|

The Life of Vice President John C. Breckinridge

The nominee, John Cabell Breckinridge, was thirty-six years old—just a year over

the constitutional minimum age for holding the office—and his election would make him the youngest vice president in

American history. John Breckinridge was cousin to Mary Todd, wife of Abraham Lincoln.

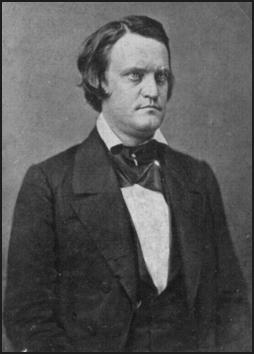

| John C. Breckinridge |

|

| Library of Congress |

An Illustrious Political Family

Born at "Cabell's Dale," the Breckinridge family estate near Lexington, Kentucky,

on January 16, 1821, John Cabell Breckinridge was named for his father and grandfather. The father, Joseph Cabell Breckinridge,

a rising young politician, died at the state capital at the age of thirty-five. Left without resources, his wife took her

children back to Cabell's Dale to live with their grandmother, known affectionately as "Grandma Black Cap." She often regaled

the children with stories of their grandfather, the first John Breckinridge, who, in addition to introducing the Kentucky

Resolutions that denounced the Alien and Sedition Acts, had helped secure the Louisiana Purchase and had served during the administration of Thomas Jefferson--first as a Senate leader and then as attorney general. The

grandfather might well have become president one day but, like his son, he died prematurely. The sense of family mission that

his grandmother imparted shaped young John C. Breckinridge's self-image and directed him towards a life in public office.

The family also believed strongly in education, since Breckinridge's maternal grandfather, Samuel Stanhope Smith, had served

as president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, and his uncle Robert J. Breckinridge started Kentucky's public school

system. The boy attended the Presbyterian Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, where he received his bachelor's degree at

seventeen. He then attended Princeton before returning to Lexington to study law at Transylvania University.

A tall, strikingly handsome young

man with a genial air and a powerful voice, considered by many "a perfect gentleman," Breckinridge set out to make his fortune

on the frontier. In 1841, he and his law partner Thomas W. Bullock settled in the Mississippi River town of Burlingame, in the Iowa Territory. Breckinridge might have entered politics and pursued a career relatively free from the divisive issue of slavery, but Iowa's fierce

winter gave him influenza and made him homesick for Kentucky. When he returned home on a visit in 1843, he met and

soon married Mary Cyrene Burch of Georgetown. The newlyweds settled in Georgetown, and Breckinridge opened a law office in

Lexington.

A Rapid Political Rise

When the Mexican War began, Breckinridge volunteered to serve as an officer in a Kentucky infantry regiment. In Mexico, Major Breckinridge won

the support of his troops for his acts of kindness, being known to give up his horse to sick and footsore soldiers. After

six months in Mexico City, he returned to Kentucky and to an almost inevitable political career. In 1849, while still only

twenty-eight years old, he won a seat in the state house of representatives. In that election, as in all his campaigns, he

demonstrated both an exceptional ability as a stump speaker and a politician's memory for names and faces. Shortly after the

election, he met for the first time the Illinois legislator who had married his cousin Mary Todd. Abraham Lincoln, while visiting his wife's family in Lexington, paid courtesy calls on the city's lawyers. Lincoln and Breckinridge became

friends, despite their differences in party and ideology. Breckinridge was a Jacksonian Democrat in a state that

Senator Henry Clay had made a Whig bastion. In 1851, Breckinridge shocked

the Whig party by winning the congressional race in Clay's home district, a victory that also brought him to the attention

of national Democratic leaders. He arrived in Congress shortly after the passage of Clay's Compromise of 1850, which had sought to settle the issue of slavery in the territories. Breckinridge became a spokesman for the proslavery Democrats,

arguing that the federal government had no right to interfere with slavery anywhere, either in the District of Columbia or

in any of the territories. Breckinridge, moreover, believed that each state should determine its own internal affairs.

Since Breckinridge defended both the Union and slavery, people viewed him

as a moderate. The Pennsylvania newspaper publisher and political adventurer John W. Forney

insisted that when Breckinridge came to Congress "he was in no sense an extremist." Forney recalled how the young Breckinridge

spoke with great respect about Texas Senator Sam Houston, who denounced the dangers and evils of slavery. But Forney thought

that Breckinridge "was too interesting a character to be neglected by the able ultras of the South. They saw in his winning

manners, attractive appearance, and rare talent for public affairs, exactly the elements they needed in their concealed designs

against the country." People noted that his uncle, Robert Breckinridge, was a prominent antislavery man, and that as a state

legislator Breckinridge had aided the Kentucky Colonization Society (a branch of the American Colonization Society), dedicated

to gradual emancipation and the resettlement of free blacks outside the United States. They suspected that he held private

concerns about the morality of slavery and that he supported gradual emancipation. Yet, while Breckinridge was no planter

or large slaveholder, he owned a few household slaves and idealized the Southern way of life. He willingly defended slavery

and white supremacy against all critics.

The Kansas-Nebraska Controversy

In Congress, Breckinridge became an ally of Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas. When Douglas introduced the Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and left the issue of slavery in the territories to the settlers themselves—a policy known as "Popular Sovereignty"—Breckinridge worked hard to enact the legislation. Going to the White House, he served as a broker between Douglas

and President Franklin Pierce, persuading the president to support the bill. He also spoke in the House in favor of leaving

the settlers "free to form their own institutions, and enter the Union with or without slavery, as their constitutions should

prescribe."

During those debates in March 1854, the normally even-tempered Breckinridge

exchanged angry words on the House floor with Democratic Representative Francis B. Cutting of New York, almost provoking a

duel. "They were a high-strung pair," commented Breckinridge's friend Forney. Cutting accused Breckinridge of ingratitude

toward the North, where he had raised campaign funds for his tough reelection campaign in 1853. Breckinridge, "his eyes flashing

fire," interrupted Cutting's speech, denied his charges, denounced his language, and demanded an apology. When Cutting refused,

Breckinridge interpreted this as a challenge to a duel. He proposed that they meet near Silver Spring, the nearby Maryland

home of his friend Francis P. Blair, and that they duel with western rifles. The New Yorker objected that he had never handled

a western rifle and that as the challenged party he should pick the weapons. Once it became clear that neither party considered

himself the challenger, they gained a face-saving means of withdrawing from the "code of honor" without fighting the duel.

When the two next encountered each other in the House, Breckinridge looked his adversary in the eye and said: "Cutting, give

me a chew of tobacco!" The New Yorker drew a plug of tobacco from his pocket, cut off a wad for Breckinridge and another for

himself, and both returned to their desks chewing and looking happier. Those who observed the exchange compared it to the

American Indians' practice of smoking a peace pipe.

Breckinridge supported the Kansas-Nebraska Act in the hope that it would take

slavery in the territories out of national politics, but the act had entirely the opposite effect. Public outrage throughout

the North caused the Whig party to collapse and new antislavery parties, the Republican and the American (Know-Nothing) parties,

to rise in its wake. When the spread of Know-Nothing lodges in his district jeopardized his chances of reelection in 1855,

Breckinridge declined to run for a third term. He also rejected President Pierce's nomination to serve as minister to Spain

and negotiate American annexation of Cuba, despite the Senate's confirmation of his appointment. Citing his wife's poor health

and his own precarious finances, Breckinridge returned to Kentucky. Land speculation in the West helped him accumulate a considerable

amount of money during his absence from politics.

The Youngest Vice President

As the Democratic convention approached in 1856, the three leading contenders—President

Pierce, Senator Douglas, and former Minister to Great Britain James Buchanan—all courted Breckinridge. He attended the

convention as a delegate, voting first for Pierce and then switching to Douglas. When Douglas withdrew as a gesture toward

party unity, the nomination went to Buchanan. The Kentucky delegation nominated former House Speaker Linn Boyd for vice president.

Then a Louisiana delegate nominated Breckinridge. Gaining the floor, Breckinridge declined to run against his delegation's

nominee, but his speech deeply impressed the convention. One Arkansas delegate admired "his manner, his severely simple style

of delivery with scarcely an ornament [or] gesture and deriving its force and eloquence solely from the remarkably choice

ready flow of words, the rich voice and intonation." The delegate noted that "every member seemed riveted to his seat and

each face seemed by magnetic influence to be directed to him." When Boyd ran poorly on the first ballot, the convention switched

to Breckinridge and nominated him on the second ballot. Although Tennessee's Governor

Andrew Johnson grumbled that Breckinridge's lack of national reputation would hurt the

ticket, Buchanan's managers were pleased with the choice. They thought Breckinridge would appease Douglas, since the

two men had been closely identified through their work on the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Being present at the convention, Breckinridge

was prevailed upon to make a short acceptance speech, thanking the delegates for the nomination, endorsing Buchanan and the

platform, and reaffirming his position as a "state's rights man." The nominee was thirty-six years old—just a year over

the constitutional minimum age for holding the office—and his election would make him the youngest vice president in

American history.

Breckinridge spent most of the campaign in Kentucky, but he gave speeches

in Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan, defending the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The election was a three-way race among the Democrats under

Buchanan, the Republicans under John Charles Frémont, and the Know-Nothings under former

President Millard Fillmore. Denouncing the antislavery policies of the Republicans and Know-Nothings, Breckinridge described

himself not as proslavery but as a defender of the people's constitutional right (See: United States Constitution) to make their own territorial laws, a position that caused some Deep

South extremists to accuse him of harboring abolitionist views. In November, Democrats carried all the slaveholding states except Maryland (which went Know-Nothing) and enough Northern

states to win the election. Breckinridge was proud that Kentucky voted for a Democratic presidential ticket for the first

time since 1828.

Strained Relations with Buchanan

Buchanan won the nomination and election primarily because nobody knew

where he stood on the issues, since he had been out of the country for the past three years as minister to England. Although

his supporters promoted him as "the man for the crisis," Buchanan was in fact the worst man for the crisis.

Narrow, secretive, petty, vindictive, and blind to corruption within his administration, he proved unable to bind together

either the factions of his party or the regions of his nation. A poor winner, Buchanan distrusted

his rivals for the nomination and refused to invite Stephen Douglas to join his cabinet or to take seriously Douglas'

patronage requests. Similarly snubbed, Breckinridge quickly discovered that he held less influence with Buchanan as vice president

than he had as a member of the House with Pierce.

Viewing Breckinridge as part of the Pierce-Douglas faction, Buchanan almost

never consulted him, and rarely invited him to the White House for either political or social gatherings. Early in the new

administration, when the vice president asked for a private interview with the president, he was told instead to call at the

White House some evening and ask to see Buchanan's niece and hostess, Harriet Lane. Taking this as a rebuff, the proud Kentuckian

left town without calling on either Miss Lane or the president. His friends reported his resentment to Buchanan, and in short

order three of the president's confidants wrote to tell Breckinridge that it had been a mistake. A request to see Miss Lane

was really a password to admit a caller to see her uncle. How Breckinridge could have known this, they did not explain. In

fact, the vice president had no private meetings with the president for over three years.

The new vice president bought property in the District of Columbia and

planned to construct, along with his good friends Senator Douglas and Senator Henry Rice of Minnesota, three large, expensive,

connected houses at New Jersey Avenue and I Street that would become known as "Minnesota Row." Before the construction was

completed, however, the friendship had become deeply strained when Douglas fell out with President Buchanan over slavery in

Kansas. A proslavery minority there had sent to Washington a new territorial constitution—known as the Lecompton

Constitution. Buchanan threw his weight behind the Lecompton Constitution as a device for admitting Kansas as a state and

defusing the explosive issue of slavery in the territory. But Douglas objected that

the Lecompton Constitution made a mockery out of popular sovereignty and warned that he would fight it as a fraud. Recalling

the way Andrew Jackson had dealt with his opponents, Buchanan said, "Mr. Douglas, I desire you

to remember that no Democrat ever yet differed from an Administration of his choice without being crushed." To which

Douglas replied, "Mr. President, I wish you to remember that General Jackson is dead." Between these two poles, the vice president

vainly sought to steer a neutral course. He sided with Buchanan on the Lecompton Constitution but endorsed Douglas for reelection

to the Senate.

An Impartial Presiding Officer

As vice president in such a turbulent era, Breckinridge won respect for presiding

gracefully and impartially over the Senate. On January 4, 1859, when the Senate met for the last time in its old chamber,

he used the occasion to deliver an eloquent appeal for national unity. During its half century in the chamber, the Senate

had grown from thirty-two to sixty-four members. The expansion of the nation forced them to move to a new, more spacious chamber.

During those years, he observed, the Constitution had "survived peace and war, prosperity and adversity" to protect "the larger

personal freedom compatible with public order." He recalled the legislative labors of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John

C. Calhoun, whose performance in that chamber challenged their successors "to give the Union a destiny not unworthy of the

past." He trusted that in the future "another Senate, in another age, shall bear to a new and larger Chamber, this Constitution

vigorous and inviolate, and that the last generation of posterity shall witness the deliberations of the Representatives of

American States, still united, prosperous, and free." The vice president then led a procession to the new chamber. Walking

two-by-two behind him were the political and military leaders of what would soon become the Union and the Confederacy.

Breckinridge counseled against secession. A famous incident, recounted in many memoirs of the era, took place at a dinner party that the vice president attended.

South Carolina Representative Lawrence Keitt repeatedly denigrated Kentucky's compromising tendencies. Breckinridge responded

by recalling a trip he had made through South Carolina, where he met a militia officer in full military regalia. "I tell you,

sah, we can not stand it any longer; we intend to fight," said the officer. "And from what are you suffering?" asked Breckinridge.

"Why, sah, we are suffering from the oppression of the Federal Government. We have suffered under it for thirty years, and

will stand it no more." Turning to Keitt, Breckinridge advised him "to invite some of his constituents, before undertaking

the war, upon a tour through the North, if only for the purpose of teaching them what an almighty big country they will have

to whip before they get through!"

A Four-Way Race for President

Early in 1859 a New York Times correspondent in Washington wrote that

"Vice President Breckinridge stands deservedly high in public estimation, and has the character of a man slow to form resolves,

but unceasing and inexorable in their fulfillment." At a time when the Buchanan administration was falling "in prestige and

political consequence, the star of the Vice President rises higher above the clouds." Later that year, Linn Boyd died while

campaigning for the Senate, and Kentucky Democrats nominated Breckinridge for the seat, which would become vacant at the time

Breckinridge's term as vice president ended. Breckinridge may also have been harboring even greater ambitions. Although he

remained silent about the upcoming presidential campaign, many Democrats considered him a strong contender. In 1860, the Democratic

convention met in Charleston, South Carolina. Stephen Douglas was the frontrunner, but when his supporters defeated efforts

to write into the platform a plank protecting the right of slavery anywhere in the territories, the Southern delegates walked

out. They held their own convention in Baltimore and nominated Breckinridge as their presidential candidate.

For national balance, the breakaway Democrats selected Senator Joseph Lane,

a Democrat from Oregon, for vice president. Lane had spent his youth in Kentucky and Indiana and served in the Mexican War.

President James K. Polk had appointed him territorial governor of Oregon, an office he held from 1849 to 1850 before becoming

Oregon's territorial delegate to Congress in 1851. When Oregon entered the Union in 1859, he was chosen one of its first senators.

Lane's embrace of the secessionist spirit attracted him to the Southern Democrats. Had the four-way election of 1860 not been

decided by the electoral college but been thrown into Congress, the Democratic majority in the outgoing Senate might well

have elected him vice president. Instead, the race ended Lane's political career entirely, and Oregon became a Republican

state.

Breckinridge faced a campaign against three old friends: Stephen Douglas,

the Democratic candidate; Abraham Lincoln, the Republican; and John Bell of Tennessee, the Constitutional Union party candidate.

He was not optimistic about his chances. Privately, he told Mrs. Jefferson Davis, "I trust that I have the courage to lead

a forlorn hope." At a dinner just before the nomination, Breckinridge talked of not accepting it, but Jefferson Davis persuaded

him to run. Worried that a split in the anti-Republican vote would ensure Lincoln's victory, Davis proposed a scheme by which

Breckinridge, Douglas, and Bell would agree to withdraw their candidacies in favor of a compromise candidate. Breckinridge

and Bell agreed, but Douglas refused, arguing that Northern Democrats would take Lincoln before they voted for any candidate

that the Southern firebrands had endorsed. The Illinois senator pointed out that, while not all of Breckinridge's followers

were secessionists, every secessionist was supporting him. But Breckinridge also counted on the support of the last three

Democratic presidential candidates, Lewis Cass, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan, as well as most of the Northern Democratic

senators and representatives. Despite these endorsements and the financial levies that the Buchanan administration made on

all Democratic officeholders for him, Breckinridge failed to carry any Northern states. In the four-way race, he placed third

in the popular vote and second in electoral votes. Most disappointingly, he lost Kentucky to Bell.

A Personal Secession

Following the election, Breckinridge returned to Washington to preside over

the Senate, hoping to persuade Southerners to abandon secession. But in December, South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and

Florida left the Union. In January, Mississippi Senator Jefferson Davis and other Southerners bid a formal farewell to the

Senate. In February, Vice President Breckinridge led a procession of senators to the House chamber to count the electoral

votes, and to announce the election of Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. On March 4, Breckinridge administered the oath of office

to his successor, Hannibal Hamlin, who in turn swore him into the Senate.

When President Lincoln called Congress into special session on July 4, 1861, to raise the arms and men necessary to fight

the Civil War, Breckinridge returned to Washington as the leader of what was left of the Senate Democrats. Many in Washington

doubted that he planned to offer much support to the Union or the war effort. Breckinridge seemed out of place in the wartime

capital, after so many of his Southern friends had left. On several occasions, however, he visited his cousin Mary Todd Lincoln

at the White House.

During the special session, which lasted until August 6, 1861, Breckinridge

remained firm in his belief that the Constitution strictly limited the powers of the federal government, regardless of secession

and war. Although he wanted the Union restored, he preferred a peaceful separation rather than "endless, aimless, devastating

war, at the end of which I see the grave of public liberty and of personal freedom." The most dramatic moment of the session

occurred on August 1, when Senator Breckinridge took the floor to oppose the Lincoln administration's expansion of martial

law. As he spoke, Oregon Republican Senator Edward D. Baker entered the chamber, dressed in the blue coat of a Union army

colonel. Baker had raised and was training a militia unit known as the California Regiment. When Breckinridge finished, Baker

challenged him: "These speeches of his, sown broadcast over the land, what meaning have they? Are they not intended for disorganization

in our very midst?" Baker demanded. "Sir, are they not words of brilliant, polished treason, even in the very Capitol?" Within

months of this exchange, Senator Baker

was killed while leading his militia at the Battle of Ball's Bluff along the Potomac River, and Senator Breckinridge was wearing

the gray uniform of a Confederate officer. (See also General John Cabell Breckinridge.)

After the special session, Breckinridge

returned to Kentucky to try to keep his state neutral. He spoke at a number of peace rallies, proclaiming that, if Kentucky

took up arms against the Confederacy, then someone else must represent the state in the Senate. Despite his efforts,

pro-Union forces won the state legislative elections. When another large peace rally was scheduled for September 21, the legislature

sent a regiment to break up the meeting and arrest Breckinridge. Forewarned, he packed his bag and fled to Virginia. He could

no longer find any neutral ground to stand upon, no way to endorse both the Union and the Southern way of life. Forced to

choose sides, Breckinridge joined his friends in the Confederacy. In Richmond, he volunteered for military service, exchanging,

as he said, his "term of six years in the Senate of the United States for the musket of a soldier." On December 4, 1861, the

Senate by a 36 to 0 vote expelled the Kentucky senator, declaring that Breckinridge, "the traitor," had "joined the enemies

of his country."

Recommended Reading: Breckinridge:

Statesman, Soldier, Symbol (Southern Biography Series) (Paperback, 688 pages). Description: William

C. Davis has written the only full-length biography of John C. Breckinridge, who is one of the most fascinating and yet one

of the least known figures in all of American history. Davis begins by charting Breckinridge's early years as a lawyer, his rise in Kentucky state politics and then national politics, his role as Vice-President

and his reluctant campaign for the Presidency in 1860. Davis

then provides an excellent overview of Breckinridge's career as a Confederate military leader, fighting on nearly every front

of the war and ending the war as the Confederate Secretary of State. Continued below...

Davis also gives an outstanding account of Breckinridge's dramatic escape from the country following the

Confederate defeat, which was an adventure so extraordinary that it should be made into a movie. Davis concludes his work by describing

Breckinridge's years as an exile before his final return to Kentucky

and his tragic early death. Davis is one of the nation’s

most respected Civil War historians, and this book is an excellent manifestation of his scholarly and literary gifts. Not

only is it full of information, allowing the reader to truly feel as though they have a solid understanding of Breckinridge's

life, but it is written in such a fine style that it is always entertaining and never dull.

Recommended

Reading: Generals in Gray: Lives of

the Confederate Commanders. Description: When Generals in Gray was published in 1959, scholars and critics

immediately hailed it as one of the few indispensable books on the American Civil War. Historian Stanley Horn, for example,

wrote, "It is difficult for a reviewer to restrain his enthusiasm in recommending a monumental book of this high quality and

value." Here at last is the paperback edition of Ezra J. Warner’s magnum opus with its concise, detailed biographical sketches and—in an amazing feat of research—photographs of all 425 Confederate generals. Continued below...

The only exhaustive

guide to the South’s command, Generals in Gray belongs on the shelf of anyone interested in the Civil War. RATED 5 STARS!

Recommended

Reading:

Civil War High Commands (1040 pages) (Hardcover). Description: Based on nearly five decades

of research, this magisterial work is a biographical register and analysis of the people who most directly influenced the

course of the Civil War, its high commanders. Numbering 3,396, they include the presidents and their cabinet members, state

governors, general officers of the Union and Confederate armies (regular, provisional, volunteers,

and militia), and admirals and commodores of the two navies. Civil War High Commands will become a cornerstone reference

work on these personalities and the meaning of their commands, and on the Civil War itself. Errors of fact and interpretation

concerning the high commanders are legion in the Civil War literature, in reference works as well as in narrative accounts.

Continued below...

The present

work brings together for the first time in one volume the most reliable facts available, drawn from more than 1,000 sources

and including the most recent research. The biographical entries include complete names, birthplaces, important relatives,

education, vocations, publications, military grades, wartime assignments, wounds, captures, exchanges, paroles, honors, and

place of death and interment. In addition to its main component, the biographies, the volume also includes a number of essays,

tables, and synopses designed to clarify previously obscure matters such as the definition of grades and ranks; the difference

between commissions in regular, provisional, volunteer, and militia services; the chronology of military laws and executive

decisions before, during, and after the war; and the geographical breakdown of command structures. The book is illustrated

with 84 new diagrams of all the insignias used throughout the war and with 129 portraits of the most important high commanders.

Recommended Reading:

Generals in Bronze: Interviewing the Commanders of the Civil War (Hardcover).

Description: Generals in Bronze: Revealing interviews with the commanders of the Civil War. In the decades that followed the

American Civil War, Artist James E. Kelly (1855-1933) conducted in-depth interviews with over forty Union Generals in an effort

to accurately portray them in their greatest moment of glory. Kelly explained: "I had always felt a great lack of certain

personal details. I made up my mind to ask from living officers every question I would have asked Washington or his generals

had they posed for me, such as: What they considered the principal incidents in their career and particulars about costumes

and surroundings." Continued below…

During one interview session with

Gen. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, Kelly asked about the charge at Fort Damnation.

Gen. Chamberlain acquiesced, but then added, "I don't see how you can show this in a picture." "Just tell me the facts," Kelly

responded, "and I'll attend to the picture." And by recording those stirring facts, Kelly left us not only his wonderful art,

but a truly unique picture of the lives of the great figures of the American Civil War. About the Author: William B. Styple

has edited, co-authored, and authored several works on the Civil War. His book: "The Little Bugler" won the Young Readers'

Award from the Civil War Round Table of New York. He is currently writing the biography of Gen. Phil Kearny.

Recommended Reading: Staff Officers in Gray: A Biographical Register of the Staff Officers in the Army of Northern Virginia (Hardcover) (360 pages) (The University of North Carolina Press) (September 3, 2008). Description: This indispensable Civil War reference profiles 2,300 staff officers

in Robert E. Lee's famous Army of Northern Virginia. A typical entry

includes the officer's full name, the date and place of his birth and death, details of his education and occupation, and

a synopsis of his military record. Continued below...

Two appendixes

provide a list of more than 3,000 staff officers who served in other armies of the Confederacy and complete rosters of known

staff officers of each general in the Army of Northern Virginia.

|