|

Mexican-American War Battles and Timeline History

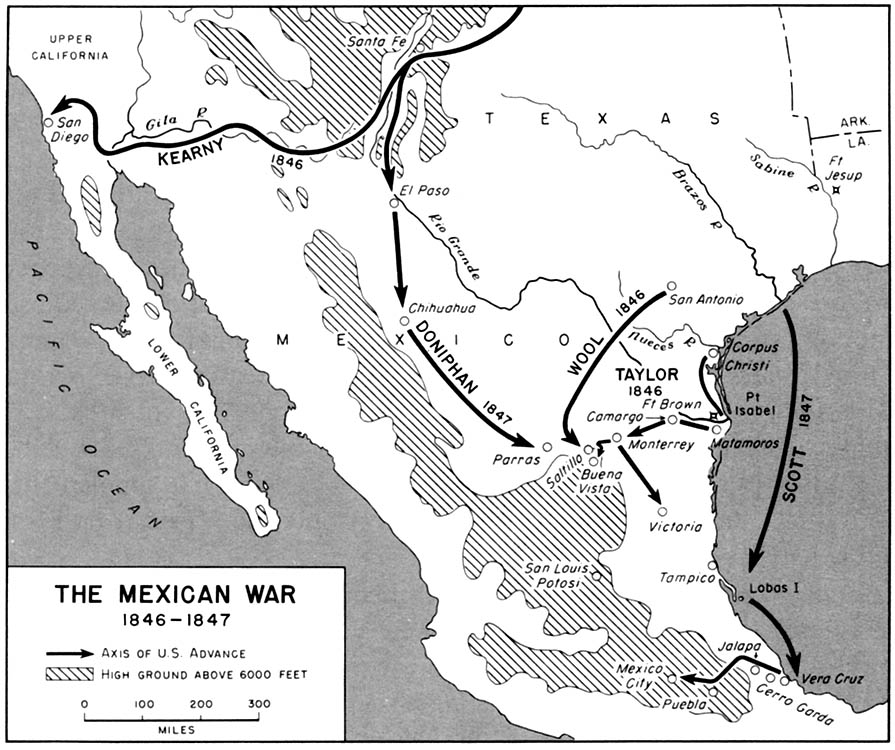

| Mexican-American War Map |

|

| Mexican-American War Battle Map Timeline |

Palo Alto, 8 May 1846. Conditions had been steadily

worsening along the Rio Grande. The United States claimed the Rio Grande as the international border while the Mexican Government

claimed the Nueces as the proper border. Early in 1846, General Zachary Taylor built a fort on the Rio Grande opposite the Mexican town of Matamoros. In April,

the Mexicans countered by sending a force of approximately 1600 cavalrymen across the Rio Grande where, on 25 April,

they overwhelmed a force of 60 dragoons under Captain S. B. Thornton.

Mexican forces at Matamoros had increased by April. By the end of that month,

General Taylor had become concerned about his lines of communication with his lightly held main base at Point Isabel, near

the mouth of the Rio Grande. Therefore, on 1 May, Taylor moved the bulk of his army to Point Isabel, leaving a small detachment

of artillery and infantry under Maj. Jacob Brown at the fort opposite Matamoros. The Mexicans soon placed this fort (later

named Fort Brown) under heavy attack. On 7 May, Taylor advanced toward the fort with about 2,300 men. On the morning of 8

May, about half the distance to the fort, the Americans engaged the enemy, an estimated force of 6,000 men commanded

by Gen. Mariano Arista. (Its right flank rested on an elevation known as Palo Alto; which the engagement was named.) Taylor

moved unhesitatingly into battle, using his artillery to cover the deployment of the infantry. The engagement continued until

nightfall, when the Mexicans withdrew. Effective use of artillery fire was largely responsible for the American victory. American

losses were 9 killed and 47 wounded. The Mexicans suffered more than 700 casualties, including an estimated 320 killed.

Resaca de la Palma, 9 May 1846. The next morning, Taylor,

continuing his advance, found the Mexicans a few miles down the road, where they had taken up a strong defensive position

in a dry river bed known as the Resaca de la Palma. In this second successive day of battle, the infantry conducted most of

the action, although the dragoons played an important role by engaging and defeating the enemy artillery. Eventually the infantry

turned the enemy's left flank, and the Mexican line broke and fled. The rout became a race for the Rio Grande which the Mexicans

won, but many were drowned while attempting to cross the river. Taylor's losses were 33 killed and 89 wounded. Arista's official

report listed 160 Mexicans killed, 228 wounded, and 159 missing. The Americans, however, estimated that the Mexicans

had suffered well over a thousand casualties.

Taylor had to wait until 18 May for boats to move his army across the Rio

Grande. When the Americans finally moved into Matamoros, they found that the Mexican force had disappeared into the interior.

The next objective was Monterey, but the direct overland route from Matamoros lacked water and forage; Taylor therefore waited

until August for the arrival of steamboats, with which he transported his army 130 miles upriver to Camargo. Meanwhile, thousands

of volunteers had poured into Matamoros, but disease and various security and logistic factors limited Taylor to a force of

little more than 6,000 men for the Monterey campaign.

Mexican-American War Timeline of Battles.

| Mexican American War Map of Battlefields |

|

| Mexican American War Battle Map |

| Palo Alto |

8 May 1846 |

| Resaca de la Palma |

9 May 1846 |

| Monterey |

21 September 1846 |

| Buena Vista |

22-23 February 1847 |

| Vera Cruz |

9-29 March 1847 |

| Cerro Gordo |

17 April 1847 |

| Contreras |

18-20 August 1847 |

| Churubusco |

20 August 1847 |

| Molino del Rey |

8 September 1847 |

| Chapultepec |

13 September 1847 |

Monterey, 21 September 1846. Taylor's forces left Camargo

at the end of August and launched an attack on Monterey on 21 September 1846. The city was defended by a force of 7,300

to 9,000 Mexican troops under the command of Gen. Pedro de Ampudia. After three days of hard fighting, the Americans drove

the enemy from the streets to the central plaza. On 24 September, Ampudia offered to surrender the city on the condition that

his troops be allowed to withdraw unimpeded and that an eight-week armistice go into effect. Taylor, believing that

his mission was simply to hold northern Mexico, accepted the terms and the Mexican troops evacuated the city the following

day. Ampudia reported that his army had suffered 367 casualties in the three-day fight. Taylor reported his losses as being

120 killed and 368 wounded. Both reports were probably underestimates.

Taylor was severely criticized in Washington for agreeing to the Mexican terms,

and the Administration promptly repudiated the armistice, which had almost expired by the time the news reached Monterey.

Meanwhile, in keeping with the strategic plan, the other two prongs advanced

into northern Mexico and were ordered into action. On 5 June 1846, Brig. Gen. John E. Wool had left San Antonio with his "Army

of the Center," a force of 2,000 men. His original objective was Chihuahua, but en route it was changed to Parras. Wool,

encountering no opposition, arrived at Parras on 5 December; his force then became part of Taylor's command. The third prong,

Col. (later Maj. Gen.) Stephen W. Kearny's "Army of the West," a force of about 1,660 men, left Fort Leavenworth early in

June 1846 and entered Santa Fe unopposed on 18 August. From there, Kearny left for California on 25 September with about 300

dragoons. En route, he met a party, led by Kit Carson, bringing news from the west coast that a naval squadron under Commodore

J. D. Sloat--with the questionable help of volunteers under Capt. John C. Fremont--had won peaceful possession of California

in July; although some opposition remained. Kearny sent back 200 of his men and pushed on with the rest, arriving at San Diego

on 12 December after having fought a sharp engagement on 6 December against a larger force of Californians at San Pasqual.

At San Diego, Kearny joined Commodore Robert F. Stockton (who had replaced Sloat), and their combined force of about

600 men, after same minor skirmishing, occupied Los Angeles on 10 January 1847. Three days later the last remaining Californian

opposition capitulated to the volunteer force commanded by Fremont.

Meanwhile, in mid-November of 1846, Taylor had ordered one of his divisions

to occupy the city of Saltillo. Another detachment occupied Victoria, a provincial capital between Monterey and the port or

Tampico, which had been occupied by an American naval force under Comdr. David Conner on 15 November 1846. Thus, by the

end of 1846, a very large part of northern Mexico had come under American control.

A plan was adopted late in 1846 to strike at Mexico City by way of Vera Cruz.

In preparation for this expedition, General Winfield Scott, Commanding General of the Army, detached about 8,000 men from Taylor 'a command

early in 1847, ordering the troops to Gulf ports to wait sea transportation. Taylor was left with 4,800 men, practically all

volunteers, most or whom he concentrated in a camp south of Saltillo.

| Mexican-American War |

|

| General Winfield Scott |

Buena Vista, 22 - 23 February 1847. Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna, aka Santa Anna, President of Mexico, had meanwhile taken the field personally and assembled an army at Son

Luia Potosi. Learning of the weakness of the forces near Saltillo in February 1847, Santa Anna forwarded his estimated force

of 15,000 men. Taylor hastily redeployed his force at Buena Vista, where the terrain offered better possibilities for defense.

Santa Anna used French tactics at Buena Vista, attempting to overwhelm American positions with dense columns of men. Massed

tires of infantry and artillery proved effective against the attacking columns, and, after two days of the most severe fighting

of the war, Santa Anna withdrew his dispirited army to San Luis Potosi, having suffered from 1,500 to 2,000 men killed

and wounded. The Americans, too exhausted to pursue, had lost 264 killed, 450 wounded, and 26 missing.

Vera Cruz, 9 - 29 March 1847. Scott's army of 13,660

men rendezvoused at Lobos Island late in February 1847. On 2 March, it sailed for Vera Cruz, convoyed by a naval force

under Commodore Matthew C. Perry. Landing operations near Vera Cruz began on 9 March. This first major amphibious landing

by the U.S. Army was unopposed, because the Mexican commandante general, Juan Morales, had held his force of 4,300

men behind the city's walls. In order to save lives, Scott chose to take Vera Cruz by siege rather than by assault. The city

capitulated on 27 March 1847, after undergoing a demoralizing bombardment. The Americans lost 19 killed and 63 wounded. The

Mexican military suffered about 80 casualties.

Cerro Gordo, 17 April 1847. Scott began his advance

toward Mexico City on 8 April 1847. The first resistance encountered was near the hamlet of Cerro Gordo where Santa Anna had

strongly entrenched an army of about 12,000 men in mountain passes through which the road led to Jalapa. Scott quickly

won the battle with a flanking movement that cut off the enemy escape route, and the Mexicans surrendered in droves. Results:

From 1,000 to 1,200 casualties were suffered by the Mexicans. Scott eventually paroled an additional 3,000 that

had been captured. Santa Anna and the remnants of his army fled into the mountains. American losses were 64 killed and 353

wounded.

Scott quickly pushed on to Jalapa, but was forced to wait there for supplies

and reinforcements. After some weeks, he advanced cautiously to Pueblo. Wounds and sickness had placed 3,200 men in the

hospital. In addition, 3,700 volunteers (seven regiments), whose enlistments had expired, departed for home. The

ramifications: It left Scott with only 5,820 effectives at the end of May 1847. Scott remained at Puebla until the beginning

of August, awaiting reinforcement and the outcome of peace negotiations--which were being conducted by Nicholas P. Trist,

a State Department official who had accompanied the expedition.

The negotiations failed, so Scott boldly advanced toward Mexico City

on 7 August, thus abandoning his line of communications to the coast. By this time, reinforcements had brought his army to the

strength of nearly 10,000 men. Santa Anna had disposed his army in and around Mexico City, strongly fortifying the many natural

obstacles that lay in the way of the Americans.

Contreras, 18 - 20 August 1847. Scott first encountered

stiff resistance at Contreras where the Mexicans were finally put to flight after suffering an estimated 700 casualties and

the loss of 800 prisoners.

| Mexican-American War |

|

| General Zachary Taylor |

Churubusco, 20 August 1847. Santa Anna promptly made

another stand on Churubusco where he suffered a disastrous defeat in which his total losses for the day—killed, wounded,

and especially deserters—were (probably) as high as 10,000. Scott, however, estimated the Mexican losses at

4,297 killed and wounded, and 2,637 prisoners. Of 8,497 Americans engaged in the almost continuous battles of Contreras

and Churubusco, 131 were killed, 865 wounded and about 40 missing.

Scott proposed an armistice to discuss peace terms. Santa Anna quickly agreed;

but after two weeks of fruitless negotiations it became apparent that the Mexicans were using the armistice merely for a respite.

On 6 September, Scott canceled the negotiations and prepared to assault the capital. To do so, it was necessary to take the

citadel of Chapultepec, a massive stone fortress on top of a hill about a mile outside the city proper. Defending Mexico City

was from 18,000 to 20,000 troops, and the Mexicans were confident of victory, since it was known that "Scott had barely 8,000

men and was far from his base of supply."

Molino del Rey, 8 September 1847. On 8 September 1847,

the Americans launched an assault on Molino del Rey, the most important outwork of Chapultepec. It was taken after a bloody

fight, in which the Mexicans suffered an estimated 2,000 casualties and lost 700 as prisoners, while perhaps as many as 2,000

deserted. The small American force had sustained comparatively serious losses—124 killed and 582 wounded—but they

doggedly continued their attack on Chapultepec, which finally fell on 13 September 1847. American losses were 138

killed and 673 wounded during the siege of the fortress. Mexican losses in killed, wounded, and captured totaled 1,800.

The fall of the citadel brought Mexican resistance practically to an end. Authorities in Mexico City sent out a white flag

on 14 September 1847. Santa Anna abdicated the Presidency, and the last remnant of his army, about 1,500 volunteers, was completely

defeated a few days later while attempting to capture an American supply train.

On 2 February 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, ratified in the U.S. Senate on 10 March 1848, by the Mexican Congress in May, and on 1 August 1848, the

last American soldier departed for the United States. Subsequently, Mexico and the United States signed and ratified the Gadsden Purchase. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Gadsden Purchase were reflected in the United States' policy of Manifest Destiny.

Source: U.S. Army Center of Military History

|