones had a

supporting role in the defense of the region while he continued to command the neighboring Dept. of East Tennessee,

the name of the department Seddon gave was for another quasi-department that had little if any real command during the war.

If it wasn't bad enough for the Department of Western Virginia, it

was only going to get worse. Brig. Gen. William E. Jones would soon die while leading a charge in Virginia, and subsequently

most of the department would be moved to the Shenandoah Valley and Richmond areas.

While the department would soon marry the Department of East Tennessee,

it would be more on paper than anything else. Lee would soon be confronted with more reality as he would be forced to

reduce the now unified department to a token, skeleton force as he found himself requiring every available man to assist

in the defense of the capital during the Richmond-Petersburg Siege.

Lee had good cause to be concerned about

his flank, too, because it would later prove to be another highway for the Union army. The Confederate commander would

soon be pinned down in the Richmond-Petersburg trenches and require all available units to assist in the defense of the Confederate

capital, leaving the department void. And while Union Maj. Gen. George Stoneman (highest ranking Federal prisoner-of-war)

would go unopposed in the area as he burned and destroyed its infrastructure, Union cavalry commander, Phil Sheridan, would

erase the remnants of Lt. Gen. Jubal Early's force in the Shenandoah Valley, and then return to assist Grant. Maj. Gen. William

Sherman, in concert, would turn his army north from Savannah and slice through the Carolinas as he moved closer to linking

up with Sheridan and Grant against Lee.

What has hindered a more definitive history of this battle is that

both Confederate generals died shorty after the battle and without writing descriptive accounts or reports of the

engagement. Brig. Gen. William "Grumble" Jones would conclude his struggle for Southern independence while in battle

at Piedmont on June 5, less than one month after Cove Mountain. Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan would be killed while operating

in East Tennessee in September 1864. Jones, a graduate of West Point class of '48, was known for his hot temper, relentless

fighting spirit, and his opinion that a Southern soldier was worth two Northern men in battle. While he was leading a

charge at Piedmont, he was shot in the head and fell killed from atop his horse.

Known from history as one of the most daring cavalry raiders of the

Civil War, Morgan, who had concluded his famous raid of 1,000 miles through Indiana, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee in 1863,

had thence been fighting in southwestern Virginia, East Tennessee, Kentucky, and West Virginia. Morgan moved his command to the Union stronghold of East Tennessee following the Battle of

Cove Mountain on May 10th, and had been fighting the Union army only to meet his fate at Greeneville by being shot in

the back by a Union soldier on September 4th. On the evening of Sept. 3rd, Morgan had made his headquarters

at one Mrs. Williams' home in Greeneville. On Sept. 4th, Union Lt. Col. Ingerton, 13th Tennessee Cavalry, learned that

Morgan was at her home and detached a squadron under Capt. Wilcox, 13th TN. Cavalry, to surround the house and capture Morgan,

with his staff and escort, but Morgan was awakened by a nearby Confederate artillery piece, situated on College

Hill, that had fired a shot toward the squadron as they appeared in the street. He next exited the home and in attempt

to mount his horse, was shot in the back by Private Andrew Campbell, Company G, 13th Tenn. Cavalry. With the exception of

Morgan's death, the entire staff was captured that night.

(Sources and related reading below.)

Recommended

Reading: Lee's Endangered Left: The Civil War In Western Virginia, Spring Of 1864. From Kirkus Reviews: A competent, well-executed addition to the

ever-growing horde of Civil War literature, by Duncan (History/Georgetown University). The author reconsiders Union General

Ulysses S. Grants attempts to destroy the Confederates, led by General Robert E. Lee, at their traditional stronghold in western

Virginia and his efforts to threaten Lynchburg

during the spring and summer of 1864. Continued below…

The writing

here is crisp; refreshingly, our chronicler pays sharp attention to the effects of the campaign on civilians as the Union

army penetrated beyond its supply lines and came to live off the countryside in one of the Confederacy’s richest agricultural

regions, bringing home the harsh realities of war to civilians. The campaign swung back and forth, with Northern victories

at Cloyd's Mountain and New

River Bridge and Confederate routs at New Market, followed by a Union

failure to seize Lynchburg. Though the campaign proved costly

to the South, overall the Unions hope to capture the Shenandoah Valley foundered and the Confederates then went on to threaten

Washington, D.C. Duncan sensitively employs a wide variety of sources, military and civilian, to add to the coherence of his

account. Still, the books scope remains narrow, focusing on a not terribly glamorous period in the wars history; then, too,

wed do well to have the volume trimmed by a third. Duncan’s contention that the Unions

severity in dealing with civilian populations was directly reciprocated when the Confederates took Chambersburg,

Penn., creating a chain of vengeance that culminated when Sherman marched through the South, is insightfully argued, offering a fresh analysis to the

historical debate. Casual readers of the Civil War genre (and many die-hard buffs, as well) may want to leave this superbly

researched yet ultimately too specialized study for the historians to ponder. Includes 20 photographs.

Recommended

Reading: Saltville Massacre (Civil War Campaigns

and Commanders). Description: In October 1864, in the mountains of southwest Virginia,

one of the most brutal acts of the Civil War occurs. Brig. Gen. Stephen Burbridge launches a raid to capture Saltville. Included

among his forces is the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry. Repeated Federal attacks are repulsed by Confederate forces under the command

of Gen. John S. Williams. Continued below…

As the sun

begins to set, Burbridge pulls his troops from the field, leaving many wounded. In the morning, Confederate troops, including

a company of ruffians under the command of Captain Champ Ferguson, advance over the battleground seeking out and killing the

wounded black soldiers. What starts as a small but intense mountain battle degenerates into a no-quarter, racial massacre.

A detailed account from eyewitness reports of the most blatant battlefield atrocity of the war.

Recommended

Reading: From Winchester to Cedar Creek: The Shenandoah Campaign

of 1864. Amazon.com Review: Virginia's Shenandoah Valley was a crucial avenue for Confederate armies

intending to invade Northern states during the Civil War. Running southwest to northeast, it "pointed, like a giant's lance,

at the Union's heart, Washington, D.C.,"

writes Jeffry Wert. It was also "the granary of the Confederacy," supplying the food for much of Virginia. Both sides long understood its strategic importance, but not until the fall of

1864 did Union troops led by Napoleon-sized cavalry General Phil Sheridan (5'3", 120 lbs.) finally seize it for good. He defeated

Confederate General Jubal Early at four key battles that autumn. Continued below…

In addition

to a narrative of the campaign (featuring dozens of characters, including General George Custer and future president Rutherford

B. Hayes), this book is a study of command. Both Sheridan and Early were capable military leaders, though

each had flaws. Sheridan tended to make mistakes before battles,

Early during them. Wert considers Early the better general, but admits that few could match the real-time decision-making

and leadership skills of Sheridan once the bullets started

flying: "When Little Phil rode onto the battlefield, he entered his element." Early was a bold fighter, but lacked the skills

necessary to make up for his disadvantage in manpower. At Cedar Creek, the climactic battle of the 1864 Shenandoah campaign,

Early "executed a masterful offensive against a numerically superior opponent, only to watch it result in ruin." With more

Confederate troops on the scene, history might have been different. Wert relates the facts of what actually happened with

his customary clarity and insightful analysis.

Recommended Reading:

The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864 (Military Campaigns of the Civil War)

(416 pages) (The University of North Carolina Press). Description: The 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign is generally regarded as one of the most important

Civil War campaigns; it lasted more than four arduous months and claimed more than 25,000 casualties. The massive armies of

Generals Philip H. Sheridan and Jubal A. Early had contended for immense stakes... Beyond the agricultural bounty and the

boost in morale to be gained with its numerous battles, events in the Valley would affect Abraham Lincoln's chances for reelection

in November 1864. Continued below...

The eleven

essays in this volume reexamine common assumptions about the campaign, its major figures, and its significance. Taking advantage

of the most recent scholarship and a wide range of primary sources, contributors examine strategy and tactics, the performances

of key commanders on each side, the campaign's political repercussions, and the experiences of civilians caught in the path

of the armies. The authors do not always agree with one another, but, taken together, their essays highlight important connections

between the home front and the battlefield, as well as ways in which military affairs, civilian experiences, and politics

played off one another during the campaign.

Recommended Reading: The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864 (McFarland & Company). Description: A significant part of the Civil War was fought in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia,

especially in 1864. Books and articles have been written about the fighting that took place there, but they generally cover

only a small period of time and focus on a particular battle or campaign. Continued below...

This work covers

the entire year of 1864 so that readers can clearly see how one event led to another in the Shenandoah Valley and turned once-peaceful

garden spots into gory battlefields. It tells the stories of the great leaders, ordinary men, innocent civilians, and armies

large and small taking part in battles at New Market, Chambersburg, Winchester, Fisher’s

Hill and Cedar Creek, but it primarily tells the stories of the soldiers, Union and Confederate,

who were willing to risk their lives for their beliefs. The author has made extensive use of memoirs, letters and reports

written by the soldiers of both sides who fought in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864.

Recommended Reading: Shenandoah

Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Description:

Jubal A. Early’s disastrous battles in the Shenandoah Valley ultimately resulted in

his ignominious dismissal. But Early’s lesser-known summer campaign of 1864, between his raid on Washington and Phil

Sheridan’s renowned fall campaign, had a significant impact on the political and military landscape of the time. By

focusing on military tactics and battle history in uncovering the facts and events of these little-understood battles, Scott

C. Patchan offers a new perspective on Early’s contributions to the Confederate war effort—and to Union battle

plans and politicking. Patchan details the previously unexplored battles at Rutherford’s Farm and Kernstown (a pinnacle

of Confederate operations in the Shenandoah Valley) and examines the campaign’s influence

on President Lincoln’s reelection efforts. Continued below…

He also provides

insights into the personalities, careers, and roles in Shenandoah of Confederate General John C. Breckinridge, Union general

George Crook, and Union colonel James A. Mulligan, with his “fighting Irish” brigade from Chicago.

Finally, Patchan reconsiders the ever-colorful and controversial Early himself, whose importance in the Confederate military

pantheon this book at last makes clear. About the Author: Scott C. Patchan, a Civil War battlefield guide and historian, is

the author of Forgotten Fury: The Battle of Piedmont, Virginia, and a consultant and contributing writer for Shenandoah, 1862.

Review

"The author's

descriptions of the battles are very detailed, full or regimental level actions, and individual incidents. He bases the accounts

on commendable research in manuscript collections, newspapers, published memoirs and regimental histories, and secondary works.

The words of the participants, quoted often by the author, give the narrative an immediacy. . . . A very creditable account

of a neglected period."-Jeffry D. Wert, Civil War News (Jeffry D. Wert Civil War News 20070914)

"[Shenandoah

Summer] contains excellent diagrams and maps of every battle and is recommended reading for those who have a passion for books

on the Civil War."-Waterline (Waterline 20070831)

"The narrative

is interesting and readable, with chapters of a digestible length covering many of the battles of the campaign."-Curled Up

With a Good Book (Curled Up With a Good Book 20060815)

"Shenandoah

Summer provides readers with detailed combat action, colorful character portrayals, and sound strategic analysis. Patchan''s

book succeeds in reminding readers that there is still plenty to write about when it comes to the American Civil War."-John

Deppen, Blue & Grey Magazine (John Deppen Blue & Grey Magazine 20060508)

"Scott C. Patchan

has solidified his position as the leading authority of the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign with his outstanding campaign

study, Shenandoah Summer. Mr. Patchan not only unearths this vital portion of the campaign, he has brought it back to life

with a crisp and suspenseful narrative. His impeccable scholarship, confident analyses, spellbinding battle scenes, and wonderful

character portraits will captivate even the most demanding readers. Shenandoah Summer is a must read for the Civil War aficionado

as well as for students and scholars of American military history."-Gary Ecelbarger, author of "We Are in for It!": The First

Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862 (Gary Ecelbarger 20060903)

"Scott Patchan

has given us a definitive account of the 1864 Valley Campaign. In clear prose and vivid detail, he weaves a spellbinding narrative

that bristles with detail but never loses sight of the big picture. This is a campaign narrative of the first order."-Gordon

C. Rhea, author of The Battle of the Wilderness: May 5-6, 1864 (Gordon C. Rhea )

"[Scott Patchan]

is a `boots-on-the-ground' historian, who works not just in archives but also in the sun and the rain and tall grass. Patchan's

mastery of the topography and the battlefields of the Valley is what sets him apart and, together with his deep research,

gives his analysis of the campaign an unimpeachable authority."-William J. Miller, author of Mapping for Stonewall and Great

Maps of the Civil War (William J. Miller)

Sources: National Park Service; Official Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies; Major Thomas L. Broun's recollection of the battle of Cloyd's Mountain, Richmond, VA. 1909; Aleshire, Peter, The Fox

and the Whirlwind: General George Grook and Geronimo, Castle Books, 2000, ISBN 0-7858-1837-5; Bourke, John Gregory (1892).

On the Border with Crook. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 2007-07-08; Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J.,

Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3; Kennedy, Frances H., ed., The Civil War Battlefield

Guide, 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998, ISBN 0-395-74012-6: Magid,

Paul, "George Crook: From the Redwoods to Appomattox," University of Oklahoma Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0-8061-4207-4; Hoogenboom,

Ari (1995). Rutherford B. Hayes: Warrior & President; Robinson, Charles M., III. "General Crook and the Western Frontier",

Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001; Schmitt, Martin F., General George Crook, His Autobiography, University of Oklahoma

Press, 1986, ISBN 0-8061-1982-9; Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (February 1975). "National Register of Historic

Places Inventory / Nomination: Back Creek Farm". Virginia Department of Historic Resources; Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Blue:

Lives of the Union Commanders, Louisiana State University Press, 1960-4, ISBN 0-8071-0822-7; Whitman, John A., Historical

Facts About the Churches of Wythe County, Virginia, 1939.

|