|

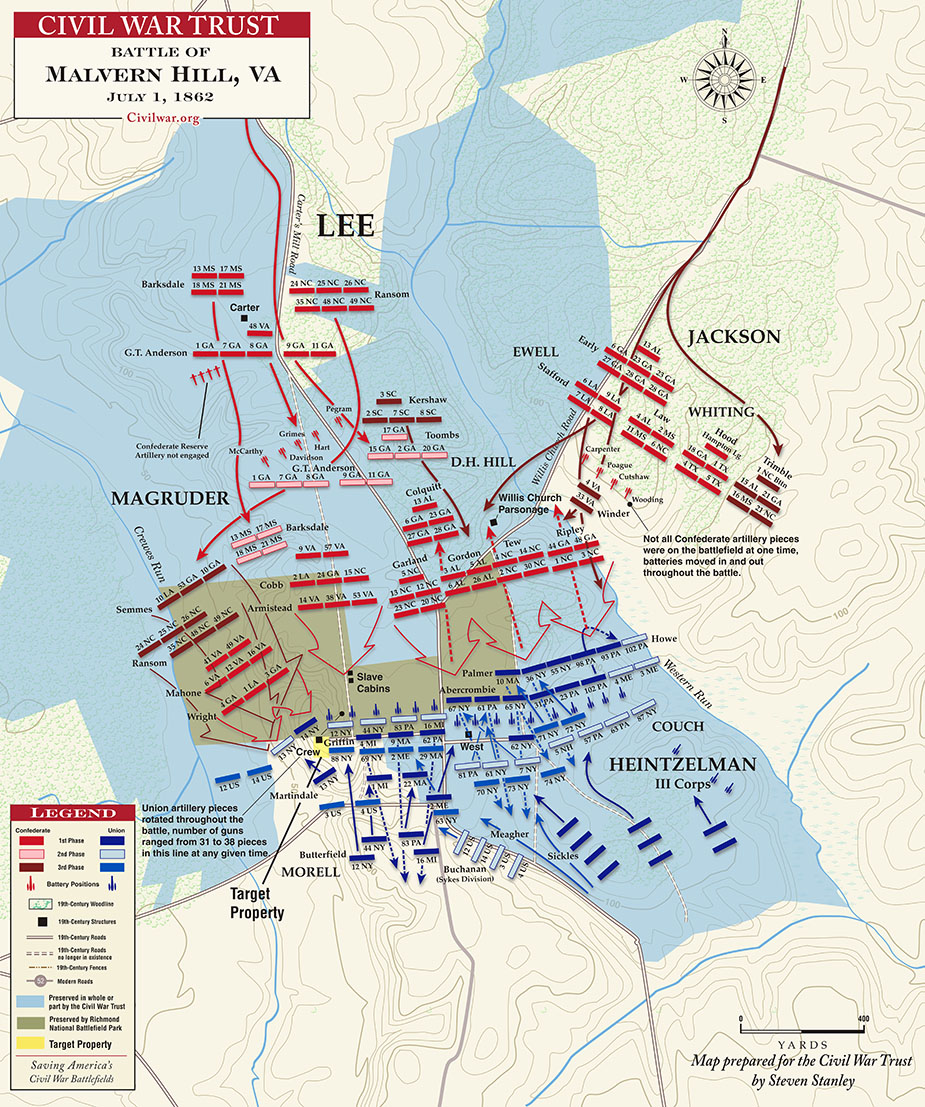

Battle of Malvern Hill, Virginia

Malvern Hill and the American Civil War

Battle of Malvern Hill

Other Names: Battle of Poindexter’s Farm

Location: Henrico County

Campaign: Peninsula Campaign (March-July 1862)

Date(s): July 1, 1862

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan [US]; Gen. Robert E. Lee [CS]

Forces Engaged: Armies

Estimated Casualties: 8,500 total (US 3,200; CS 5,300)

Result(s): Union victory

Introduction: During the American Civil War

(1861-1865), battles generally unfolded as the result of an objective in a campaign, expedition, and so on.

Malvern Hill was no different. It was the final battle fought near Richmond, VA., July 1, 1862, during the Peninsula

Campaign, and, while each side had almost an equal number of troops, the Union army enjoyed an advantage with its 250 artillery

pieces. This fight pitted determined Confederate infantry against dogged Federal artillery. It also squared the two armies,

the Union army entrenched on the slopes while the Confederates conducted ill-fated and disjointed frontal assaults by

crossing exposed terrain and marching up the slopes hoping to dislodge the enemy that was more than jubilant to welcome

the visitors with artillery shot and shell.

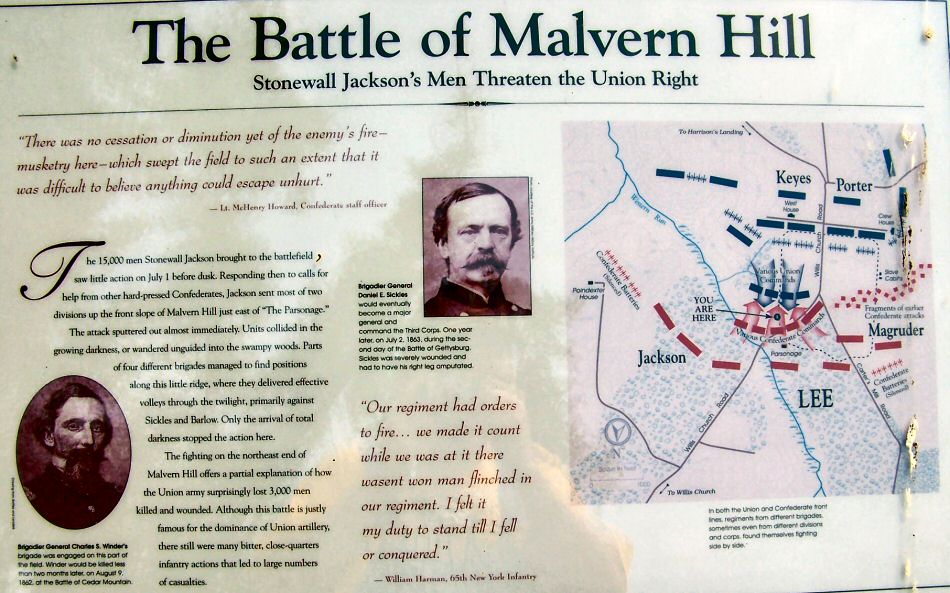

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

|

| Result of canister ball head shot |

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

|

| 12-pounder canister shot |

In early April 1862, Maj. Gen. George McClellan, having landed his

troops at Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, began to move slowly toward Yorktown. Gen. Joe Johnston's plan

for the defense of the Confederate capitol was controversial. Knowing that his army was half the size of McClellan's and that

the Union Navy could provide direct support to McClellan from either river, Johnston attempted to convince Confederate President

Jeff Davis and Gen. Robert E. Lee that the best course would be to concentrate in fortifications around Richmond, the Confederate

capitol. He was unsuccessful in persuading them and deployed most of his force on the Peninsula. Following lengthy siege preparations

by McClellan at Yorktown, Johnston withdrew and fought a sharp defensive fight at Williamsburg, May

5, and turned back an attempt at an amphibious turning movement at Eltham's Landing on May 7. By late May the Union army was

within six miles of Richmond.

Realizing that he could not defend Richmond forever from the Union's overwhelming

numbers and heavy siege artillery and that McClellan's army was divided by the rain-swollen Chickahominy River, Johnston attacked

south of the river on May 31 in the Battle of Seven Pines or Fair Oaks. His plan was aggressive, but too complicated for his

subordinates to execute correctly, and he failed to ensure they understood his orders in detail or to supervise them closely.

The battle was tactically inconclusive, but it stopped McClellan's advance on the city and would turn out to be the high-water

mark of his invasion. More significant, however, was that Johnston was wounded by an artillery shell on the second day of

the battle, hit in his right shoulder and chest. This led to Davis turning over command to the more aggressive Robert E. Lee,

who would lead the Army of Northern Virginia for the rest of the war. Lee began by driving McClellan from the Peninsula during

the Seven Days Battles of late June and beating a Union army a second time near Bull Run in August. For the following

narrative, the use of numerous maps and markers complement the fight at Malvern Hill.

(Right) Headshot caused by a single iron canister ball fired from

the 12-pounder field howitzer. Some 250 Union cannon, including field howitzers, were concentrated at Malvern Hill,

making it one of the largest artillery battles of the war. This skull was discovered

in 1876 on another battlefield, Morris Island, South Carolina, near the site of Battery Wagner, an earthwork fort that

had protected the entrance to Charleston Harbor during the Civil War. The skull belonged to a man of African descent—a

soldier of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers, which had led the assault on Wagner during the night of July 18, 1863. From

the size of the wound, and the remains of the projectile itself, it can be determined what type of munition hit this man:

an iron canister ball from one of two 12-pounder field howitzers known to have been used in the repulse of that attack. Of greater intensity was the cannonading at Malvern Hill, which was so loud

that people living 100 miles away claimed to have heard it.

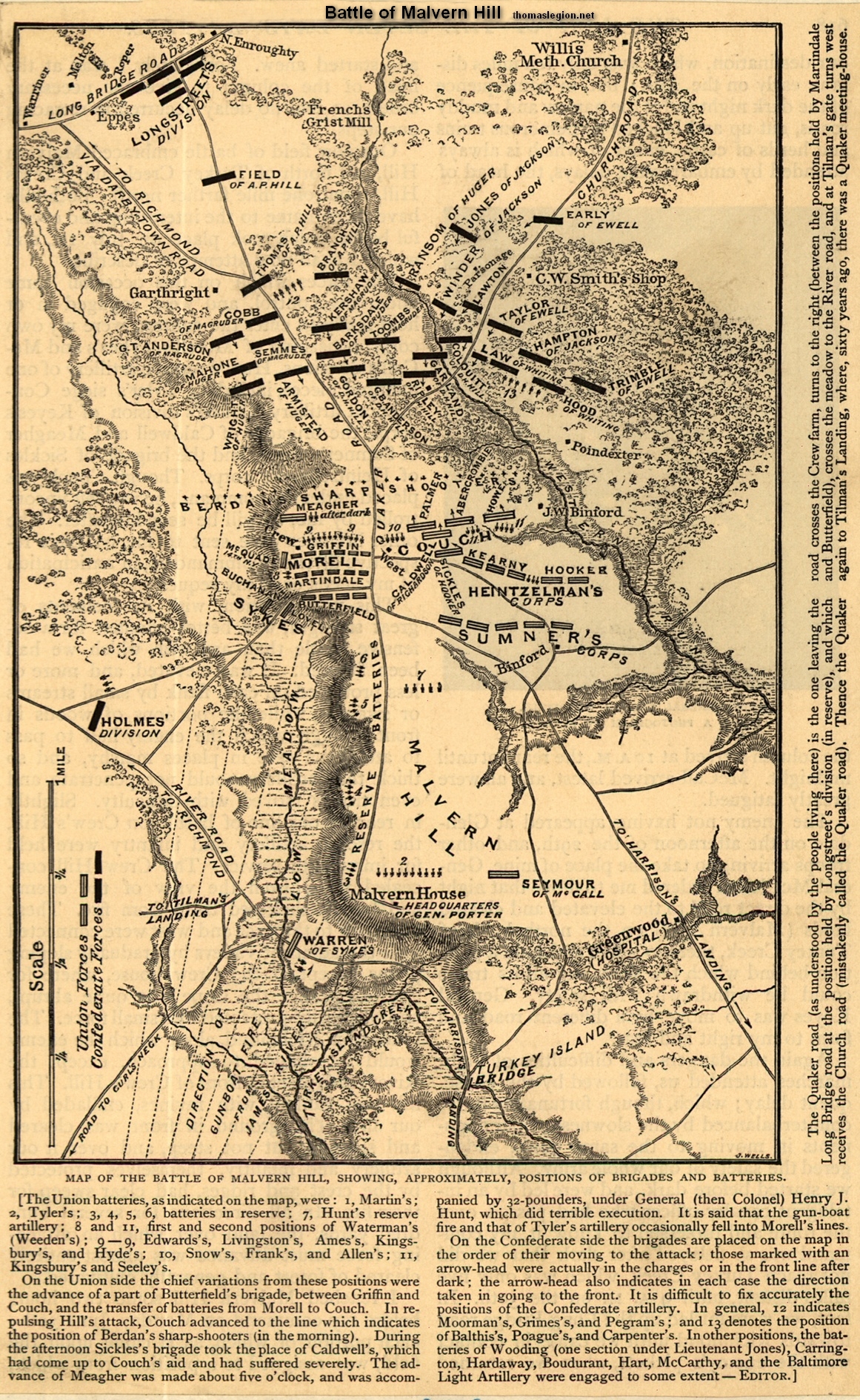

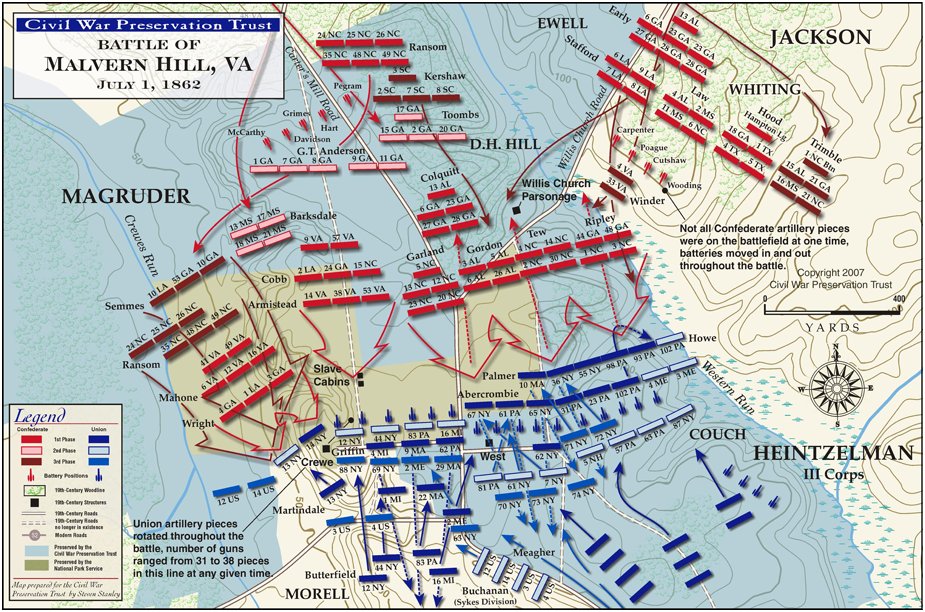

| Battle of Malvern Hill Map |

|

| Battle of Malvern Hill and Union and Confederate Battlefield Positions |

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

|

| Map of Union and Confederate Battlefield Positions at Malvern Hill |

Summary: The Battle of Malvern Hill, also known as

the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, was the sixth and last of the Seven Days Battles. On July 1, 1862, Gen. Robert E. Lee, having replaced the wounded Gen. Joe Johnston, launched

a series of disjointed assaults on the nearly impregnable Union position on Malvern Hill. The Confederates suffered more than

5,300 casualties without gaining an inch of ground. Despite his victory in the lopsided fight, McClellan withdrew to entrench

at Harrison’s Landing on James River, where his army was protected by gunboats. This also ended the Peninsula Campaign. When McClellan’s army ceased to threaten Richmond, Lee sent Jackson

to operate against Maj. Gen. John Pope’s army along the Rapidan River, thus initiating the Northern Virginia Campaign.

Although Malvern Hill was the last of the Seven Days Battles and a Union victory, McClellan's

career would never recover because, like previous battlefield successes, he displayed the inability to follow-up

and pursue the defeated and retreating Southerners. But Lee's status was elevated because he had saved the Confederate

capitol of Richmond. For his mettle in the Seven Days Battles, the public perception of Lee had changed from "Granny

Lee" to "Marse Lee." Confederate Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill, however, said that "Malvern

Hill wasn't war; it was murder."

Background: In spring 1862, Union commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan developed an ambitious plan

to capture Richmond, the Confederate capitol, on the Virginia Peninsula. His 121,500-man Army of the Potomac, along with 14,592

animals, majority being horses, 1,224 wagons and ambulances, and 44 artillery batteries, would load onto 389 vessels

and sail to the tip of the peninsula at Fort Monroe, then move inland and capture the capitol. The bold and sweeping landing

was executed with few incidents, but the Federals were delayed for about a month during the Siege of Yorktown. When McClellan's

army finally attacked on May 4, the defensive earthworks around Yorktown were undefended. After some hours, the Army

of the Potomac pursued the retreating Confederates. When Union troops encountered the Confederate rearguard at Williamsburg,

the two armies fought an inconclusive battle. The Confederates continued their withdrawal that night. To stymie the Southerners'

retreat, McClellan sent Brig. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith to Eltham's Landing by boat, resulting in a battle there on May

7. When the Union Army tried to attack Richmond by way of the James River, they were turned back at Drewry's Bluff on May

15. All the while, McClellan continued his pursuit of Confederate forces, who were withdrawing quickly towards Richmond.

The lack of decisive action on the Virginia Peninsula spurred President Abraham

Lincoln to order McClellan's army to move into positions close to Richmond. By May 30, McClellan had begun moving troops across

the Chickahominy River, the only major natural barrier that separated his army from Richmond. However, heavy rains and thunderstorms

on the night of May 30 caused the water level to swell, washing away two bridges and splitting the Federal army in two across

the Chickahominy. In the subsequent Battle of Seven Pines, Confederate general-in-chief Joseph E. Johnston sought to capitalize

on the bifurcation of McClellan's army, attacking the half of the Union Army that was stuck south of the river. Johnston's

plan fell apart, and McClellan lost no ground. Late in the battle, Johnston was hit in the right shoulder by a bullet and

in the chest by a shell fragment; his command went to Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith. Smith's tenure as commander of the Army

of Northern Virginia was short. On June 1, after an unsuccessful attack on Union forces, Jefferson Davis, a former U.S. Secretary

of War turned President of the Confederacy, appointed Robert E. Lee, his own military adviser, to replace Smith as the

commander-in-chief of the Confederate armies.

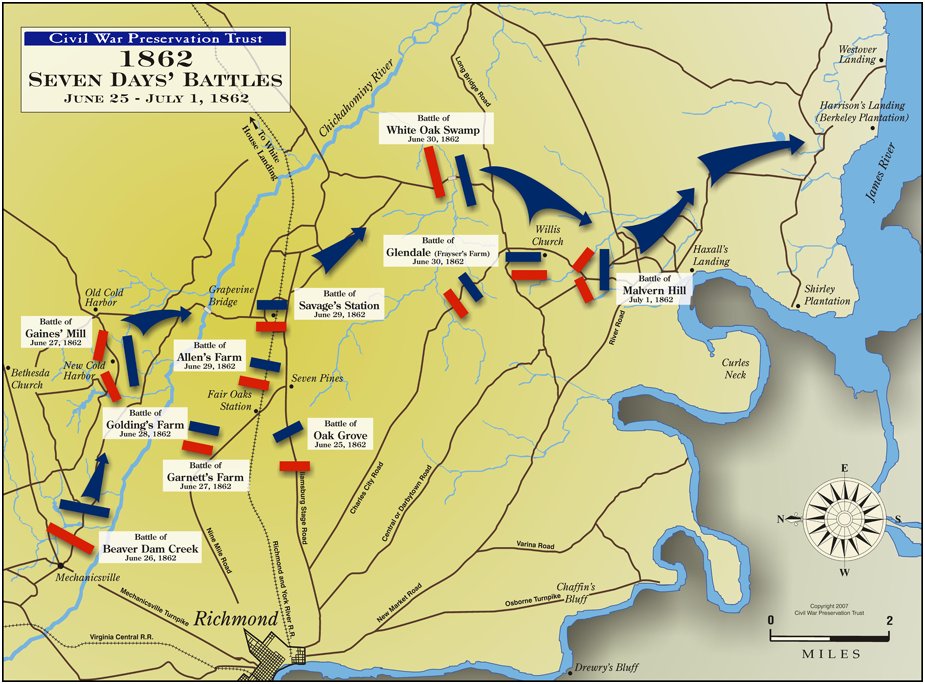

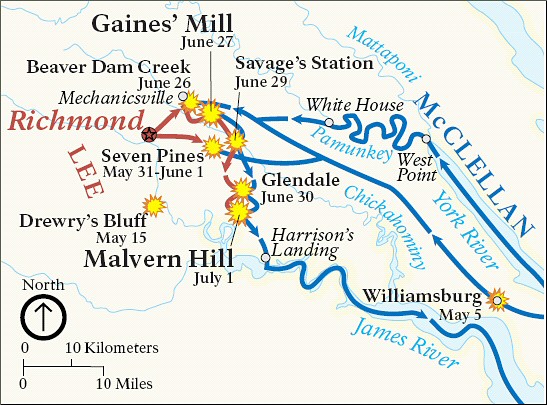

The subsequent two weeks on the peninsula were mostly quiet. On June 25, though,

a surprise attack by McClellan began a series of six major battles over the next week near Richmond—the Seven Days Battles.

On the first day, as Lee led the Army of Northern Virginia toward the Union lines, McClellan preempted him with an attack

at Oak Grove. Lee's men successfully warded off the Union assault, and Lee continued with his plans. The next morning, the

Confederates attacked the Army of the Potomac at Mechanicsville. Union forces turned back the Confederate onslaught, inflicting

heavy losses. After Mechanicsville, McClellan's army withdrew to a position behind Boatswain's Swamp. There, on June 27, the

Union soldiers suffered another Confederate attack, this time at Gaines's Mill. In the resulting battle, the Confederates

launched numerous failed charges, until a final concerted attack broke the Union line, resulting in the only clear Confederate

victory during the Seven Days. The action at Garnett's and Golding's Farm, fought next, was merely a set of skirmishes. Lee

attacked the Union Army at the Battle of Savage's Station on June 29 and the battles of Glendale and White Oak Swamp June

30, but all three battles were inconclusive. After this series of conflicts that inflicted thousands of casualties on both

armies, McClellan began to position his forces to an imposing natural position atop Malvern Hill.

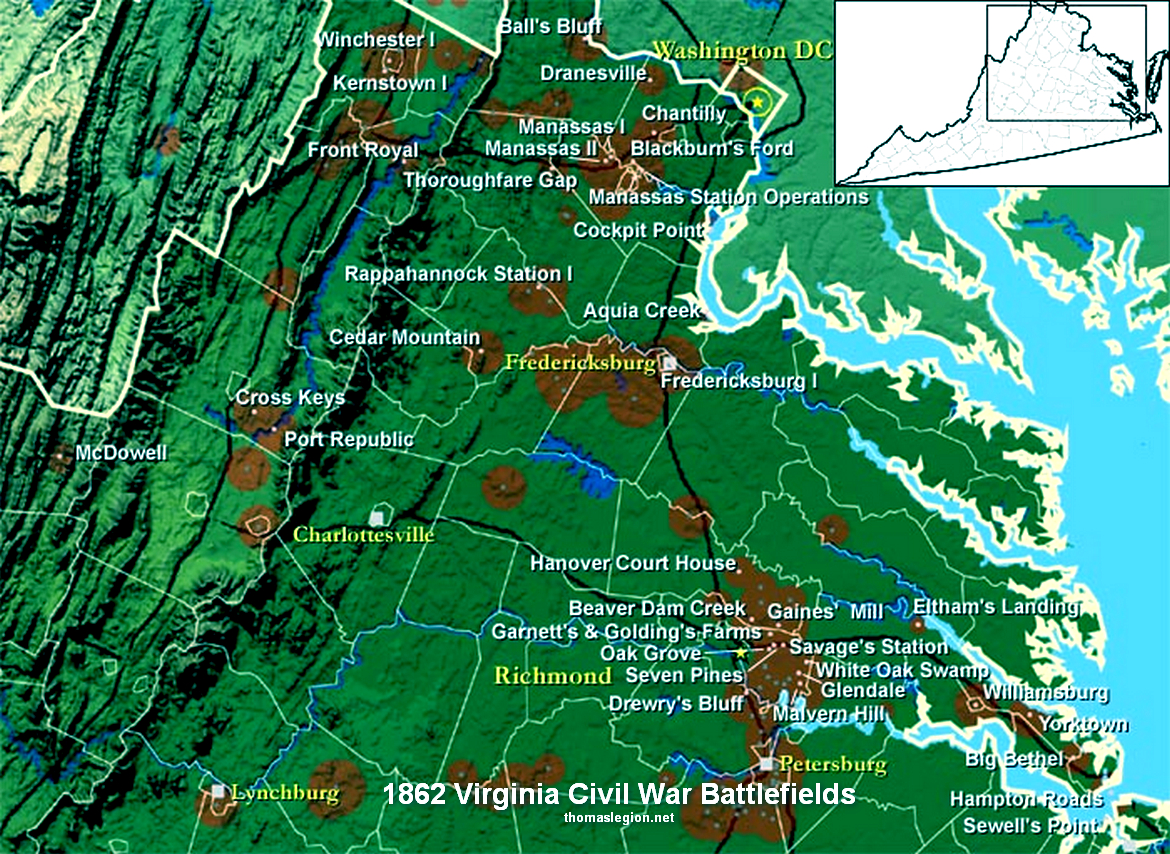

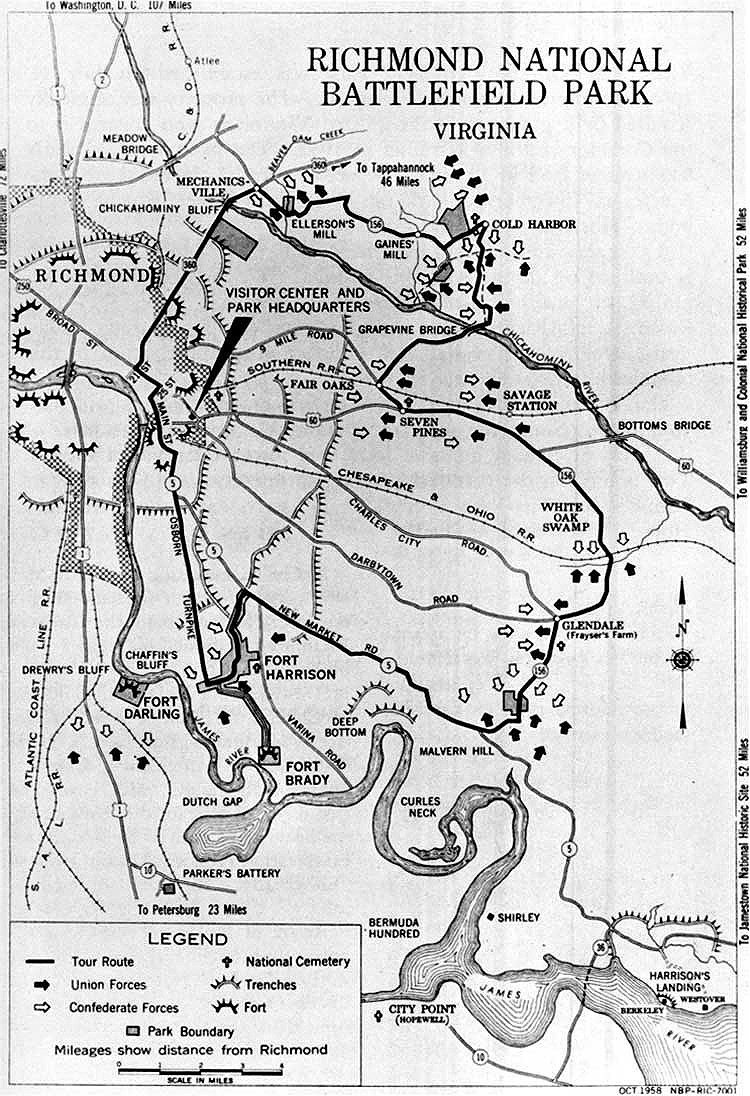

| Map of 1862 Virginia Civil War Battlefields |

|

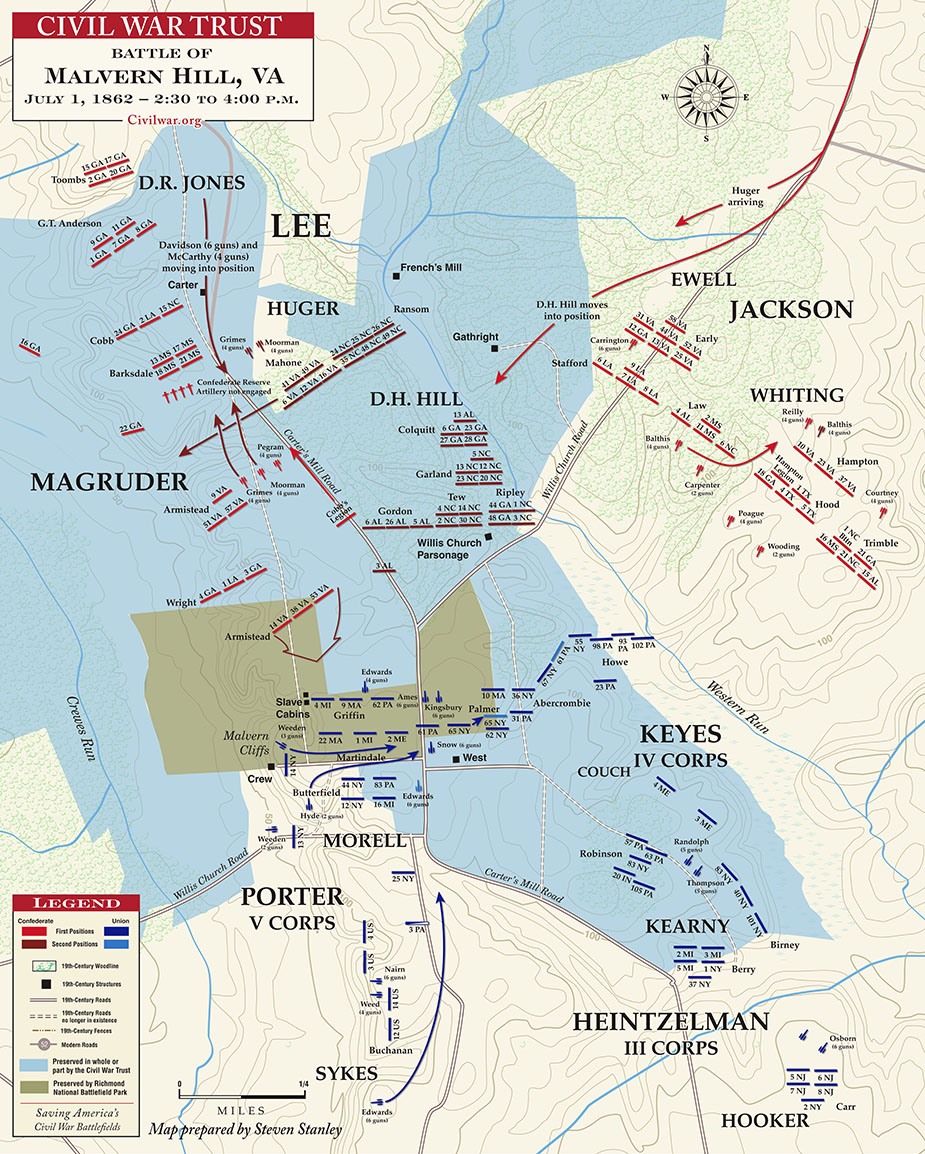

| Digitally Enhanced Map of Battle of Malvern Hill |

Prelude: A few days prior to the action on Malvern Hill,

McClellan incorrectly believed that the Army of the Potomac was vastly outnumbered by its Confederate foe, and his fear of

being cut off from his supply depot left him cautious and wary. On the night of June 28, 1862, McClellan told his generals

that he intended to move his army to a position on the north bank of the James River called Harrison's Landing, where they

would be protected by Union gunboats. The Army of the Potomac came to Malvern Hill, the army's final stop before reaching

the Landing, with approximately 54,000 men.

On the morning of June 30, the Union V Corps under Fitz John Porter,

a part of McClellan's Army of the Potomac, amassed atop Malvern Hill. Col. Henry Hunt, McClellan's skilled chief of artillery,

posted 171 guns on the hill and 91 more in reserve in the south. The artillery line on the hill's slope consisted of eight

batteries of field artillery with 37 guns. Brig. Gen. George Sykes's division would guard the line. In reserve were additional

field artillery and three batteries of heavy artillery, which included five 4.5-inch Rodman guns, five 20-pounder Parrott

rifles and six 32-pounder howitzers. As more of McClellan's forces arrived at the hill, Porter continued to reinforce the

Union line. Brig. Gen. George Morell's units, stationed between the Crew and West farms, extended the line to the northeastern

section. Brig. Gen. Darius Couch's division of the IV Corps, as yet unbloodied by the skirmishes of the Seven Days, further

extended the northeastern line. This left 17,800 soldiers from Couch's and Morell's divisions at the northern face of the

hill, overlooking the Quaker Road, from which the Federals expected Lee's forces to attack.

Early the next day, Tuesday, July 1, McClellan, having come from nearby

Haxall's Landing the night before, examined his army's battle line on Malvern Hill. His inspection left him worried most about

the Union Army's right (eastern) flank, which lay behind Western Run. Western Run was an area necessary for McClellan's plans

to relocate to Harrison's Landing, and he feared an attack might come from there. As a result, he posted the largest portion

of his army there: two divisions from Edwin Sumner's II Corps, two divisions from Brig. Gen. Samuel P. Heintzelman's III Corps,

two divisions from Brig. Gen. William Franklin's VI Corps and one division from Maj. Gen. Erasmus Keyes's IV Corps, who were

stationed across the James. The division under Brig. Gen. George McCall, badly damaged in the fighting at Glendale with McCall

himself wounded and captured, was held in general reserve. McClellan did

not believe his army was ready for a battle, and hoped that Lee would not give them one. Nonetheless, he left his troops at

Malvern Hill and traveled downstream aboard the ironclad USS Galena to inspect his army's future resting place at

Harrison's Landing. McClellan did not delegate an interim commander; Porter, who was in command during the initial attack,

became the de facto leader on the Union side of the battle.

With some 55,000 soldiers, the Army

of Northern Virginia was practically par with the Federals, and with Lee

at the helm, notably more aggressive. He wanted a final, decisive attack that would effectively scatter the invading Federals.

Several pieces of evidence—abandoned commissary stores, wagons and arms, and the hundreds of Union stragglers and deserters

his units had happened upon and captured—led Lee to conclude that the Army of the Potomac was demoralized and retreating.

Altogether—the battles leading up to Malvern Hill—Lee's plans to destroy the Federal army had failed for one reason

or another. Though he was undeterred, his chances for decisive victory were diminishing quickly.

| Malvern Hill and Seven Days Battles. |

|

| Malvern Hill and Seven Days Battles. Courtesy Civil War Preservation Trust |

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

|

| Watercolor of the Battle of Malvern Hill. By Sneden. |

Early on the morning of the battle, Lee met with his lieutenants, including

Maj. Gens. James Longstreet, A. P. Hill, Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson, John Magruder and D. H. Hill. Hill, after talking with

a chaplain familiar with the geography of Malvern Hill, cautioned against mounting an attack. "If General McClellan is there

in strength," Hill said, "we had better let him alone." Longstreet laughed off Hill's objections, saying "Don't get so scared,

now that we've got him [McClellan] whipped."

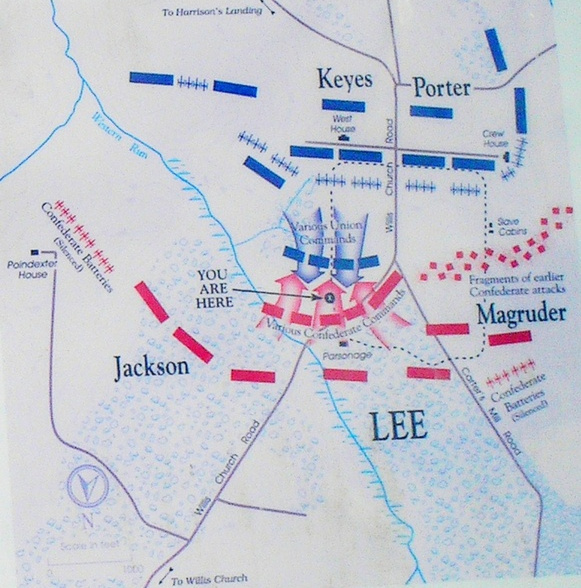

Lee chose the relatively well-rested commands of D. H. Hill, "Stonewall"

Jackson and John Magruder to lead the Confederate offensive, as they had barely participated in the fighting of the day before.

Meanwhile, James Longstreet's First Corps and A. P. Hill's Light Division, who had fought the majority of the previous day's

hostilities, would be held in reserve. According to Lee's plan, the Army of Northern Virginia would form a semi-circle enveloping

Malvern Hill. D. H. Hill's five brigades would be placed along the northern face of the hill, forming the center of the Confederate

line, and the commands of "Stonewall" Jackson and John Magruder would take the left and right flanks, respectively. Whiting's

forces would position themselves on the Poindexter farm, with the outfits of Brig. Gen. Charles Sidney Winder and Richard

Ewell nearby. The infantry of these three detachments would provide reinforcement for the Confederate line if necessary. Maj.

Gen. Theophilus Holmes would take up a position on the extreme Confederate right flank.

The Army of the Potomac's disposition in the lead-up to the battle was more

orderly than Lee's Army of Northern Virginia; all of McClellan's forces would be concentrated in one place, save for several

divisions from Maj. Gen. Erasmus Keyes's outfit and Keyes himself, who were posted across the James River at Haxall's Landing.

A Confederate scout observed Union soldiers resting in position, and moving about the hill unworried, whilst the disposition

of the cannons around the hill's slope gave him the impression that the position was "almost impregnable". McClellan's army

was indeed on the hill in force.

Throughout the Seven Days Battles, Lee's forces had been separated and scattered

due to swamps, narrow roads and other geographic obstacles, and occasionally due to unclear orders. As the days of marching

and fighting wore on the number of stragglers swelled to fill narrow roads and significantly deplete the Confederate ranks,

presenting a significant additional strain on their combat readiness. These hindrances continued during the Battle of Malvern

Hill, with both Magruder and Huger making mistakes in the deployment of their forces.

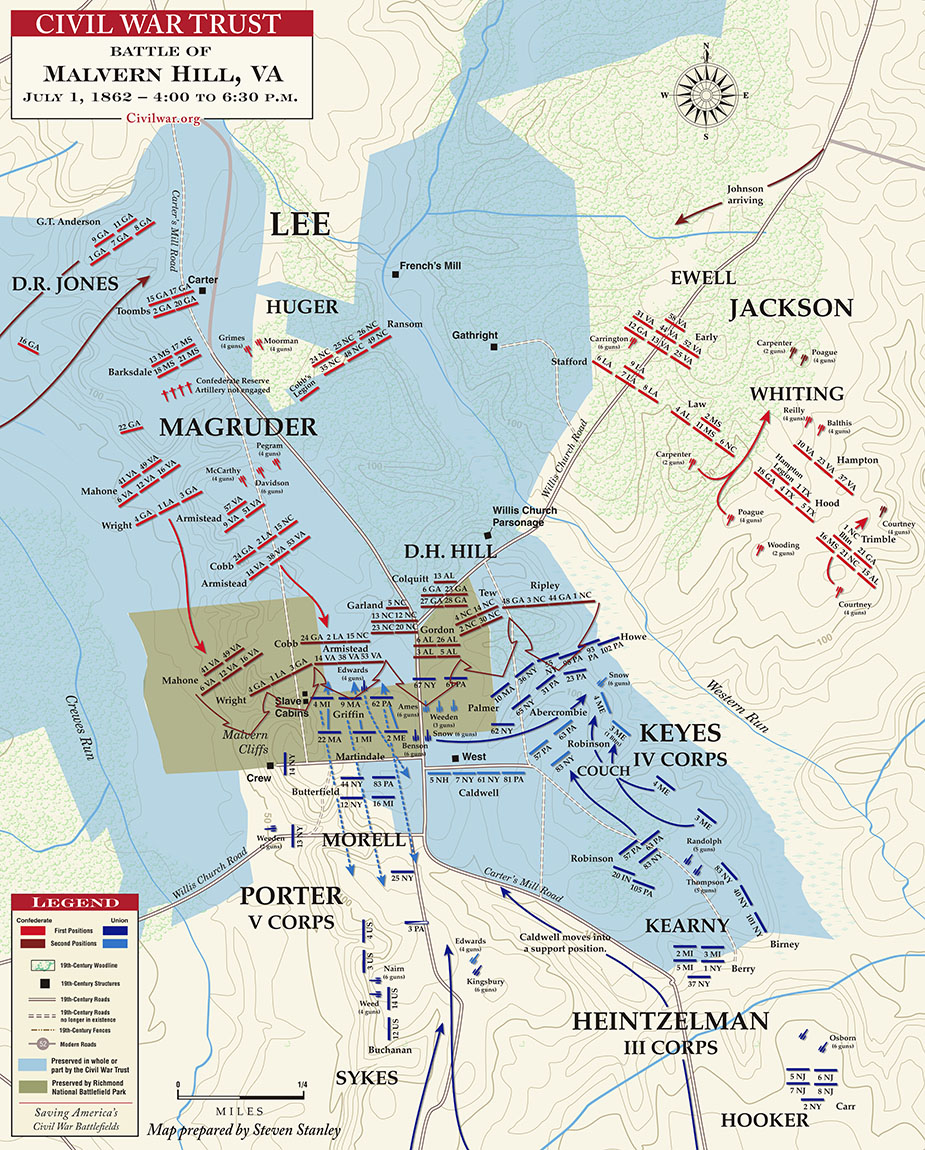

| Battle of Malvern Hill Battlefield Map |

|

| Civil War Malvern Hill Map |

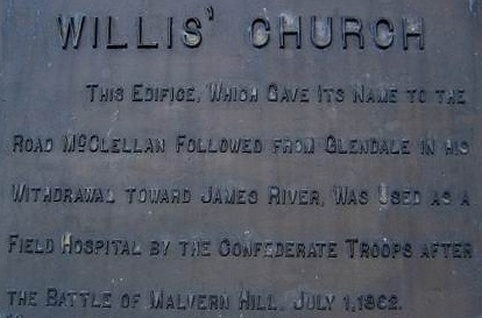

At first, Magruder's units were behind "Stonewall" Jackson's

column while marching down the Long Bridge Road, which led to Malvern Hill. Along this road were several adjoining pathways.

One such road, called the Willis Church Road by some locals and the Quaker Road by others, led south from Glendale to Malvern

Hill. Lee's maps labeled this "Quaker Road". Another of these paths began near a local farm and angled southwest toward an

upriver point on the River Road—some locals called this the Quaker Road, including Magruder's guides, who led Magruder's

army down this road rather than the Quaker Road shown on Lee's maps. James Longstreet eventually rode after Magruder, and

persuaded him to reverse course. This incident delayed Magruder's arrival to the battlefield for three hours.

Huger, worried about clashing with Union forces while marching towards Malvern

Hill, had also failed to manage his division effectively. He deployed two of his brigades, commanded by Brig. Gens. Lewis

Armistead and Ambrose Wright, to perform a flanking maneuver around any Federals they found, to avoid the Union threat. Longstreet

eventually notified Huger that he would be unobstructed by Federal forces if he marched to Malvern Hill. Huger, however, remained

in place until someone from Lee's headquarters came to guide them to the battlefield. As

noon drew near with no sight of either Huger or Magruder, who were supposed to be manning the Confederate right flank, Lee

replaced these two forces with the smaller units of Brig. Gens. Armistead and Wright, two of Huger's brigades that had reached

the battlefield some time earlier. Huger and his other two brigades (under Brig. Gens. Ransom and Mahone) were still too far

north of the scene. Despite the mishaps and disunity, Malvern Hill would be the first time during the Seven Days Battles that

Lee managed to concentrate his force.

| Malvern Hill, Virginia |

|

| Malvern Hill |

Battle: Malvern Hill is more suitable for defense than

most spots in central Virginia. In 1862 the nearest body of Confederate-held trees stood approximately 800 yards from the

crest of the hill, and in most directions the distance was closer to a full mile. When Lee’s men finally attacked

late in the afternoon, most of them spent a deadly ten or fifteen minutes ascending gently rising, open ground. Union

artillerists rejoiced at their opportunity and delivered cannon fire of unprecedented violence on the Confederate infantry.

Lee initially surveyed

the left flank himself for possible artillery positions. After a reconnoitering expedition on the right flank, James Longstreet returned

to Lee and the two compared their results and concluded that two grand battery-like positions would be established at the

left and right sides of Malvern Hill. The converging artillery fire from the batteries, they reasoned, could weaken the Union

line so that a Confederate infantry attack could break through. If this plan did not work out, Lee and Longstreet felt the

artillery fire would buy them time to consider other plans.

With a battle plan in order, Lee sent a draft to his lieutenants, written

by his chief of staff, Col. Robert Chilton. The orders were not well-crafted, however, since they designated the yell of a

single charging brigade as the only signal of attack for a full fifteen brigades. Amid the tumult and clamor of battle, this

was bound to create confusion. Moreover, Chilton's draft effectively left the attack solely at the discretion of Lewis Armistead,

who had never before held command of a brigade during battle. The draft also did not note the time that it had been written,

which later caused confusion for Magruder.

Beginning around 1 pm, Union artillery fired first, initially upon infantry

in the woods, and later upon any Confederate artillery that attempted to move into firing position. On the Confederate left

flank, two batteries from Whiting's division and one from Jackson's soon began firing from their position upon Darius Couch's

division of the IV Corps, who were near the center of the Union line. This began a fierce firefight, with the Union's eight

batteries and 37 guns concentrated against three Confederate batteries and sixteen guns. The Union fire silenced the Rowan

Artillery and made their position untenable. The other two Confederate batteries, placed by Jackson himself, were in somewhat

better positions, and managed to keep firing. Over a period of more than three hours, a total of six or eight Confederate

batteries engaged the Union Army from the Confederate left flank, but they were usually engaged only one at a time.

On the Confederate right flank a total of six batteries engaged the Federals,

but they did so one-by-one instead of in unison, and each was consecutively cut to pieces by concentrated Union artillery

fire. Moreover, they engaged the Union artillery later than the guns of the left flank, so the desired crossfire bombardment

was never achieved.

| Malvern Hill Battlefield |

|

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

| Battle of Malvern Hill and Seven Days Battles Map |

|

| Seven Days Battles of the Peninsula Campaign |

Altogether, the Confederate artillery barrage on both flanks completely

failed to achieve its objectives. Confederate fire did manage to kill Capt. John E. Beam of the Union's 1st New Jersey Artillery,

along with a few others, and several Federal batteries (though none that were actually engaged) had to move to avoid the fire.

Although the barrage by Lee's forces did claim a few lives, Union forces remained unfazed and continued their fearsome barrage.

Indeed, Union Army Lt. Charles B. Haydon supposedly fell asleep during the artillery fight. On both the left and right flanks,

several of the batteries that did engage lasted no more than minutes before being rendered incapable of fire. Moreover, in

a failure of command that, according to historian Thomas M. Settles, must ultimately be placed on Lee's shoulders, the movements

of the two flanks were never coordinated with one another. D. H. Hill found the failure of the Confederate artillery discouraging

and later dismissed the barrage as "most farcical".

Meanwhile, the Union artillery fire was planned and directed nearly flawlessly.

Col. Hunt, McClellan's chief of artillery, continuously refocused Union fire on various fronts, in an "enormous sheaf of fire

of more than 50 superior pieces, disabling four of Huger's and several of Jackson's batteries almost the instant they came

into action".This severely hampered the Confederates' ability to respond effectively to the Federal barrage. The Union artillery

subdued a number of the Southerners' batteries; those few that remained attacked piecemeal, and failed to produce any significant

result.

Intense Confederate and especially Union artillery fire continued for at

least an hour, slackening at about 2:30 pm. At about 3:30 pm, Lewis Armistead noticed Union skirmishers creeping towards his

men where the grand battery on the Confederate right flank was, nearly within rifle range of them. Armistead sent three regiments

(about half of his brigade) from his command to push back the skirmishers, thus beginning the infantry part of the battle.

The skirmishers were repelled quickly, but Armistead's men found themselves in the midst of an intense Union barrage. The

Confederates decided to nestle themselves in a ravine along the hill's slant. This position protected them from the fire,

but pinned them down on the slopes of Malvern Hill, unsupported by either infantry or artillery. They did not have enough

men to advance any further and retreating would have put them back into the crossfire.

Not long after the advance of Armistead's regiments, John Magruder

and his men arrived near the battlefield, albeit quite late because of the confusion regarding the names of local roads—by

this time, it was 4 pm. Magruder was told at that morning's war council to move to Huger's right, but he was unaware of Huger's

position, and sent Major Joseph L. Brent to locate Huger's right flank. Brent found Huger, who said that he had no idea where

his brigades were. Huger was noticeably upset that his men had been given orders by someone other than himself; Lee had told

Huger's two brigades under Armistead and Ambrose Wright to advance to the right part of the Confederate line. Upon hearing

of this, Magruder was quite confused. He sent Capt. A. G. Dickinson to find Lee and inform him of the "successful" charge

of Armistead's men and request further orders. Contrary to this message, Armistead was in fact pinned down halfway up Malvern

Hill. At the same time, Whiting sent Lee an incorrect report that Union forces were retreating. Whiting had mistaken two events

for a Federal withdrawal—the movement of Edwin Sumner's troops, who were adjusting their position to avoid the Confederate

fire, and the relaxing of Union fire on his side, which was actually the Union artillery concentrating their firepower to

a different front. Whiting and Magruder's erroneous reports led Lee to send a draft of orders to Magruder via Dickinson: "General

Lee expects you to advance rapidly", wrote Dickinson. "He says it is reported that the enemy is [retreating]. Press forward

your whole line and follow up Armistead's success." Before Dickinson returned with these orders, Magruder was belatedly handed

the order sent out three hours previously (at 1:30 pm) by Chilton. Since no time was affixed to the text of the orders, Magruder

was unaware that these orders had been rendered meaningless by the failure of the Confederate artillery during the past few

hours, and believed he had received two successive orders from Lee to attack.

| Malvern Hill Civil War Battlefield |

|

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

| Magruder and Hill at Malvern Hill |

|

| Malvern Hill Battlefield |

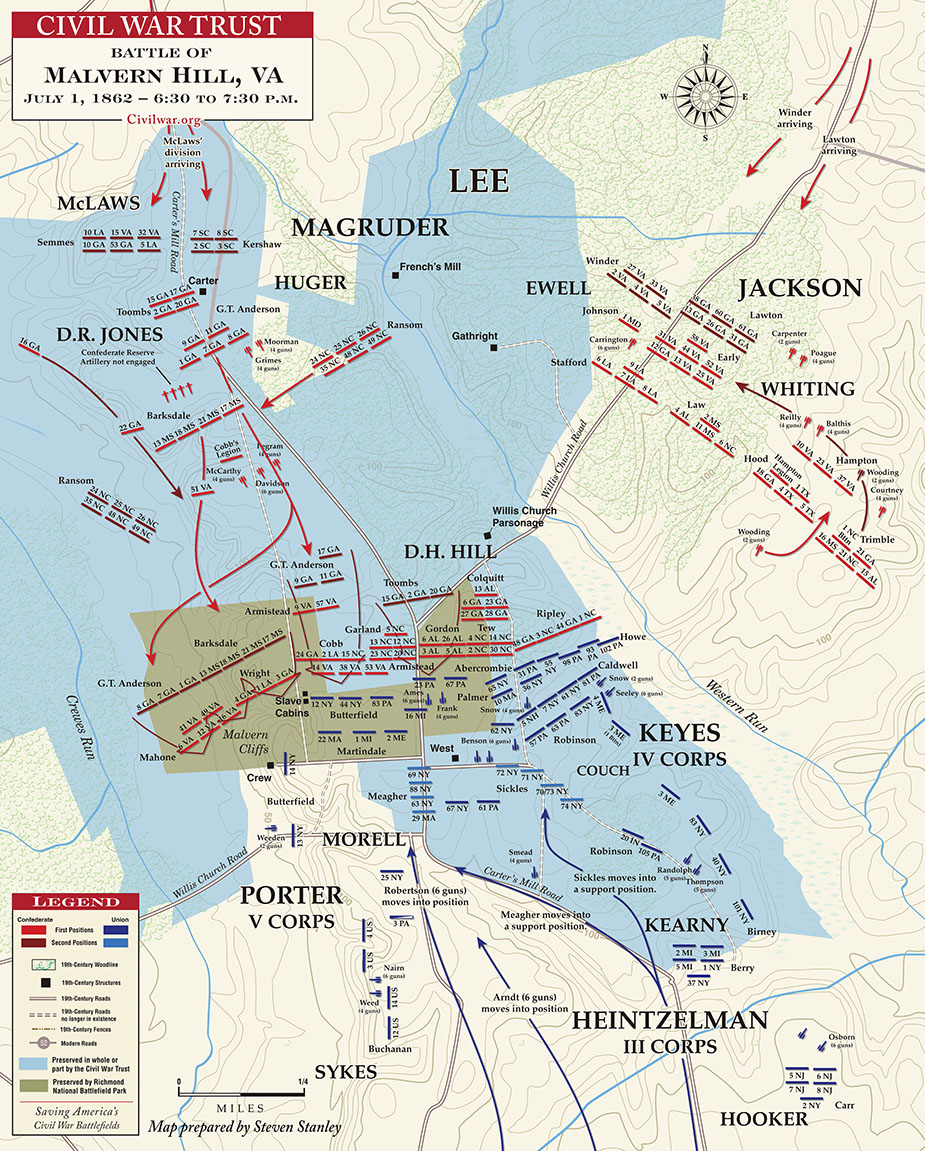

Believing himself bound by Lee's order to charge, but with his own brigades

not yet in attacking position, Magruder mustered some five thousand men from Huger's brigades, including those of Ambrose

Wright and Maj. Gen. William Mahone and half of the men from Armistead's brigade who were caught in the open battlefield.

Magruder had also sent for Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom, Jr., also under Huger's command, who noted that he had been given strict

instructions to ignore any orders not originating from Huger, and apologetically said he could not help Magruder. Magruder

additionally ordered men under his personal command—three regiments of Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb's brigade, plus Col. William

Barksdale's full brigade—to the attack. Because of the confusion regarding Quaker Road, however, these brigades were

not yet near enough to do more than move into supporting position, and Magruder wanted to attack immediately. Despite this,

under Magruder's order at about 5:30 pm, Wright's brigade with Armistead's, then Mahone's brigade, started darting out of

the woods and towards the Union line. The artillery of the Confederate left flank, under Jackson's personal command, also

renewed their barrage with the late arrival of two batteries of Richard Ewell's division. The Confederates were initially

engaged solely by Union sharpshooters, but the latter quickly fell back to give their own artillery a clear field of fire.

Federal cannoneers employed canister shot with deadly effect. Wright's men were pinned down in a small depression on

the rolling hillside, to the right of Armistead's; Mahone's were driven back into retreat in about the same area. At some

point during the first wave of assaults, Cobb moved into close supporting position behind Armistead. Barksdale's men were

also supporting, to the left of Armistead.

The firefight also alerted the three Union boats on the James—the ironclad

USS Galena, and the gunboats USS Jacob Bell and USS Aroostook—which began lobbing missiles

twenty inches in length and eight inches (200 mm) in diameter from their position on the James River onto the battlefield.

The explosions and impacts of the gunboat fire impressed the Confederate troops, but the guns' aim was unreliable, and the

large shells did considerably less damage than might have been expected.

D. H. Hill had been discouraged by the failure of the Confederate artillery,

and asked "Stonewall" Jackson to supplement Chilton's draft. Jackson's response was that Hill should obey the original orders:

charge with a yell after Armistead's brigade. No yell was heard for hours, and Hill's men began building bivouac shelters

to sleep in. Around 6 pm, Hill and his five brigade commanders had assumed that the lack of a signal meant that their army

would not attempt any assault. They were conferring together about Chilton's order when they heard yells and the commotion

of a charge from their right flank, roughly where Armistead was supposed to be Hill took the yell as the signal and shouted

to his commanders, "That must be the general advance. Bring up your brigades as soon as possible and join in it." D. H. Hill's

five brigades, with some 8,200 men, had to contend with the dense woodlands around the Quaker Road and Western Run, which

destroyed any order they may have had. Men advanced out of the woods towards the Union line in five separate, uncoordinated

attacks, and each brigade charged up the hill alone: "We crossed one fence, went through another piece of woods, then over

another fence [and] into an open field on the other side of which was a long line of Yankees", wrote William Calder of the

2nd Regiment, North Carolina Infantry. "Our men charged gallantly at them. The enemy mowed us down by fifties." Some brigades

in Hill's division made it close enough to exchange musket fire and engage in hand-to-hand combat, but these were driven back.

The artillery response on the Federal side to Hill's charge was particularly withering, and soon, Hill's men needed support

just to hold their ground. In Extraordinary Circumstances: The Seven Days Battles, Brian K. Burton called Hill's charge "unnecessary

and costly." The successive assaults of Hill's brigades on the well-entrenched Federals were short-lived, and achieved little.

| Malvern Hill Civil War Map |

|

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

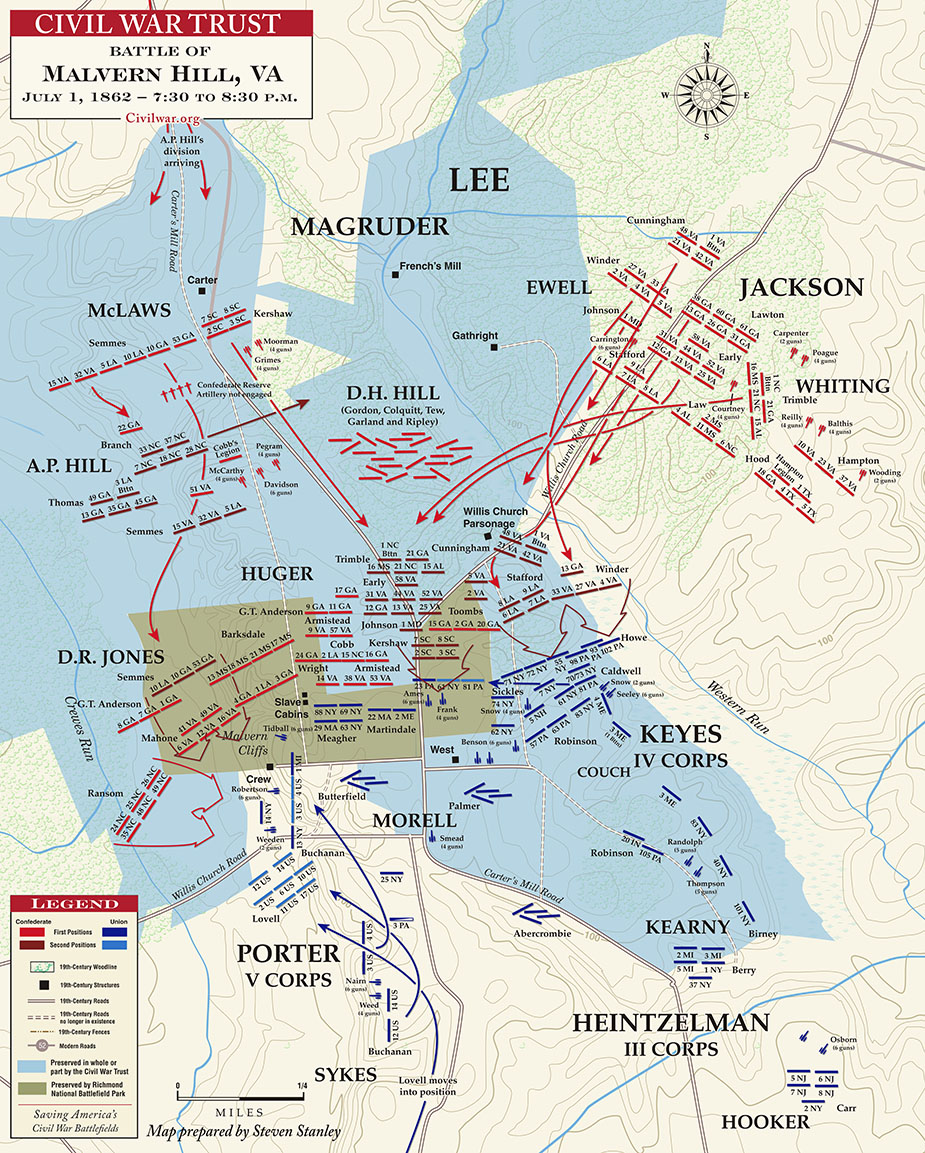

Preceding attacks by Lee's army had done barely anything to accomplish Confederate

objectives, but this did not deter Magruder, who rode back and forth across the battlefield, calling for reinforcements and

personally launching unit after unit into a charge of the Union line. At this point, men who had always been directly under

Magruder's command began to join the battle. Magruder first encountered some units of Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs. With Toombs's

brigade widely dispersed, the individual units Magruder found were not with Toombs himself. Magruder personally led the men

in a short-lived charge, followed by a disordered retreat. Other units nominally under Toombs's command appeared, charged

and retreated at various times throughout the next few hours, with little or no organization. The brigades of Col. George

T. Anderson and Col. William Barksdale emerged from the woods to the right of Toombs, but as they did so, Anderson's men also

became separated, as the left side outpaced the right. This created an advance with two of Anderson's regiments on the far

Confederate left next to Toombs, Barksdale's men in the middle, and three more Anderson regiments on the far right, near the

remnants of Wright and Mahone. Anderson's right flank charged, but made it no farther than the foot of the hill before breaking

and retreating under a hail of canister shot. Anderson's left flank never charged. Barksdale's brigade charged at roughly

the same time, and made it considerably farther up the hill, engaging the Union infantry of Brig. Gen. Daniel Butterfield

in a firefight that lasted more than an hour.

Lee received Magruder's calls for reinforcement and instructed Huger to let

Ransom go support the men trapped on the field of battle. He also sent orders to the brigades of Brig. Gens. Joseph B. Kershaw

and Paul Jones Semmes, in Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws's division within Magruder's command. Robert Ransom's unit, after they

finally showed up with Huger's permission, first attempted to charge straight up the hill, following the path of other Confederate

brigades attempting to aid Magruder. When this proved useless, Ransom ordered them to regroup in the woods to the Confederate

right, march double-time a half a mile in a hook to the right around all the other Confederate units and attack the far Union

western flank. While Ransom was angling west, Jackson responded to a request for reinforcement from D. H. Hill by sending

forward brigades from his own command to move from the east into the area where D. H. Hill had attacked. From his own division

Jackson sent Brig. Gens. Alexander Lawton and Charles S. Winder, and from Ewell's division, Brig. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble and

Cols. Leroy A. Stafford and Jubal Early.

Ransom's men managed to come closer to the Union line than any Confederates

that day, guided by the flashing light of the cannons amidst an encroaching darkness; however, George Sykes's artillery repelled

that attack. The brigades of Kershaw and Semmes, sent earlier by Lee, arrived to the front while Ransom was moving to attack

in another position. Semmes and Kershaw were quickly sent in; they too were repulsed not long after. Semmes was west of the

junction of Carter's Mill Road and Willis Church Road, in the vicinity of Barksdale, Mahone and Wright. Semmes made the final

charge of the day west of these roads, and like the charges before, it was to little effect. Kershaw angled east, in the area

where Toombs, Anderson and Cobb had attacked. This was an area of great confusion. Kershaw's troops arrived ahead of all the

reinforcements sent by Jackson, and took fire from both friendly and hostile forces: from Confederates behind them firing

wildly and Federals in front firing effectively. Kershaw's men retreated in rout. The brigades behind Kershaw charged incoherently,

with some men pushing forward, and others getting separated from their units or confused when they encountered groups of retreating

Confederates. Disorganized, retreating soldiers from various units were so numerous that they slowed Jackson's men to nearly

a standstill. Jackson's unit commanders attempted to organize their various regiments and rally the retreaters to join in,

but it was all to very little effect. A few units fought fiercely against Union infantry and artillery. In particular, three

regiments of Barlow's brigade made it close enough to Union lines to engage in hand-to-hand combat with the troops of Brig.

Gen. Daniel Sickles before being driven back. Night was falling, however,

and eventually all of these troops were ordered to merely hold their positions without charging. In the end, the charges of

Semmes and Kershaw were the last coherent Confederate actions, and neither was successful. Brig. Gen. Porter summed up the

Confederate infantry charges at Malvern Hill this way:

"As if moved by a reckless disregard of life equal to that displayed at Gaines'

Mill, with a determination to capture our army, or destroy it by driving us into the river, brigade after brigade rushed at

our batteries, but the artillery of both Morell and Couch mowed them down with shrapnel, grape, and canister, while our infantry,

withholding their fire until the enemy were in short range, scattered the remnants of their columns, sometimes following them

up and capturing prisoners and colors."

| Malvern Hill Battlefield Map |

|

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

With the infantry now removed from the battle, Union artillery continued

to boom and scream across the hill. The Confederates made several daring yet suicidal assaults headlong into Federal

artillery, resulting in an ominous bloodbath. The field, said one Union officer, looked as though a sickle had swept it, removing

everything that had once stood. When firing ceased at 8:30 pm, a wreath of smoke hovered upon the crest's edge,

as thousands of men in both blue and gray lay dead and dying on the fields of Malvern

Hill.

This final battle of the Seven Days was the first in which the Union Army had occupied very good ground. For

the preceding six days, McClellan's Army of the Potomac had been retreating to the safety of the James River, pursued by Lee's

Army of Northern Virginia. Heretofore, the major battles of the Seven Days had been mostly inconclusive, but McClellan was

unnerved by Lee's aggressive assaults and remained convinced that he was seriously outnumbered, although in fact the two armies

were roughly equal in size. "More

than five thousand dead and wounded men were on the ground," a Union officer reported next dawn, ”but enough were

alive and moving to give the field a singular crawling effect.” Gen.

Lee's army had suffered a staggering 5,355 casualties compared to Union losses of 3,214 in this epic contest, but Lee

continued to press the Union army all the way to Harrison's Landing. Malvern Hill also ended the Peninsula Campaign. When

McClellan's army ceased to threaten Richmond, Lee sent "Stonewall" Jackson to operate against Maj. Gen. John Pope's army along

the Rapidan River, thus initiating the Northern Virginia Campaign. See also Battle of

Malvern Hill.

Casualties: The human toll of the Battle of Malvern

Hill and the Seven Days Battles was shown clearly as both capitols, Washington and Richmond, which established numerous provisional

hospitals to care for the wounded. Ships sailed from the Peninsula to Washington carrying the wounded. Richmond was nearest

to the battlefields of the Seven Days, and the immense number of casualties meant that graves could not be dug quickly enough.

The wounded were arriving by the hundreds and therefore overwhelmed the hospitals and doctors. Although volunteers descended

upon Richmond to care for the conflict's casualties, surgeons were few and far between.

Union losses were more than 3,000, but Confederates casualties were high because of command decisions to advance

the men time and again directly into heavy Federal artillery fire. As the cannonading raked the Rebel ranks with shot

and shell, it was obvious, soon to both sides, that the men were being pressed like fodder. Daniel

Harvey Hill, one of only two lieutenant generals from North Carolina, is often quoted with this slaughter by saying it was

not war, but murder. On the morning of the fight, Hill, pointing to the sloped terrain of the hill, made prophetic

like comments to Longstreet, saying that if the Federals are there in strength, then we better leave them alone.

Longstreet merely laughed. Confederate casualties would number more than 5,000

by nightfall.

Some 30,000 Confederates engaged that day, though several thousand more endured

the Union shelling. Whiting's unit suffered 175 casualties at Malvern Hill, even though they had limited involvement in the

assaults. Charles Winder's brigade of just over 1,000 men suffered 104 casualties in their short involvement in the battle.

D. H. Hill spent days removing the wounded, burying the dead and cleaning up the battlefield, with help from Magruder and

Huger's units. One of D. H. Hill's brigades lost 41 percent of its strength at Malvern Hill alone—men that could scarcely

be replaced. He later estimated that more than half of all the Confederate killed and wounded at Malvern Hill were as a result

of artillery fire.

| Battle of Malvern Hill |

|

| Battle of Malvern Hill and Seven Days Battles |

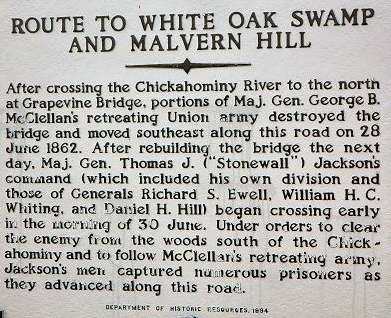

| On the Road to Malvern Hill |

|

| Malvern Hill Civil War History |

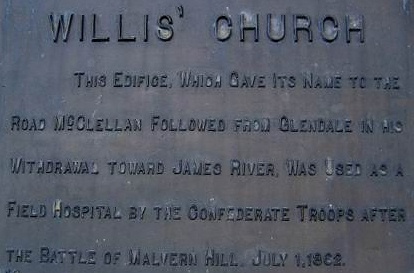

| Willis Church & Malvern Hill |

|

| Civil War Battle of Malvern Hill |

Analysis: The

Battle of Malvern Hill, also known as the Battle of Poindexter's Farm, was fought on July 1, 1862, between the Confederate

Army of Northern Virginia, led by Gen. Robert E. Lee, and the Union Army of the Potomac under Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan.

It was the final battle of the Seven Days Battles during the American Civil War, taking place on a 130-foot elevation of land

known as Malvern Hill, near the Confederate capitol of Richmond, Virginia and just one mile from the James River. Large bodies

of infantry took part, using more than two hundred pieces of artillery and three warships.

The Seven Days Battles was the pinnacle of the Peninsula Campaign, during

which McClellan's Army of the Potomac sailed around the Confederate lines, landed at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula, southeast

of Richmond, and struck inland towards the Confederate capitol. Confederate commander-in-chief Joseph E. Johnston fended off

McClellan's repeated attempts to take the city, slowing Union progress on the peninsula to a crawl. When Johnston was wounded,

Lee assumed command and launched a series of counterattacks, collectively called the Seven Days Battles. These attacks

culminated in the action on Malvern Hill.

The Union's V Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter, took up positions

on the hill on June 30. McClellan was not present for the initial exchanges of the battle, having boarded the ironclad USS

Galena and sailed down the James River to inspect Harrison's Landing, where he intended to locate the base for his

army. Confederate preparations were hindered by several mishaps. Bad maps and poor guides caused Confederate Maj. Gen. John

Magruder to be late for the battle, an excess of caution delayed Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger, and Maj. Gen. "Stonewall" Jackson

had problems collecting the Confederate artillery.

The battle occurred in stages: an initial exchange of artillery fire, a minor

charge by Confederate Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead, and three successive waves of Confederate infantry charges triggered by

unclear orders from Lee and the actions of Maj. Gens. Magruder and D. H. Hill, respectively. In each phase, the effectiveness

of the Federal artillery was the deciding factor, repulsing attack after attack, resulting in a tactical Union victory. After

the battle, McClellan and his forces withdrew from Malvern Hill to Harrison's Landing, where he remained until August 16.

His plan to capture Richmond had been thwarted.

In the course of four hours, a series of blunders in planning and communication

had caused Lee's forces to launch three failed frontal infantry assaults across hundreds of yards of open ground, unsupported

by Confederate artillery, charging toward firmly entrenched Union infantry and artillery defenses. These errors provided Union

forces with an opportunity to inflict heavy casualties. In the aftermath of the battle, however, the Confederate press heralded

Lee as the savior of Richmond. In stark contrast, McClellan was accused of being absent from the battlefield, a harsh criticism

that haunted him when he ran for president in 1864.

The final battle of the Seven Days was the first in which the Union Army occupied

favorable ground. Malvern Hill offered good observation and artillery positions, having been prepared the previous day by

Porter's V Corps. McClellan himself was not present on the battlefield, having preceded his army to Harrison's Landing on

the James, and Porter was the most senior of the corps commanders. The slopes were cleared of timber, providing great visibility,

and the open fields to the north could be swept by deadly fire from the 250 guns placed by Col. Henry J. Hunt, McClellan's

chief of artillery. Beyond this space, the terrain was swampy and thickly wooded. Almost the entire Army of the Potomac occupied

the hill and the line extended in a vast semicircle from Harrison's Landing on the extreme right to Brig. Gen. George W. Morell's

division of Porter's corps on the extreme left, which occupied the geographically advantageous ground on the northwestern

slopes of the hill.

| Battle of Malvern Hill and Seven Days Battles |

|

| Battle of Malvern Hill and Seven Days Battles |

Rather than flanking the position, Lee attacked it directly, hoping that his

artillery would clear the way for a successful infantry assault. His plan was to attack the hill from the north on the Quaker

Road, using the divisions of "Stonewall" Jackson, Richard S. Ewell, D. H . Hill, and Brig. Gen. William H. C. Whiting. Magruder

was ordered to follow Jackson and deploy to his right when he reached the battlefield. Huger's division was to follow as well,

but Lee reserved the right to position him based on developments. The divisions of Longstreet and A. P. Hill, which had been

the most heavily engaged in Glendale the previous day, were held in reserve.

Once again, Lee's complex plan was poorly executed. The approaching soldiers

were delayed by severely muddy roads and poor maps. Jackson arrived at the swampy creek called Western Run and stopped abruptly.

Magruder's guides mistakenly sent him on the Long Bridge Road to the southwest, away from the battlefield. Eventually the

battle line was assembled with Huger's division, the brigades of Brig. Gens. Ambrose R. Wright and Lewis A. Armistead, on

the Confederate right and D. H. Hill's division (brigades of Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood and Col. Evander M. Law) on the Quaker

Road to the left. They awaited the Confederate bombardment before attacking.

Unfortunately for Lee, Henry Hunt struck first, launching one of the greatest

artillery barrages in the war from 1 p.m. to 2:30 p.m. The Union gunners had superior equipment and expertise and disabled

most of the Confederate batteries. Despite the setback, Lee sent his infantry forward at 3:30 p.m. and Armistead's brigade

made some progress through lines of Union sharpshooters. By 4 p.m., Magruder arrived and he was ordered forward to support

Armistead. His attack was piecemeal and poorly organized. Meanwhile, D. H. Hill launched his division forward along the Quaker

Road, past Willis Church. Across the entire line of battle, the Confederate troops reached only within 200 yards of the Union

Center and were repulsed by nightfall with heavy losses.

In this single-day's battle, Lee's army suffered 5,355 casualties while Union

losses were 3,214 in this disastrous fight. Lee, nevertheless, continued to press the Federals all the way to Harrison's

Landing. On Evelington Heights, part of the property of Edmund Ruffin, the Confederates had an opportunity to dominate the

Union camps, making their position on the bank of the James potentially untenable. Although the Confederate position would

be subjected to Union naval gunfire, the heights were an exceptionally strong defensive position that would have been very

difficult for the Union to capture with infantry. Cavalry commander Jeb Stuart reached the heights and began bombardment with

a single cannon. This alerted the Federals to the potential danger and they captured the heights before any Confederate infantry

could reach the scene.

For the remainder of the war, Lee would repeat these suicidal frontal assaults by ordering his soldiers directly

into strong artillery positions, with Pickett's Charge, the following summer, being one of the more notorious ones. Lee,

as many say, was an excellent general, but to continually push and press and churn his armies into cannon fodder was

indeed reckless. Unwarranted, too, because we are talking about a charge, not a countercharge or a breakout attempt,

and Lee had other offensive options to choose from on the table.

| Stonewall Jackson Advances |

|

| Stonewall and Malvern Hill |

| Willis Church & Malvern Hill |

|

| Willis Church and Battle of Malvern Hill |

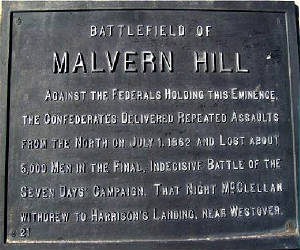

| Civil War Battle of Malvern Hill, Virginia |

|

| Battle of Malvern Hill, Virginia |

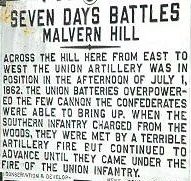

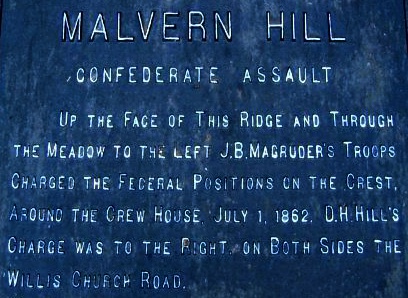

(Left) Battle of Malvern Hill Historical Marker: Against the Federals

holding this eminence, the Confederates delivered repeated assaults from the North on July 1, 1862, and lost about 5,000 men

in the final, indecisive Battle of the Seven Days Campaign. That night McClellan withdrew to Harrison's Landing, near Westover.

Seven Days Battles and

Malvern Hill: The second phase of the Peninsula Campaign consisted of six major battles and several skirmishes,

including the Battle of Malvern Hill, which took a negative turn for the Union when Lee assumed command and launched

fierce counterattacks just east of Richmond. Known as the Seven Days Battles (June 25–July 1, 1862),

the battles and skirmishes are formally considered part of the Peninsula Campaign, with an aggressive Lee in command and on

the offensive against a determined but retreating McClellan. See also Seven Days Battles Around Richmond.

The Seven Days began on June 25, 1862, when the Federals pressed the action during the Battle of Oak Grove, but McClellan

quickly lost the initiative as Lee began a series of assaults at Beaver Dam Creek (Mechanicsville) on June 26, Gaines' Mill

on June 27, the actions at Garnett's and Golding's Farm on June 27–28, and the attack on the Union rear guard at

Savage's Station on June 29. McClellan's Army of the Potomac continued its retreat toward the safety of Harrison's Landing

on the James River

Lee's final opportunity to intercept

the Union Army was at the Battle of Glendale on June 30, but poorly executed orders allowed his enemy to escape to a strong

defensive position on Malvern Hill. At the Battle of Malvern Hill on July

1, Lee launched suicidal frontal assaults and suffered heavy and unnecessary casualties in the face of strong infantry and

well positioned artillery defenses. Although the Union infantry was well entrenched, it was supported by an impenetrable

wall of 250 field pieces. The formidable array of 250 cannons enjoyed an added presence of three Union gunboats

on the James River, the USS Galena, USS Jacob Bell, and USS Aroostook.

Gen. Lee's assaults were

impractical and unnecessary for several reasons, but he was determined to halt and destroy the Army of the Potomac by

advancing waves of infantry, with negligible artillery support, directly into massed artillery, that resulted in more

than 5,000 Confederate casualties without gaining an inch of ground. Lee's ill-fated and poorly coordinated plan

had also been complicated with faulty maps and muddy roads. Perhaps the Confederate general's prior successes outweighed prudence. For

the Federals, this fight was won before it began. The Union artillery, for example, had silenced practically every Confederate

battery within ninety minutes. Although without adequate artillery support, the Rebels, nevertheless, were still ordered by

Lee to advance across open fields and into the Union lines, a fate that would also plague Lee, with more devastating losses,

during Pickett's Charge. Malvern Hill was considered one of the most unnecessary yet disastrous attacks of the entire war.

Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill wrote in a postwar article that Malvern Hill wasn't war; it was murder. The Seven Days ended with McClellan's army in relative safety next to the James

River, having suffered almost 16,000 casualties during the retreat. Lee's army, which had been on the offensive

during the Seven Days, lost over 20,000. As Lee became convinced that McClellan would not resume his threat against Richmond, he moved north for the Northern Virginia Campaign and the

Maryland Campaign.

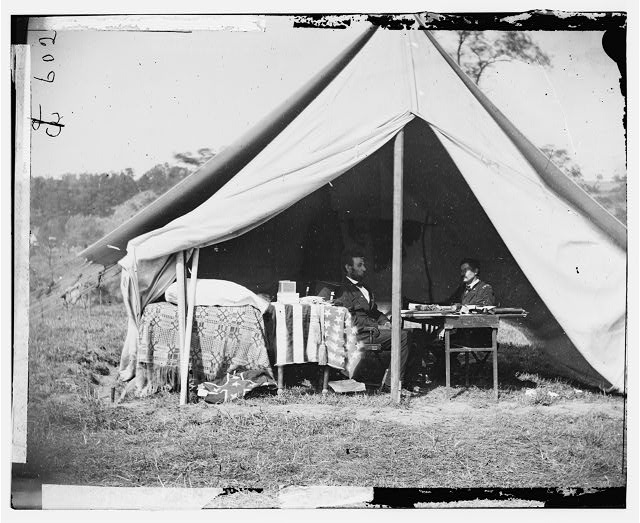

| President Lincoln and McClellan in 1862 |

|

| President Lincoln and George McClellan in 1862 |

Peninsula Campaign: Both sides claimed victory,

when McClellan and Johnston initially opposed each other during the Peninsula Campaign, but neither side's accomplishment

was impressive. George B. McClellan's advance on Richmond was halted and the Army of Northern Virginia fell back into the Richmond defensive works. Despite claiming victory, McClellan was shaken by the experience. He wrote to his wife, "I am tired of the sickening

sight of the battlefield, with its mangled corpses & poor suffering wounded! Victory has no charms for me when purchased

at such cost." McClellan redeployed all of his army

except for the V Corps south of the river, and although he continued to plan for a siege and the capture of Richmond, he lost

the strategic initiative. An offensive begun by the new Confederate commander, Gen. Robert E. Lee, would be planned while

the Union troops passively sat in the outskirts of Richmond.

The Seven Days Battles drove the Union Army back to the James River

and saved the Confederate capitol. The change in leadership of the Confederate Army in the field, from Joe Johnston

to Robert E. Lee, as a result of Seven Pines had a profound effect on the war. On June 24, 1862, McClellan's massive Army

of the Potomac was within 6 miles of the Confederate capitol of Richmond;

Union soldiers wrote that they could hear church bells ringing in the city. Within 90 days, however, McClellan had been driven

from the Peninsula, Pope had been soundly beaten at the Second Battle of Bull Run, and battle lines were 20 miles from the

Union capitol in Washington. It would take almost two more

years before the Union Army again got that close to Richmond,

and almost three years before it captured it.

McClellan, Peninsula Campaign, Civil War, and

Lincoln: McClellan's Peninsula Campaign in 1862 ended in failure, with retreats from attacks by General

Robert E. Lee's smaller army and an unfulfilled plan to seize the Confederate capitol of Richmond.

His performance at the bloody Battle of Antietam blunted Lee's invasion of Maryland,

but allowed Lee to eke out a precarious tactical draw and avoid destruction, despite being outnumbered. As a result, McClellan's

leadership skills during battles were questioned by President Abraham Lincoln, who eventually removed him from command, first

as general-in-chief, then from the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln

was famously quoted as saying, "If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it for a time!"

General

McClellan also failed to maintain the trust of Lincoln, and

proved to be frustratingly derisive of, and insubordinate to, his commander-in-chief. After he was relieved of command, McClellan

became the unsuccessful Democratic nominee opposing Lincoln

in the 1864 presidential election.

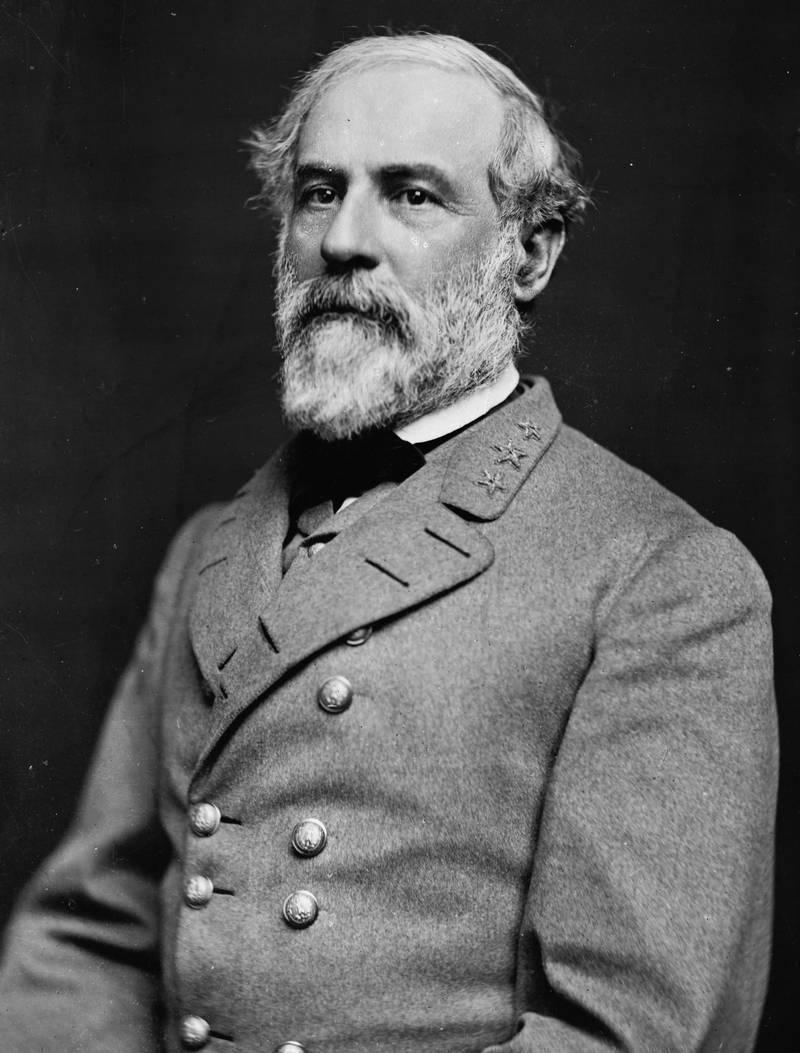

Lee, Seven Days Battles, and Civil War: At the outbreak of war, Robert E. Lee was appointed

to command all of Virginia's forces, but upon the formation

of the Confederate States Army, he was named one of its first five full generals. Lee did not wear the insignia of a Confederate

general, but only the three stars of a Confederate colonel, equivalent to his last U.S. Army rank. He did not intend to wear

a general's insignia until the Civil War had been won and he could be promoted, in peacetime, to general in the Confederate

Army. Lee's

first field assignment was commanding Confederate forces in western Virginia,

where he was defeated at the Battle of Cheat Mountain and was widely blamed for Confederate setbacks. He was then sent to organize the coastal defenses along the Carolina and

Georgia seaboard, where he was hampered

by the lack of an effective Confederate navy. Once again blamed by the press, he became military adviser to Confederate President

Jefferson Davis, former U.S. Secretary of War. While in Richmond,

Lee was ridiculed as the 'King of Spades' for his excessive digging of trenches around the capitol. These trenches, however,

would play an important role in battles near the end of the war.

| General Robert E. Lee in 1863 |

|

| General Robert E. Lee in 1863 |

In

the spring of 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign, the Union Army of the Potomac under George McClellan advanced upon Richmond from Fort Monroe,

eventually reaching the eastern edges of the Confederate capitol along the Chickahominy

River. Following the wounding of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston at the Battle

of Seven Pines, on June 1, 1862, Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia, his first opportunity to lead an army

in the field. Newspaper editorials of the day objected to his appointment due to concerns that Lee would not be aggressive

and would wait for the Union army to come to him. Early in the war his men referred to him as "Granny Lee" because of his

allegedly timid style of command. After the Seven Days Battles and until the end of the war, however, his men respectively

referred to him as "Marse Robert." He oversaw substantial strengthening of Richmond's

defenses during the first three weeks of June and then launched a series of attacks, the Seven Days Battles, against McClellan's

forces. Lee's attacks resulted in heavy Confederate casualties and they were marred by clumsy tactical performances by his

subordinates, but his aggressive actions thwarted McClellan, who retreated to a point on the James River

where Union naval forces were in control. These successes led to a rapid turn-around of public opinion and the newspaper editorials

quickly changed their tune on Lee's aggressiveness. Following his defeat at Gettysburg, Lee

sent a letter of resignation to Pres. Davis on August 8, 1863, but Davis

refused Lee's request. On January 31, 1865, Lee was promoted to general-in-chief of Confederate forces.

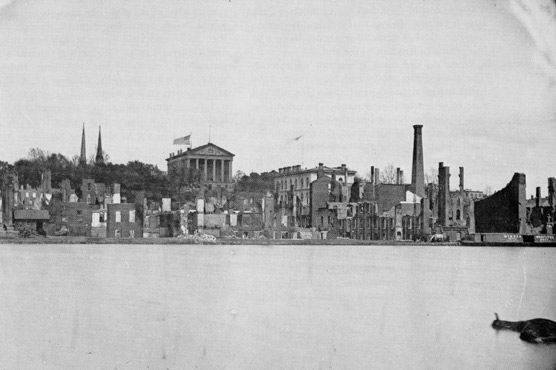

| Richmond, Virginia, in 1865 |

|

| (Richmond National Battlefield Park) |

Richmond in History

and Memory: The Civil War (1861-1865) remains the central, most defining event

in American history. Richmond, Virginia,

was at the heart of the conflict. As the industrial and political capitol of the Confederacy, Richmond was the physical and psychological prize over which two mighty American armies contended

in bloody battle from 1861 to 1865. At stake were some of the founding principles of the United States as the growing nation divided over the existence and expansion of

slavery. Only after the new Confederacy fired on a federal fort in Charleston harbor and Lincoln had called for troops to preserve the Union, did Virginia

join the Confederacy. As war began, neither side anticipated the brutal clashes and home front destruction that brought death

or injury to more than one million Americans and devastation to a broad landscape, much of it in Virginia.

(Photo) Waterfront view of Richmond’s capitol building after the evacuation and fire

in 1865.

Cannon boomed within earshot

of Richmond.

All of its residents saw their lives transformed. Wartime Richmond,

swollen by government, the military, refugees, prisoners, and the wounded, lived with anxiety and hope. Martial law and rationing

were routine. Disease claimed thousands.

Landowners outside Richmond saw their farms converted into battlefields. Previously unknown

place-names like Cold Harbor, Gaines’ Mill, Malvern Hill, and New Market Heights attained national significance for the key

battles that were fought in the vicinity of Richmond. Naval

military history was made at the Battle of Drewry's Bluff. Robert E. Lee fought his first battle as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia at Beaver Dam Creek in 1862; Ulysses

S. Grant’s army experienced unprecedented futility on the bloody fields of Cold Harbor.

Titans tangled repeatedly here. Earthworks scarred miles of farmland. Wheat fields became killing fields. Cemeteries started

dotting the landscape.

On April 4 and 5, 1865,

President Lincoln made a remarkable visit to Richmond as he

pressed to conclude the war that had cost more than 620,000 lives “with malice toward none, with charity for all…”

His assassination, just days later, portended a less charitable course for the aftermath.

Today, the Richmond

National Battlefield Park

preserves more than 1900 acres of Civil War resources in 13 units, including the main visitor center at the famous Tredegar

Iron Works and the Chimborazo Medical Museum, on the site of Chimborazo

Hospital. Advance to Battle of Malvern Hill.

(Sources and related reading below.)

Recommended

Reading: To The Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign, by Stephen W. Sears. From Kirkus Reviews: In George B. McClellan

(1988) and his work editing the papers of the Union general, Sears established himself as the critical but indispensable authority

on flawed ``Little Mac.'' Now, in a stirring prequel to Landscape Turned Red (1983), his superb account of the Battle of Antietam,

the author reaffirms his mastery of historical narrative. In March 1862, the egotistical but timorous McClellan was prodded

by Lincoln into finally launching the first major offensive by the Army of the Potomac.

Instead of marching directly overland from Washington, McClellan used Federal sea power to

advance on Richmond by way of the peninsula between the York

and James Rivers. Continued below…

The "Grand

Campaign,'' however, soon belied its creator's Napoleonic pretensions by becoming a three-and-a-half-month nightmare of feints

and pitched battles, ultimately engaging up to a combined quarter-million men on both sides and leaving one of every four

men dead, wounded, or missing. Using hundreds of eyewitness accounts, Sears demonstrates how the most creative use of military

technology (ironclad warships, 200-pounder rifled cannon, battlefield telegraph, and aerial reconnaissance) existed side by

side with the most appalling mismanagement (Stonewall Jackson's uncharacteristic lethargy; McClellan's mistaken belief that

the numerically inferior rebels possessed a two-to-one manpower advantage; out-of-sync attacks by both Confederate and Union

generals). Above all, though, Sears casts the campaign as a clash of wits and wills between McClellan--whom he accuses of

losing ``the courage to command''--and Robert E. Lee--who, upon succeeding the wounded Joseph E. Johnson as head of the Army

of Northern Virginia, seized the initiative, repulsed the assault in the series of ``Seven Days'' battles, and began his long

journey into legend. An authoritative, ironic, and stirring addition to Civil War annals. “…[No] serious study

of the Peninsula Campaign is possible without this book.” Americancivilwarhistory.org

Recommended

Reading: Extraordinary Circumstances: The Seven Days Battles (Library Binding). Description: EXTRAORDINARY CIRCUMSTANCES tells the story of the Seven Days Battles,

the first campaign in the Civil War in which Robert E. Lee led the Army of Northern Virginia. One of the most decisive military

campaigns in Western history, the Seven Days were fought in the area southeast of the Confederate capitol of Richmond from

June 25 to July 1, 1862--and began a string of events leading to the Emancipation Proclamation and the shift toward total

war.

Recommended

Reading: The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula and the

Seven Days (Military Campaigns of the

Civil War). Description: The Richmond campaign of April-July

1862 ranks as one of the most important military operations of the first years of the American Civil War. Key political, diplomatic,

social, and military issues were at stake as Robert E. Lee and George B. McClellan faced off on the peninsula between the

York and James Rivers. The climactic clash came on June 26-July 1 in what became known as the Seven Days battles, when Lee,

newly appointed as commander of the Confederate forces, aggressively attacked the Union army. Casualties for the entire campaign

exceeded 50,000, more than 35,000 of whom fell during the Seven Days. Continued below…

This

book offers nine essays in which well-known Civil War historians explore questions regarding high command, strategy and tactics,

the effects of the fighting upon politics and society both North and South, and the ways in which emancipation figured in

the campaign. The authors have consulted previously untapped manuscript sources and reinterpreted more familiar evidence,

sometimes focusing closely on the fighting around Richmond and sometimes looking more broadly at the background

and consequences of the campaign.

Recommended

Reading: Seven Days Before Richmond: McClellan's Peninsula Campaign

of 1862 and its Aftermath (Hardcover).

Description: Combining meticulous research with a unique perspective, Seven Days Before Richmond examines the 1862 Peninsula

Campaign of Union General George McClellan and the profound effects it had on the lives of McClellan and Confederate General

Robert E. Lee, as well as its lasting impact on the war itself. Continued below…

Rudolph Schroeder's

twenty-five year military career and combat experience bring added depth to his analysis of the Peninsula Campaign, offering

new insight and revelation to the subject of Civil War battle history. Schroeder analyzes this crucial campaign from its genesis

to its lasting consequences on both sides. Featuring a detailed bibliography and a glossary of terms, this work contains the

most complete Order of Battle of the Peninsula Campaign ever compiled, and it also includes the identification of commanders

down to the regiment level. In addition, this groundbreaking volume includes several highly-detailed maps that trace the Peninsula

Campaign and recreate this pivotal moment in the Civil War. Impeccably detailed and masterfully told, Seven Days Before Richmond

is an essential addition to Civil War scholarship. Schroeder artfully enables us to glimpse the innermost thoughts and motivations

of the combatants and makes history truly come alive.

Recommended

Reading: The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: A Military Analysis (Hardcover). Description: The largest offensive of the Civil War, involving army,

navy, and marine forces, the Peninsula Campaign has inspired many history books. No previous work, however, analyzes Union

general George B. McClellan's massive assault toward Richmond

in the context of current and enduring military doctrine. The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: A Military Analysis fills this void.

Background history is provided for continuity, but the heart of this book is military analysis and the astonishing extent

to which the personality traits of generals often overwhelm even the best efforts of their armies. Continued below…

The Peninsula

Campaign lends itself to such a study. Lessons for those studying the art of war are many. On water, the first ironclads forever

changed naval warfare. At the strategic level, McClellan's inability to grasp Lincoln's grand objective becomes evident. At the operational

level, Robert E. Lee's difficulty in synchronizing his attacks deepens the mystique of how he achieved so much with so little.

At the tactical level, the Confederate use of terrain to trade space for time allows for a classic study in tactics. Moreover,

the campaign is full of lessons about the personal dimension of war. McClellan's overcaution, Lee's audacity, and Jackson's personal exhaustion all provide valuable insights for today's

commanders and for Civil War enthusiasts still debating this tremendous struggle. Historic photos and detailed battle maps

make this study an invaluable resource for those touring the many battlegrounds from Young's Mill and Yorktown through Fair Oaks to the final throes of the Seven Days' Battles. Kevin Dougherty, Hattiesburg,

Mississippi, is professor of military science at the University of Southern Mississippi. He is the

author of The Coastal War in North and South Carolina. J.

Michael Moore, Yorktown, Virginia, is the registrar of Lee Hall Mansion.

Sources: National Park Service; National Archives; Library of Congress; Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies; Civil War Trust, civilwar.org; Abbot, Henry L. (2010). Siege Artillery in the Campaigns Against Richmond:

With Notes on the Fifteen-Inch Gun. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-164-86770-9; Abbott, John Stevens Cabot

(2012) [1866]. The history of the Civil War in America: comprising a full and impartial account of the origin and progress

of the rebellion, of the various naval and military engagements, of the heroic deeds performed by armies and individuals,

and of touching scenes in the field, the camp, the hospital, and the cabin. Charleston, South Carolina: Gale, Sabin Americana.

ISBN 1-275-83646-1; Brasher, Glenn D. (2012). The Peninsula Campaign & the Necessity of Emancipation. Chapel Hill, North

Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-3544-7; Burton, Brian K. (2010). Extraordinary Circumstances: The

Seven Days Battles. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-10844-6; Burton, Brian K. The Peninsula &

Seven Days: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8032-6246-1; Department of Military

Art and Engineering (1959). "West Point Atlas of American Wars". New York: Frederick A. Praeger. OCLC 5890637; Dougherty,

Kevin (2010). The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: A Military Analysis. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi.

ISBN 1-60473-061-7; Editors of Time-Life Books. Lee Takes Command: From Seven Days to Second Bull Run. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life

Books, 1984. ISBN 0-8094-4804-1; Eicher, David J. (2002). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. London:

Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-1846-9; Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger,

1959. OCLC 5890637; Freeman, Douglas S. (1936). R. E. Lee: A Biography, Volume 2. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. ISBN 0-6841-5483-8;

Freeman, Douglas S. (2001). Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-6848-5979-3; Gabriel,

Michael P. "Battle of Malvern Hill". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities; Gallagher, Gary W. (2008).

The Richmond Campaign of 1862: The Peninsula & the Seven Days. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina

Press. ISBN 0-8078-5919-2; Harsh, Joseph L. Confederate Tide Rising: Robert E. Lee and the Making of Southern Strategy, 1861–1862.

Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-87338-580-2; Hattaway, Herman (1997). Shades of Blue and Gray: An Introductory

Military History of the Civil War. Columbia, Montana: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1107-0; Kennedy, Frances H.,

ed. The Civil War Battlefield Guide. 2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. ISBN 0-395-74012-6; Martin, David G. The

Peninsula Campaign March–July 1862. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1992. ISBN 978-0-938289-09-8; Miller, William

J. The Battles for Richmond, 1862. National Park Service Civil War Series. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service

and Eastern National, 1996. ISBN 0-915992-93-0; Rafuse, Ethan S. McClellan's War: The Failure of Moderation in the Struggle

for the Union. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-253-34532-4; Robertson, James I., Jr. Stonewall Jackson:

The Man, The Soldier, The Legend. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-02-864685-1; Roland, Charles P. (1995). Reflections

on Lee: A Historian's Assessment. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0719-9; Rollyson, Carl E. Paddock,

Lisa O. Gentry, April (2007). Critical Companion to Herman Melville: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York:

Infobase Publishing. ISBN 1-4381-0847-8; Salmon, John S. (2001). The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide (illustrated

ed.). Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4; Savas, Theodore P.; Miller, William J. (1995). The

Peninsula Campaign of 1862: Yorktown to the Seven Days, volume 1. Campbell, California: Woodbury Publishers. ISBN 1-882810-75-9;

Savas, Theodore P.; Miller, William J. (1996). The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: Yorktown to the Seven Days, volume 2. Campbell,

California: Woodbury Publishers. ISBN 1-882810-76-7; Savas, Theodore P.; Miller, William J. (1997). The Peninsula Campaign

of 1862: Yorktown to the Seven Days, volume 3. Campbell, California: Woodbury Publishers. ISBN 1-882810-14-7; Sears, Stephen

W. (1992). To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign. New York: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0-89919-790-6; Sears, Stephen

W. (2003). Landscape Turned Red: The Battle of Antietam (reprint ed.). New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-34419-5;

Settles, Thomas M. (2009). John Bankhead Magruder: A Military Reappraisal. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University

Press. ISBN 0-807133-91-4; Snell, Mark A. (2002). From First to Last: The Life of Major General William B. Franklin (illustrated

ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-8232-2149-0; Sweetman, Jack (2002). American Naval History: An Illustrated

Chronology of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, 1775–present (illustrated ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press.

ISBN 1-55750-867-4; Webb, Alexander S. The Peninsula: McClellan's Campaign of 1862. Secaucus, NJ: Castle Books, 2002. ISBN

0-7858-1575-9. First published 1885; Wert, Jeffry D. General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier:

A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 0-671-70921-6; Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization

and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-36453-1; Wheeler, Richard

(2008). Sword Over Richmond: An Eyewitness History of McClellan's Peninsula Campaign. Scranton, Pennsylvania: Random House

Value Publishing. ISBN 0-7858-1710-7; Wise, Jennings Cropper (1991). The Long Arm of Lee: The History of the Artillery of

the Army of Northern Virginia, Volume 1: Bull Run to Fredericksburg. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN

0-8032-9733-5.

|