|

First Battle of Saltville

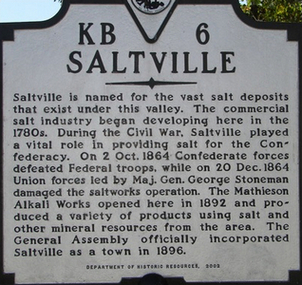

Saltville Civil War History

| Battle of Saltville |

|

| First Battle of Saltville |

First Battle of Saltville

Other Names: Battle of Saltville; First Battle of the Saltworks;

Battle of Cedar Branch

Location: Smyth County, Virginia

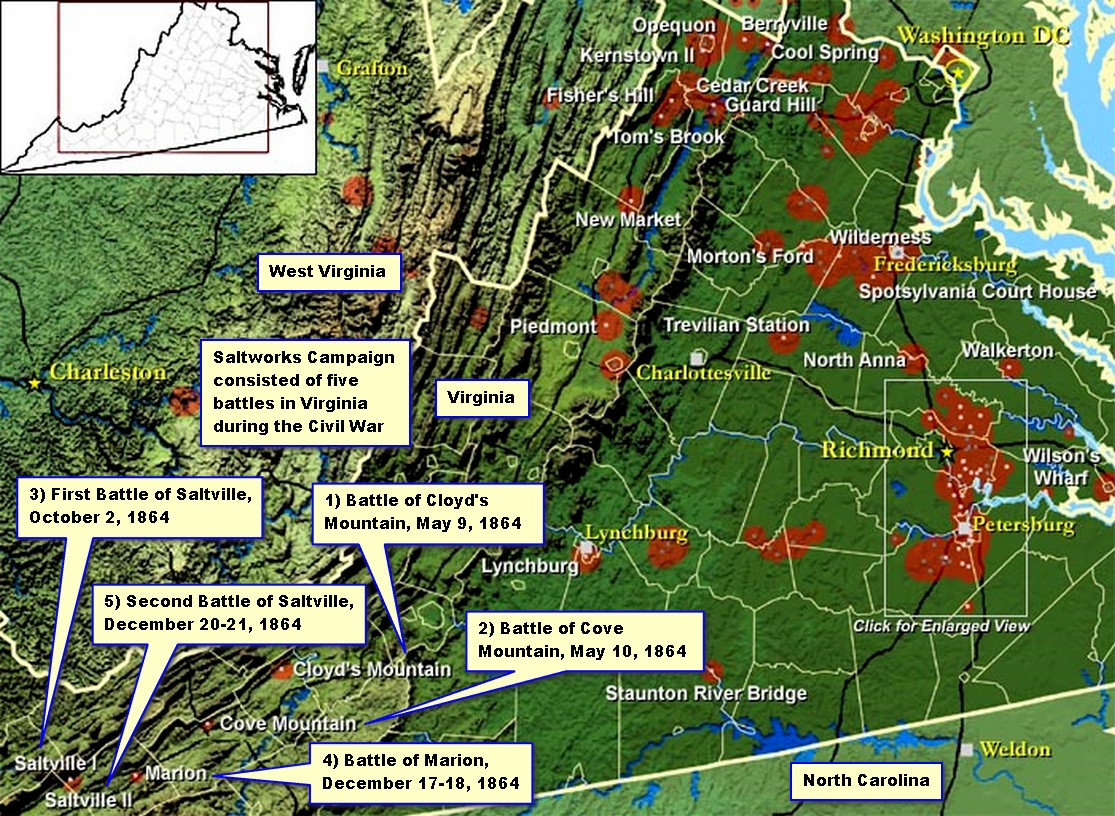

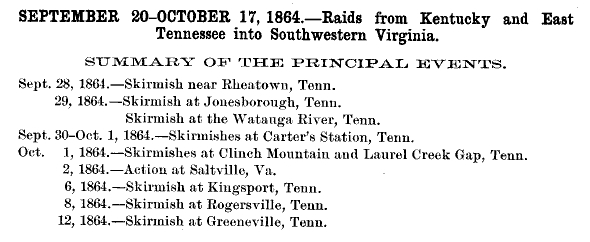

Campaigns: Burbridge’s Raid into Southwest Virginia (September-October

1864); Virginia Saltworks Campaign (May-December 1864)

Date(s): October 2, 1864

Principal Commanders: Brevet Maj. Gen. Stephen Burbridge

[US]; Brig. Gen. Alfred E. Jackson [CS]

Forces Engaged: 8,000 (US 5,200; CS 2800)

Estimated Casualties: 448 (US 348; CS 100)

Result(s): Confederate victory

Summary: The First Battle of Saltville was fought during the

Saltworks Campaign and was the third of five Union attempts to destroy the salt capitol of the Confederacy. In an attempt

to destroy the salt production near Saltville, Virginia, Brevet Maj. Gen. Stephen Burbridge led an army of 5,200 strong.

In this six hour fight, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., Union cavalry, including one of only six regiments of U.S. colored

cavalry raised during the war, would dismount and engage a well-entrenched Confederate force only to be repulsed from

the field. Brig. Gen. John Echols, commanding Confederate

forces at Saltville, would masterfully employ a series of delaying actions against two large Union armies, Burbridge

and Gillem, in a successful attempt to buy time and add the much needed reinforcements to his patchwork command of 400.

Burbridge was delayed at Clinch Mountain and Laurel Gap by a small Confederate

contingent, enabling Brig. Gen. Alfred E. Jackson to concentrate troops near Saltville to engage. On the morning of October

2, 1864, the Federals attacked but made little headway as Confederate reinforcements continued to arrive during

the day. After day-long fighting and after suffering heavy losses on their left, the Federals would dig in on the side

of a steep slope. Having committed a series of frontal assaults up the rugged terrain, and with ammunition now exhausted, Burbridge retreated early on the 3rd without accomplishing his objective, but as he was retiring

in what rapidly turned into a disorderly retreat, his rear units were struck by Confederate forces. During the hasty

withdrawal, Burbridge abandoned his wounded, the majority being colored troops, and Confederate soldiers under orders

from Brig. Gen. Felix Robertson, summarily murdered the captured and wounded black soldiers and white officers. The action

quickly became known as the Saltville Massacre.

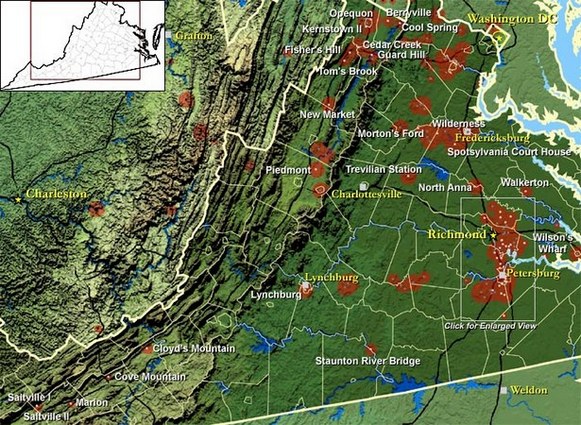

| Civil War Battle of Saltville Map |

|

| Battle of Saltville Map |

| Southwestern Virginia and the Civil War |

|

| Southwestern Virginia was vital to the Southern war effort |

Introduction: This contest was a microcosm of the

Brothers' War, for opposing sides had recruited from some of the same counties in Kentucky, and this action involved colored

cavalry, West Point and VMI graduates, and the highest ranking official to ever commit treason against the United States.

The youngest vice president in history, John C. Breckinridge, also cousin to Mary Todd Lincoln, was a Kentuckian who took up arms

as a Confederate general, and Union Gen. George Crook, who would later become a controversial figure during the Indian

wars, was roommate to none other than "Stonewall" Jackson while attending West Point. "Stonewall" would meet his fate

by friendly fire at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863, but Crook would rise through the ranks to the permanent grade

of major general, and President Grover Cleveland would appoint him commander of the "Military Division of the Missouri" in

1888. This was indeed Civil War.

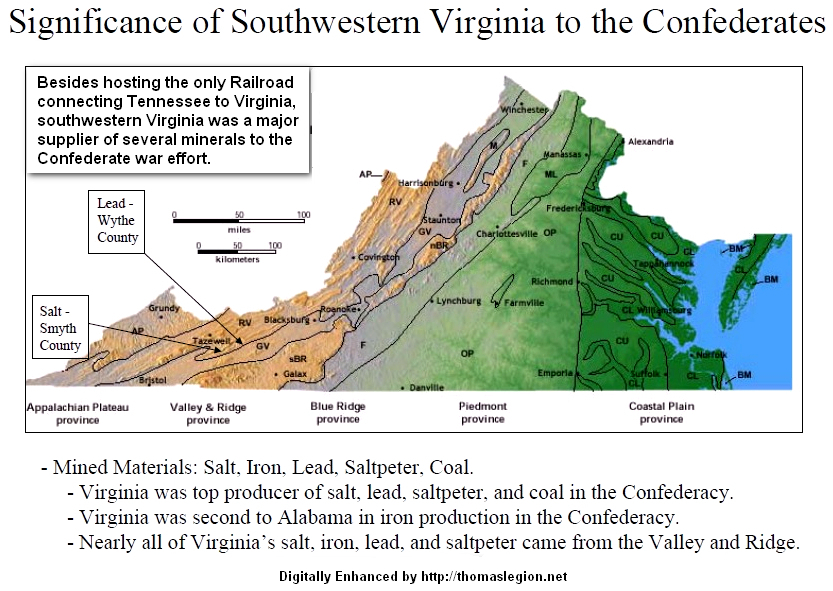

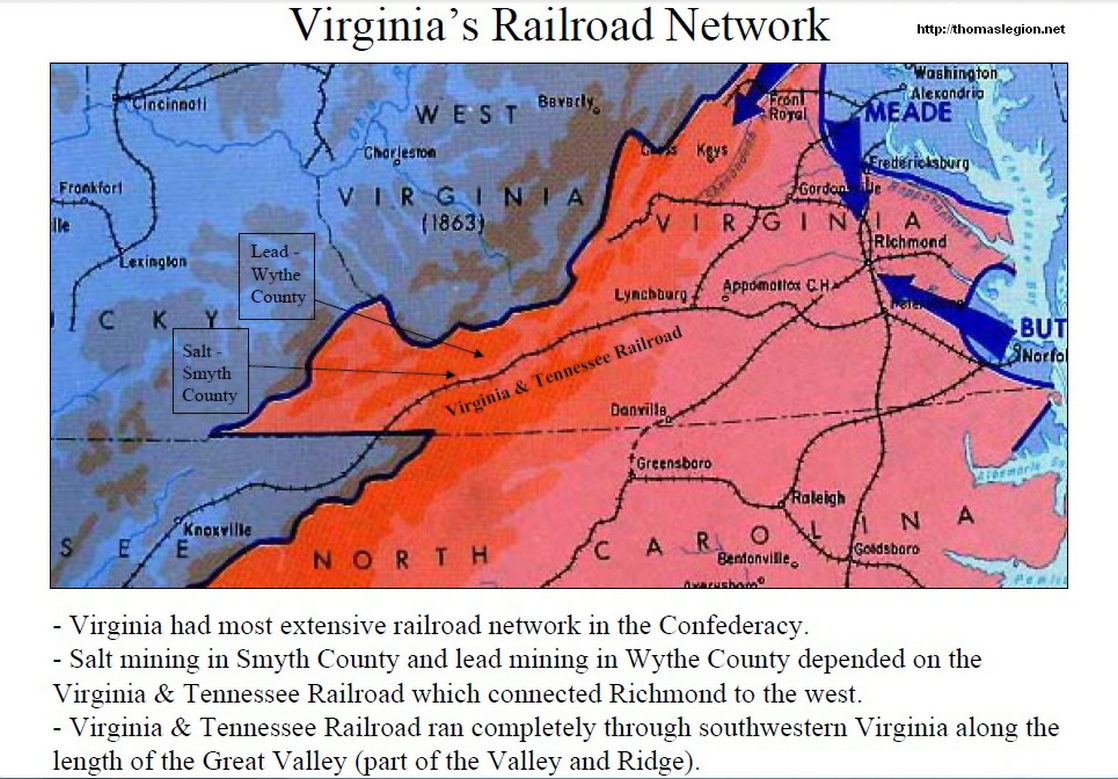

Southwestern Virginia was important to the Confederacy though it experienced

few battles. The Virginia and Tennessee Railroad ran through the region, connecting the eastern and western theaters

of operation. It also hosted salt and lead mines that were vital to the Southern war effort. Located in northwestern

Smyth County, Virginia, Saltville, during its peak war year in 1864, manufactured about 4,000,000 bushels — 200,000,000

pounds — an estimated two-thirds of all the salt required by the Confederacy. No wonder, then, that this remote area

found itself in the 1860s thrust into the very center of military activity in southwestern Virginia as North and South clashed

over these vital salt operations. Salt was necessary for preserving food, for sustaining life itself, and it was an integral

part of the leather curing process. An army may march and fight well on a full stomach, but without leather it

would have to do it with the poorest quality boots and footwear, and absent leather there would be no saddles and the

much needed tack for horses.

In September 1864, Union Brig.

Gen. Alvan Gillem planned a raid from his base in East Tennessee, and he requested the assistance of Brevet Maj. Gen. Stephen

Burbridge, commanding District of Kentucky. Burbridge thwarted Gillem’s plan by requesting permission from Union

Army Chief of Staff General Henry Halleck to launch an expedition toward Saltville from Kentucky while Gillem threatened the

area from the southeast. Although Burbridge would be repulsed in his attempt to strip the Confederacy of its much needed salt, Gen.

George Stoneman would be successful just a few months later in December.

| Battle of Saltville Map |

|

| Saltville Civil War Battlefield Map |

Background: The First Battle of Saltville, October

2, 1864, was the third of five attempts to destroy what was referred to as the salt capitol of the Confederacy. This engagement was fought mainly with Kentucky men. While the Union would employ all cavalry

and mounted units, the Confederates would throw every available unit, from militia to regular, into the fray. With the

exception of the 11th Michigan and 12th Ohio Cavalries, the Union command

was formed of Kentucky units, while the Confederate forces were of Kentucky, Virginia, Georgia, and Tennessee.

Stationed at Point Burnside,

Kentucky, the IV Brigade, consisting of the 11th Michigan and 12th Ohio, was to assist in the expected fight against

Maj. Gen. Joe Wheeler, but the brigade was reassigned to Burbridge for the Saltville raid. The 5th United States Colored Cavalry, one of only six colored cavalry units

formed during the war, was being formed at Camp Nelson, in the Bluegrass State, when Colonel James S. Brisbin, commanding,

agreed with Brevet Maj. Gen. Stephen G. Burbridge's request to prematurely press the green recruits into service. The

5th USCC was then placed under command of Colonel James F. Wade, who would later command the 6th USCC, and attached to

the IV Brigade for the Virginia incursion.

Although Kentucky, a Border State during the war, had declared its

neutrality once hostilities began, the several thousand Kentucky men in blue who were trekking through southwestern

Virginia were determined to crush the Rebellion at every turn and town.

By late September, Union Bvt.

Maj. Gen. Stephen G. Burbridge, the widely despised military governor of Kentucky, decided to move on Saltville. On September 20, Burbridge left Kentucky with some 5,200 strong, including 600

of the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry. In East Tennessee, Brig. Gen. Alvan Gillem commanded a Union army of 1,650, while Brig.

Gen. Jacob Ammen led a force of 800, and on Sept. 28, the combined command, numbering 2,450, continued

to move through the region while fighting the enemy. The two brigadiers had planned to move on the Confederates

at Saltville in an 1800s pincer style movement with Burbridge, but because Gillem and Ammen would become involved

in a series of skirmishes in the Tennessee mountains, the force would not be present for the engagement but would

serve as a diversion.

Burbridge chose a particularly difficult invasion route into southwestern

Virginia, moving along the Levisa Fork of the Big Sandy River through the rugged, deeply dissected plateaus country. The Federals

moved over an especially rugged mountain on September 28 at night during a thunderstorm. Perhaps as many as eight men and

their mounts fell to their deaths from the precipitous trail. Others had to be rescued with ropes.

Meanwhile, on the Confederate

side, Saltville's defense was the responsibility of the newly reorganized Department of Southwest Virginia and East

Tennessee. The Department's commander, Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, like opposing commander Burbridge, a Kentuckian,

had been campaigning in the Shenandoah Valley under Lt. Gen. Jubal Early but was hastening back to southwestern Virginia

to confront the Union advance. For less than one month, Brig. Gen. John Echols, a VMI graduate, had been acting commander

during Breckinridge's absence. As 5,200 strong were slowly trekking southward, the patchwork

force that awaited them numbered 400. During September, Echols sent dispatches throughout the region requesting units to

come to his aid, and while he personally rode to nearby towns rallying every

available man for the defense of the city of salt, he temporarily placed Brig. Gen. Alfred E. Jackson in command.

To counter the large Federal army moving in his direction, as reported

by scouts, a series of delaying actions were put into motion by Brig. Gen. John Echols.

While Echols was commanding Confederate forces at Saltville

in September 1864, he received dispatches indicating that Union Bvt. Maj. Gen. Burbridge had departed Lexington, Kentucky,

and was en route to Saltville, with orders to destroy it. Several reports placed the Federal force at

6,000 to 8,000 strong, numbers that were more than troubling to Echols, who commanded a battalion sized force of 400

men at Saltville, which was scarcely enough to check the Federal advance. But the situation was more dire, because Brig. Gen.

Gillem was in East Tennessee and his intention was to advance his army on and lay waste to the prized

saltworks. Echols needed men, he needed reinforcements immediately. Victorious, "Stonewall" Jackson was often confronted

with two or more much larger armies during the 1862 Valley Campaign, and he would rapidly strike and cripple one army

before moving and attacking the next force. Straight from "Stonewall's" playbook, Echols sent some 300 cavalry to

Bull's Gap, TN, to punish and harass the enemy. All available units, meanwhile, were ordered to report to Echols

at Saltville. Maj. Gen. Breckinridge, who had been fighting in the Shenandoah Valley

under Lt. Gen. Early, was returning to his old command at Saltville. Confederate Brig. Gen. Johns S. Williams also

responded from Bristol, TN, and was moving his vanguard force of 1,700 soldiers

into southwestern VA, while 300 Virginia reserves, under Lieutenant Colonel Preston, were en route by train.

George

D. Mosgrove, a Kentucky Confederate soldier, described Saltville as a “natural fortress” with hills and ridges

in concentric circles, which greatly aided in the Confederate defenses. His account of the battle of Saltville

begins in the summer of 1864, when rumors circulated that Bvt. Maj. Gen. Stephen Burbridge’s forces were marching

toward the saltworks on a parallel course with the Confederate forces under Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan. In late

September, closer to the time of the actual battle, Mosgrove writes that scouts reported a force of 6,000 to 8,000

cavalry with six to ten pieces of artillery coming from Kentucky, commanded by Gen.

Burbridge, Gen. E.H. Hobson, and Colonel Charles Hanson. In addition, the scouts reported seeing two possible African-American

brigades, which were in fact the 5th and the beginnings of the 6th United States Colored Cavalry (USCC). Gen. Basil Duke,

a member of Morgan’s army, also presents an account of the battle of Saltville. He notes that in addition to the threat

presented by Burbridge, two other Union generals, Jacob Ammen and A. C. Gillem, were advancing toward Saltville,

but were coming from Knoxville, Tennessee, as opposed to the Kentucky route Burbridge was taking.

In response to the scout's report, Confederate Colonel Henry Giltner sent

Colonel Edward Trimble with 150 men to Richlands, 40 miles from Saltville, to head off the Union forces. Colonel Trimble then

instructed Giltner to take 100 of his men to the gap in Paint Lick Mountain to protect the main turnpike road running

through that gap, and to provide reinforcements should Trimble need to fall back. Burbridge sent a battalion to Jeffersonville

(present-day Tazewell), on the Confederate right, to try another approach toward the saltworks. Giltner then sent Captain

Bart Jenkins with an additional company to meet the Union forces at Jeffersonville. Trimble did skirmish with Federal forces

at Cedar Bluff and was forced to fall back. The consolidated Confederate force of 300 men, under Giltner, was then pushed

back to the summit of Clinch Mountain, and attempted to hold that mountain pass into the valley. The Union army sent 500 men

around Paint Lick Mountain toward Jeffersonville, flanking the gap.

| Saltville Civil War History |

|

| Battle of Saltville |

| Principal Events of Union Army |

|

| Events Surrounding Battle of Saltville |

Battle: The

battle would open on October 2nd with Bvt. Maj. Gen. Stephen Burbridge committing the greater portion of his force,

but Confederate resistance was strong, much stronger than the Union general anticipated, so in what would quickly unravel

into a disjoined assault he soon threw the bulk of his reserves into the fray. Some 4,000 Federals, the greater

part of his 5,200 strong command, including 400 colored cavalry, would engage in the action.

Of note was the unproven 5th

United States Colored Cavalry that was being formed at Camp Nelson, Kentucky, when it was pressed into service. The recruits of the 5th, mainly

ex-slaves, would receive their baptism of fire and perform like seasoned veterans as more than 100 fell while charging

Confederate works, but it would be three weeks after the battle, Oct. 24, 1864, that the 5th would officially

become a unit. En route from Kentucky, the colored soldiers, as well as

their white officers had been the subject of much ridicule and many insulting remarks by white Union troops of the command.

Colored soldiers will not fight were among the jeers and taunts, but though recipients of such remarks they refused to

hurl insults in return.

Burbridge had eagerly moved the raw recruits of the forming 5th into

Virginia, but knowing that the colored troops lacked the necessary training for combat, the Union commander also

bestowed upon these soldiers what was considered substandard equipment for 1864 cavalrymen, thus promulgating an environment

ripe for the bloodbath to come.

Whereas the white Union cavalry and mounted units of the division were

atop proven chargers and armed with 7-shot Spencer carbines (some had the Ballard or Starr carbine) and one or more

revolvers, the unproven black troops were riding untested mounts, which were intended for the purpose of drilling only, and

armed with outdated single-shot, muzzle-loading Enfields.

Of the 600 men forming the 5th USCC, 100 were left behind sick, 100 remained in the valley to hold the horses, leaving

400 effectives for this fight. And of the 350 Union soldiers who fell at Saltville,

the 5th USCC suffered 33% of the total Federal losses. While fighting dismounted on the Federal left, the 5th sustained

28% casualties, during this single action, which would be the highest loss suffered by any Union unit in the action

at Saltville. I have seen white troops fight in 27 battles, Brisbin later reported, and I never saw any fight better.

Burbridge marched his command across the mountains, into southwestern VA, where he met and fought small Confederate units from Sept.

30 to Oct. 1, when his tired command arrived at Laurel Gap, some 4 miles from Saltville. Camping for the night, Burbridge wanted

a well-rested force for the assault on Saltville in the morning. Whereas only 400 Southern soldiers were in position

to defend the works on the evening of Oct. 1, Brig. Gen. Williams would arrive with his force early on Oct. 2, and ready for

action. Soldiers indeed responded to the many pleas from Echols, and while the fight raged, troops would continue to

stream onto the battlefield, thus swelling the size of the Confederate army to some 2,800. If Burbridge would have opened

the battle on Oct. 1, his 5,200 strong would have easily brushed aside the small Confederate force of 400.

| Battle of Saltville Civil War History |

|

| Confederate units were informed to hold Saltville at all hazards |

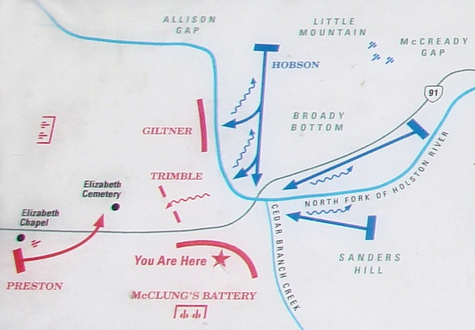

| Map of Union and Confederate Armies at Saltville |

|

| Map of First Saltville Battlefield on October 2, 1864 |

On the evening

of September 30th, Captain Edward Guerrant made his headquarters at the home of George Gillespie, near the grounds of Gen.

Bowen. Late at night, the captain was awakened with news that the Union forces were firing on Gen. Bowen’s property.

Captain Guerrant responded by sending a member of the 10th Kentucky Cavalry to warn Colonel Giltner, and by sending

the 4th Kentucky Cavalry to picket toward the Union. That same day, Lt. Col. Robert

Preston also arrived in Saltville with his reserves. He was unaware of the strength of the Union forces approaching the town;

his orders had simply been to reach Saltville as quickly as possible, according to the account of one of his reservists and

friends.

As Burbridge approached Saltville on October 1, Breckinridge's chief

lieutenant, Brig. Gen. John Echols, was calm while quickly pulling together scattered forces for the defense of the saltworks.

In Saltville itself, command fell to Brig. Gen. Alfred E. Jackson, derisively

called "Mudwall" by his own men, a sobriquet he apparently earned by his ineptness. But "Mudwall," to his credit, prepared

Saltville's defenses well, constructing fortifications and rifle pits, and when the Yankees finally attacked, they

found the rebel soldiers firmly entrenched on the hills north and west of town.

A. E. Jackson, a Tennessean, was a farmer who owned 20 slaves prior

to hostilities. Jackson lacked any military service, and unlike the grads of

VMI and West Point, he had no formal training. As a brigade commander, his inexperience was a contributing factor to poor

morale in the ranks, causing from simple complaints to desertion. Whereas it was common practice to openly punish and

discipline slaves, Jackson would publicly rebuke officers in the presence of enlisted men, which was considered

a forbidden practice. He is often confused with William Lowther "Mudwall" Jackson Jr., a Confederate general and second cousin

to "Stonewall" Jackson.

On October 1st, the evening before the battle, the Federal soldiers camped on the grounds of Gen. Bowen,

two miles outside of the Confederate position within Saltville. At that time, only the Virginia reserves were actually stationed

within the town, with but a few pieces of artillery. Brig. Gen. John S. Williams was collecting as many men as possible

at Castle Woods, not far from Saltville, and while Brig. Gen. Echols was rounding up soldiers from nearby Abington, Brig, Gen. Alfred Jackson arrived at Saltville and supervised the fortifications under construction.

The 64th Virginia Battalion, under Lieutenant Colonel Robert Smith with

250 men, and the 10th Kentucky Cavalry were both on the summit of Flat Top Mountain, guarding possible entrances to Saltville.

Following a skirmish with Federal troops, the regiments were forced to fall back to Laurel Gap. In addition, the 4th and 10th

Kentucky Mounted Rifles were already posted at Laurel Gap. Laurel Gap is surrounded on either side by tall cliffs, thought

to be inaccessible, and not to be scaled. However, the mounted rifles were posted as far up the left cliff as possible, and

the 64th battalion was stationed on the right. Colonel Trimble was also sent up behind the mountain with his battalion. Late

in the afternoon, Union forces secured passage through the mountain by pushing the 64th Battalion from its position and crossing

on the right. The remaining Confederate forces then retreated to Saltville. At Broadford the road into the town forked and

split into two separate roads, both leading southward into the valley toward Saltville. Giltner took the 64th Virginia

and the 10th Kentucky Mounted Rifles across the Holston River, and ordered Trimble to take the 4th and 10th Kentucky Cavalry

down the main river road, thus covering both avenues of approach. By midnight, the entire Federal force was able to cross

the mountain through Laurel Gap.

The battle opened on the cold morning of October 2nd with the Federals attacking pickets

and skirmish lines. The 4th and 10th Kentucky Cavalry under Colonel Trimble then crossed over to ground occupied by Colonel

Giltner to act as reinforcements. Colonel Trimble’s men then attacked the Union forces, and fell back slowly. Meanwhile,

the Union forces charged the 4th Kentucky Cavalry and skirmished with them for half an hour. Part of the 4th occupied a position

high on the hill near “Governor” Sanders’ house, where a contingent of 250 men, that had arrived in

advance of Brig. Gen. John Williams' main body to reinforce the Confederates, had moved onto the field under

Gen. Felix Roberston, who had just arrived himself with detachments of the 8th and 11th Texas Cavalry. Notorious Confederate guerrilla Champ Ferguson and several of his guerrillas also arrived

with Robertson.

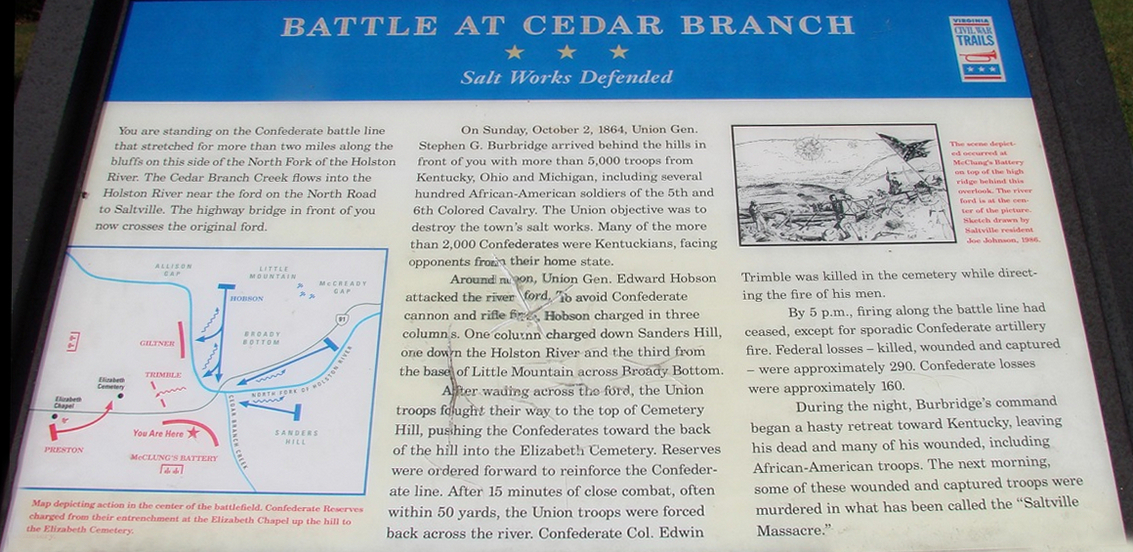

| Union Approach Up Cedar Branch |

|

| View of Union approach up steep embankment at Battle of Saltville |

At this point, Mosgrove’s account lists fighting and changing of positions,

with a bit of confusion as to which regiment was moving where. Ultimately, the Confederate forces ended up positioned all

along the ridges. Gen. Williams was on the high ridge near Sanders’ hill, and Giltner was pushed back to the bluffs

along the Holston River. The 10th KY Cavalry was on the bluff at the ford, with the 10th KY Mounted Rifles to their left.

The 64th VA Reserves were then to the left of that regiment, and the 4th KY was to the left of them. Finally, on the extreme

end of the line was Lt. Col. Preston’s 300 reserves. Another battalion of reserves under Lt. Col. Smith and

Major John S. Prather were barricaded around Governor Sanders' home. The Federal forces advanced on the Confederate line.

At midmorning, the Union forces formed into three columns and attacked the reserves surrounding Sanders’ house. The

13th Battalion of Virginia Reserves stationed at the house fought, but the Union forces were able to push them back to Chestnut

Ridge. The Union troops stormed the yard, and followed the reserves up Chestnut Ridge, where they were met by the Confederate

brigades of Gen. Robertson and Colonel George Dibrell.

The three Union columns then moved to attack Trimble’s position at

the ford. One column went directly down Sanders’ hill, another moved along the river, and one swept across the wide

bottom of the hill. The Federal forces crossed the ford, scaled the opposite cliff and attacked Trimble’s position.

In response, the 10th Kentucky Mounted rifles and the 64th Virginia were sent to support Trimble. Giltner went to the reserves

barricaded in trenches at the nearby church and moved them down the road and up by Elizabeth Cemetery to support Trimble.

Trimble fell back, and the colonel himself was killed. The Federal column

led by Colonel Hanson was on the far left side of the mountain. His brigade eventually met up with the 4th Kentucky and Preston’s

reserves.

The Union forces were then repulsed on all sides, and the colored contingent

was severely crippled after it made a series of determined charges against the Confederate right. Unlike the white Union

units sporting Spencer carbines, capable of firing 7 shots from a tube and enjoying a sustained

rate-of-fire of 21 rounds per minute, the black soldiers were given single-shot, muzzle-loading Enfields, which, upon being discharged

while on the exposed embankment, were absolutely worthless.

Burbridge, becoming more frustrated with the lack of progress,

decided an all or nothing gamble by pushing his entire IV Brigade against the stubborn Confederate right. Having

nearly exhausted their ammunition, the 5th US Colored Cavalry, consisting of 400 recruits, with the 11th Michigan and

12th Ohio cavalries, under the brigade commander, Col. Robert W. Ratliff, began their steady ascent up the steep

terrain while enemy fire poured down into their exposed position. The raw recruits of the 5th, with their Enfields, had

made two heroic charges up the mountainside toward Chestnut Ridge, only to be raked by grape and canister shot

and then crash into Confederate musketry and be driven back with heavy losses.

The Spencer carbine, a shorter version of the Spencer repeating rifle, was a manually operated

lever-action, repeating rifle fed from a tube magazine that held seven cartridges, which allowed the experienced horseman

a rate of fire of 14 to 21 rounds per minute. The Enfield was designed to fire while in line, in formation, not for charging

up the side of a mountain while the enemy is entrenched on good ground pouring hot lead at you. The Spencer

carbine was an outstanding firearm, enabling merely a handful of soldiers the capability of unleashing hell at the enemy.

It was also designed for cavalrymen, allowing the 7-round tube to be exchanged for a loaded one for rapid firing while

on horseback. On a mountain side, the carbine was king.

The 5th resembled a slow wave

rolling across the terrain as it made the third and final attempt to take the Confederate works on Chestnut

Ridge. With colored troops now falling dead and wounded from enemy small arms fire, the soldiers, waiting patiently

to fire their single-shot weapons, continued to press slowly toward the objective and upon discharging their Enfields

at some 50 yards distance from the well-entrenched Rebel works, the fighting 5th let out a shout and rushed

forward. They struggled to move up the steep incline and into the Confederate outer works, consisting of rifle pits with head

logs, where they engaged in some hotly contested hand-to-hand combat, and with sheer numbers they overran the works

and pushed the enemy toward the ridge. But without ammunition and any reserves to reinforce their move, they were forced back

with many of them left wounded and dying on the field. Having pulled back to the outer

trench, the bloodied 5th readied itself for what it believed would be an imminent countercharge — only it would never

occur. Ratliff’s Brigade was running perilously low on ammunition and was cut off from the rest of Burbridge’s

forces and their supply line.

Active firing ceased around 5 in the evening, and at that point the

Confederates were able to hold the mountain pass at Hayter’s Gap, which was the most direct route out of Saltville.

The Union troops continued to hold their position one mile out of Saltville until

nightfall. Generals John Breckinridge and John Echols arrived after nightfall, with the small brigades of Generals Basil

Duke, George Cosby and John C. Vaughn. According to the memoirs of Gen. Duke, Vaughn was left at Carter’s Station,

Tennessee, while Cosby and he were ordered by Echols to head on to Bristol, TN., on September 30th. However,

the following day, they received word from Gen. Echols that they were to head to Saltville, and arrived shortly after their

own brigades. With the “fresh” brigades, the Confederates were reinforced, and intended upon resuming the offensive

in the morning.

Col. Brisbin reported moving 400 of

the 5th USCC into action, a number that Mosgrove later noted as participating in the fight during that day. That evening,

Gen. Dibrell told Mosgrove that his men had fought 2500 Yankees during the battle, and had taken down 200 of those men. After

dark, Captain Guerrant and Mosgrove also met up with Gen. Robertson, who claimed that his men had, “killed nearly all

the negroes.” His claim was inaccurate of course, but with scores of colored troops strewn across the field on

the Confederate right, he may have initially thought that the entire 5th had indeed been nearly wiped out. At the close

of the evening, the 4th Kentucky relieved Trimble’s battalion of guarding the ford between the Confederate and Union

camps.

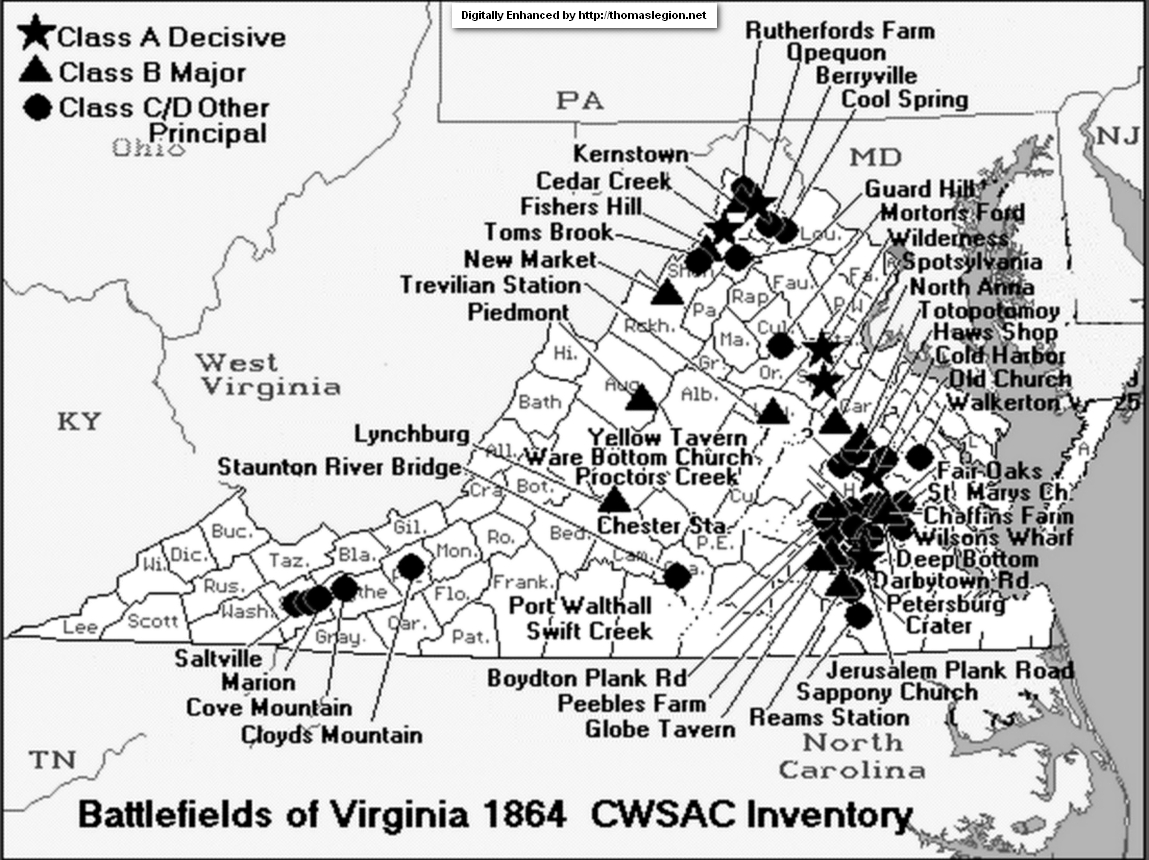

| Map of Virginia Civil War Battles in 1864 |

|

| (Map) Battle of Saltville, Virginia |

Retreat: Monday, October 3rd began with a Federal

retreat ordered by Burbridge early in the morning, still during the dark, but it was not the kind of withdrawal the Union

commander would report to headquarters on Oct. 7th: "In the evening our ammunition gave

out, and holding the position taken until night, I withdrew the command in excellent order and spirits."

It was nothing short of a rout with the Federals retreating in confusion

and abandoning from carbines to more than 100 wounded left for dead. The murdering of any reportable number of black troops

and white officers could only occur if the Union army left them during a hasty

retreat. So contrary to Burbridge writing in his official report that it was an orderly and excellent withdrawal, it

was every man for himself during the exodus of Saltville. Ammunition was exhausted, the Union army had pressed itself into a

grinder, Confederate reinforcements had arrived, and Burbridge left under the

cover of darkness to save his weary command from further disaster. While the defeat at Saltville was due to the poor

planning and tactics of Burbridge, it was the chaotic retreat that would force the battle of salt into public spotlight. Instead

of eyeing Burbridge for the debacle, Northerners would demand vengeance on those who had committed the murders of the

defenseless black and white men on that day.

We whipped the enemy badly here, recorded

Confederate Brig. Gen. John S. Williams on the activity at Saltville, and the Yankees retired in confusion, leaving their

dead and wounded in our hands. Their negro troops were also cut up, continued Williams.

The Union troops abandoned their position

without taking much of their equipment, and even leaving many of the wounded behind on the field in order to gain ground

on the expected Confederate pursuit. As the morning sun strained to pierce the foggy and smoke filled sky looming over the

battlefield, Gen. Breckinridge ordered a scout to locate the Union forces. Captain R.O. Gaithright was sent to pursue

the Federals from the rear, while Gen. Williams was sent with the brigades of Duke, Cosby and Vaughn down through Hayter’s

Gap to intercept the Union at Richlands. Colonel Giltner’s brigade was also sent in pursuit of the Union troops, but

was instructed not to follow too close to allow Gen. Williams enough time to advance beyond the Union movements.

Evidence of the Federal retreat was seen all along the route toward Laurel

Gap. Captain Gaithright eventually caught up with some of the African-American troops near Laurel Gap. Late in the afternoon,

Captain Gaithright also spotted the rear of the Federal column crossing Clinch Mountain. By dusk, Colonel George Diamond with

the 10th Kentucky cavalry attacked the Federal rear while crossing the Clinch River. Duke wrote that he and Gen. Cosby

did overtake Burbridge at Hayter’s Gap; however, mistakes in reconnaissance and other tactical errors allowed the Union

escape. Thus, by noon the following day, it became obvious that Gen. Williams had been unable to head off the Union retreat,

due to their head start. The pursuit therefore ended and the first battle for Saltville was over.

| Battle of Saltville, Virginia, Map |

|

| What was the purpose of salt during the Civil War? Life. |

Union Forces

Union Army Order of Battle

Brevet Maj. Gen. Stephen G. Burbridge

Brig. Gen. Edward H. Hobson

• 13th Kentucky Cavalry

•

30th Kentucky Mounted Infantry

• 35th Kentucky Mounted Infantry

• 40th Kentucky Mounted Infantry

•

45th Kentucky Mounted Infantry

Col. Charles Hanson (wounded), Col. Clinton True

• 11th Kentucky

Cavalry

• 26th Kentucky Mounted Infantry

• 37th Kentucky Mounted Infantry

• 39th Kentucky Mounted Infantry

Col. Robert W. Ratliff

• 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry (with parts

of the 6th U.S. Colored Cavalry)

• 11th Michigan Cavalry

• 12th Ohio Cavalry

Confederate Forces

Confederate Army Order of Battle

Brig. Gen. John Echols; Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge

Department of Southwest Virginia

Brig. Gen. Alfred E. Jackson

Col. Henry Giltner

• 4th Kentucky Cavalry

• 10th Kentucky

Cavalry Battalion

• 10th Kentucky Mounted Rifles

• 64th Virginia Mounted Rifles

• Two Independent

Companies of Kentucky Cavalry under Captain Barton W. Jenkins and Captain T. W. Barrett

Lt. Col. Robert T. Preston

• 4th (5th) Virginia Reserve Battalion

Lt. Col. Robert Smith

• 13th (6th) Virginia Reserve Battalion

Captain John W. Barr

• Virginia Artillery Battery

Army of Tennessee

Brig. Gen. John S. Williams

Col. William C. P. Breckinridge

• 1st Kentucky Cavalry (one

battalion)

• 9th Kentucky Cavalry

Col. George G. Dibrell

• 4th Tennessee Cavalry

• 8th

Tennessee Cavalry / 13th Tennessee Cavalry

• 9th Tennessee Cavalry

Brig. Gen. Felix H. Robertson

• 3rd Confederate Cavalry (fragment)

•

6th Confederate Cavalry (fragment)

• 8th Confederate Cavalry (one battalion)

• 10th Confederate Cavalry

•

5th Georgia Cavalry (fragment)

• Champ Ferguson's Independent Kentucky and Tennessee Cavalry

| Battle of Saltville Interpretive Marker |

|

| First Battle of Saltville, known locally as Battle of Cedar Branch |

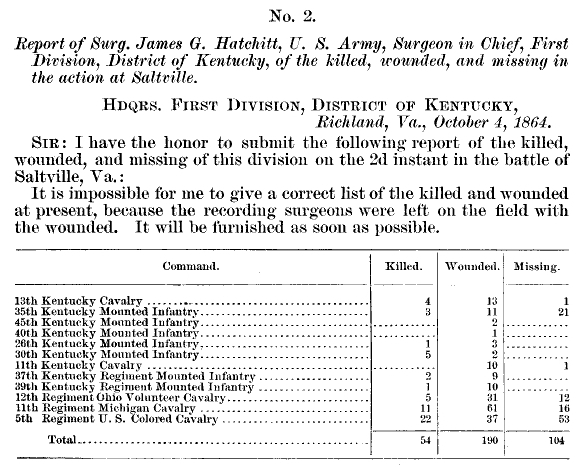

| Battle of Saltville Official Report |

|

| Union Units and Casualties at Battle of Saltville |

Casualties: Cavalry,

unlike the Kentucky mounted units which fought while dismounted at Saltville, were expected to ride and

fight, so to equip even the best crack-shot cavalrymen with muskets was a suicidal endeavor — and the Union

command during the Battle of Saltville knew it. In fairness to the Union Army, it had equipped all its cavalry

units with carbines by 1864, but the 5th was not an organized unit until Oct. 24, 1864. The commander of the 5th, Col.

Brisbin, never complained about using the recruits with Enfields, but with enthusiasm he ordered them forward into

battle.

While the raw and inappropriately armed 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry, would

be ordered to fight while dismounted, they charged headlong into strong Confederate works, then fired their single-shot P53

Enfield muskets, and unable to reload they were mowed down by the experienced foe similar to a sharp sickle slicing through grass.

(Right) Union units and casualties suffered at Battle of Saltville. This

casualty report was compiled by the division's chief surgeon, and it concurs with casualty reports submitted by Brevet Maj.

Gen. Burbridge himself.

The 5th US Colored Cavalry lost 28% of the force it fielded and it suffered 33% of the total Union casualties

at Saltville.

In his after battle reports on Oct. 7 and 10, 1864, Gen. Burbridge stated his losses at 350. Confederate

casualties were stated "as fewer than 100." On Oct. 4, Surgeon James G. Hatchitt, Chief Surgeon, First Division,

District of Kentucky, submitted his casualty report for the respective units involved

in the fight at Saltville. Although Hatchitt stated that the report was not complete because surgeons were still in the field

with the wounded, the numbers would only change as surgeons marked and moved any wounded who died to the killed

category. Hatchitt shows 348 total casualties, with 54 killed, 190 wounded, and 104 missing. His casualty report

includes 112 losses for the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry: 22 killed, 37 wounded, and 53 missing. Colonel James S. Brisbin,

commanding 5th USCC, wrote in his report, Oct. 20, 1864, that "Out of the 400 engaged 114 men and 4 officers fell killed

or wounded." Brisbin had actually included missing-in-action, wounded, and killed in a simple total for his report, but

Hatchitt, who oversaw attending surgeons in the field, presented categorical losses for the unit.

Captain Guerrant also discussed

the incident in his diary. He noted that he heard the continuous sound of rifle fire which meant the death of, “many

a poor negro who was unfortunate enough not to be killed yesterday.” He wrote that his men did not take any Negro

prisoners, and that great numbers of the African-American soldiers were killed. However, he did not specify any

number of soldiers killed. According to first hand accounts from soldiers of both armies, although no exact count

was given, the total number of black soldiers murdered was less than 50.

On October 3rd, Mosgrove wrote that Colonel Hanson of the Federal army was lying wounded in a field hospital,

having been shot by a minie ball; he was drunk and swearing at the hospital staff. This same hospital is where Mosgrove writes

that while surgeon William H. Gardner was tending the Federal wounded, three armed Confederate soldiers stormed into the hospital

and fatally wounded five African-American soldiers. Mosgrove claims to have witnessed a great deal of slaughtering of

members of the USCC on the fields, primarily by two Tennessee brigades under the command of Gen. Robertson and Colonel Dibrell.

However, Mosgrove never specifies the total number of black soldiers killed during the massacre.

This

battle involved fighting in and around Saltville and also was a running fight while the Union force was retreating.

With the exception of two cavalry regiments, 11th Michigan and 12th Ohio, the Union army consisted of

Kentucky mounted units. The battle included Confederate regulars, reserves, militia, and even guerrillas, which

complicated an exact casualty count, too. The Confederate strength varied during the battle because of the types

of units, such as guerrilla units, which would strike the Union army in and around Saltville and then vacate the area, only

to reappear and unleash subsequent blows. While units were engaged, Confederate troops were still arriving from neighboring East

Tennessee.

| Bullets used by both armies at First Saltville |

|

| Weapons used by Union and Confederate armies at First Battle of Saltville |

The total losses for the Union command were frustrated for other reasons:

the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry was green, it was a raw unit from Kentucky that had been thrown together en

route to Saltville. Whereas some men of the unit had yet to enlist, the 5th USCC was not an official Union unit

until it was organized on October 24, which was three weeks after the battle. High casualties for the colored troopers

can partially be attributed to their being inexperienced, but the brunt of the blame must be shouldered by the Union

military for arming the black cavalrymen with Enfield rifle-muskets, while its experienced white cavalry marched

into the fray sporting Spencer carbines capable of firing 14 to 21 rounds per minute. The Enfield had

to be reloaded through the muzzle after each shot, meaning dismounted of course. It also had a lengthy reloading

process that enabled (or restricted) an experienced foot soldier to fire three aimed shots per minute. Once the

black troops fired their single-shot Enfields in the action, they were exposed on the side of the mountain and became easy

targets for the Confederates shooting down from the rifle pits.

Carbines and rapid

firing rifles were adopted by the Union Army for all cavalry units early in the Civil War, unless you were a member of the

5th USCC during the First Battle of Saltville in 1864. Most of the cavalrymen, with the exception of the colored cavalry of

course, also had two or three revolvers at Saltville, which was standard practice by both Union and Confederate cavalries

by 1864. Another disparity, not that it would have made a difference to the untrained colored cavalry or any cavalryman, that

day, was the fact that while the single-shot muzzle-loading Enfield had an effective range of 300 plus yards,

the Spencer repeating rifle could reach out and touch the enemy at an effective range of more than 500 yards, but the Spencer

carbine, because of its shorter barrel, had an effective range of 150-200 yards. (See also Civil War Weapons, Small Arms, Firearms,

and Edged Weapons and Civil War Weapons, Firearms, and Small Arms,)

Analysis: The Battle of Saltville began around 11 a.m., Sunday, October 2, and lasted until 5

p.m. Arriving just earlier that morning at 9:30 with 1,700 men, Confederate Brig. Gen. John S. Williams commanded Saltville's

2,800 defenders during the fight. Williams and the other Southern field commanders handled their troops well for the six hours

of the battle; conversely, Burbridge led his troops rather poorly. The Confederates commanded the heights and did terrible

damage with their long-range Enfields firing downhill at the struggling Federals (Davis, 1971). Davis (1971, p. 11) describes

an almost mirthful attitude among the Southerners, some shouting after a volley "Come right up and draw your salt." One soldier,

after firing at a bluecoat, yelled "How's that? Am I shooting too high or too low?" By 5 p.m., Burbridge knew he was beaten

and withdrew. Thanks to their excellent defensive positions, the Confederates lost fewer than a hundred killed and wounded;

Burbridge reported a total of 350, most of them left behind on the field (Davis, 1971). The Battle of Saltville was a clear

Southern victory that kept the saltworks safe for another few months. As Davis (1971, p. 48) points out, it could have led

to more significant things but the Confederacy was too weak to exploit the victory. One historical note of great interest

to Civil War scholars concerning this engagement is the intensely debated "Saltville Massacre" (Davis, 1993). According to

some (Davis, 1971), rebel soldiers, after the battle, shot many wounded Union troops, especially African-Americans, lying

helpless on the battlefield; other Federals were murdered some days later in the Confederate hospital set up at nearby Emory

and Henry College. Marvel (1991, 1992) vigorously disputes this and refers to the alleged massacre as a "legend." The interested

reader is directed to these sources for detailed accounts.

Although General Sun Tzu lived more than two millennia ago, his Chinese military treatise, The Art of

War, continues to influence military minds the world over. Tzu says that "Strategy without tactics

is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat."

The principles of Sun Tzu's The Art of War are currently taught at elite schools such

as West Point, Navy Academy, US Army War College, and Air Force Academy. While both sides at

Saltville failed to fully implement Tzu's principles, Burbridge made numerous crucial mistakes that led to his defeat.

To paraphrase Sun Tzu, when you have the advantage press it, but Burbridge rested his large army the day before and just some

miles prior to the 400 Confederates that awaited him, thus allowing the enemy precious time needed to swell his ranks

to 2,800 on the high ground.

Tzu states that you should not attack an enemy at his strongpoint; don't attack when and where your

enemy expects it; and never press the fight when you are low on supplies. Burbridge committed all these mistakes. The

Confederate leadership, mainly Williams, according to Tzu, applied many of The Art of War principles by first

hitting the enemy when and where he least expects it, meaning East Tennessee; by delaying the enemy and enlarging

his force for the imminent fight; by allowing the enemy to believe that the army remains smaller; and by applying

treacherous terrain to an advantage and then luring the opponent into attacking. While Breckinridge failed on the next

tactic, Burbridge succeeded, however. To completely destroy your enemy you must eliminate his route of escape.

Brig. Gen. John S. Williams

summed up the fight in one sentence: "We whipped the enemy badly." Although a decisive Confederate victory,

Union forces would subdue the saltworks in two months on December 21, 1864, during the Second Battle of Saltville.

Of note was the raw, untrained 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry that was thrown together en route to the First Battle of Saltville.

The 5th USCC had its ranks filled with men who had not yet enlisted, and while the 5th

fought heroically, it would not be an official unit until three weeks after the battle when it formed on October

24, 1864. The men of the 5th USCC, numbering 400 effectives at Saltville,

fought on par with any white soldier, according to several battle reports from Union officers.

The Union assault up a steep hill and directly into the stout Confederate

front was suicidal, and without sufficient reserves, Burbridge would force the action only to blame others for his failure

to achieve a victory. The Union general was quick to take credit for his past victories, but at Saltville he had many

excuses for the debacle, some rather outlandish. Burbridge would give a myriad of excuse for his failed attempt at Saltville,

hoping that at least some of them would stick.

Bvt. Maj. Gen. Burbridge opened his report to headquarters by stating that he had whipped the Rebels

in every engagement in Virginia. He said that the only thing that prevented him from

entering the works was lack of ammunition, but then said the failure was also because Gen. Gillem did not come

to his aid. He wrote that he could only put into action 2,500 men, but that the enemy greatly outnumbered him by placing

as many as 10,000 on the field, or that he could have taken the works. Our loss was 350, but it is certain the enemy

lost many more, continued Burbridge.

His following statement in the Official Records was false. We held the works for hours, said Burbridge,

but I withdrew the command in excellent order and spirits, and nearly all the wounded colored soldiers were brought off the

mountain. If that was the case, then the more than 200 wounded and missing left on the field, many African-Americans, would

not have fallen into the hands of an angry enemy that would later be accused of murdering many of them.

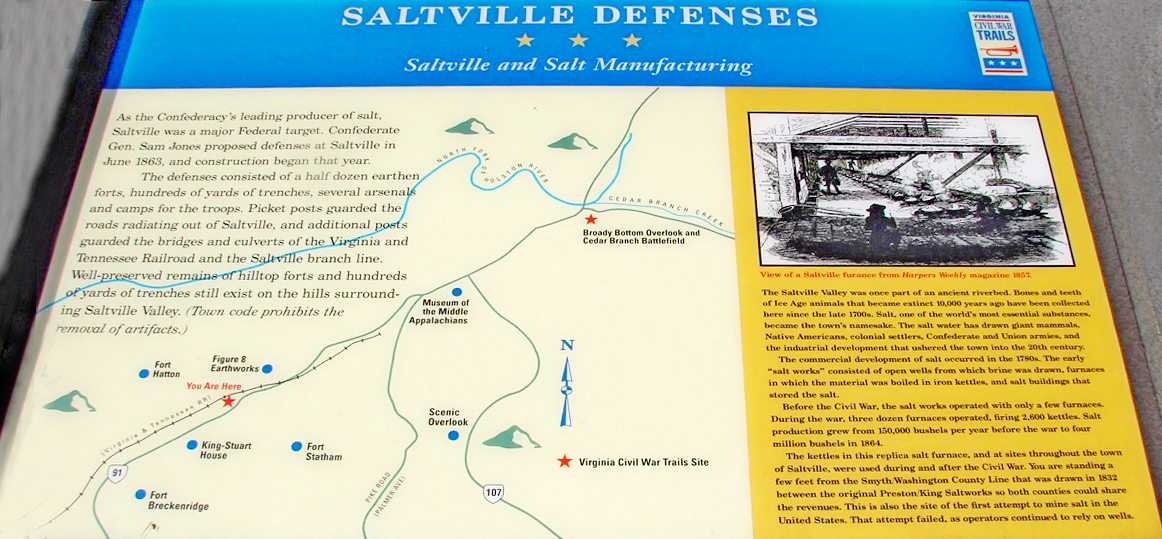

| Saltville, Virginia, Civil War |

|

| Ring of Defenses at Saltville |

|

| Saltville shaded in red |

Saltville: Salt

played a major role during the Civil War. Salt not only preserved food in the days before refrigeration, but was also vital

in the curing of leather. Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman once said that "salt is eminently contraband," as an

army that has salt can adequately feed its men.

The most important saltworks of the Confederacy made Saltville,

Virginia, contested real estate for both armies. In 1864, the works manufactured about 4,000,000 bushels (200,000,000

pounds) of salt, roughly one-third of the said mineral required by the Confederacy. In the same year, the Union army

twice advanced to capture and lay waste to the saltworks, as it was the last prominent source of salt for most of

the Confederate states. The First Battle of Saltville, October 1864, saw the Confederates repulse the disorganized Union

attack led by Bvt. Maj. Gen. Burbridge, but a few months later during the Second Action of Saltville in December, Federal

forces under Maj. Gen. Stoneman would lay waste to much of the vital works. Two months later in February, however, the

saltworks were at near full production for the Confederacy, but for want of tracks in the area, trains were unable

to haul the capacity needed to sustain a viable fighting force in the field.

In Georgia, the price of salt depended on one's family circumstances. Heads

of families could purchase a half-bushel of salt for $2.50. If a widow had a son in the Confederate army, the price was only

$1.00. But if the widow's husband served his nation, the price was free. Local court clerks sent the salt requests to the

state government, which in turn allotted the salt to the counties as requested.

Some scholars contend that Florida's greatest contribution to the Confederate

war effort was in producing salt. With a total investment of $10 million, Floridian salt plants worked 24 hours a day boiling

salt from sea water, mostly in the area between Saint Andrews Bay and St. Marks, Florida. Occasionally, Union forces came

ashore just to destroy the boilers. Confederate law made those involved in salt-making immune to being drafted, making it

a popular profession in war-time Florida; the estimated total workers involved was 5,000.

One way Southern families acquired salt was to boil the dirt in areas where

they had previously cured meats. They would dig it out, and strain it.

Avery Island, off the Louisiana coast, gave the Confederacy a huge supply

of rock salt until the Union captured it. However, Confederates never realized that similar structures to the rock salt mine

were all along the Louisiana and Texas coasts of the Gulf of Mexico, and therefore salt could have been more easily attained

if they had but realized it.

(Sources and related reading are listed below.)

Recommended Reading: Saltville

(VA) (Images of America), by Jeffrey C. Weaver (Author), The Museum of the Middle Appalachians (Author): Description:

Saltville, Virginia, lies on the banks of the North Fork of the Holston River on the border between Smyth and Washington Counties.

Its history began very long ago; in fact, archeological evidence suggests extensive human habitation there for more than 14,000

years. Saltville was named because it was a source of salt,-and by the end of the 18th century, a thriving industry was born.

During the Civil War, Saltville attained considerable importance to the Confederate government as a supply of salt. Continued

below…

A large Confederate

army garrison was maintained there, and extensive fortifications were constructed. After the Civil War, the town led the way

in industrialization of the South. Flip through the pages of Images of America: Saltville to learn why Saltville is one of

the most historic places in the world. About the Author: The Museum of the Middle Appalachians, located on Palmer Avenue

in Saltville, was established by the Saltville Foundation in the 1990s. It has become the repository for fossils, artifacts,

and photographs of the region. Author Jeffrey C. Weaver holds degrees in American history from Appalachian State University,

and after serving in the U.S. Army for several years, he worked as a contracting officer for the U.S. Department of Energy.

He is currently the manager of the Chilhowie Public Library.

Recommended

Reading: Saltville Massacre (Civil War Campaigns

and Commanders). Description: In October 1864, in the mountains of southwest Virginia,

one of the most brutal acts of the Civil War occurs. Brig. Gen. Stephen Burbridge launches a raid to capture Saltville. Included

among his forces is the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry. Repeated Federal attacks are repulsed by Confederate forces under the command

of Gen. John S. Williams. Continued below…

As the sun

begins to set, Burbridge pulls his troops from the field, leaving many wounded. In the morning, Confederate troops, including

a company of ruffians under the command of Captain Champ Ferguson, advance over the battleground seeking out and killing the

wounded black soldiers. What starts as a small but intense mountain battle degenerates into a no-quarter, racial massacre.

A detailed account from eyewitness reports of the most blatant battlefield atrocity of the war.

Recommended

Reading: Lee's Endangered Left: The Civil War In Western Virginia, Spring Of 1864. From Kirkus Reviews: A competent, well-executed addition to the

ever-growing horde of Civil War literature, by Duncan (History/Georgetown University). The author reconsiders Union General

Ulysses S. Grants attempts to destroy the Confederates, led by General Robert E. Lee, at their traditional stronghold in western

Virginia and his efforts to threaten Lynchburg

during the spring and summer of 1864. Continued below…

The writing

here is crisp; refreshingly, our chronicler pays sharp attention to the effects of the campaign on civilians as the Union

army penetrated beyond its supply lines and came to live off the countryside in one of the Confederacy’s richest agricultural

regions, bringing home the harsh realities of war to civilians. The campaign swung back and forth, with Northern victories

at Cloyd's Mountain and New

River Bridge and Confederate routs at New Market, followed by a Union

failure to seize Lynchburg. Though the campaign proved costly

to the South, overall the Unions hope to capture the Shenandoah Valley foundered and the Confederates then went on to threaten

Washington, D.C. Duncan sensitively employs a wide variety of sources, military and civilian, to add to the coherence of his

account. Still, the books scope remains narrow, focusing on a not terribly glamorous period in the wars history; then, too,

wed do well to have the volume trimmed by a third. Duncan’s contention that the Unions

severity in dealing with civilian populations was directly reciprocated when the Confederates took Chambersburg,

Penn., creating a chain of vengeance that culminated when Sherman marched through the South, is insightfully argued, offering a fresh analysis to the

historical debate. Casual readers of the Civil War genre (and many die-hard buffs, as well) may want to leave this superbly

researched yet ultimately too specialized study for the historians to ponder. Includes 20 photographs.

Recommended

Reading: Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign,

Spring 1862. Description: The Valley Campaign

conducted by Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson has long fascinated those interested in the American Civil War as well

as general students of military history, all of whom still question exactly what Jackson

did in the Shenandoah in 1862 and how he did it. Since Robert G. Tanner answered many questions in the first edition of Stonewall

in the Valley in 1976, he has continued to research the campaign. This edition offers new insights on the most significant

moments of Stonewall's Shenandoah triumph. Continued below…

About the Author:

Robert G. Tanner is a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute. Tanner is a native of Southern California, he now lives

and practices law in Atlanta, Georgia. He has studied and lectured

on the Shenandoah Valley Campaign for more than twenty-five years.

Recommended

Reading: Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign, by Peter Cozzens (Civil War America) (Hardcover). Description: In the spring of 1862, Federal troops under

the command of General George B. McClellan launched what was to be a coordinated, two-pronged attack on Richmond in the hope of taking the Confederate capital and bringing a quick end to the Civil

War. The Confederate high command tasked Stonewall Jackson with diverting critical Union resources from this drive, a mission

Jackson fulfilled by repeatedly defeating much larger enemy forces. His victories elevated him to near iconic status in both

the North and the South and signaled a long war ahead. One of the most intriguing and storied episodes of the Civil War, the

Valley Campaign has heretofore only been related from the Confederate point of view. Continued below…

With Shenandoah

1862, Peter Cozzens dramatically and conclusively corrects this shortcoming, giving equal attention to both Union and Confederate perspectives.

Based on a multitude of primary sources, Cozzens's groundbreaking work offers new interpretations of the campaign and the

reasons for Jackson's success. Cozzens also demonstrates instances

in which the mythology that has come to shroud the campaign has masked errors on Jackson's

part. In addition, Shenandoah 1862 provides the first detailed appraisal of Union leadership in the Valley Campaign, with

some surprising conclusions. Moving seamlessly between tactical details and analysis of strategic significance, Cozzens presents

the first balanced, comprehensive account of a campaign that has long been romanticized but never fully understood. Includes

13 illustrations and 13 maps. About the Author: Peter Cozzens is an independent scholar and Foreign Service officer with the

U.S. Department of State. He is author or editor of nine highly acclaimed Civil War books, including The Darkest Days of the

War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth (from the University

of North Carolina Press).

Recommended

Reading: Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Description: Jubal A. Early’s disastrous battles in the Shenandoah Valley

ultimately resulted in his ignominious dismissal. But Early’s lesser-known summer campaign of 1864, between his raid

on Washington and Phil Sheridan’s renowned fall campaign, had a significant impact on the political and military landscape

of the time. By focusing on military tactics and battle history in uncovering the facts and events of these little-understood

battles, Scott C. Patchan offers a new perspective on Early’s contributions to the Confederate war effort—and

to Union battle plans and politicking. Patchan details the previously unexplored battles at Rutherford’s Farm and Kernstown

(a pinnacle of Confederate operations in the Shenandoah Valley) and examines the campaign’s

influence on President Lincoln’s reelection efforts. Continued below…

He also provides

insights into the personalities, careers, and roles in Shenandoah of Confederate General John C. Breckinridge, Union general

George Crook, and Union colonel James A. Mulligan, with his “fighting Irish” brigade from Chicago.

Finally, Patchan reconsiders the ever-colorful and controversial Early himself, whose importance in the Confederate military

pantheon this book at last makes clear. About the Author: Scott C. Patchan, a Civil War battlefield guide and historian, is

the author of Forgotten Fury: The Battle of Piedmont, Virginia, and a consultant and contributing writer for Shenandoah, 1862.

Review

"The author's

descriptions of the battles are very detailed, full or regimental level actions, and individual incidents. He bases the accounts

on commendable research in manuscript collections, newspapers, published memoirs and regimental histories, and secondary works.

The words of the participants, quoted often by the author, give the narrative an immediacy. . . . A very creditable account

of a neglected period."-Jeffry D. Wert, Civil War News (Jeffry D. Wert Civil War News 20070914)

"[Shenandoah

Summer] contains excellent diagrams and maps of every battle and is recommended reading for those who have a passion for books

on the Civil War."-Waterline (Waterline 20070831)

"The narrative

is interesting and readable, with chapters of a digestible length covering many of the battles of the campaign."-Curled Up

With a Good Book (Curled Up With a Good Book 20060815)

"Shenandoah

Summer provides readers with detailed combat action, colorful character portrayals, and sound strategic analysis. Patchan''s

book succeeds in reminding readers that there is still plenty to write about when it comes to the American Civil War."-John

Deppen, Blue & Grey Magazine (John Deppen Blue & Grey Magazine 20060508)

"Scott C. Patchan

has solidified his position as the leading authority of the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign with his outstanding campaign

study, Shenandoah Summer. Mr. Patchan not only unearths this vital portion of the campaign, he has brought it back to life

with a crisp and suspenseful narrative. His impeccable scholarship, confident analyses, spellbinding battle scenes, and wonderful

character portraits will captivate even the most demanding readers. Shenandoah Summer is a must read for the Civil War aficionado

as well as for students and scholars of American military history."-Gary Ecelbarger, author of "We Are in for It!": The First

Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862 (Gary Ecelbarger 20060903)

"Scott Patchan

has given us a definitive account of the 1864 Valley Campaign. In clear prose and vivid detail, he weaves a spellbinding narrative

that bristles with detail but never loses sight of the big picture. This is a campaign narrative of the first order."-Gordon

C. Rhea, author of The Battle of the Wilderness: May 5-6, 1864 (Gordon C. Rhea )

"[Scott Patchan]

is a `boots-on-the-ground' historian, who works not just in archives but also in the sun and the rain and tall grass. Patchan's

mastery of the topography and the battlefields of the Valley is what sets him apart and, together with his deep research,

gives his analysis of the campaign an unimpeachable authority."-William J. Miller, author of Mapping for Stonewall and Great

Maps of the Civil War (William J. Miller)

Sources: National Park Service; Official Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies; Library of Congress; National Archives; Jonathan Sutherland. African Americans at War: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1;

Blue & Gray Magazine, Volumes 17-18. Blue & Gray Enterprises,

1999; Scott C. Patchan. Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign, 2009;

Richard R. Duncan. Lee's Endangered Left: The Civil War In Western Virginia, Spring Of 1864 (Hardcover), 1999; Thomas D. Mays.

Saltville Massacre, 1998; Jeffrey C. Weaver. Saltville (VA) (Images of America), 2006; Bryan S. Bush. Butcher Burbridge: Union

General Stephen Burbridge and His Reign of Terror Over Kentucky, 2008; Graham MacGregor. Salt, Diet and Health. Cambridge

University Press, 1998; Frances Kennedy. The Civil War Battlefield Guide, 1998; David Heidler. Encyclopedia Of The American

Civil War; Angela M. Dautartas, C. Clifford Boyd, Rhett B. Herman, Robert C. Whisonant. Battles of Saltville: October 2nd,

1864 and December 20th, 1864 (2005); Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy, dmme.virginia.gov; Missouri University

of Science and Technology, mst.edu; Oakland City University, oak.edu.

|