|

"Cumberland Gap" in the American

Civil War

General Ulysses S. Grant,

while traveling through the Cumberland Gap in 1864, noted: "With two brigades of the Army of the Cumberland I could hold

that pass against the army which Napoleon led to Moscow."

Introduction

General Grant knew

the importance of securing the Cumberland Gap during the Civil War, having resided in neighboring states for most of

his life he was also familiar with its strategic history. The Army of the Cumberland, a Union army, was also named for

the region. As a direct result of Confederate Gen. John W. Frazer surrendering his command without any attempts of fighting

the enemy or evading capture, 44% of the 62nd North Carolina's soldiers died within

18 months of their incarceration in a single Union prison.

Major B. G. McDowell, 62nd North

Carolina, stated that "When I was told by General Frazer that I had been surrendered, and that I and my regiment were prisoners

of war my indignation and that of my regiment knew no bounds. I informed him that I would not be made a prisoner of war that

it took two to make such a bargain as that under the circumstances, and that he could not force me to do so. Sharp words were

exchanged, and I called up all of the Sixty-second Regiment who were willing to take their lives in their hands and all of

the other commands in the Gap who were willing to join us, and said to them, "If you will go with me we will go out from

here, and let consequences take care of themselves."

In late December 1862, while guarding bridges and railroads in East Tennessee,

three poorly armed companies (295 soldiers) of the 62nd North Carolina

Regiment were captured by a Union cavalry force of 3,000. The 62nd continued to serve and fight in East Tennessee until 442 of its men were surrendered

to Union forces in the Cumberland Gap on September 9, 1863, by General Frazer, who many consider a coward for not fighting

nor trying to evade capture, but as many as 200 soldiers from the 62nd evaded capture and in April 1864 the unit mustered

178 men in Asheville. The bulk of the fighting at the Battle of Asheville one year later, April 6, 1865, and just three days prior to Lee surrendering to

Grant, was shouldered by the remaining 175 steadfast warriors who formed the ranks of the depleted unit for its

final mustering.

| Cumberland Gap and the Civil War |

|

| The Majestic Cumberland Gap and the Civil War |

Confederate General John W. Frazer surrenders

the Cumberland Gap

Frazer

believed that he was outnumbered by Union Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's army by a margin of at least 5-to-1. Frazer, however,

refused to obey orders to "fight or retreat." Since hundreds of Confederates under Frazer's command evaded capture in

the Cumberland Gap, it is fair to say that Frazer could have, at the very least, evaded

capture.

…Lining up along the Harlan

Road, the Confederates were amazed to see the small

force to which they had surrendered…

General Frazer was a West Point Graduate, New Yorker, and Union Army General John Buford

contemporary. According to the Official Records of Union

and Confederate Armies (hereinafter cited as O.R.), General Frazer had the opportunity to fight, retreat, or evacuate

from the Cumberland Gap and save his command from a "long imprisonment and death." According to several Confederate officers, Frazer

displayed "treachery and cowardice which led to the unconditional surrender of the strongest natural position in the Confederate

States." And with it, "2,026 prisoners, 2,000 small arms, 12 pieces of artillery, and the stores of ammunition and provision.

They also surrendered 200 horses and mules, 50 wagons, 160 cattle, 12,000 pounds of bacon, 2000 bushels of wheat, and approximately 15,000 pounds of flour."

According to the Official Records, on September 9, 1863, General Frazer was credited

for surrendering 2,026 soldiers (including the Sixty-second and Sixty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiments) defending the Cumberland Gap. Some believed that Frazer was "bribed to surrender" the Gap. Major,

later Lt. Col., Byron Gibbs McDowell was the only 62nd North Carolina Regimental field officer present during the surrender of the Cumberland Gap. During

the surrender, Commanding Colonel Love was ill and not present and Lt. Col. Clayton had contracted typhoid fever and was in

a hospital in Greenville, Tennessee. In O.R., I, 30, II, pp. 636-637, McDowell discusses the Cumberland Gap's surrender and exclaims

that Frazer's report is "slanderous." Jefferson Davis endorses the report by writing that Frazier's surrender "presents

a shameful abandonment of duty."

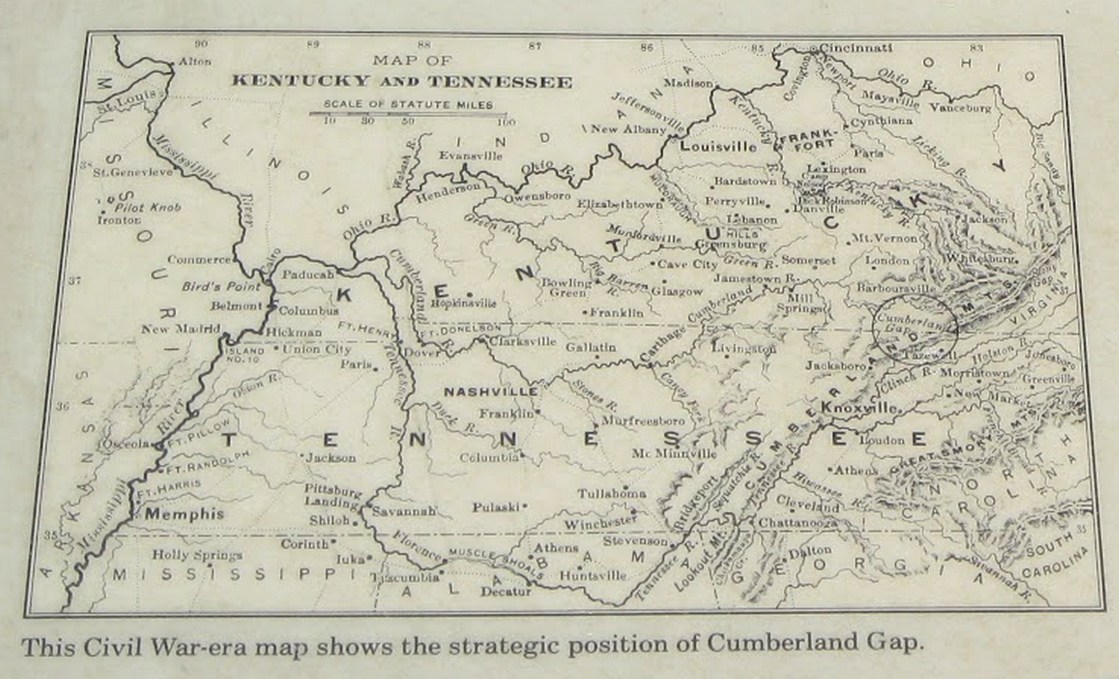

| Map of Cumberland Gap during the Civil War |

|

| Civil War Map of Cumberland Gap and its proximity to adjoining regions and states |

| Battle of the Cumberland Gap |

|

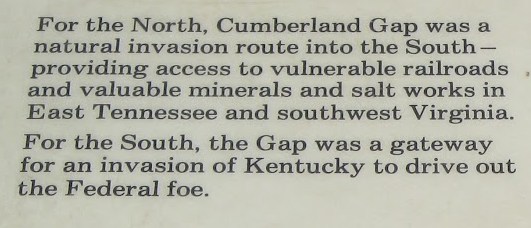

| Why was the Cumberland Gap important during the Civil War? |

Sequential official correspondence

with General John Wesley Frazer

Below are excerpts from the Official

Records: O.R., I,

30, II, 602, O.R., I,

30, IV, 571, O.R., I,

30, IV, p. 572, O.R., I,

30, II, p. 617, O.R., I,

30, II, p. 624, O.R.,

I, 30, II, pp. 629-639, and O.R., I, 30, II, pp. 607-615. Also, for its entirety, see General

John Frazer's comments regarding why he surrendered the Cumberland Gap, and Lt. Colonel B. G. McDowell's official report for

the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies in O.R., I, 30, II, pp. 607-639

KNOXVILLE AUGUST 21, 1863 (RECEIVED 22ND)

…. My orders

to General Frazer are to defend Cumberland Gap to last.

S. B. BUCKNER

Major-General

KNOXVILLE,

AUGUST 21, 1863

The 65th

Georgia is ordered to reinforce you from Jacksborough [Jacksboro]

with the artillery now at Big Creek Gap. You [General Frazer] are expected to hold your position to the last.

V. SHELIHA

Chief of Staff

LOUDON [TN], AUGUST 30, 1863—p. m.

General Frazer received

message and will carry out your order…

General MacKall

Chief of Staff;

Chattanooga

Loudon [TN],

August 30, 1863

Brigadier-General Frazer

Cumberland

Gap:

You overrate [General]

Burnside’s forces…

V. SHELIHA

Chief of Staff

Loudon [TN],

August 30, 1863

General J. W. Frazer

Commanding Cumberland

Gap:

Hold the Gap according

to my first instructions a week ago…

S. B. BUCKNER

Major-General

Loudon [TN],

August 30, 1863

Brigadier-General Frazer

Cumberland

Gap:

Evacuate your position

at once….notifying Major-General [Sam] Jones of the move. Destroy all stores for which you cannot find transportation.

V. SHELIHA

Chief of Staff

General Frazer:

Evacuate all your forces

as speedily as possible…retire [retreat] to Abington [Abingdon, Virginia,

Cumberland area]. Report your movements by courier and telegraph to General Jones.

S.

B. BUCKNER

Major-General

(Duplicate of above

sent to General A. E. Jackson, Jonesborough, Tenn.)

Maj. Gen. S. Jones

CHATTANOOGA, TENN.

Dublin,

Va.:

September 6, 1863

Send an order to General

Frazer, at Cumberland Gap, to evacuate the gap…

S.

B. BUCKNER

Major-General

Brig. Gen. John S. Williams, Abington [VA], September 11, 1863

Commanding, &.,

Jonesborough:

GENERAL: Since writing

to you this morning I received a dispatch… General Frazer and Cumberland Gap capitulated…

I hope that the report is not true…

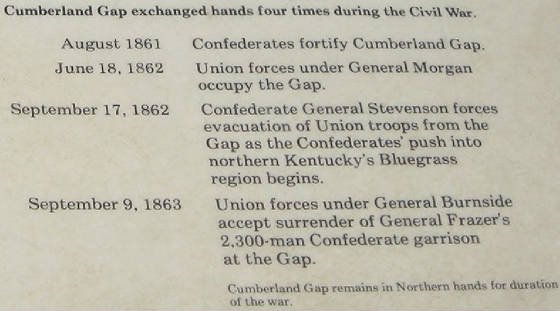

| Civil War Battles for control of Cumberland Gap |

|

| One must travel through the Cumberland Gap - or spend weeks going around it |

Colonel

B. G. McDowell

By 12 o’clock

on September 9, 1863, Union officers had already sent four letters to General

Frazer "demanding surrender of the Commanding Confederate forces of the Cumberland Gap." Frazer

inquired of Burnside, “To what is the strength of your army?” Burnside declared, “I can not tell, surrender.”

Major (his rank at

the time) McDowell insisted, "We want to fight! We waited and waited! Then at 4 p.m. we were informed that we were prisoners

of war."

McDowell (a native

of Macon County, N.C.) and about 600 soldiers refused to surrender, and they evaded capture, reformed in Asheville, N.C.,

and fought until the bitter end of the Civil War.

General John W. Frazer

According to Official

Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Brigadier General John W. Frazer stated the most treacherous and slanderous remarks

about the 62nd North Carolina Regiment: "The discipline and organization were utterly worthless… the

greater part of officers were totally unfitted for command…Colonel Love and Major McDowell, I do not think were qualified

for command…My opinion is this regiment would have broken or thrown down their arms on the first fire from the enemy…There

were numerous desertions…In fact not a week passed without several desertions…We had insufficient arms to fight...I

believed we were greatly outnumbered...I was unsure of the enemy's strength...I thought surrender would save lives...General

Buckner was no where to be found, I wondered what became of him..."

General Frazer died March 31, 1906, in New York, NY.,

and perhaps was not credible with his contradictory remarks about the surrender of the 62nd North Carolina and the Cumberland

Gap. (He underscored his initial contradictory account for the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.) He had ample time to make a retraction or state that he was under duress when he made the

statements. Frazer opined that Union forces numbered 10,000-30,000 under Burnside. Burnside also sent at least four

letters to Frazer demanding surrender and insisted, “We expect your [Frazer] unconditional surrender.”

(O.R., I, 30, II, p. 638 and O.R., I, 30, II, p. 624). General Frazer, moreover, had been ordered to retreat

to a very advantageous position, the high ground; however, he surrendered without a shot. (O.R., I, 30, II, p. 602).

| How to win a battle without firing a shot... |

|

| General Burnside's Union army passing through Cumberland Gap in September 1863, Harper's Weekly |

Closing Remarks

Lt. Col. Byron

Gibbs McDowell a coward? Even after being shot while fighting bushwhackers, McDowell fought valiantly and bravely until the

end of the conflict, and he was also recorded on muster rolls and troop rosters in April 1865. McDowell was a leader

and inspiration to the men who served in his command and he was quick to lead by example. The men who evaded capture,

of their own free will they too fought until the end of the conflict. Their actions were not indicative of cowardice.

Frazer made his blistering remarks while in Union captivity, and, if he was only trying to gain favor while incarcerated,

he could have made a retraction after the war-- but he didn't. Perhaps out of fear for his life, it explains why he

lived his remaining years in New York. Did Frazer sell out as some have suggested? Perhaps. Regardless

of Frazer's motives or excuses, it is evident by the hundreds who had evaded capture, he also could have led many, if

not all, of his command to another position. Frazer was similar to the possum at the Cumberland Gap, and his inaction

and disobedience to orders from his superiors, as well as his lack of leadership, "presents a shameful

abandonment of duty," said Jeff Davis bluntly. There is a lot of truth to that old saying, run away and live to fight another

day. But of the 442 men of the 62nd who were captured in the Cumberland Gap and incarcerated in Union prisons, 44% died. Nearly 750 of the regiment's 1,000 had been captured during the war,

but the remaining 175 who formed the shattered unit were present for the daring defense of Asheville on April 6, 1865.

(See related reading below.)

Recommended

Reading: To

Die in Chicago: Confederate Prisoners at Camp Douglas 1862-65 (Hardcover: 446 pages). Description: The author’s research is exacting, methodical, and painstaking. He brought zero bias to the enterprise and the

result is a stunning achievement that is both scholarly and readable. Douglas, the "accidental" prison camp, began as a training

camp for Illinois volunteers. Donalson and Island #10 changed that.

The long war that no one expected… combined with inclement weather – freezing temperatures - primitive medical

care and the barbarity of the captors created in the author’s own words "a death camp." Stanton's and Grant's policy

of halting the prisoner exchange behind the pretense of Fort

Pillow accelerated the suffering. Continued below...

In the latest

edition, Levy found the long lost hospital records at the National Archives which prove conclusively that casualties were

deliberately “under reported.” Prisoners were tortured, brutality was tolerated and corruption was widespread.

The handling of the dead rivals stories of Nazi Germany. The largest mass grave in the Western Hemisphere is filled with....the

bodies of Camp Douglas dead, 4200 known and 1800 unknown.

No one should be allowed to speak of Andersonville until they have absorbed the horror of Douglas, also known as “To

Die in Chicago.”

Recommended

Reading: East

Tennessee and the Civil War (Hardcover: 588 pages). Description:

A solid social, political, and military history, this work gives light to the rise of the pro-Union and pro-Confederacy factions.

It explores the political developments and recounts in fine detail the military maneuvering and conflicts that occurred. Beginning

with a history of the state's first settlers, the author lays a strong foundation for understanding the values and beliefs

of East Tennesseans.

He examines the rise of abolition and secession, and then advances into the Civil War. Continued below...

Early

in the conflict, Union sympathizers burned a number of railroad bridges, resulting in occupation by Confederate troops and

abuses upon the Unionists and their families. The author also documents in detail the ‘siege and relief’ of Knoxville.

Although authored by a Unionist, the work is objective in nature and fair in its treatment of the South and the Confederate

cause, and, complete with a comprehensive index, this work should be in every Civil War library.

Recommended Reading: War at Every Door: Partisan Politics and Guerrilla

Violence in East Tennessee, 1860-1869. Description: One of the most divided regions of the Confederacy, East Tennessee was the site

of fierce Unionist resistance to secession, Confederate rule, and the Southern war effort. It was also the scene of unrelenting

'irregular,' or guerrilla, warfare between Union and Confederate supporters, a conflict that permanently altered the region's

political, economic, and social landscape. In this study, Noel Fisher examines the military and political struggle for control

of East Tennessee from the secession crisis through the early years of Reconstruction, focusing

particularly on the military and political significance of the region's irregular activity. Continued below...

Fisher portrays

in grim detail the brutality and ruthlessness employed not only by partisan bands but also by Confederate and Union troops under constant

threat of guerrilla attack and government officials frustrated by unstinting dissent. He demonstrates that, generally, guerrillas

were neither the romantic, daring figures of Civil War legend nor mere thieves and murderers, but rather were ordinary men

and women who fought to live under a government of their choice and to drive out those who did not share their views.

Recommended Reading: Portals to Hell: Military Prisons

of the Civil War. Description:

The military prisons of the Civil War, which held more than four hundred thousand soldiers and caused the deaths of fifty-six

thousand men, have been nearly forgotten. Lonnie R. Speer has now brought to life the least-known men in the great

struggle between the Union and the Confederacy, using their own words and observations as

they endured a true “hell on earth.” Drawing on scores of previously unpublished firsthand accounts, Portals to

Hell presents the prisoners’ experiences in great detail and from an impartial perspective. The first comprehensive

study of all major prisons of both the North and the South, this chronicle analyzes the many complexities of the relationships

among prisoners, guards, commandants, and government leaders. It is available in paperback and hardcover.

Recommended Viewing: The Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns. Review: The

Civil War - A Film by Ken Burns is the most successful public-television miniseries in American history. The 11-hour Civil War didn't just captivate a nation,

reteaching to us our history in narrative terms; it actually also invented a new film language taken from its creator. When

people describe documentaries using the "Ken Burns approach," its style is understood: voice-over narrators reading letters

and documents dramatically and stating the writer's name at their conclusion, fresh live footage of places juxtaposed with

still images (photographs, paintings, maps, prints), anecdotal interviews, and romantic musical scores taken from the era

he depicts. Continued below...

The Civil War uses all of these devices to evoke atmosphere and resurrect an event that many knew

only from stale history books. While Burns is a historian, a researcher, and a documentarian, he's above all a gifted storyteller,

and it's his narrative powers that give this chronicle its beauty, overwhelming emotion, and devastating horror. Using the

words of old letters, eloquently read by a variety of celebrities, the stories of historians like Shelby Foote and rare, stained

photos, Burns allows us not only to relearn and finally understand our history, but also to feel and experience it. "Hailed

as a film masterpiece and landmark in historical storytelling." "[S]hould be a requirement for every

student."

Surrender of the Cumberland Gap, Civil War Tennessee, Civil War

Battle Cumberland Gap History, Details, Kentucky, North Carolina, Regiments in the Cumberland Gap Battles, General Ambrose

Burnside

|