|

Shenandoah Valley and Civil War

Introduction

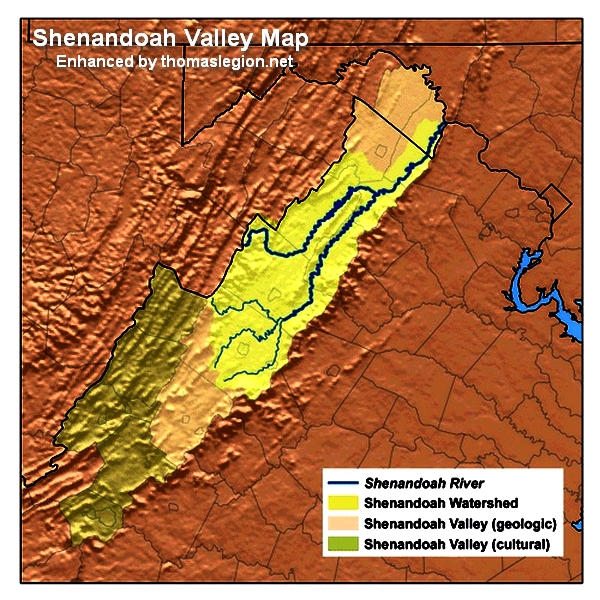

The Shenandoah Valley was known as the Breadbasket

of the Confederacy during the Civil War and seen as a back door for Confederate raids on Maryland, Washington and Pennsylvania.

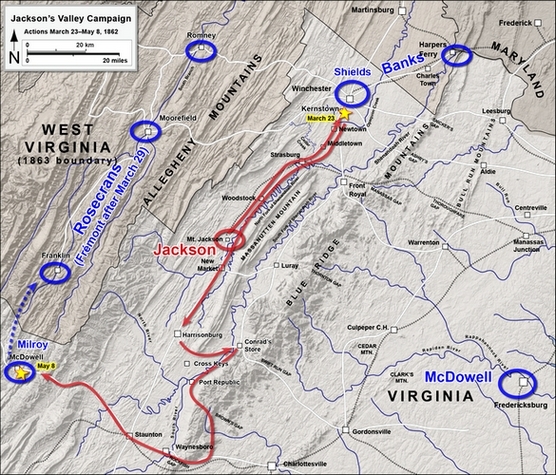

Because of its strategic importance it was the scene of three major campaigns. The first was the Valley Campaign of 1862,

in which Confederate General Stonewall Jackson successfully defended the valley against three numerically superior Union armies.

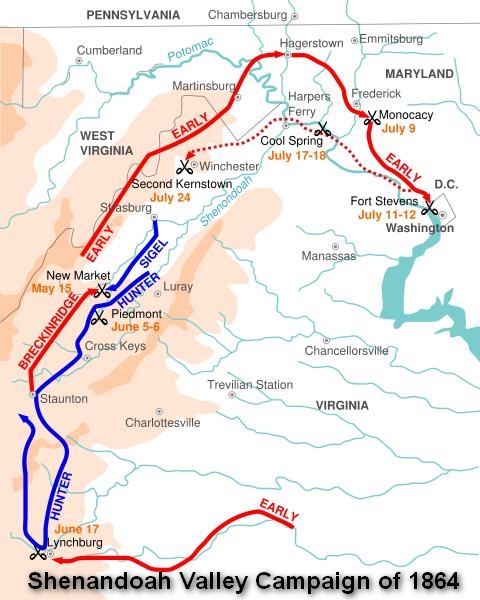

The final two were the Valley Campaigns of 1864. First, in the summer of 1864, Confederate General Jubal Early cleared the

valley of its Union occupiers and then proceeded to raid Maryland, Pennsylvania and D.C. Then during the Autumn, Union General

Philip Sheridan was sent to drive Early from the valley and once-and-for-all destroy its use to the Confederates by putting

it to the torch using scorched-earth tactics. The valley, especially in the lower northern section, was also the scene of

bitter partisan fighting as the region's inhabitants were deeply divided over loyalties, and Confederate partisans, such as John

Mosby and his Rangers, frequently operated in the area.

Significance

The Shenandoah Valley was a vital asset to the Confederacy from the beginning of the Civil

War. In a human sense, the Valley became invaluable in its ability to feed soldiers in the field. Militarily, the Valley gave

the South a unique geographical advantage in the Eastern Theater. Because a Confederate force moving down the Valley would

be marching northeast, the Valley could conveniently deposit an army not far west of the U.S.

capitol in Washington. On the other hand, United States forces in the Valley making a move southward would be taken away from the Confederate

capital in Richmond due to its southwest physicality. Another

advantage afforded Confederate forces in the Valley was the cover it provided. The mountains fronted an effective shield which

concealed the Southerners from prying Yankee eyes. Such secrecy was amply demonstrated in Jubal Early's raid on the defenses

of Washington in 1864. He nearly made it to the capital

before U.S. Grant even knew he was coming.

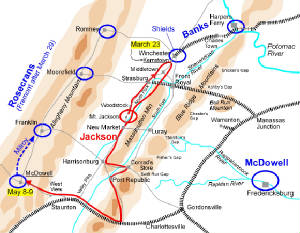

| 1862 Valley Campaign: Kernstown to McDowell |

|

| "Stonewall" Jackson in the Valley |

Valley Campaigns

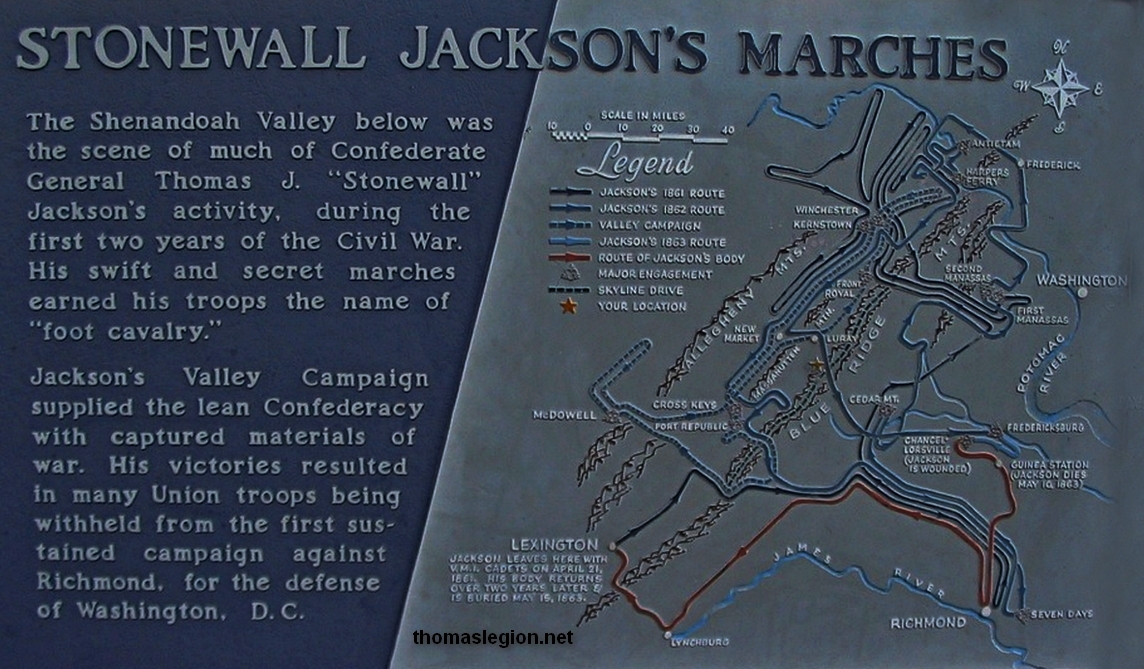

Early in the war, Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, formerly a professor

at Lexington's Virginia Military Institute, used his famous

"foot cavalry" and his mens' knowledge of the area to become master of the Valley. Because the Valley was in parts split by

intervening mountains as was the area just north of Port Republic

to Strasburg, a numerically inferior army could manage to "plug up" the gaps in the Valley and prevent offensive movement

by the United States.

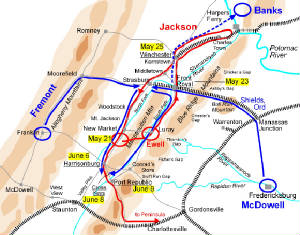

| 1862 Valley Campaign: Front Royal to Port Republic |

|

| "Stonewall" Jackson in the Valley |

Using this advantage to the fullest, as well

as taking advantage of extensive knowledge of the area, aided in part by Augusta County's Jedediah Hotchkiss "The

Mapmaker of the Confederacy", Stonewall managed to keep the United States

forces from penetrating too far down the valley without a swift rebuttal. Idolized throughout the Valley, this deeply religious

man came to be seen as its inhabitants' protector. The Shenandoah suffered a blow at the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 2,

1863. As dusk fell on the battlefield, Stonewall Jackson was mistakenly shot down by a regiment from North Carolina. He died seven days later.

In 1864 the Valley once again became the target of protracted invasion by the United States. In the spring, Major General Franz Sigel took

command of the Department of West Virginia. On April 29, Sigel headed up the Valley, with the plan to fight his way to Staunton. He was to meet there with Union forces under Brigadier General

George Crook. Crook's orders were to leave headquarters in West Virginia and assault the

Virginia & Tennessee Railroad at the New River

Bridge located between Christiansburg and Dublin.

Meanwhile, Brigadier General William Averell was to take command of Crook's cavalry and assault the Confederate salt mine

at Saltville. After their objectives were met, the two generals were to meet with Sigel in Staunton to destroy the Virginia Central Railroad. In response, Major General John Breckinridge,

formerly Vice President of the United States

under Buchanan, did his best in splitting up his undersized army to meet this triple threat. A part of Breckinridge's force

moved to protect Saltville. General Averell heard false reports of an overly-formidable force there and decided to try Wytheville

instead. The Confederates moved there quicker than he did and repulsed him in a trouncing on May 8. Their comrades guarding

Dublin from Crook's forces encountered them on the ninth and

were finally driven back after repeated charges, including several led by future U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes. The United States forces reached their objective the next day and burned the New River Bridge, despite an artillery barrage

from Colonel John McCausland. Interestingly, Crook then gathered up his forces and retreated west, saying later that he captured

a Confederate dispatch that said Lee had defeated Grant at the Battle

of the Wilderness. Crook feared being cut off by a portion of Lee's army. Crook and Averell made the long march back to West Virginia.

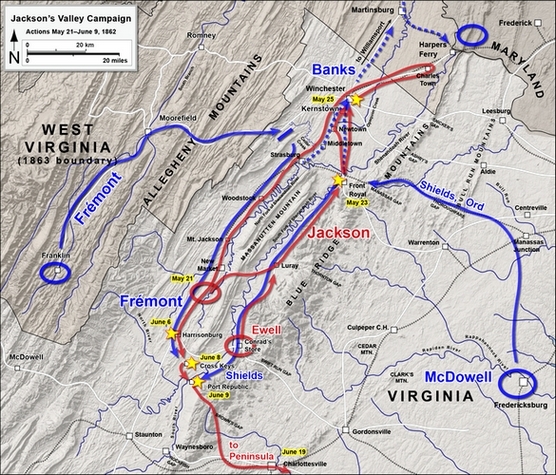

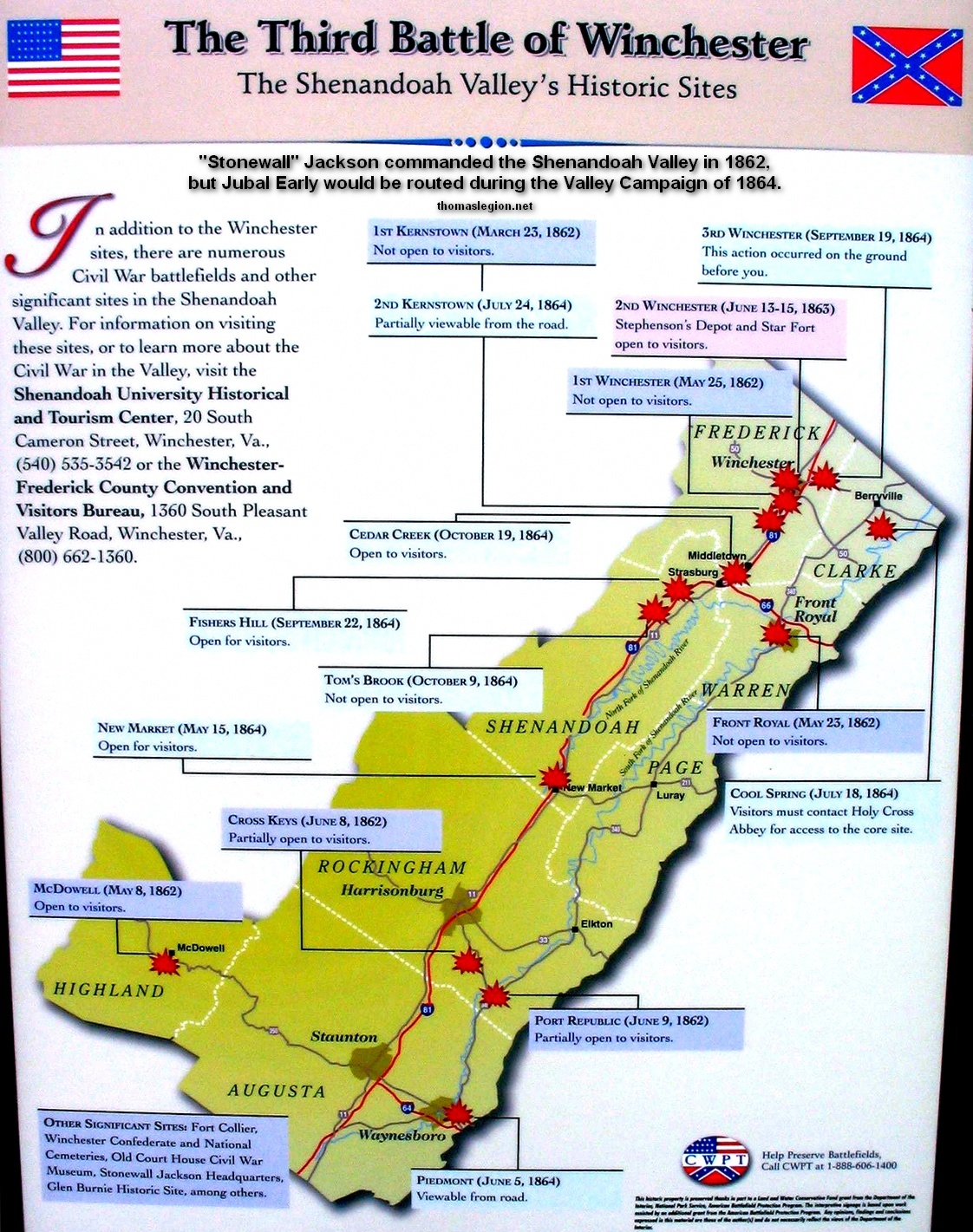

| Shenandoah Valley Civil War Battles and Campaigns |

|

| Shenandoah Valley Civil War Battles |

|

| Map 2 of 2 of Jackson's Valley Campaign, by Hal Jespersen |

|

| Map 1 of 2 of Jackson's Valley Campaign, by Hal Jespersen |

General Sigel was making a very slow march up the Valley, much to the benefit

of Breckinridge's scattered forces. He heard various rumors of Confederate forces all around him, and the "McClellan-esque"

general accordingly took his time, cautiously moving south. General Breckinridge organized at Staunton,

and on the 13th of May headed north with his forces, including the VMI Corps of Cadets. On May 15th, Breckinridge's forces

defeated Sigel at the Battle of New Market, which included the famed charge by the Corps. Saving the Shenandoah on the anniversary

of Stonewall's funeral, Breckinridge was being hailed as the "new Jackson", the Valley's new guardian.

General Lee wasted no time in recalling Breckinridge to help him fight Grant in the

east. This seemed sound practice because of the fact that in previous campaigns, a Confederate victory left the U.S. forces confused and inable to act for many months. The

difference this time was that U.S. Grant was in charge. If anything, Grant was known for his nose down, no-nonsense, continuous

attacks, and the Valley would soon find out that he had no intention of letting up. On May 26, the new U.S. commander, David Hunter, moved up the Valley, burning

houses as he went, despite Grant's order to only take things which were necessary for his troops. On the 30th, he reached

the New Market battlefield, only 15 days after the U.S.

defeat. The Confederate forces were in some confusion because of Breckinridge's departure. Leadership was finally given to

William E. "Grumble" Jones, and his forces rushed down the Valley to meet the U.S.

forces. They met at a little village named Piedmont on June 5th. Calling on the Home Guard

units, Jones force was still smaller than Hunter's, 5,000 to 8,500. The battle ended in Confederate defeat and death for General

Jones, who was personally leading a charge into the left flank of the 34th Massachusetts.

General Hunter moved for Staunton and captured it on the 6th. His forces wasted no time in burning Confederate stores,

dismantling the Virginia Central Railroad, and taking whatever they didn't torch. On the 8th, General Crook arrived, making

Hunter's combined force 18,000 men. Waiting for more supplies, and busy burning the Confederate holdings in Staunton, Hunter waited until the 10th to leave the town. His plan was to march south and

assault Lynchburg. The Valley was again in confusion, as Jones

was dead and much of his force incapacitated. Lee had no choice but to send in reinforcements from his own strained army at

Cold Harbor. He ordered Breckinridge back to Lynchburg,

and on June 13th, sent 8,000 men under Lieutenant General Jubal Early to the Valley.

| Shenandoah Valley Campaigns in May - August 1864 |

|

| General Early in the Shenandoah Valley Campaigns in May -- August 1864 |

Hunter was proceeding towards Lynchburg, and entered Lexington

along the way, burning VMI in the process. He reached Lynchburg

on the 17th, his huge army facing only about 2,000 soldiers under General Breckinridge. Night fell, and Hunter planned to

attack in the morning. The next day came, and Early's full force had not yet reached Lynchburg.

Hunter got word of Early's arrival and overestimated the strength of Early's battered corps. Subsequently, Hunter withdrew

to Staunton then headed west to the safety of the Kanawha

Valley in West Virginia.

The Confederacy was now in a rare position in 1864: the Valley was largely free of the United States forces. General Lee left General Early's next

move up to the latter's own discretion. A gleaming prize lay precariously unmanned to the northeast: Washington D.C. While the bulk of U.S. Grant's forces were

dealing with Lee's stubborn army, perhaps, just perhaps, Early could wreak havoc within the U.S. capital's walls. Therein lay the problem. The capital was surrounded by a

formidable ring of defenses, easily one of, if not the most heavily fortified city in the western hemisphere. Though these

defenses were there, there was only a relative handful of personnel manning its stations. Nearly all of Grant's Army of the

Potomac was busily wearing down Lee's army to the south. Early, having Lee's permission,

decided that he would move north, if not to conquer the city, then to force Grant to send a portion of his own force attacking

Lee to defend Washington. Either way, the offense would

aid Lee. A still more important factor in Early's decision had to do with the impending elections in the north. Though the

U.S. forces were everywhere on Southern soil, the Northern will to fight

was being doubted as Lincoln's reelection hopes were waning.

Perhaps a new president would make peace and bring the northern boys back home. For Lincoln

to be reelected, a major U.S. victory

was needed and it hadn't happened yet. Early's invasion could do much to breed further distaste for the war in the north.

Chasing Hunter down the Valley, Early arrived in Staunton on June 26 with his combined force of about 14,000 men. Along the way, Early's army

visited Lexington and paid their respects to General Jackson.

Early started north again on the 28th, reaching Winchester on the 2nd after a week of marching,

brilliantly hidden behind the Blue Ridge Mountains. He first encountered resistance at Harpers

Ferry on the 4th of July against U.S.

troops under the command of Franz Sigel, the commander at New Market. Sidestepping this stronghold, Early continued for Washington, defeating a confused United States

force on the 9th at the Monocacy river. Though he was the victor and had a straight shot to the capital, word was now spreading

of Early's approach. Grant detoured two of his corps to meet this new threat. On the 11th, Early came to Washington, meeting rather feebly manned defenses. He sent skirmishers to test the defenses,

but Grant's reinforcements had begun to arrive. On the 12th, the ramparts were fully manned and an assault by Early would

have been very costly indeed. Early retreated across the Potomac and repulsed the pursuing

forces at the Battle of Cool Spring on the 18th. The U.S.

forces kept coming, however, and Early kept retreating south. The U.S.

commander, Major General Horatio Wright was sure he had stifled the Confederates, and ordered Grant's two reinforcement corps

back to join Grant's main army.

| Shenandoah Valley Map |

|

| Shenandoah Valley was known as the Breadbasket of the Confederacy |

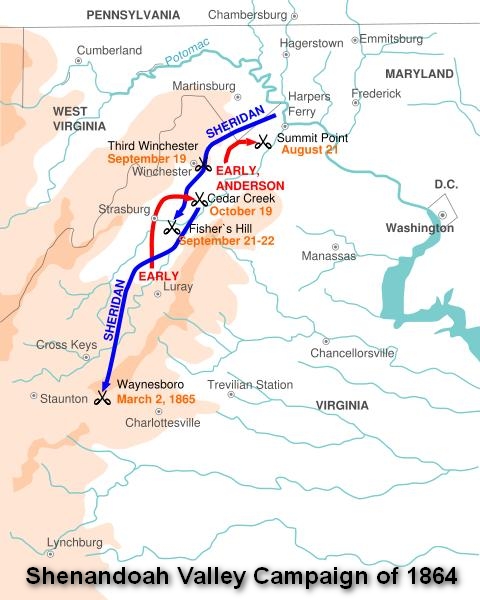

| August 1864 -- March 1865 Valley Operations Map |

|

| Jubal Early and his Army of the Valley are eliminated from the Valley in March 1865 |

Early now took the advantage of the overconfident Wright and soundly defeated the remaining

U.S. force July 24th under General Crook at the Battle of Second Kernstown. Seeking

revenge for General Hunter's pyromania in the Valley a month earlier, Early sent his cavalry under John McCausland to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. His orders

were to collect tribute or burn the city. When they failed to come up with the $100,000 in gold that McCausland demanded,

they watched their city burn to the ground on the 30th. An obviously lofty ransom, Early probably knew there was no way that

the citizens could come up with the money. Rather the general was seeking retribution for the travesties dealt Virginia at the hands of General Hunter.

General U.S. Grant had had enough. He returned his two corps relieved by General

Wright, and put General Philip Sheridan in command on August 7th. The Confederate threat was to be dealt with once and for

all. After various reinforcements, including the two corps, Sheridan's

army now numbered close to 50,000, a huge army. Grant wasn't going to settle for any more setbacks. Nevertheless, Early's

forces slowed the progress of Sheridan's southerly moving

army, rebuffing them on August 11th at Double Toll Gate. General Lee acted on this U.S.

setback and sent General Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry from Petersburg

to help Early's forces. These reinforcements were stopped in their tracks near Front Royal on the 16th by the U.S. Cavalry

commander George Custer of Little Bighorn fame. General Sheridan was unsure of the size of Early's army, and ordered to avoid

a defeat, made a defensive line south of Harpers Ferry and the Potomac.

Early hoped to take Sheridan's

entrenched men by surprise, moving to go around them and make another move for Maryland.

He left a small force behind to prevent Sheridan from moving

south. Unfortunately, Sheridan discovered Early's intentions

and attacked Early's remaining undersized force. This forced Early to forego his northern move and rescue his beleaguered

troops south of Harpers Ferry. The two armies now faced each other and engaged in a series

of assaults and counter-assaults along the Opequon Creek in late August and early September. A breakthrough was finally achieved

by the U.S. forces on the 19th at the

Battle of Opequon. Unfortunately for Early, a part of his force was ordered back to Petersburg

to help Lee. Sheridan took this opportunity to attack, and

after a flanking maneuver on Early's northern line, broke the Confederates.

| Shenandoah Valley in the Civil War |

|

| Shenandoah Valley would become the Valley of Death to thousands during the Civil War |

Jubal Early fell back to Fisher's Hill. Sheridan's army used the thick forest cover to surprise

the Confederates and thoroughly rout them on the 22nd. The C.S. forces fled all the way south to Rockfish Gap, east of Waynesboro. The Valley was basically open to Sheridan's whims. Sheridan

burned at will, this time behind the full consent of General Grant, who wanted to rid himself of the Shenandoah threat once

and for all. Lee reluctantly returned a part of his force to the Valley to reinforce Early at Rockfish Gap. The two forces

met in a notable battle at Cedar Creek on the morning of the 19th. The Confederates had marched all night in order to surprise

the sleeping Yankees. Surprise them they did, catching some in their tents, completely driving the U.S. forces from their camp. General Sheridan arrived from Winchester

after the initial U.S. retreat and effected

one of the most complete turnarounds of the war. He rallied his men and drove the Confederates from the field of battle. Early's army was now dreadfully outnumbered and further offensive actions were rebuffed

at every point. The winter came and Early's men entered their camps, saved from perhaps total defeat by Mother Nature. On

March 2nd, 1865, that defeat came at the Battle of Waynesboro. Early's small army was totally overwhelmed, and despite a valiant

stand, the Confederacy lost this last battle for the Shenandoah in the course of a few hours.

(See also related reading below.)

Sources: The Shenandoah in Flames, Valley Campaigns 1861-1865, The Shenandoah Valley in 1864; Maps by

Hal Jespersen in Adobe Illustrator CS5. Graphic source file is available at www.cwmaps.com.

Recommended Reading: Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign, by Peter Cozzens (Civil War America) (Hardcover). Description: In the spring of 1862,

Federal troops under the command of General George B. McClellan launched what was to be a coordinated, two-pronged attack

on Richmond in the hope of taking the Confederate capital

and bringing a quick end to the Civil War. The Confederate high command tasked Stonewall Jackson with diverting critical Union

resources from this drive, a mission Jackson fulfilled by repeatedly defeating much larger enemy forces. His victories elevated

him to near iconic status in both the North and the South and signaled a long war ahead. One of the most intriguing and storied

episodes of the Civil War, the Valley Campaign has heretofore only been related from the Confederate point of view. Continued

below…

With Shenandoah 1862, Peter Cozzens

dramatically and conclusively corrects this shortcoming, giving equal attention to both Union and Confederate perspectives. Based

on a multitude of primary sources, Cozzens's groundbreaking work offers new interpretations of the campaign and the reasons

for Jackson's success. Cozzens also demonstrates instances

in which the mythology that has come to shroud the campaign has masked errors on Jackson's

part. In addition, Shenandoah 1862 provides the first detailed appraisal of Union leadership in the Valley Campaign, with

some surprising conclusions. Moving seamlessly between tactical details and analysis of strategic significance, Cozzens presents

the first balanced, comprehensive account of a campaign that has long been romanticized but never fully understood. Includes

13 illustrations and 13 maps. About the Author: Peter Cozzens is an independent scholar and Foreign Service officer with the

U.S. Department of State. He is author or editor of nine highly acclaimed Civil War books, including The Darkest Days of the

War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth (from the University

of North Carolina Press).

Recommended Reading:

The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864 (McFarland & Company). Description: A significant part of the Civil War was fought in the Shenandoah

Valley of Virginia, especially in 1864. Books and articles have been written about the fighting that took place there, but

they generally cover only a small period of time and focus on a particular battle or campaign. Continued below.

This work covers

the entire year of 1864 so that readers can clearly see how one event led to another in the Shenandoah Valley and turned once-peaceful

garden spots into gory battlefields. It tells the stories of the great leaders, ordinary men, innocent civilians, and armies

large and small taking part in battles at New Market, Chambersburg, Winchester, Fisher’s

Hill and Cedar Creek, but it primarily tells the stories of the soldiers, Union and Confederate,

who were willing to risk their lives for their beliefs. The author has made extensive use of memoirs, letters and reports

written by the soldiers of both sides who fought in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864.

Recommended Reading: Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign,

Spring 1862. Description: The Valley Campaign conducted by Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson has

long fascinated those interested in the American Civil War as well as general students of military history, all of whom still

question exactly what Jackson did in the Shenandoah in 1862

and how he did it. Since Robert G. Tanner answered many questions in the first edition of Stonewall in the Valley in 1976,

he has continued to research the campaign. This edition offers new insights on the most significant moments of Stonewall's

Shenandoah triumph. Continued below...

About the Author: Robert G. Tanner

is a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute. Tanner is a native of Southern California, he now lives and practices law

in Atlanta,

Georgia. He has studied and lectured on the Shenandoah Valley

Campaign for more than twenty-five years.

Recommended

Reading:

Three Days in the Shenandoah: Stonewall Jackson at Front Royal and Winchester (Campaigns and Commanders) (Hardcover). Description: The battles

of Front Royal and Winchester are the stuff of Civil War legend.

Stonewall Jackson swept away an isolated Union division under the command of Nathaniel Banks and made his presence in the

northern Shenandoah Valley so frightful a prospect that it triggered an overreaction from

President Lincoln, yielding huge benefits for the Confederacy. Continued below…

Gary Ecelbarger has undertaken

a comprehensive reassessment of those battles to show their influence on both war strategy and the continuation of the conflict.

Three Days in the Shenandoah answers questions that have perplexed historians for generations. About the Author: Gary Ecelbarger,

an independent scholar, is the author of Black Jack Logan: An Extraordinary Life in Peace and War and "We Are in for It!":

The First Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862.

Recommended Reading: The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862, by Gary W. Gallagher.

Description: In eight new essays, contributors to this volume explore the Shenandoah Valley campaign, best known for its role

in establishing Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's reputation as a Confederate hero. In

early 1862, Union troops under George B. McClellan had arrived within range of Richmond

and threatened to take the Confederate capital. Robert E. Lee ordered Jackson to march north

through the Shenandoah Valley, hoping to tie down Federal forces that might otherwise reinforce

McClellan's troops. The strategy worked, and for two months the Confederates evaded and harassed their Union pursuers. Jackson's speed and audacity boosted plummeting Southern morale, and

he emerged from the Valley as the Confederacy's greatest military idol. Continued

below…

Contributors address questions

of military leadership, strategy and tactics, the campaign's political and social impact, and the ways in which participants'

memories of events differed from what is revealed in the historical sources. In the process, they offer valuable insights

into one of the Confederacy's most famous generals, those who fought with him and against him, the campaign's larger importance

in the context of the war, and the complex relationship between history and memory. Contributors include Jonathan M. Berkey,

Keith S. Bohannon, Peter S. Carmichael, Gary W. Gallagher, A. Cash Koeniger, R. E. L. Krick, Robert K. Krick, and William

J. Miller. About the Author: Gary W. Gallagher is John L. Nau III Professor of History at the University

of Virginia. He is author, most recently, of Lee and His Army in Confederate

History.

Recommended

Reading: Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Description: Jubal A. Early’s disastrous battles in the Shenandoah Valley

ultimately resulted in his ignominious dismissal. But Early’s lesser-known summer campaign of 1864, between his raid

on Washington and Phil Sheridan’s renowned fall campaign, had a significant impact on the political and military landscape

of the time. By focusing on military tactics and battle history in uncovering the facts and events of these little-understood

battles, Scott C. Patchan offers a new perspective on Early’s contributions to the Confederate war effort—and

to Union battle plans and politicking. Patchan details the previously unexplored battles at Rutherford’s Farm and Kernstown

(a pinnacle of Confederate operations in the Shenandoah Valley) and examines the campaign’s

influence on President Lincoln’s reelection efforts. Continued below…

He also provides

insights into the personalities, careers, and roles in Shenandoah of Confederate General John C. Breckinridge, Union general

George Crook, and Union colonel James A. Mulligan, with his “fighting Irish” brigade from Chicago.

Finally, Patchan reconsiders the ever-colorful and controversial Early himself, whose importance in the Confederate military

pantheon this book at last makes clear. About the Author: Scott C. Patchan, a Civil War battlefield guide and historian, is

the author of Forgotten Fury: The Battle of Piedmont, Virginia, and a consultant and contributing writer for Shenandoah, 1862.

Review

"The author's

descriptions of the battles are very detailed, full or regimental level actions, and individual incidents. He bases the accounts

on commendable research in manuscript collections, newspapers, published memoirs and regimental histories, and secondary works.

The words of the participants, quoted often by the author, give the narrative an immediacy. . . . A very creditable account

of a neglected period."-Jeffry D. Wert, Civil War News (Jeffry D. Wert Civil War News 20070914)

"[Shenandoah

Summer] contains excellent diagrams and maps of every battle and is recommended reading for those who have a passion for books

on the Civil War."-Waterline (Waterline 20070831)

"The narrative

is interesting and readable, with chapters of a digestible length covering many of the battles of the campaign."-Curled Up

With a Good Book (Curled Up With a Good Book 20060815)

"Shenandoah

Summer provides readers with detailed combat action, colorful character portrayals, and sound strategic analysis. Patchan''s

book succeeds in reminding readers that there is still plenty to write about when it comes to the American Civil War."-John

Deppen, Blue & Grey Magazine (John Deppen Blue & Grey Magazine 20060508)

"Scott C. Patchan

has solidified his position as the leading authority of the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign with his outstanding campaign

study, Shenandoah Summer. Mr. Patchan not only unearths this vital portion of the campaign, he has brought it back to life

with a crisp and suspenseful narrative. His impeccable scholarship, confident analyses, spellbinding battle scenes, and wonderful

character portraits will captivate even the most demanding readers. Shenandoah Summer is a must read for the Civil War aficionado

as well as for students and scholars of American military history."-Gary Ecelbarger, author of "We Are in for It!": The First

Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862 (Gary Ecelbarger 20060903)

"Scott Patchan

has given us a definitive account of the 1864 Valley Campaign. In clear prose and vivid detail, he weaves a spellbinding narrative

that bristles with detail but never loses sight of the big picture. This is a campaign narrative of the first order."-Gordon

C. Rhea, author of The Battle of the Wilderness: May 5-6, 1864 (Gordon C. Rhea )

"[Scott Patchan]

is a `boots-on-the-ground' historian, who works not just in archives but also in the sun and the rain and tall grass. Patchan's

mastery of the topography and the battlefields of the Valley is what sets him apart and, together with his deep research,

gives his analysis of the campaign an unimpeachable authority."-William J. Miller, author of Mapping for Stonewall and Great

Maps of the Civil War (William J. Miller)

Try the Search Engine for Related Studies: Shenandoah Valley Civil War History, General Phil

Sheridan Valley Campaign List of Battles Battlefields, General Jubal Anderson Valley Campaigns, 3rd or Third Winchester, Opequon

Civil War Virginia Map

|