|

Battle of Goldsboro Bridge

North Carolina and the Civil War

Battle of Goldsboro Bridge

Other Names: Goldsborough Bridge, Goldsboro Bridge, Goldsborough,

Goldsboro

Location: Wayne County

Campaign: Goldsboro Expedition, aka Goldsborough Expedition (December 1862)

Date(s): December 17, 1862

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. John G. Foster [US]; Brig. Gen Thomas Clingman [CS]

Forces Engaged: Department of North Carolina, 1st Division (10,000) [US];

Clingman’s Brigade (2,000) [CS]

Estimated Casualties: 220 total

Result(s): Union victory

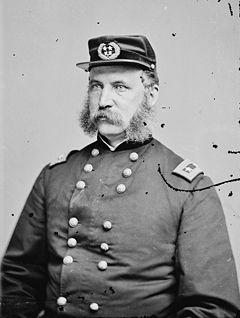

| General John G. Foster |

|

| (May 27, 1823 - September 2, 1874) |

| Battle of Goldsboro |

|

| Union (blue) and Confederate (red) armies at Goldsboro |

Summary: On Dec. 17, 1862, Foster’s expedition,

aka Goldsboro Expedition or Foster's Raid, reached the railroad near Everettsville and began destroying

the tracks north toward the Goldsboro Bridge (spelled Goldsborough at that time). Clingman's Brigade delayed the advance but was unable to prevent the destruction of the bridge.

His mission accomplished, Foster returned to New Bern where he arrived on the 20th. This battle was the high

water mark of the Goldsboro Expedition. It was also important because it demonstrated that the Union forces had

the ability to move from the North Carolina coast and push inland to the vital and strategic railroads

at Goldsboro.

Introduction: Union forces were under the command of

Brig. Gen. John G. Foster. A West Point graduate, Foster was a veteran of the Mexican-American War and proven brigade

commander during the recent Burnside Expedition. Confederate troops were commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas Lanier Clingman. A

former U.S. Senator from North Carolina,

Clingman was a lawyer, Fire-Eater, and one of the most outspoken politicians of his

era. His proslavery stance and position on states' rights, including the following quote, were well-known to

Congress: "Do us justice and we stand with you; attempt to trample on us and we

separate!" He initially commanded the 25th North Carolina Infantry, a unit popularized in the movie Cold Mountain starring Jude

Law as Private W. P. Inman (he really did exist). At General Lee's request, Clingman would later move his battle-hardened

brigade into the thick of the fight at Cold Harbor, where the unit would engage in a fierce contest before routing the

stubborn Federals.

Goldsboro hosted a major rail line for the Confederacy. The goal of the

Goldsboro Expedition was to capture the railroads in concert with Burnside's attack on General Lee at Fredericksburg

in 1862. The Atlantic and North Carolina railroad intersected at Goldsboro with the Wilmington and Weldon railroad (the lifeline

of General Lee's Army of Northern Virginia). Foster attacked Goldsboro in December 1862, burned the railroad bridge, but did

not actually take the town. Upon burning the bridge, Foster and his troops left for New Bern. The railroad was halted, but

only briefly, and enough of the bridge was left intact to repair.

| Battle of Goldsboro Bridge and Foster's Raid |

|

| Battle of Goldsboro and Foster's Raid |

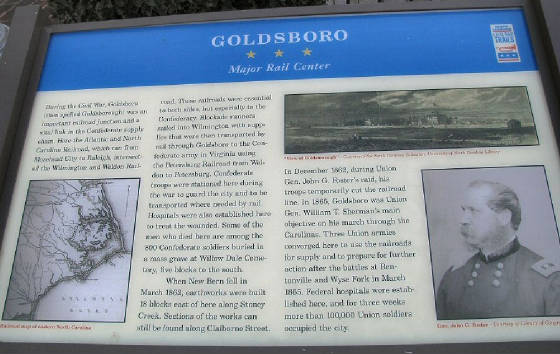

| Battle of Goldsboro: A Major Rail Center |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

| NC Civil War Battlefields |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

Background: The Battle of Goldsboro Bridge was contested December

17, 1862, at the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad Bridge across the Neuse River, three miles south of Goldsboro, North Carolina. Troops and supplies aboard

trains from the Deep South and the port at Wilmington had to cross this bridge on their way to Virginia, making this bridge

a vital link in the Confederate supply chain. Because of the intersection of two railroads at Goldsboro, the Wilmington &

Weldon and the Atlantic & North Carolina, that city had become one of the most important railroad centers in the South.

There were other railroad bridges and depots between Wilmington and Virginia,

but the presence of the two railroads at Goldsboro, with the fact that Goldsboro was only 60 miles from Union-occupied New Bern, made the railroad bridge at Goldsboro an important objective for the Union War Department. Union commanders believed that

the destruction of this bridge would impact the ability of the Confederacy to wage war, if completed in conjunction with a

major Union victory in Virginia. A defeated Confederate army, denied re-supply, could be swept aside, leaving the Confederate

capital at Richmond vulnerable.

The time to implement this plan arrived late in 1862. In December,

the commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, General Ambrose E. Burnside, was planning an attack on General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Plans were developed for the Union commander in North Carolina,

General John G. Foster, to simultaneously launch an attack from New Bern against the railroad bridge at Goldsboro. This expedition

has come to be known as Foster’s Raid.

| Location of the Battle of Goldsboro Bridge |

|

| Civil War Battle of Goldsboro Bridge, North Carolina |

| "The Goldsboro Generals" |

|

| North Carolina Civil War History |

Battle: On

the morning of December 11, 1862, General Foster marched from New Bern with a force of 10,000 infantry, 640 cavalry and 40

guns. After meeting and defeating small Confederate forces at Southwest Creek, Kinston and White Hall, Foster’s army arrived at the railroad bridge south of Goldsboro on the

morning of December 17. Foster deployed his troops and artillery and they began to fight their way to the bridge.

(Right) Foster, Clingman, and Evans. Principal figures at Goldsboro Bridge.

The bridge was defended by General Thomas Clingman, who commanded a small force of some 2,000 men and a dozen guns. The Confederates

fought valiantly but were repulsed east of the railroad and to the north bank of the Neuse River. After a two hour battle,

a daring assault party of Union volunteers, supported by artillery fire, rushed forward amidst a hail of bullets and set fire

to the bridge. Union artillery subsequently fired on the burning bridge, to aid in its destruction and to foil Confederate

attempts to douse the flames. In a short while the bridge was destroyed, and then Union troops further damaged the railroad

by destroying the tracks for a distance of two to three miles south from the bridge.

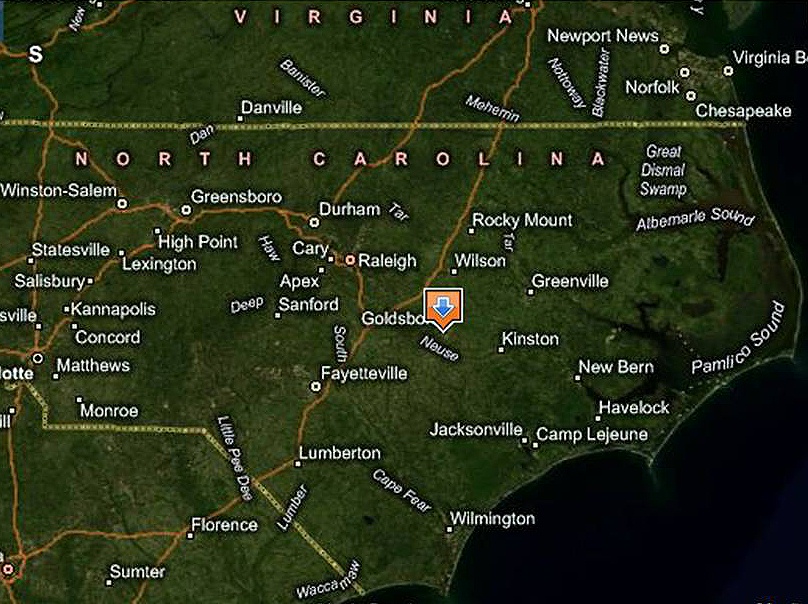

| Location of Goldsboro, North Carolina |

|

| Satellite Map Courtesy Microsoft Virtual Earth (3D) |

| Battle of Goldsboro Bridge Timeline |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

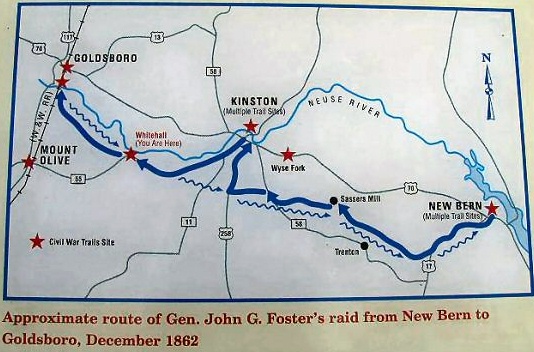

| From New Bern to Goldsboro |

|

| Route of General Foster from New Bern to Goldsboro |

Late in the afternoon

the Union troops, their objective met, formed and began the long march towards their base at New Bern, leaving one brigade

of infantry and one battery of artillery as a rear guard to cover their withdrawal. On the north bank of the river, Confederate

forces had been reinforced and for the first time actually outnumbered the Union contingent that remained on the

field. At a council of war, Confederate General Nathan Evans, who had now arrived with a portion of his command, ordered Clingman

to cross to the south bank of the river via the county wagon bridge, located one half mile upriver from the burned railroad

bridge, and attack the Union rear guard. Pursuant to this order, Clingman led his brigade, Clingman's Brigade, which consisted of four North Carolina infantry regiments, the 8th, 31st, 52nd and 61st, across the bridge, supported

by other troops from North Carolina, South Carolina and Mississippi. Clingman posted the 31st and 52nd North Carolina Regiments

near the river bank and hurried one mile to the south with the 8th and 61st. At this point, Evans arrived on the south bank

of the river and ordered the 31st and 52nd to attack across the railroad and engage the Union rear guard. These two regiments

formed-up and crossed a cultivated field west of the railroad, then climbed the high railroad embankment. After pausing briefly

at the top, they streamed down the eastern face of the embankment shouting the rebel yell, and appearing to

one startled Union soldier like “immense gray ants.”

The sound of the

Confederate attack attracted the attention of Union troops that had just left the field and before the North Carolinians could

reach the Federal position, additional Union soldiers and guns had rushed back onto the field. In a short time the Union command

had grown into two infantry brigades and three batteries of artillery and the odds were suddenly against the Confederate attackers.

When within 100 yards of the Union line the Confederates were met with musketry and double canister fire from up to eighteen

Federal guns, and the Confederates were turned back with heavy losses. Clingman’s other two units, the 8th and

61st North Carolina, were now in position but wisely did not cross the railroad, and instead engaged Union forces from behind

the embankment.

It was now quite late and as darkness descended on the battlefield the firing

died down. The Battle of Goldsboro Bridge concluded with nearly 250 men killed, wounded and missing. Foster’s army

once more turned to leave the field but was slowed by having to cross the freezing waters of a swollen stream--which flowed

behind the Union positions. During their counterattack, Rebel soldiers had destroyed the dam on a millpond through which the

stream flowed in an effort to trap the Yankee rear guard. Now Union soldiers were compelled to cross the rapidly rushing stream,

which was up to their necks. After crossing the stream, the soaked soldiers set fire to the woods on both sides of their line

of march, to warm themselves and light their way in the darkness. The Union army returned to New Bern just before

Christmas 1862. They left in their wake a torn and broken landscape, and 1,300 combined Union and Confederate casualties.

| Intense Confederate musketry from the woods |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

| Civil War at Goldsboro Bridge |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

Results: Foster’s Raid was a tactical success

for the Union. The vital railroad bridge near Goldsboro was destroyed, temporarily halting the flow of supplies from the Deep

South and the port at Wilmington to Virginia. Clingman, hearing of a possible censure by State legislatures for his failure

to prevent the burning, wrote to Gov. Zeb Vance, January 28, 1863, saying, "It is said that the troops in the vicinity

of Goldsboro ought to have prevented the loss of the bridge & the damage done to the railroad. This is undoubtedly true.

You are aware, as well as I am, for we had a conversation on the day following

that at least six hours before the bridge was burnt, there was a brigade in Goldsboro, & within three miles of the railroad

bridge. Had these troops not to speak of others there present, been moved to my support, I cannot permit myself to doubt,

but that we should have defended the bridge."

The success Foster enjoyed at Goldsboro was muted, however, by events in

Virginia. Burnside’s attack against Lee at Fredericksburg was a disaster for the Union (which was soundly defeated).

The triumphant Confederate army in Virginia was thus able to withstand

a temporary loss of supplies and reinforcements from the South, nullifying what would have otherwise

been a major strategic victory for the Union.

Because of the importance of

the Goldsboro Bridge to the Confederate chain of supply, men and engineers were rushed to the site and the bridge was rebuilt

in a matter of weeks. The next time the Union army would get so close to Goldsboro was on March 21, 1865, when three Union

armies over 100,000 strong, captured the city and its vital railroad bridge and depots. These Union armies, commanded

by Generals William T. Sherman, Alfred Terry and John Schofield, used the railroads at Goldsboro to re-supply for a final

push on the state capital at Raleigh, which was to be followed by a link-up with General U. S. Grant’s army in Virginia.

The three armies left Goldsboro on April 10, 1865; just one day after General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

Sources: National Park Service; goldsboroughbridge.com;

Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; National Archives; Library of Congress; Zebulon Baird Vance Papers,

Private Collections, State Archives of North Carolina.

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in the Carolinas

(Hardcover). Description: Dan Morrill relates the experience

of two quite different states bound together in the defense of the Confederacy, using letters, diaries, memoirs, and reports.

He shows how the innovative operations of the Union army and navy along the coast and

in the bays and rivers of the Carolinas affected the general course of the war as well as

the daily lives of all Carolinians. He demonstrates the "total war" for North

Carolina's vital coastal railroads and ports. In the latter part of the war, he describes

how Sherman's operation cut out the heart of the last stronghold

of the South. Continued below...

The author

offers fascinating sketches of major and minor personalities, including the new president and state governors, Generals Lee,

Beauregard, Pickett, Sherman, D.H. Hill, and Joseph E. Johnston. Rebels and abolitionists, pacifists and unionists, slaves

and freed men and women, all influential, all placed in their context with clear-eyed precision. If he were wielding a needle

instead of a pen, his tapestry would offer us a complete picture of a people at war. Midwest Book Review: The Civil War in the Carolinas by civil war expert and historian

Dan Morrill (History Department, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, and Director of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historical

Society) is a dramatically presented and extensively researched survey and analysis of the impact the American Civil War had

upon the states of North Carolina and South Carolina, and the people who called these states their home. A meticulous, scholarly,

and thoroughly engaging examination of the details of history and the sweeping change that the war wrought for everyone, The

Civil War In The Carolinas is a welcome and informative addition to American Civil War Studies reference collections.

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in North Carolina. Description: Numerous

battles and skirmishes were fought in North Carolina during

the Civil War, and the campaigns and battles themselves were crucial in the grand strategy of the conflict and involved some

of the most famous generals of the war. John Barrett presents the complete story of military engagements across the state,

including the classical pitched battle of Bentonville--involving Generals Joe Johnston and William Sherman--the siege of Fort Fisher, the amphibious

campaigns on the coast, and cavalry sweeps such as General George Stoneman's Raid.

Recommended Reading: Ironclads and Columbiads: The Coast

(The Civil War in North Carolina) (456 pages). Description: Ironclads and Columbiads covers some of the most

important battles and campaigns in the state. In January 1862, Union forces began in earnest to occupy crucial points on the

North Carolina coast. Within six months, Union army and

naval forces effectively controlled coastal North Carolina from the Virginia

line south to present-day Morehead City.

Continued below...

Union setbacks in Virginia, however, led to the withdrawal of many federal

soldiers from North Carolina, leaving only enough Union troops to hold a few coastal strongholds—the vital ports and

railroad junctions. The South during the Civil War, moreover, hotly contested the North’s ability to maintain its grip

on these key coastal strongholds.

Recommended Reading: Storm

over Carolina: The Confederate Navy's Struggle for Eastern North Carolina. Description: The struggle for control of the eastern

waters of North Carolina during the War Between the States

was a bitter, painful, and sometimes humiliating one for the Confederate navy. No better example exists of the classic adage,

"Too little, too late." Burdened by the lack of adequate warships, construction facilities, and even ammunition, the

South's naval arm fought bravely and even recklessly to stem the tide of the Federal invasion of North

Carolina from the raging Atlantic. Storm

Over Carolina is the account of the Southern navy's struggle in North

Carolina waters and it is a saga of crushing defeats interspersed with moments of brilliant and even

spectacular victories. It is also the story of dogged Southern determination and incredible perseverance in the face

of overwhelming odds. Continued below...

For most of

the Civil War, the navigable portions of the Roanoke, Tar, Neuse, Chowan, and Pasquotank rivers were

occupied by Federal forces. The Albemarle and Pamlico sounds, as well as most of the coastal towns and counties, were also

under Union control. With the building of the river ironclads, the Confederate navy at last could strike a telling blow against

the invaders, but they were slowly overtaken by events elsewhere. With the war grinding to a close, the last Confederate vessel

in North Carolina waters was destroyed. William T. Sherman

was approaching from the south, Wilmington was lost, and the

Confederacy reeled as if from a mortal blow. For the Confederate navy, and even more so for the besieged citizens of eastern

North Carolina, these were stormy days indeed. Storm Over Carolina describes their story, their struggle, their history.

Recommended Reading: Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War (Studies in Maritime History Series). From Library Journal: From the profusion of books

about Confederate blockade running, this one will stand out for a long time as the most complete and exhaustively researched.

Though not unaware of the romantic aspects of his subject, Wise sets out to provide a detailed study, giving particular attention

to the blockade runners' effects on the Confederate war effort. Continued below...

It was, he finds, tapping hitherto unused sources, absolutely essential, affording the South a virtual lifeline

of military necessities until the war's last days. This book covers it all: from cargoes to ship outfitting, from individuals

and companies to financing at both ends. An indispensable addition to Civil War literature.

Try the Search Engine for Related Studies: Battle of Goldsboro Bridge,

Battle of Goldsborough Bridge, Goldsboro Expedition North Carolina Civil War, General John Foster, General Thomas Clingman,

Clingman's Brigade, Department of North Carolina

|