|

Battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi

Civil War Siege of Vicksburg History

Battle

of Vicksburg

Vicksburg

and the Civil War

Other Names: Second Battle of Vicksburg; Second

Vicksburg Campaign; Siege of Vicksburg; Operations Against Vicksburg; Vicksburg Campaign; Grant's Operations Against

Vicksburg

Location: Warren County, Mississippi

Campaign: Grant’s Operations Against Vicksburg (1863)

Date(s): May 18-July 4,

1863, Siege of Vicksburg (47 Days); March 29-July 4, 1863, Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg (97 Days)

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant [US]; Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton [CS]

Forces Engaged: Army of the Tennessee, including reinforcements (US 77,000); Army of Vicksburg (CS 33,000)

Estimated Casualties May 18th-July 4th: 8,037 total (US

4,835; CS 3,202)

Estimated Casualties March 29th-July 4th: 19,233 total (US 10,142; CS 9,091)

Result(s): Union victory

Introduction:

Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant and his command of 35,000 soldiers arrived on the coast of Mississippi and then pushed

his Army of the Tennessee inland and through the battlefields of Port Gibson, Raymond, Jackson, Champion Hill, and Big Black

River Bridge. At each location, as Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton moved his Army

of Vicksburg in an attempt to check each Federal advance, it was swept from the field by the much larger Federal force. Routed

at each point, the Confederate force had nearly been destroyed at Big Black River Bridge, but with the bridge burned hastily by

the scattering Rebels, Pemberton's beleaguered army managed to limp back to the trenches and bombproofs of Vicksburg,

but Grant, a relentless soldier, pursued rigorously and soon the Siege of Vicksburg began in earnest. Disagreement over

the defense or abandonment of Vicksburg, the Confederacy's last remaining stronghold on the Mississippi River, would

divide the Confederate forces in the area. While one half under Pemberton, the Army of Vicksburg, would stay at

the fortress city for an Alamo style defense, Gen. Joseph Johnston, commanding the Army of the West, would

remain idle some 30 miles distant with a command that would grow to some 31,000 strong. While in the trenches

and bombproofs of the fortress city above the Mississippi, Pemberton now could field only 18,500 effectives from an aggregate

force that had recently numbered 33,000. For the next six weeks, while pleading daily with Richmond for more troops

before he could press any relief effort, Johnston would remain idle and belay any assistance for the besieged

Confederates at Vicksburg. Grant's army of 35,000, meanwhile, was quickly strengthened to 50,000, followed by additional

reinforcements which increased his readiness to some 77,000 effectives during June, thus making any possibility

of a successful move by Johnston an utter impossibility.

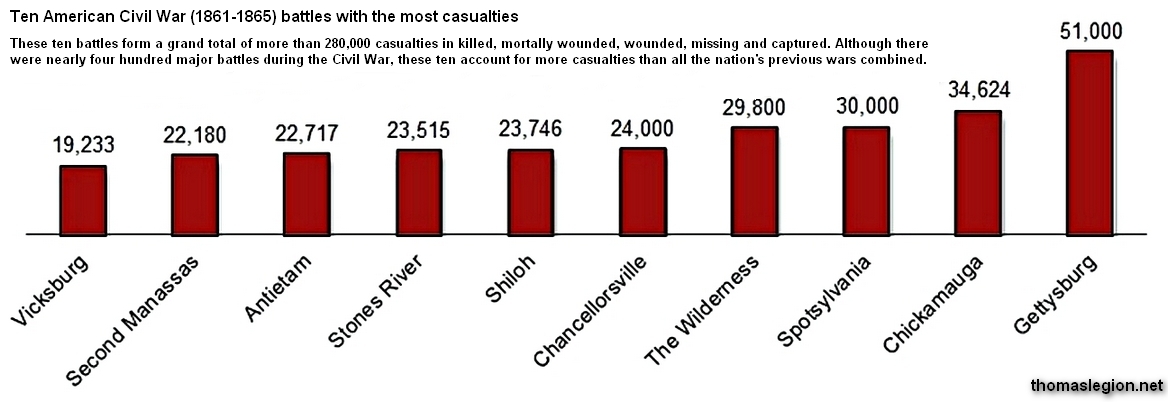

| Total Battle of Vicksburg Casualties |

|

| Battle of Vicksburg Total Killed, Wounded, and Missing |

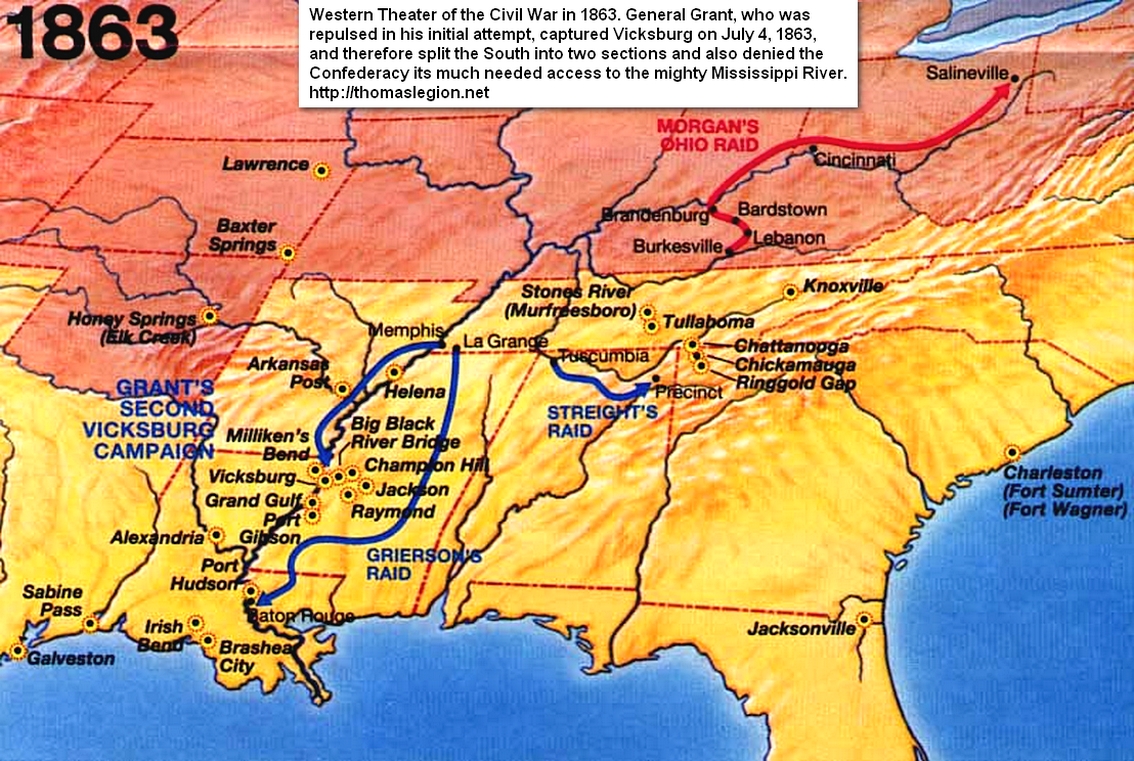

| Battle of Vicksburg Map |

|

| Map showing location of Vicksburg Battlefield |

| Battle of Vicksburg Killed, Wounded, and Captured |

|

| Battle of Vicksburg Casualties, March 29 to July 4, 1863 |

The Confederate

army had pursued and fought the Union command only to be forced off the fields, and while the Rebel force had bloodied

the nose of the enemy, it had reeled and been crippled by chasing and engaging the larger, stronger Yankee contingent.

The Confederates were routed as they pressed the Federals on five battlefields while moving across Mississippi from May

1 to May 18, and as Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, capitulated during the process, Pemberton would move his

demoralized army into its Alamo, the Fortress of Vicksburg, where the tenth highest casualties of the Civil War would

be numbered. Here, for 47-days, while cannonading was exchanged daily between the armies and as 200-pound shells

soared and screamed across the terrain from both land and river batteries, Grant continued to extend his siege lines, tunnel

beneath the Confederate works and detonate a monstrous 2,200-pound mine, and even force hand-to-hand fighting by ordering

two Union assaults against Stockade Redan, May 19 and 22, which only resulted in staggering Federal losses and without one

inch of ground gained.

During the battle

and siege of Vicksburg, the aggressiveness of

Grant and Union determination were pitted against the stubbornness of Pemberton and sheer Southern mettle. The

worst kind of dog to pick a fight with is an injured, starving, miserable, and cornered dog, and that is exactly what

Grant had created as he rolled onto the scene and punished the Confederate army on five battlefields of Mississippi from

May 1 to May 18, and by forcing the injured enemy into the trenches and fieldworks on the bluffs of Vicksburg on the

18th, and then attacking it, would be like holding the rabid dog by the ears, for you didn't want to do it, but you sure didn't

want to let go.

Vicksburg,

being absent any reinforcements, was an utterly doomed city during Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's Siege of Vicksburg, May 18--July

4, 1863, which endured for 47-days. The Union siege of the Mississippi port locale was relentless and accompanied with daily

shelling from both land and river. The city was reduced to large heaps of rubble that emanated the pungent odor of a

modern-day trash dump. The inhabitants had transitioned from palatial mansions to living in some 500 bombproofs, caves

and large holes that had been burrowed in the bluffs and hills that laced the ruins, and were living off the

meat of dogs, mules, and snakes, as well as rats and other vermin that occasionally strayed into the trap. There were

so many caves and holes being occupied by the local citizenry that the Union soldiers referred to Vicksburg as Prairie

Dog Village.

"Vicksburg is so strong by nature and so well fortified that sufficient force cannot be brought

to bear against it to carry it by storm against the present Garrison. It must be taken by a regular siege or by starving out

the Garrison." Letter from Grant to Maj. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut, May 31, 1863

Grant's campaign was "one of the most brilliant in the world," said Lincoln, as Lee meanwhile

was opening the distance between his army and the entire State of Mississippi, because the Virginian had business

in the North at a familiar location named Gettysburg, a small town that would undoubtedly be unknown had it not

been for the 51,000 casualties that fell among its fields in July of 1863. Vicksburg would not receive assistance from Lee,

nor from any other army, because the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia had hoped that by pushing his massive army

into Union territory it would force Grant to abandon the ruinous port place and pursue him, and the other objective in

Pennsylvania was to forage for food and supplies in the abundant Northern fields and warehouses, and therefore grant

a much needed respite to the depleted crops just south of the Mason-Dixon.

In May and June of 1863, Maj.

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s armies converged on Vicksburg , investing the city and entrapping a Confederate army under Lt. Gen. John Pemberton. On July 4, Vicksburg surrendered after

prolonged siege operations. This was the culmination of one of the most brilliant military campaigns of the war. With

the loss of Pemberton’s army and this vital stronghold on the Mississippi, the Confederacy was effectively split in half, therefore fulfilling Gen. Winfield

Scott's Anaconda Plan and further tightening the noose on the Confederacy. Grant's successes in the West boosted

his reputation, leading ultimately to his appointment as General-in-Chief of the Union armies. , investing the city and entrapping a Confederate army under Lt. Gen. John Pemberton. On July 4, Vicksburg surrendered after

prolonged siege operations. This was the culmination of one of the most brilliant military campaigns of the war. With

the loss of Pemberton’s army and this vital stronghold on the Mississippi, the Confederacy was effectively split in half, therefore fulfilling Gen. Winfield

Scott's Anaconda Plan and further tightening the noose on the Confederacy. Grant's successes in the West boosted

his reputation, leading ultimately to his appointment as General-in-Chief of the Union armies.

The Confederate army suffered

3,202 in killed and wounded while Union casualties totaled 4,835 during the 47-day Siege of Vicksburg,

of which 4141, some 85%, of the Union losses occurred on the days of May 19 and 22, respectively. The list

of battles and casualties disclosed on this site for Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg total exactly 10,142

Union losses and 9,091 Confederate casualties, for a grand total of 19,233 casualties, therefore removing the guess work as

to which battles were fought and how many men perished on any given date.

Was it a battle or a siege?

Which dates constitute the Vicksburg Campaign? When was the battle and siege of Vicksburg? There were actually two

principal battles within the siege, such as when Grant moved a portion of his army out of the lines and pressed

the enemy fiercely on both May 19 and 22, which resulted in more than 85% of the Union casualties during the 47-day

siege. While the dates for the Battle of Vicksburg, May 18 to July 4, are generally universally agreed upon, the battles

inclusive of the dates are not, however. Since the battles within the Siege of Vicksburg vary so do the casualty

figures. Whereas the majority of the sources for the killed and wounded vary greatly for the 47-day investment and siege,

most sources seem to agree on the same 97-day timespan for Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg (March 29 to

July 4, 1863) and show the usual Union casualties of 10,142 and Confederate losses of 9,091. For most writers

to reconcile their dates and casualties for all of Grant's Operations, they tally their numbers for the

Siege of Vicksburg (47-days), but only indicate the National Park Service figures and leave it to the reader to imagine which

battles were included and how the respective Union and Confederate casualties were tabulated for the entire 97-days.

| Civil War and Battle of Vicksburg Bluffs |

|

| View of the Mississippi River from the Vicksburg Bluffs |

| Battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi |

|

| Vicksburg Siege Warfare and Life in bombproofs and caves |

| Battle of Vicksburg History |

|

| Union Cannon at Battle of Vicksburg |

On

this site will you receive reliable casualty figures for each battle during the 47-day Siege of

Vicksburg and also the casualty reports for both the Union and Confederate armies by battle, phase,

and operation, and finally the total numbers for all dates specified. An easy to read casualty list is included for quick

reference, which shows the killed, mortally wounded, wounded, missing, and captured for each army and action during the

Battle of Vicksburg and for Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg. Lastly, the final casualty tallies

and grand totals concur with all figures for the battle and operations against Fortress Vicksburg.

Consider the following

questions as you read about the account and capitulation of Vicksburg. How good was Lt. Gen. Grant's generalship? Was Confederate

Lt. Gen. John Pemberton really as inept as we have been led to believe? Which battle of the months-long campaign was decisive

and sealed the fate of the city? Why didn't Gen. Joseph Johnston move his army earlier in an attempt to break the

siege? Did Gen. Robert E. Lee have the authority to reinforce Vicksburg, if so, why didn't he come to the aid

of Vicksburg? How did the civilians deal with the constant bombardment and lack of food and supplies? What were the roles

of infantry, artillery, and cavalry in this critical campaign? How did the capitulation of Vicksburg affect the outcome

of the war? Was there any silver lining for the Confederacy with the loss, such as lessons learned?

| Battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi |

|

| Drawing of siege lines at Vicksburg, Mississippi |

Summary: Whereas Vicksburg was said to be a stronghold that

no army could ever conquer, a determined Ohioan by the name of General U.S. Grant thought otherwise. The Battle

of Vicksburg was a 47-day siege of the city (May 18--July 4, 1863) and was a part of Grant's Operations against

Vicksburg (March 29–July 4, 1863). While the subject is the Battle of Vicksburg, it is important to place

the action in context with its parent Vicksburg Campaign, which was an exhaustive effort to capture the City of Vicksburg,

a fortress city located high on the bluffs of the Mississippi River.

Maj. Gen. U.S. Grant's army of some 35,000 strong would arrive at Vicksburg only to swell its ranks to 77,000

men within weeks. He was opposed by Confederate Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton's army that had been reduced from some 33,000 soldiers

to an effective fighting force of scarcely 18,500.

Fresh from five victories in the field the Union army converged on Vicksburg on May 18, 1863, encircling

and trapping Gen. John Pemberton's force, and after executing two failed assaults resulting in more than

4,000 Union casualties, the aggressive Grant reluctantly settled into a 47-day siege, which would end with the Confederate

surrender on July 4, 1863. Grant attempted the assaults, May 19 and 22, against Stockade Redan, and even detonated a

large mine under the Third Louisiana Redan, in a brutal attempt to break through the strong Confederate fieldworks. The assault

of May 22 was repulsed with 3,200 Union casualties and without the Federals gaining one inch of ground.

The two attacks accounted for more than 85% of the total Union casualties during the siege.

Failing to take the city by storm, Grant settled down to siege operations which consisted of digging approach

and parallel trenches to the main Confederate fortifications in an effort to destroy them by mining operations. The mines

were quite spectacular upon detonation and the subsequent fighting involved hand-to-hand fighting, hand grenades

being lobbed, and a Confederate push with bayonets to crack the stalemate with the determined Federals. The Union

navy was relentless in its cannonading during the siege, too, but while it assisted in the destruction of the palatial

mansions of Vicksburg, its guns had little effect on the more than 500 bombproofs and shelters that had been called home

to the citizens throughout the now ruinous port city.

Gen. Joseph Johnston,

commanding the Army of the West, would say almost daily for six weeks, in McClellan fashion, that he was collecting

more troops before he could press Gen. Grant in an attempt to relieve Gen. Pemberton and the Army of Vicksburg,

who had been forced and pinned down in the trenches of the port city on the bluffs by Grant. Johnston would send

messages to Pemberton from mid-May 1863 to the day that Pemberton surrendered to Grant on July 4, stating that he

was still raising a larger force to come to his aid, but, while Johnston had already massed an army of some 31,000 men, he

would stay beyond the shadow of Grant until Pemberton and his force of nearly 30,000 Confederates had already surrendered.

Johnston, as commanding general, had

refused to even attempt a feint and was therefore culpable for the fall of Vicksburg. Grant, however, had

successfully besieged the Confederate army, and after six weeks in which the soldiers and civilians of Vicksburg had

no food and supplies, and while their morale was lower than the deepest cave in the bluffs, and after enduring relentless daily

cannonading for six weeks, Pemberton reluctantly surrendered the city and his army on July 4, 1863.

During the Battle of Vicksburg, while engaged with Pemberton in the

siege, Grant remained cautious knowing that another Confederate force could press the rear of his army. He therefore

stationed one division in the vicinity of the Big Black River bridge and another reconnoitered as far north as Mechanicsburg,

both to act as a covering force. By June 10, the IX Corps, under Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, was transferred to Grant's command,

enlarging his army to some 77,000 veteran soldiers. This corps became the genesis of the rear guard whose mission was

to prevent Johnston, who was still gathering his forces at Canton, from interfering with the siege. Sherman was given command

by Grant of the command and Brig. Gen. Frederick Steele replaced him at the XV Corps on June 22.

Johnston began slowly moving in the direction of Vicksburg only to halt

his now 31,000 strong command at Big Black River on July 1, but, in what would now have been a difficult

engagement with Sherman who recently assumed command of the additional troops, Johnston stalled in hopes of further enlarging his

army. But it proved to be too late for the soldiers and civilians who had been reduced to eating rats and even shoe leather

in attempts to assuage the hunger pangs.

The commanders Grant and Pemberton would meet under an oak tree midway between

the lines and discuss surrender terms at 3:00 p.m. on July 3, 1863. The next morning, July 4, the Confederate

defenders marched out of their trenches, stacked their arms, and were paroled. After 47 days, the Siege of Vicksburg was over.

| Vicksburg Fortifications |

|

| Vicksburg Battlefield Map. NPS |

| Vicksburg Campaign Map, Support Civil War Trust |

|

| Vicksburg Campaign, aka Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg. Courtesy Civil War Trust, civilwar.org |

| The Civil War Battle of Vicksburg |

|

| Stockade Redan, Vicksburg Battlefield |

| Vicksburg Civil War Battlefield |

|

| What is a redoubt, redan, and lunette? |

(Left) What is a redoubt, redan,

and lunette? A redoubt is an enclosed square or rectangular earthwork with four fronts and four angles. A redan

is a triangular earthwork used to cover points to the rear such as bridges or river fords, and had two fronts and three angles.

A lunette was employed in much the same fashion as a redan, with two faces forming a salient angle, two flanks adjoining

the faces, and the rear open to interior lines. (Right) Stockade Redan was the sight

of the bloodiest fighting during the entire Siege of Vicksburg, and its salient, nearly 20-feet thick in places, was

a well-constructed earthwork that had been built for the fighting to come. Stockade Redan was constructed to protect

the Graveyard Road approach to Vicksburg, and the fortification was given its name because of the wall, or 'stockade,' of

poplar logs built across the Graveyard Road. Grant assaulted the redan twice, May 19 and 22, 1863, only to be repulsed with

heavy casualties. While more than 85% of the total Union casualties for the entire siege occurred on those two days, the Confederate

losses were light. Grant was well-known by the soldiers of both armies for

seizing the initiative and ordering the offensive, but while he would reluctantly settle in for a 47-day siege because

of the more than 4,000 casualties sustained at Stockade Redan, he would

soon direct his miners and sappers to tunnel and then to explode a massive mine under the 3rd Louisiana

Redoubt.

Grant's

Vicksburg Strategy: Grant's strategy, up to the capture of Grand Gulf, had been first to secure a base on the river

below Vicksburg and then to cooperate with Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks in capturing Port Hudson. After this he planned to

move the combined force against Vicksburg. Port Hudson, a Strong point on the Mississippi near Baton Rouge, was garrisoned

by Confederate troops after Farragut's withdrawal the previous summer. At Grand Gulf, Grant learned that Bank's investment

of Port Hudson would be delayed for some time. To follow his original plan would force postponement of the Vicksburg campaign

for at least a month, giving Pemberton invaluable time to organize his defense and receive reinforcements. From this delay

the Union Army could expect the addition of no more than 12,000 men. Grant now came to one of the most remarkable decisions

of his military career.

Information had been received that a new Confederate force was

being raised at Jackson, 45 miles east of Vicksburg. Against the advice of his senior officers, and contrary to orders from

Washington, Grant resolved to cut himself off from his base of supply on the river, march quickly in between the two Confederate

forces, and defeat each separately before they could join against him. Meanwhile, he would subsist his army from the land

through which he marched. The plan was well conceived, for in marching to the northeast toward Edwards Station, on the railroad

midway between Jackson and Vicksburg,

Grant's vulnerable left flank would be protected by the Big

Black River. Moreover, his real objective—Vicksburg or Jackson—would not be revealed immediately and could be

changed to meet events. Upon reaching the railroad, he could also sever Pemberton's communications with Jackson and the East.

It was Grant's belief that, although the Confederate forces would be greater than his own, this advantage would be offset

by their wide dispersal and by the speed and design of his march.

But this calculated risk was accompanied by grave dangers, of

which Grant's lieutenants were acutely aware. It meant placing the Union Army deep in alien country behind the Confederate

Army where the line of retreat could be broken and where the alternative to victory would not only be defeat but complete

destruction. The situation was summed up in Sherman's protest, recorded by Grant, "that I was putting myself in a position

voluntarily which an enemy would be glad to maneuver a year—or a long time—to get me."

The action into which Pemberton was drawn by the Union threat

indicated the keenness of Grant's planning. The Confederate general believed that the farther Grant campaigned from the river

the weaker his position would become and the more exposed his rear and flanks. Accordingly, Pemberton elected to remain on

the defensive, keeping his army as a protective shield between Vicksburg and the Union Army and awaiting an opportunity to

strike a decisive blow—a policy which permitted Grant to march inland unopposed.

With the arrival of Sherman's Corps from Milliken's Bend,

Grant's preparations were complete and, on May 7, the Union Army marched out from Grand Gulf to the northeast. His widely

separated columns moved out on a broad front concealing their objective. Grant's Army alone numbered 35,000 men upon

arrival at Vicksburg, May 18, 1863, but by adding Sherman's command, and the other units arriving almost daily, it increased

and numbered 77,000 strong when Vicksburg capitulated on July 4. To oppose him, Pemberton had available about 50,000

troops, but these were scattered widely to protect important points. On the day of Grant's departure from Grand Gulf, Pemberton's

defensive position was further complicated by orders from President Jefferson Davis that both Vicksburg and Port Hudson must

be held at all cost. The Union Army, however, was already between Vicksburg and Port Hudson and would soon be between Vicksburg

and Jackson. Forced into the already prepared trenches of Vicksburg after the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Big Black

River Bridge, Pemberton's force was reduced to 18,500 effectives.

In comparison with campaigns in the more thickly populated Eastern

Theater, where a more extensive system of roads and railroads was utilized to provide the tremendous quantities of food and

supplies necessary to sustain an army, the campaign of Grant's Western veterans ("reg'lar great big hellsnorters, same breed

as ourselves," said a charitable "Johnny Reb") was a new type of warfare. The Union supply train largely consisted of a curious

collection of stylish carriages, buggies, and lumbering farm wagons stacked high with ammunition boxes and drawn by whatever

mules or horses could be found. (Grant began his Wilderness campaign in Virginia the following year requiring over 56,000

horses and mules for his 5,000 wagons and ambulances, artillery caissons, and cavalry.) Lacking transportation, food supplies

were carried in the soldier's knapsack. Beef, poultry, and pork "requisitioned" from barn and smokehouse enabled the army

which had cut loose from its base to live for 3 weeks on 5 days' rations.

| Vicksburg Battlefield Map |

|

| Map of Battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Strategic Situation of the Civil War in 1862 |

| Battle of Vicksburg Interpretive Marker |

|

| Battle of Vicksburg History Marker |

| Battle of Vicksburg and Union Advance in 1863 |

|

| High Resolution Map of Civil War Western Theater 1863, Battle of Vicksburg, and Union advance |

Grant's

Operations Against Vicksburg, March 29--July 4, 1863: On the banks of this, the greatest river in the world, according

to Confederate Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, the most decisive and far-reaching battle of the war was fought. Here at Vicksburg

over one hundred thousand gallant soldiers and a powerful fleet of gunboats and ironclads in terrible earnestness for forty

days and nights fought to decide whether the new Confederate States should be cut in twain; whether the great river should

flow free to the Gulf, or should have its commerce hindered. The Federal army, commanded by Gen. U.S. Grant, and the Union

navy under Admiral Porter were victorious. The Confederate army was under the command of Gen. John Pemberton and numbered some

thirty thousand men. Although Pemberton's army was captured by Grant, the soldiers were soon paroled and returned to operate in other killing fields of the war. The loss on July 4,

1863, was a staggering blow from which the Confederacy never rallied.

Vicksburg was strategically

vital to the Confederates, because while under their control it blocked Union navigation down the Mississippi. Together

with control of the mouth of the Red River and of Port Hudson to the south, it allowed communication with the states west

of the river, upon which the Confederates depended extensively for horses, cattle and reinforcements. The natural defenses

of the city were ideal, earning it the nickname "The Gibraltar of the Confederacy."

Vicksburg was located on a high bluff overlooking a horseshoe-shaped bend

in the river, De Soto Peninsula, making it almost impossible to approach by ship. North and east of Vicksburg was the

Mississippi Delta (sometimes known as the Yazoo Delta), an area 200 miles north to south and up to 50 miles across, which was

an astonishingly complex network of intersecting waterways some of which were navigable by small steamboats. The regions between

modern rivers and bayous formed closed basins called backswamps, of which were, for all practical purposes, untamed wildernesses,

utterly impassable by a man on horseback or by any form of wheeled vehicle, and very difficult even for a man on foot. About

twelve miles up the Yazoo River were Confederate batteries and entrenchments at Haynes Bluff. The Louisiana land west of Vicksburg

was also difficult, with many streams and poor country roads, widespread winter flooding, and it was on the opposite side

of the river from the fortress.

The city had been under Union naval attack before. Admiral David Farragut

moved up the river after he captured New Orleans and on May 18, 1862, demanded the surrender of Vicksburg. Farragut had insufficient

troops to force the issue, and he moved back to New Orleans. He returned with a flotilla in June 1862, but their attempts

(June 26–28) to bombard the fortress into surrender failed. They shelled Vicksburg throughout July and fought some minor

battles with a few Confederate vessels in the area, but their forces were insufficient to attempt a landing, and they abandoned

attempts to force the surrender of the city. Farragut investigated the possibility of bypassing the fortified cliffs by digging

a canal across the neck of the river's bend, the De Soto Peninsula.

On June 28, Brig. Gen. Thomas Williams, attached to Farragut's command,

began digging work on the canal by employing local laborers and some soldiers. Many of the men fell victim to tropical diseases

and heat exhaustion, and the work was abandoned by July 24. Williams was killed two weeks later in the Battle of Baton Rouge.

In the fall of 1862, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck was promoted from command

of the Western Theater to general-in-chief of all Union armies. On November 23, he stated to Grant his preference for

a major move down the Mississippi to Vicksburg. In Halleck's style, he left considerable initiative to design a campaign,

an opportunity that Grant seized. Halleck had received criticism for not moving promptly overland from Memphis, Tennessee,

to seize Vicksburg during the summer when he was in command on the scene. He believed that the Navy could capture the fortress

on its own, not knowing that the naval force was insufficiently manned with ground troops to finish the feat. What might have

achieved success in the summer of 1862 was no longer possible by November because the Confederates had amply reinforced the

garrison by that time.

Grant's army marched south down the Mississippi Central Railroad, making

a forward base at Holly Springs. He planned a two-pronged assault in the direction of Vicksburg. His principal subordinate,

Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, was to advance down the river with four divisions (about 32,000 men) and Grant would continue

with the remaining forces (about 40,000) down the railroad line to Oxford, where he would wait for developments, hoping to

lure the Confederate army out of the city to attack him in the vicinity of Grenada, Mississippi. On the Confederate side,

forces in Mississippi were under the command of Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, an officer from Pennsylvania who chose to fight

for the South. Pemberton had approximately 12,000 men in Vicksburg and Jackson, Mississippi, and Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn had

approximately 24,000 at Grenada.

| Battle of Vicksburg Map |

|

| Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg, which spanned 97-days, included the 47-day Siege of Vicksburg |

| Battle of Vicksburg Cannons |

|

| Federal Battery Sherman during Siege of Vicksburg. June 1863 |

| Battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi |

|

| South Fort was on the Confederate right flank below Vicksburg |

(Left) South Fort, overlooking the Mississippi, was located south and

on the flank of the Confederate defenses below Vicksburg. Interior of South Fort, showing the heavy type of Columbiads

and mortars which made up the battery here. The Columbiads, which were being retired by the Union army, were older smoothbore

guns that were found in greater quantity in the Confederate arsenal, and the mortars could lob a 200-pound shell

at a high trajectory making the interior of forts vulnerable. To protect themselves from the mortars, both sides would construct

bombproofs as a defense. As with any weapon of war, both distance and shielding between the soldier and threat is the

objective in the defense. (Right) Battery Sherman, on the Jackson Road,

before Vicksburg. The heavy guns of this Union siege battery were borrowed from the Federal gunboats and used against the

Confederate siege defenses. Settling down to a siege did not mean idleness for Grant’s army. Fortifications had to be

opposed to the formidable one of the Confederates and a constant bombardment kept up to silence their guns, one by one. It

was to be a drawn-out duel in which Pemberton, hoping for the long-delayed relief from Johnston, held out bravely against

starvation and even mutiny. For twelve miles the Federal lines stretched around Vicksburg, investing it to the river bank,

north and south. More than eighty-nine battery positions were constructed by the Federals. Battery Sherman was exceptionally

well built—not merely revetted with rails or cotton-bales and floored with rough timber, as lack of proper material

often made necessary. Gradually the lines were drawn closer and closer as the Federals moved up their guns to silence the

works that they had failed to take in May. At the time of the surrender Grant had more than 220 guns in position, mostly of

heavy caliber. By the 1st of July besieged and besiegers faced each other at a distance of half-pistol shot. Starving and

ravaged by disease, the Confederates had repelled repeated attacks which depleted their forces, while Grant, reinforced to

three times their number, was showered with supplies and ammunition that he might bring about the long-delayed victory which

the North had been eagerly awaiting since Chancellorsville.

Meanwhile, political forces were at work. President Abraham Lincoln had

long recognized the importance of Vicksburg; he wrote "Vicksburg is the key. The war can never be brought to a close until

the key is in our pocket." Lincoln also envisioned a two-pronged offensive, but one up and down the river. Maj. Gen. John

A. McClernand, a War Democrat politician, had convinced Lincoln that he could lead an army down the river and take Vicksburg.

Lincoln approved his proposal and wanted Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks to advance up river from New Orleans at the same time.

While McClernand began organizing regiments, sending them to Memphis, back

in Washington, D.C., Halleck was nervous about McClernand and gave Grant control of all troops in his own department. McClernand's

troops were split into two corps, one under McClernand, the other under Sherman. McClernand complained but to no avail. Grant

appropriated his troops, one of several maneuvers in a private dispute within the Union Army between Grant and McClernand

that would continue throughout the campaign.

For the Union, the spring of 1863 signaled the beginning of the final and

successful phase of the Vicksburg Campaign as Gen. Grant initiated the march of his Army of the Tennessee down the west side

of the Mississippi River, from Milliken's Bend to Hard Times, Louisiana. Leaving their encampments on March 29, 1863, Federal

soldiers took up the line of march and slogged southward over muddy terrain, building bridges and corduroy roads as they went.

Grant's column pushed first to New Carthage, then to Hard Times, where the infantrymen rendezvoused with the Union navy.

On April 16, while Grant's army marched south through Louisiana, part of the Union fleet,

commanded by Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, prepared to run by the Vicksburg batteries. At 9:15 p.m., lines were cast off

and the vessels moved away from their anchorage above the city with engines muffled and all lights extinguished to conceal

their movement.

As the boats rounded De Soto Point, they were spotted by Confederate

lookouts who spread the alarm. Bales of cotton soaked in turpentine and barrels of tar lining the shore, were set on fire

by the Southerners to illuminate the river. Although each vessel was hit repeatedly, Porter's fleet successfully fought its

way past the Confederate batteries losing only one transport, and headed downriver to the rendezvous with Grant on the Louisiana

shore south of Vicksburg.

It was Grant's intention to force a crossing of the river at Grand Gulf,

and move on "Fortress Vicksburg" from the south. For five hours on April 29, the Union fleet bombarded the Grand Gulf defenses

in an attempt to silence the Confederate guns and prepare the way for a landing. The fleet, however, sustained heavy damage

and failed to achieve its objective. Admiral Porter declared, "Grand Gulf is the strongest place on the Mississippi." Not

wishing to have his transports loaded with troops attempt a landing in the face of enemy fire, Grant disembarked his command

and continued the march south along the levee.

After crossing the Mississippi River south of Vicksburg at Bruinsburg and

driving northeast, Grant won battles at Port Gibson and Raymond and captured Jackson, the Mississippi state capital on May

14, 1863, forcing Pemberton to withdraw westward. Attempts to stop the Union advance at Champion Hill and Big Black River

Bridge were unsuccessful. Pemberton knew that the corps under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman was preparing to flank him from

the north; he had no choice but to withdraw or be outflanked. Pemberton burned the bridges over the Big Black River and took

everything edible in his path, both animal and plant, as he retreated to the well-fortified, prepared defenses in the city

of Vicksburg.

| Battle of Vicksburg |

|

| Civil War Battle of Vicksburg Map |

| Hand Grenades at the Battle of Vicksburg |

|

| Hand Grenades during the Siege of Vicksburg |

| Siege of Vicksburg and Third Louisiana Redan |

|

| Hand-to-hand fighting at Vicksburg Crater |

| Third Louisiana Redan Mine |

|

| Vicksburg Crater and the Third Louisiana Redan History |

(About) June 25--26, 1863. Explosion of the mine under the Third Louisiana Redan would create a crater

measuring 12 feet deep and 40 feet wide. On June 25, 1863, as the entire Union line opened fire to prevent shifting of reinforcements, a

charge of 2,200 pounds of powder would be exploded beneath the Third Louisiana Redan, creating a large crater into which elements

of the 23rd Indiana and 45th Illinois raced from the approach trench. Anticipating this result, however, Confederate Gen.

Forney had prepared a second line of works in the rear of the fort where survivors of the blast and supporting regiments met

the Union attack to drive it back. More than 30 hours of hand-to-hand fighting would ensue before the Federals,

without gaining an advantage, withdrew on June 26. Because the siege of Vicksburg would continue

beyond the June 25 explosion, Union engineers would construct additional mines, but with no relief in sight or sound,

Gen. John C. Pemberton would commit to surrender, and Gen. Ulysses S. Grant would dine in Vicksburg on July 4, as he

had promised.

| Vicksburg Civil War History |

|

| U.S. Flag raised over Vicksburg Courthouse |

Undaunted by his failure at Grand Gulf, Grant moved farther south in search

of a more favorable crossing point. Looking now to cross his army at Rodney, Grant was informed that there was a good road

ascending the bluffs east of Bruinsburg. Seizing the opportunity, the Union commander transported his army across the mighty

river and onto Mississippi soil at Bruinsburg on April 30—May 1, 1863. In the early morning hours of April 30, infantrymen

of the 24th and 46th Indiana Regiments stepped ashore on Mississippi soil at Bruinsburg. The invasion had begun.

The landing was made unopposed and, as the men came ashore, a band aboard

the U.S.S. Benton struck up "The Red, White, and Blue." The Hoosiers were quickly followed by the remainder of the XIII Union

Army Corps and portions of the XVII Corps — 17,000 men. This landing was the largest amphibious operation in American

military history until the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II. Elements of the Union army pushed inland and took

possession of the bluffs, thereby securing the landing area. By late afternoon of April 30, 17,000 soldiers were ashore and

the march inland began. Moving away from the landing area at Bruinsburg, the Federal soldiers rested and ate their crackers

in the shade of the trees on Windsor Plantation. Late that afternoon the decision was made to push on that night by a forced

march in hopes of surprising the Confederates and preventing them from destroying the bridges over Bayou Pierre. The Union

columns resumed the advance at 5:30 p.m., but instead of taking the Bruinsburg Road — the most direct road from the

landing area to Port Gibson — Grant's columns swung onto the Rodney Road, passing Bethel Church and marching through

the night.

On April 30, 1863, the Confederate brigades of brigadiers Martin Green and

Edward Tracy marched south along the Bruinsburg Road to contest the Union invasion of Mississippi. The next day, May 1, the

brigades of Brig. Gen. William Baldwin and Col. Francis Cockrell hastened out the Bruinsburg road to reinforce the Confederate

troops then heavily engaged with Grant's forces. Late in the afternoon of May 1, Baldwin's men would retire from the field

along the road into Port Gibson followed by the victorious Union soldiers.

Confederate troops were deployed to block both the Rodney and Bruinsburg

Roads west of Port Gibson. At the point of deployment, an interval of 2,000 yards separated the roads. The brigades of Tracy,

on the right, and Green, on the left, who was strengthened by four guns of the Pettus Flying Artillery, were separated by

a deep cane-choked ravine which prevented one flank from reinforcing the other flank. To do so, the Confederates had to march

back to the road junction. The "Y" intersection of the roads was thus the lateral avenue of movement for the Confederates.

Shortly after midnight the crash of musketry shattered the stillness as

the Federals stumbled upon Confederate outposts near the A. K. Shaifer house. The Battle of Port Gibson had begun. Union troops

immediately deployed for battle, and their artillery, which soon arrived, roared into action. A spirited skirmish ensued which

lasted until 3 a.m, May 1, with the Confederates holding their ground. For the next several hours an uneasy calm settled over

the woods and scattered fields as soldiers of both armies rested on their arms. Throughout the night the Federals gathered

their forces in hand and both sides prepared for the battle which they knew would come with the rising sun.

At dawn, Union troops began to move in force along the Rodney Road

toward Magnolia Church. One division was sent along a connecting plantation road toward the Bruinsburg Road and the Confederate

right flank. With skirmishers well ahead, the Federals began a slow and deliberate advance around 5:30 a.m. The Confederates

contested the thrust and the battle began in earnest.

Most of the Union forces moved along the Rodney Road toward

Magnolia Church and the Confederate line held by Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green's Brigade. Heavily outnumbered and hard-pressed,

the Confederates gave way shortly after 10:00 a.m. The men in butternut and gray fell back a mile and a half. Here the soldiers

of Brig. Gen. William E. Baldwin's and Col. Francis M. Cockrell's brigades, recent arrivals on the field, established a new

line between White and Irwin branches of Willow Creek. Full of fight, these men re-established the Confederate left flank.

The morning hours witnessed Green's Brigade driven from its position by

the principle Federal attack. Brig. Gen. Edward D. Tracy's Alabama Brigade, astride the Bruinsburg Road, also experienced

hard fighting. Although Tracy was killed early in the action, his brigade managed to hold its tenuous line.

It was

clear, however, that unless the Confederates received heavy reinforcements, they would lose the day. Brig. Gen. John S. Bowen,

Confederate commander on the field, wired his superiors: "We have been engaged in a furious battle ever since daylight;

losses very heavy. The men act nobly, but the odds are overpowering." Early afternoon found the Alabamans slowly giving

ground. Green's weary soldiers, having been regrouped, arrived to bolster the line on the Bruinsburg Road.

Even so,

by late in the afternoon on May 1, the Federals had advanced all along the line in superior numbers. As Union pressure built,

Cockrell's Missourians unleashed a vicious counterattack near the Rodney Road, and began to roll up the blue line. The 6th

Missouri also counterattacked, hitting the Federals near the Bruinsburg Road. All this was to no avail, for the odds against

them were too great. The Confederates were checked and driven back, the day lost. At 5:30 p.m., battle-weary Confederates

began to retire from the hard-fought field, and thus the engagement at Port Gibson had

ended.

| Battle of Vicksburg History |

|

| Siege of Vicksburg |

| Map showing Vicksburg Campaign battles |

|

| Vicksburg Campaign battles, Union and Confederate troop movements, and investment of Vicksburg |

| Battle of Vicksburg |

|

| Stockade Redan, Vicksburg, present-day |

(Right) Looking down Graveyard

Road toward Stockade Redan, this is the same vantage point held by the Union soldiers as they moved along

the road and assaulted the redan during May 1863, and it was here that Union troops would advance and force

Grant's investment on target Johnny Reb at Stockade Redan directly to their front. The redan was an inexpensive,

elementary earthwork that must be taken, according to Grant, so Billy Yank's artillery, which was in plain sight of the redan,

had trained its guns and leveled much tonnage into the nearly 20-foot thick salient since the Federal's arrival.

The Union army would assault Stockade Redan twice, initially on May 19 and lastly on May 22, but as the redan demonstrated

that neither iron nor steel could subdue the earthwork, and with Federal casualties now over 4,000, the frustrated

Grant would reluctantly resort to siege activities.

Union losses at the Battle of Port Gibson were 131 killed, 719 wounded,

and 25 missing out of 23,000 men engaged. This victory not only secured his position on Mississippi soil, but enabled him

to launch his campaign deeper into the interior of the state. Union victory at Port Gibson forced the Confederate evacuation

of Grand Gulf and would ultimately result in the fall of Vicksburg.

The Confederates suffered 56 killed, 328

wounded, and 341 missing out of 8,000 men engaged. In addition, 4 guns of the Botetourt (Virginia) Artillery were lost. The

action at Port Gibson underscored Confederate inability to defend the line of the Mississippi River and to respond to amphibious

operations. The Rebel soldiers from these operations were buried at Wintergreen Cemetery in Port Gibson.

To support the army's push inland, Grant established a base on the Mississippi

River at Grand Gulf. Contrary to assertions by modern-day historians, the Union army relied heavily on the Grand Gulf supply

base to sustain its movements in Mississippi. Only after reaching Vicksburg and reestablishing contact with the fleet on the

Yazoo River, did Grant abandon this vital supply line.

On May 2, instead of marching directly on Vicksburg from the

south, Grant marched his army in a northeasterly direction, his left flank protected by the Big Black River. It was his intention

to strike the Southern Railroad of Mississippi somewhere between Vicksburg and Jackson. Destruction of the railroad would

cut Pemberton's supply and communications lines, and isolate Vicksburg. As the Federal force moved inland, McClernand's Corps

was positioned on the left, Sherman's in the center, and McPherson's on the right.

On the morning of May 12, 1863, Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson's XVII

Corps marched along the road from Utica toward Raymond. Shortly before 10:00 a.m., the Union skirmish line crested a ridge,

and moved cautiously through open fields into the valley of Fourteen Mile Creek, southwest of Raymond. Suddenly a deadly volley

ripped into their ranks from the woods lining the nearly dry stream.

As the battle progressed, McPherson massed 22 guns astride the road to support

his infantry, while Confederate artillery also roared into action, announcing the presence of Brig. Gen. John Gregg's battle-hardened

brigade. The ever-combative Gregg decided to strike with his 3,000-man brigade, turn the Federal right flank, and capture

the entire force. Faulty intelligence led Gregg to believe that he faced only a small Union force, when in reality McPherson's

10,000-man corps was on the road before him.

Thick clouds of smoke and dust obscured the field and neither commander

accurately assessed the size of the force in his front. Gregg enjoyed initial success, but as successive Confederate regiments

attacked across the creek to the left, resistance stiffened and it became clear that a much larger Federal force was on the

field. By early afternoon, the Confederate assault was checked and Union forces counterattacked.

Union brigades continued to arrive on the field and deploy in line of battle

on either side of the Utica road. In piecemeal fashion, McPherson's men pushed forward at 1:30 p.m., driving the Confederates

back across Fourteen Mile Creek. The ensuing fight was of the most confused nature, for neither commander knew where their

units were or what they were doing.

However, Union strength of numbers prevailed. The Confederate right flank along

the Utica road broke under renewed pressure, and Gregg had no alternative but to retire from the field. His regiments retreated

through Raymond along the Jackson Road, bivouacking for the night near Snake Creek. There was no Federal pursuit as McPherson's

troops bedded down for the night in and around the town.

The fight at Raymond cost Gregg 73 killed, 251 wounded, and

190 missing, most of whom were from the 3rd Tennessee and the 7th Texas. McPherson's losses totaled 442 of whom 66 were killed,

339 wounded, and 37 missing.

The Battle of Raymond led Grant to change the direction of his army's

march and move on Jackson, the state capital. It was the Union general's intention to destroy the important rail and communications

center in the city, and scatter any Confederate reinforcements which might be moving toward Vicksburg. McPherson's Corps moved

north through Raymond to Clinton on May 13, while Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman pushed northeast through Raymond to Mississippi

Springs. To cover the march on Jackson, Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand's Corps was placed in a defensive position on a line

from Raymond to Clinton.

| Battle and Siege of Vicksburg Map |

|

| The Battle of Vicksburg demonstrated Union determination against Confederate mettle. |

| Battle of Vicksburg and the Civil War |

|

| Battle of Big Black River Bridge resulted in the Confederate move into the trenches of Vicksburg |

Late on the afternoon of May 13, as the Federals were poised to strike at

Jackson, a train arrived in the capital city carrying Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, ordered to the city by President

Jefferson Davis to salvage the rapidly deteriorating situation in Mississippi. Establishing his headquarters at the Bowman

House, Gen. Johnston was apprised of troop strength and the condition of the fortifications around Jackson. He immediately

wired authorities in Richmond, "I am too late," and instead of fighting for Jackson, ordered the city evacuated.

John Gregg was ordered to fight a delaying action to cover the evacuation.

A heavy rain fell during the night, turning the roads into mud. Advancing

slowly through the torrential downpour, the corps of Sherman and McPherson converged on Jackson by mid-morning of May 14.

Around 9 a.m., the lead elements of McPherson's corps were fired upon by Confederate artillery posted on the O. P. Wright

farm. Quickly deploying his men into line of battle, the Union corps commander prepared to attack. Suddenly, the rain fell

in sheets and threatened to ruin the ammunition of his men by soaking the powder in their cartridge-boxes. The attack was

postponed until the rain stopped around 11:00 a.m. The Federals then advanced with bayonets fixed and banners unfurled. Clashing

with the Confederates in a bitter hand-to-hand struggle, McPherson's men forced the Southerners back into the fortifications

of Jackson.

Meanwhile, Sherman's corps reached Lynch Creek southwest of Jackson at 11 a.m. and was immediately fired

upon by Confederate artillery posted in the open fields north of the stream. Union cannon were hurried into position, and

in short order drove the Confederates back into the city's defenses. The stream was unfordable, forcing Sherman's men to cross

on a narrow wooden bridge. Reforming their lines, the Federals advanced at 2:00 p.m. until they were stopped by canister fire.

Not wishing to expose his men to the deadly fire, Sherman sent one regiment to the right (east) in search of a weak spot in

the defense line. These men reached the works and found them mainly deserted, with only a handful of state troops and civilian

volunteers left to man the guns in Sherman's front.

At 2:00 p.m., Gregg was notified that the army's supply train had left Jackson

and decided to withdraw his command. The Confederates moved quickly to evacuate the city and were well out the Canton Road

to the north when Union troops entered Jackson around 3 p.m., May 14. The "Stars and Stripes" were unfurled atop

the capital by McPherson's men, symbolic of Union victory.

Confederate casualties for the Battle of Jackson were incomplete, but an

initial report indicated 17 killed, 64 wounded, and 118 missing, for a preliminary tally of 199. In

addition, 17 artillery pieces were taken by the Federals. Union casualties totaled 300 men, of whom 42 were killed, 251 wounded,

and 7 missing.

Not wishing to waste foot soldiers on occupation, Grant ordered Jackson neutralized militarily. The

torch was applied to machine shops and factories, telegraph lines were cut, and railroad tracks destroyed. With Jackson's

resources rendered ineffective, and Johnston's force scattered to the winds, Grant turned with confidence toward his objective

to the west — Vicksburg.

Following the Union occupation of Jackson, Mississippi, both Confederate

and Federal forces made plans for future operations. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston retreated, with most of his army, up the Canton

Road, but he ordered Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, commanding about 23,000 men, to leave Edwards Station and attack the Federals

at Clinton. Pemberton and his generals felt that Johnston’s plan was dangerous and decided instead to attack the Union

supply trains moving from Grand Gulf to Raymond.

On May 16, though, Pemberton received another order from Johnston reiterating

his former directions. Pemberton had already moved after the supply trains and was on the Raymond-Edwards Road with his rear

at the crossroads one-third mile south of the crest of Champion Hill. Thus, when he ordered a countermarch, his rear, including

his many supply wagons, became the advance of his force. On May 16, at approximately 7:00 am, the Union forces engaged the

Confederates and the Battle of Champion Hill began.

Pemberton’s force drew up into a defensive line along a crest of a

ridge overlooking Jackson Creek. Pemberton was unaware that one Union column was moving along the Jackson Road against his

unprotected left flank. For protection, Pemberton posted Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Lee's men atop Champion Hill where they could

watch for the reported Union column moving to the crossroads. Lee spotted the Union troops and they soon saw him. If this

force was not stopped, it would cut the Rebels off from their Vicksburg base. Pemberton received warning of the Union movement

and sent troops to his left flank.

Union forces at the Champion House moved into action and emplaced artillery

to begin firing. When Grant arrived at Champion Hill, around 10:00 am, he ordered the attack to begin. By 11:30 am, Union

forces had reached the Confederate main line and about 1:00 pm, they took the crest while the Rebels retired in disorder.

The Federals swept forward, capturing the crossroads and closing the Jackson Road escape route. One of Pemberton's divisions

(Bowen’s) then counterattacked, pushing the Federals back beyond the Champion Hill crest before their surge came to

a halt. Grant then counterattacked, committing forces that had just arrived from Clinton by way of Bolton. Pemberton’s

men could check this assault, so he ordered his men from the field to the one escape route still open: the Raymond Road crossing

of Bakers Creek. Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman’s brigade formed the rearguard, and they held at all costs, including the

loss of Tilghman. In the late afternoon, Union troops seized the Bakers Creek Bridge, and by midnight, they occupied Edwards.

The Confederates, now routed, were in full retreat towards Vicksburg. If the Union forces caught these Rebels, they would

destroy them.

Tilghman's Brigade had pulled back from the Coker House to the ridge, known

as Cotton Hill. Company G, 1st Mississippi Light Artillery (Cowan's Battery), straddled the road with two guns to the north

and four guns to the south. Gen. Tilghman, having dismounted, was personally giving directions regarding the sighting

of one of the guns north of the road, when he was struck by a shell fragment and instantly killed. Immediately

following the withdrawal of Confederate forces, Union troops took possession of the ridge. Six guns of the Chicago Mercantile

Battery were positioned between the Raymond Road and the Coker House, which was eventually utilized as a field hospital for

soldiers of both North and South.

The Battle of Champion Hill was costly for both armies. Union casualties

totaled 2,441, with 410 killed, 1,844 wounded, and 187 missing, and Confederate losses were 380 killed, 1,018 wounded,

and 2,453 missing and captured, for a total of 3,851.

| Battle of Vicksburg |

|

| Abraham Lincoln |

| Battle of Vicksburg Map |

|

| Map of Siege of Vicksburg, and Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg |

| Siege and Battle of Vicksburg Map |

|

| Stockade Redan was the earthwork where most Union casualties occurred at Vicksburg |

| Vicksburg Civil War Battlefield |

|

| Stockade Redan Characteristics |

(About) Stockade Redan on May 19 and 22, 1863. Stockade

Redan was the location of the two deadliest days of the 47-day Siege of Vicksburg. The fort, located on Graveyard

Road, was a very thick, strong earthwork that acted as the gatekeeper and defender of Vicksburg, and, knowing that it was

the most likely target of any Union attack on the city, the Confederates had constructed it well. On both flanks were innumerable

natural and manmade obstructions that would force the Union army to attack from Graveyard Road. Nearby Confederate works would

also place any Union assault in a fierce crossfire that resembled Shiloh's "hornets nest." While only few

Confederate reinforcements could be expected, the small, 300-man garrison at Stockade Redan was to the Rebels at

Vicksburg what the Hot Gates was to Leonidas and his 300 against the Persians at the Battle of Thermopylae. The two failed

frontal assaults on the earthen redan (May 19 and 22) produced more than 4,100 Union men in killed, wounded, and

missing, and Grant, with his army now hemorrhaging, reluctantly, but wisely, resigned his army to a siege while

deadlocked before the gates of Vicksburg. Whereas the Siege of Vicksburg lasted from May 18 to July 4, 1863, the siege

operations actually didn't begin until May 23, the day after Grant's second failed assault on the redan. Grant,

who commanded an army of some 35,000 strong, arrived on the outskirts of Vicksburg on May 18, and on the following day he pressed and assaulted the Confederate works with the

objective of sweeping the Rebels from the field and capturing Vicksburg immediately-- but it didn't materialize.

On May 22, Grant, now agitated and more determined to break that redan, massed an even greater number of men for the imminent

advance on the works. Preceding the attack, during the night of the 21st, many of the 220 Union artillery pieces had

been adjusted to fire for effect on Stockade Redan. The cannonading would continue through the night followed by a short respite

before being resumed on the following day. But similar to

his initial, ill-fated attack on the 19th, Grant's units became entangled and delayed by the many obstructions

and mines while en route to the 20-foot high earthwork. Union units were being badly beaten and pushed back. Reform

your men, were the orders to the regimental commanders, and then press and take that redan. The fighting was furious and

with some Federals arriving with scaling ladders now in the ditch below the redan, some progress was observed.

A few ladders and planks were seen rising on the salient-- but they were too short to be of use. Only a few feet separated

the enemies, but now, with the number of blue uniforms increasing in the ditch

below, the gray-clad men began tossing grenades while rolling charges down the embankment and onto the Federals.

The 8-foot wide ditch, which had served its purpose well, was now a welcoming grave to the once persistent Union men

who had fought so bravely to reach it. Stockade Redan remained intact, and it would not be assaulted for the duration

of the siege. Grant, who would later become the 18th U.S. President, received his after battle reports showing 502 killed, 2,550 wounded, and 147 missing,

for a grand total of 3,199 Union casualties. Coupled with the nearly 1,000 casualties that the Union army had sustained on

May 19, Grant made the obvious decision to besiege the city. Grant was a fighter, but in spite of the fact that he knew

that he had been beaten badly at the redan, his only regret was that did not succeed. Although Grant was receiving reinforcements

from Maj. Gen. Halleck almost daily, he knew very well that a Confederate force was gathering nearby in hopes of breaking

the siege and relieving Pemberton's beleaguered Confederates. A Northern army deep in Dixie couldn't remain static, and

Grant understood that. With the sunset on May 22, the

Federals, having licked their wounds, waited for additional orders. The Rebels, however, held the advantage

as long as Grant forwarded his army in piecemeal fashion down the long narrow Graveyard Road, which was lined with many

obstructions on both sides, and headlong into the clutch of well-defended Confederates in and near the redan. As the

redan was attacked several times on those two days of May, the course of the Rebs was merely to aim and then pull

the trigger of their muskets, and then observe the heavily concentrated ranks of Union soldiers collapse and

bottle up the approach. While the Siege of Vicksburg was a proving ground for Grant,

unbeknownst to the general, he would also be engaged in the longest siege of the war during the following summer, against

General Robert E. Lee before Richmond.

| Campaign of Vicksburg Map |

|

| Battle and Siege of Vicksburg Map |

Following the Battle of Champion Hill, the Confederates retreated to Big

Black River Bridge, where Pemberton ordered Bowen's division, and a fresh brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. John Vaughn, to

hold the bridges across Big Black River long enough for Gen. Loring to cross. Unbeknownst to Pemberton, however, Loring was

not marching toward the river, but instead northeast, to join with the forces of Gen. Johnston. Federal troops appeared early

in the morning of May 17, and prepared to storm the defenses, with McClernand's XIII Corps quickly deploying along the

road and Union artillery opening on the Confederate fortifications with solid shot and shell.

The Confederate line was naturally strong, and formed an arc with its left

flank resting on Big Black River and the right flank on Gin Lake. A bayou of waist-deep water fronted a portion of the line,

and 18 cannon were placed to sweep the flat open ground to the east. As both sides prepared for battle, Union troops took

advantage of terrain features and Brig. Gen. Mike Lawler, on the Federal right, deployed his men in a meander scar not far

from the Southern line of defense.

Believing that his men could cover the intervening ground quickly, and with little

loss, Lawler boldly ordered his troops to fix bayonets and charge. With a mighty cheer the Union troops swept across the open

ground, through the bayou, and over the parapets. From beginning to end, the charge lasted three minutes.

Overwhelmed by the charge, Confederate soldiers threw down their rifle-muskets

and began to withdraw across the Big Black on two bridges: the railroad bridge and the steamboat dock moored athwart

the river. As soon as they had crossed, the Confederates set fire to the bridges, preventing close Union pursuit. In the panic

and confusion of defeat, many Confederate soldiers attempted to swim across the river and drowned. Luckily, Pemberton's chief engineer, Major Samuel Lockett, set the bridges on fire, effectively

cutting off pursuit by the victorious Union army. Badly shaken, the Confederates staggered back into the Vicksburg defenses

and prepared to resist the Union onslaught.

Confederate losses at the Battle of Big Black River Bridge, though not

accurately reported, were initially stated as 3 killed, 9 wounded, and 539 missing, making a total of 553 casualties.

A Union after battle report, also incomplete, showed 1,751 total Confederate casualties, with 18 cannon and

5 battle flags captured by the Federals. Union casualties totaled 279 men, of whom 39 were killed, 237 wounded,

and 3 missing. Grant's forces bridged the river at three locations and, flushed with victory, pushed hard toward Vicksburg

on May 18.

The Confederates evacuated Hayne's Bluff, which was occupied by Sherman's

cavalry on May 19, and Union steamboats no longer had to run the guns of Vicksburg, now being able to dock by the dozens up

the Yazoo River. Grant could now receive supplies more directly than by the previous route, which ran through Louisiana, over

the river crossing at Grand Gulf and Bruinsburg, then back up north.

Over three quarters of Pemberton's army had been lost in the two preceding

battles and many in Vicksburg expected Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, in command of the Confederate Department of the West, to relieve

the city—which he never did. Large masses of Union troops were on the march to invest the city, repairing the burned

bridges over the Big Black River; which Grant's forces crossed on May 18. Johnston sent a note to his general, Pemberton,

asking him to sacrifice the city and save his troops, a request that Pemberton would not follow.

Forced Back to Vicksburg: After the Confederate

rout at Big Black River, the Rebels, which had been scattered, regrouped as they fell back to their rally point, Vicksburg, a

natural bulwark with well-prepared defenses making it a fortress on the bluffs. Vicksburg

was some 200-feet above the Mississippi River and its terrain was canvassed was knolls and rolling hills as it stretched inland and into the Mississippi Delta.

It was ideal for defense, and having already proved itself, Vicksburg was the last Southern bastion and holdout

along the Mississippi. The position placed the river to the Confederate rear, the swamp to the north, and the Federals

checked all other directions, including a riverine flotilla which would shell the Rebels daily.

The Confederates who

would now have the gunboats to their back and the large Union army to the front, only had one option, to fight, and that

was exactly why the scattered units had fallen back to the locale. This was it, this was the last stand, and in

Alamo fashion, the Confederates would unleash from their defensive works, one of the most stubborn fights of the entire

war. Ranking as the battle that sustained the tenth highest casualties of the Civil War bears witness to the contest that

would soon ensue.

If Vicksburg was truly the Rebel Alamo, then Stockade Redan served

as its inner room, the quarters that housed the ill-stricken Bowie, but to access it meant that the walls had to first

be breached. The Confederates had been thrashed and routed from

Port Gibson, Raymond, Champion Hill, Big Black River Bridge, and Jackson, the capital, to name just some of the more

recent battles in Mississippi, and having been pushed from field to field, they now rallied at Vicksburg and, although

battered and bloodied, the soldiers were determined that this was the place that they were going to make the Yankees pay.

| Vicksburg Battlefield Map |

|

| Vicksburg Battlefield Map. NPS |

| Siege of Vicksburg |

|

| Battle of Vicksburg and Union Assault on Stockade Redan |

Siege of Vicksburg,

May 18--July 4, 1863: As the Union forces approached Vicksburg, Pemberton could field only 18,500 of his more

than 33,000 troops. Grant had over 35,000 effectives when he arrived at Vicksburg, and shortly after the siege began,

Union forces swelled to more than 50,000, and additional soldiers were arriving almost daily from Memphis. Maj. Gen.

Henry W. Halleck, the Union general-in-chief, began shifting Union troops in the West to assist Grant in the siege. The

first of these reinforcements to arrive along the siege lines was a 5,000 man division from the Department of the Missouri

under Maj. Gen. Francis J. Herron on June 11. Herron's troops, remnants of the Army of the Frontier, were attached to McPherson's

corps and took up position on the far south. Next came a three division detachment from the XVI Corps led by Brig. Gen. Cadwallader

C. Washburn on June 12, assembled from troops at nearby posts of Corinth, Memphis, and LaGrange. The final significant group

of reinforcements to join was the 8,000 man strong IX Corps (two divisions) from the Department of the Ohio, led by Maj.

Gen. John G. Parke, arriving on June 14. With the arrival of Parke, Grant had 77,000

men around Vicksburg.

Confederate Gen. Johnston, meanwhile, would

mass an army of more than 31,000 strong, but his constant delays and inaction had allowed Grant plenty of time to

assemble a rear guard of 36,000 men under the command of Gen. Sherman, thus checking any possible threat to the siege. There

would be no relief for Pemberton's men-- just a grueling and horrid siege followed by surrender.

| Battle of Vicksburg History |

|

| Siege of Vicksburg |

(Right) While many historians group the actions at Vicksburg into

a single campaign lasting from March 29 to July 4, 1863, the dates that the siege portion began and ended vary. Upon his immediate

arrival at Vicksburg, Grant ordered two bloody, ill-fated assaults on May 19 and 22, but, having been

repulsed, the Union general would begin the Siege of Vicksburg on May 23.

President

Abraham Lincoln told his political and military leaders, "See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which

Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.... We can take all the northern

ports of the Confederacy, and they can defy us from Vicksburg." Lincoln assured his listeners that "I am acquainted

with that region and know what I am talking about, and as valuable as New Orleans will be to us, Vicksburg will be more so."

It was imperative for the administration

in Washington to regain control of the lower Mississippi River, thereby opening that important avenue of commerce enabling

the rich agricultural produce of the Northwest to reach world markets. It would also split the South in two, sever

a vital Confederate supply line, achieve a major objective of the Anaconda Plan, and effectively seal the doom of Richmond.

In the spring of 1863, Major General Ulysses S. Grant moved his massive Army of the Tennessee on a campaign to pocket Vicksburg

and provide Mr. Lincoln with the key to victory.

At the time of the Civil War, the Mississippi River was the single

most important economic feature of the continent-- the very lifeblood of America. Upon the secession of the Southern states,

Confederate forces closed the river to navigation, which threatened to strangle Northern commercial interests.

The prize of Mississippi was thought to be impregnable by most strategists

of the war. By 1863, Vicksburg was the last major Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River, controlling the transport

of troops, supplies and arms along a significant stretch of the river. The city was well defended on three sides by topography

— 200-foot bluffs mounted with guns overlooking the river to the west, impassable swamps and bayous to the north and

south — and on the east by a fortification-lined ridge. The Vicksburg

Campaign consisted of many important naval operations, troop maneuvers, failed initiatives, and eleven distinct battles from

December 26, 1862, to July 4, 1863. Military historians divide the campaign into two formal phases: Operations Against Vicksburg

(December 1862—January 1863) and Grant's Operations Against Vicksburg (March-–July 1863).

The Siege of Vicksburg (May 18–-July 4, 1863) was the final major

military action in the Vicksburg Campaign of the Civil War. In a series of maneuvers, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

and his Army of the Tennessee crossed the Mississippi River and drove the Confederate Army of Vicksburg, led by Lt. Gen. John

C. Pemberton, into the defensive lines surrounding the fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. When

two major assaults (May 19 and 22, 1863) against the Confederate fortifications were repulsed with heavy casualties, Grant

decided to besiege the city beginning on May 25. Without reinforcements, supplies nearly gone, and after holding out for more

than forty days, the garrison finally surrendered on July 4. This action, combined with the surrender of Port Hudson to Maj.

Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks on July 9, yielded command of the Mississippi River to the Union forces, who would hold it for the

rest of the conflict.

Grant had absolutely no desire of relaxing in trenches and bombproofs during a siege, for his campaign was

based on speed—speed, and light rations foraged off the country, and no baggage, nothing at the front but men and guns

and ammunition, and no rear; no slackening of effort, no respite for the enemy until Vicksburg itself was invested and

fell. To remain idle invites complacency. To stay in one place very deep in the South brings the opportunity of reinforcements

for the Rebels, so Grant, being a fighter, was going to press the fight, even if the Confederates stayed in their holes.

Grant’s offensive in the siege of Vicksburg,

Mississippi, began in late 1862 with setbacks. Confederate cavalry captured Grant's

supply base at Holly Springs, and William

T. Sherman's premature assault on Vicksburg failed. After

a winter of frustration, Grant's supporting fleet ran past the batteries and landed troops south of Vicksburg. Grant then unexpectedly struck the capital at Jackson,

Mississippi, before turning toward Vicksburg.

His lightning moves prevented the cooperation of two Confederate armies in Mississippi and

led to eventual surrender of the besieged citadel of Vicksburg in July 1863. Grant's victory virtually opened the river and bisected the Confederacy.

A smashing victory against Gen. Braxton Bragg at Chattanooga in November 1863 firmly established

his reputation as the Union's finest commander. See also Mississippi Civil War History Homepage.

From his assumption of command 7 months before, Pemberton had put his engineers

to work constructing a fortified line which would protect Vicksburg against an attack from the rear. A strong line of works

had been thrown up along the crest of a ridge which was fronted by a deep ravine. The defense line began on the river 2 miles

above Vicksburg and curved for 9 miles along the ridge to the river below, thus enclosing the city within its arc. So long

as this line could be held, the river batteries denied to the North control of the Mississippi River.

| Union artillery target the Vicksburg fortification |

|

| Union artillery target the Confederate fortification |

At salient and commanding points along the line, artillery positions

and forts (lunettes, redans, and redoubts) had been constructed. The earth walls of the forts were up to 20-feet thick, and

from the ditch to the top of the salient was also nearly 20-feet. In front of these was dug a deep, wide ditch that was often

laced with mines. The assaulting troops which climbed the steep ridge slope and reached the ditch would still have a high

vertical wall to climb in order to gain entrance into the fort. Between the strong points, which were located every few hundred