|

Civil War in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864

| Shenandoah Valley in the Civil War |

|

| Shenandoah Valley Campaigns of 1864 |

Introduction

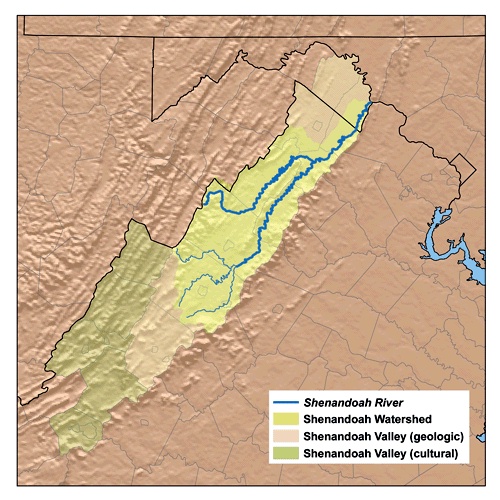

Throughout the Civil War, Confederate armies used the Shenandoah Valley

as a natural corridor to invade or threaten invasion of the North. Because of its southwest-northeast orientation, Confederate

armies marching down the Valley approached Washington and Baltimore, while Union armies marching up the Valley moved farther

away from Richmond. The Blue Ridge served as a natural screen for the movement of troops. By defending the gaps with cavalry,

Confederate forces could move swiftly north behind the protective wall of the Blue Ridge into Maryland and Pennsylvania, which

Gen. Robert E. Lee accomplished during the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863, as well as Jubal Early in 1864. The Blue Ridge

offered similar protection to Lee's army during its retreats from Antietam and Gettysburg.

When the need arose, Confederate defenders could hold the gaps in reverse

against a Union army operating in the Valley. By withdrawing to the Blue Ridge near Brown's Gap to protect Charlottesville

and eastern Virginia, the Confederates could threaten the flank and rear of any Union forces intent on penetrating the Upper

Valley. The western gaps in the Allegheny chain were defended by Confederates against sporadic Union feints and incursions

from West Virginia.

On the whole, Confederate armies succeeded in preventing deep Union

penetration of the Upper Valley until late in the war, and Valley geography cooperated with the defense. Where the Massanutten

Mountain rises abruptly between Front Royal and Strasburg, the width of the Valley is greatly decreased. With strong infantry

at Fisher's Hill in the main valley south of Strasburg and cavalry at Overall (antebellum Milford) in the Luray Valley, a

Confederate general could effectively hold the Upper Valley against a numerically superior enemy. Fisher's Hill astride the

Valley Turnpike was an important strategic "choke point" throughout the war.

If Confederate generals chose to withdraw up the Valley Turnpike from

Fisher's Hill, any pursuing Union general was forced to split his forces at the Massanutten in order to cover an advance up

both the main and the Luray valleys. Once divided, he could not again reunite his forces for more than fifty miles because

of the intervening mountain. Only a single rough road crossed the Massanutten--running from New Market to Luray through the

New Market Gap.

Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson used Massanutten Mountain to screen his

offensive movements in the 1862 Valley Campaign. Crossing from New Market to the Luray Valley in May, he advanced on Front

Royal and then on Winchester, forcing the Union army, then at Strasburg, into abrupt withdrawal. Later in the campaign, he

prevented two Union columns advancing against him up the main and Luray valleys from reuniting and defeated each separately

in the climax of his campaign at the battles of Cross Keys and Port Republic.

The Shenandoah Valley was referred to as the "Granary of Virginia."

It was the richest agricultural region in Virginia, and its abundance supplied the Confederate cause. Because a large number

of the inhabitants of Frederick, Shenandoah, Rockingham, and Augusta counties were pacifist Quakers or Dunkers who refused

to fight in the war, the Valley continued to produce horses, grains, and livestock even after other portions of Virginia were

made barren by the flight of slaves or the enlistment and conscription of the farmers. As the war continued, the City of Richmond

and the Army of Northern Virginia, pinned down in the trenches at Richmond and Petersburg, came to depend more heavily on

produce shipped from the Valley on the Virginia Central Railroad. Capturing the supply depot of Staunton and severing this

railroad became a major objective of the Union armies in 1864.

As the war progressed, Lynchburg also became an important objective

of Union campaigns in the Valley. In 1864, several expeditions began up the Valley from Winchester, and north from Bulls

Gap, Tennessee, with the objective of capturing Lynchburg, but the city remained in Confederate hands until the end of the

war.

By 1865, battlefield attrition would prove costly for the Confederacy while Union manpower and resources

would continue to reinforce its armies in the field. Lt. Gen. Jubal Early resigned after his defeat at the Battle of Waynesboro

on March 2, and Lee would surrender to Grant the following month on April 9 at Appomattox Court House.

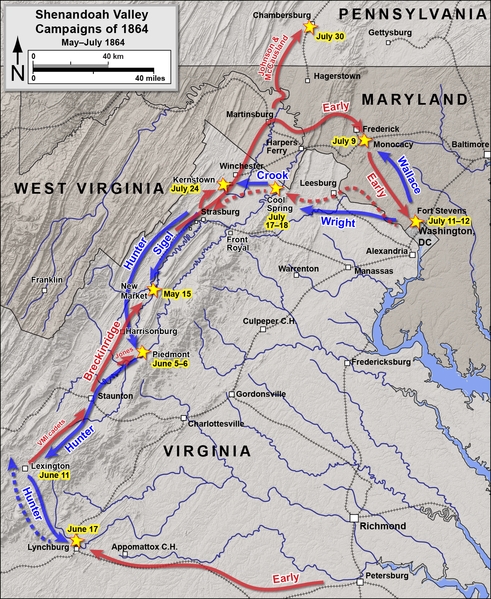

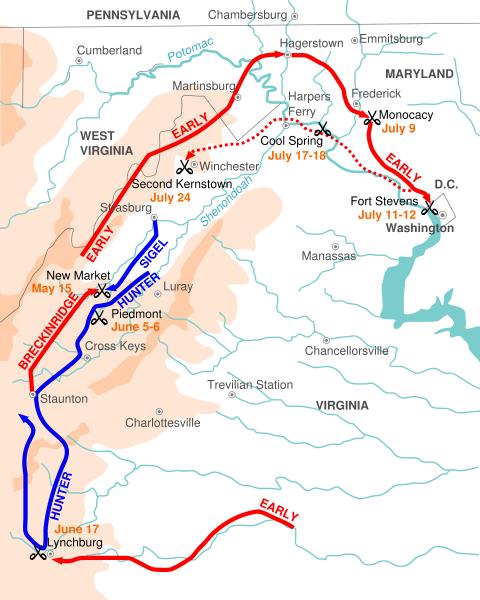

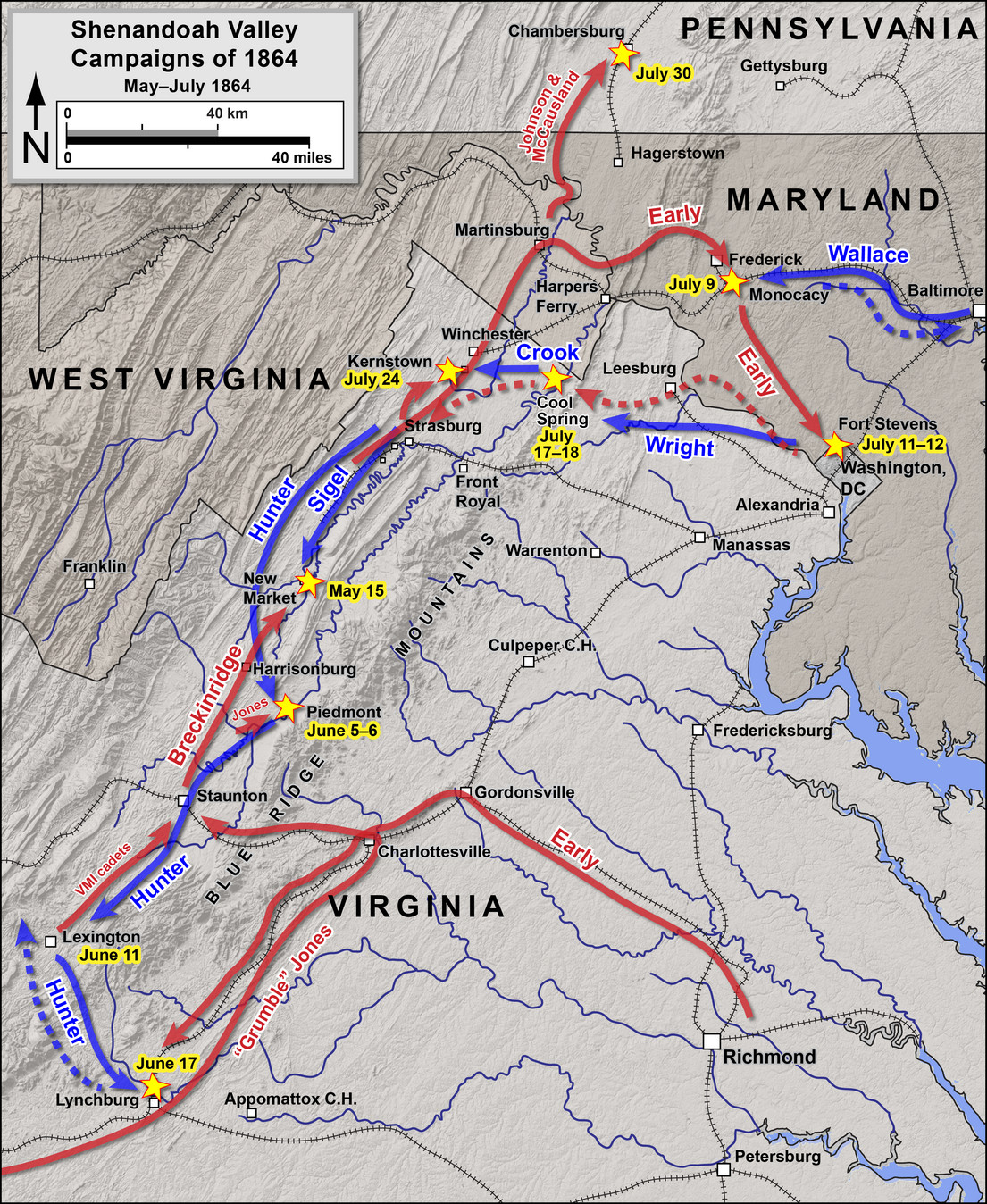

Lynchburg Campaign (May-June 1864)

In March 1864, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant assumed overall command of

the Union armies, east and west. In May, he ordered Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel to cooperate with the Army of the Potomac's spring

offensive by advancing up the Valley to disrupt Confederate communications at Staunton and

Charlottesville. On May 15, while Grant and Lee were locked

in desperate combat at Spotsylvania Court House, Sigel made contact with a Confederate force under former vice president of the United States John C. Breckinridge at New Market. Sigel was defeated and retreated rapidly beyond Strasburg, crossing Cedar Creek by dusk on May 16. Grant then

replaced Sigel with Maj. Gen. David "Black Dave'' Hunter, who was given the task of cutting the Virginia Central Railroad.

Lynchburg Campaign [May-June 1864] consisted of the following battles:

New Market – Piedmont – Lynchburg.

In the meantime, Breckinridge's division had been called east to reinforce

the Army of Northern Virginia at Hanover Junction, and Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble'' Jones assumed command of the remaining

Confederate forces in the Valley. On June 5, Hunter crushed the smaller Confederate army at Piedmont, killing Jones and taking nearly 1,000 prisoners. The disorganized Confederates could do nothing to delay Hunter's advance

to Staunton, where he was joined by reinforcements marching from West Virginia.

From Staunton,

Hunter continued south, sporadically destroying mills, barns, and public buildings, and condoning widespread looting by his

troops. On June 11, Hunter swept aside a small cavalry force and occupied Lexington,

where he burned the Virginia Military Institute and the home of former Virginia Governor John Letcher. Hunter's successes

forced Lee to return Breckinridge and to send the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia under Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early

to the defense of Lynchburg. Sending Early to the Valley was a desperate decision that restricted Lee's ability to undertake offensive operations against

Grant on the Richmond-Petersburg front (see Siege of Petersburg).

On the afternoon of June 17, Hunter's army reached the outskirts of Lynchburg, even as Early's vanguard began to arrive by rail from Charlottesville.

After a brief, but fierce engagement, Hunter retreated into West Virginia.

Early pursued for two days, but then returned to the Valley and started his troops north to the Potomac

River.

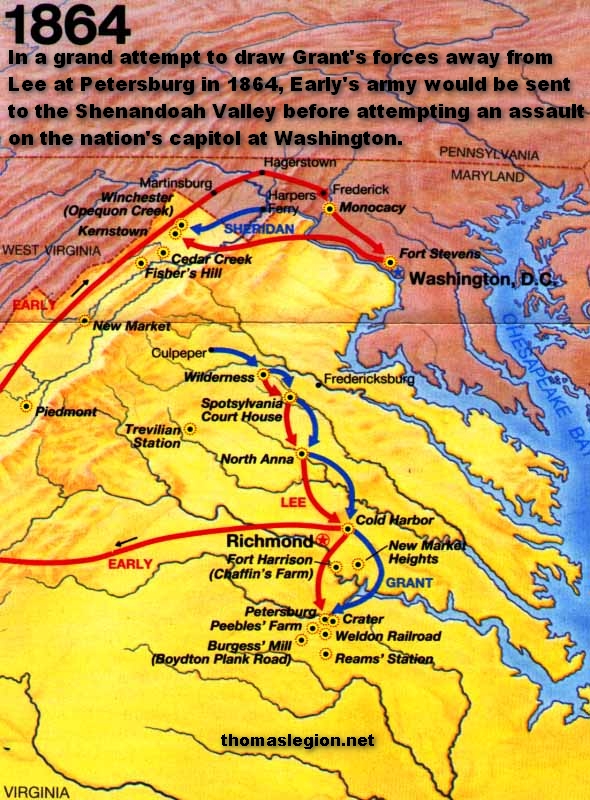

| 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign Map |

|

| Civil War Shenandoah Valley Campaign in May -- July 1864 |

| Shenandoah Valley Campaigns in May -- August 1864 |

|

| Shenandoah Valley Campaigns in May -- August 1864 |

Early's Maryland Campaign (June-August 1864)

Hunter's retreat left the Shenandoah Valley virtually undefended,

and Early moved swiftly north, reaching Winchester by July 2. General Sigel, commanding a reserve division, withdrew to Maryland Heights at Harpers Ferry, offering little resistance. On July 4,

Early confronted Sigel but then determined to turn the position by crossing the Potomac and moving over South

Mountain to Frederick, Maryland. On July 9, Early defeated a hastily organized Union force under Maj. Gen. Lew

Wallace at the Monocacy River. Wallace retreated toward Baltimore,

leaving open the road to Washington, but his defeat had

bought valuable time. (Maryland Civil War History.)

On the afternoon of July 11, Early's command, numbering no more than

12,000 infantry, demonstrated before the Washington fortifications,

which were weakly manned by garrison troops. Veteran reinforcements (VI and XIX Corps), diverted from Grant's army to meet

the threat on the capital, began arriving at mid- day, and by July 12, fully manned the Washington

entrenchments. After a brief demonstration at Fort Stevens, Early called off an attack on the capital. The Confederate army withdrew that night, recrossed the Potomac

River at White's Ford and reentered the Valley by Snickers Gap. Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, commanding the pursuing

Union army, attempted to bring Early to bay.

On July 18, a Union division crossed the Shenandoah River west of Snickers Gap but was

thrown back at the battle of Cool Spring. Union cavalry were turned back at Berry's Ferry, nine

miles farther south, the next day. On July 20, Union Brig. Gen. William Averell's mounted command, backed by infantry, moved

south from Martinsburg on the Valley Turnpike and attacked the infantry division of Maj. Gen. Stephen D. Ramseur at Rutherford's Farm near Winchester and routed it. In response to this setback and converging threats, Early withdrew to Fisher's Hill south

of Strasburg.

Early's withdrawal convinced Wright that he had accomplished his task

of driving off the Confederate invaders. He therefore ordered the VI and XIX Corps to return to Alexandria,

where they would board transports to join the Army of the Potomac. Wright left Crook with

three small infantry divisions and a cavalry division at Winchester

to cover the Valley.

Under a standing directive to prevent Union reinforcements from reaching Grant,

Early was quick to take advantage of Wright's departure. He attacked and routed Crook's command at Second Kernstown on July 24, and pressed the retreating Union forces closely. When

Crook retreated toward Harpers Ferry, Early sent his cavalry to Chambersburg,

Pennsylvania, to exact tribute or burn the city. The citizens refused to comply,

and McCausland's cavalry burned the center of the town in retaliation for Hunter's excesses in the Valley.

| 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign Map |

|

| Civil War in Shenandoah Valley during 1864 |

| Civil War Shenandoah Valley Campaign Map |

|

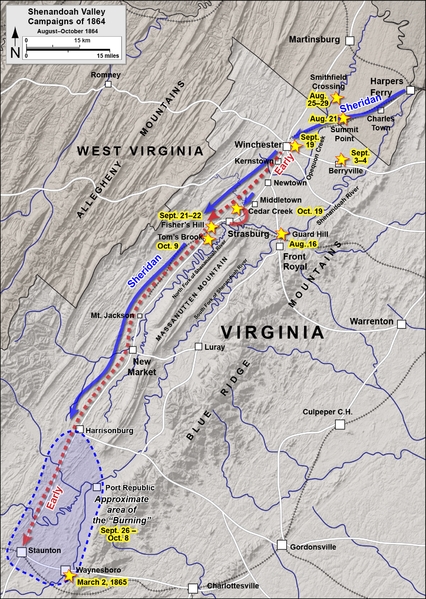

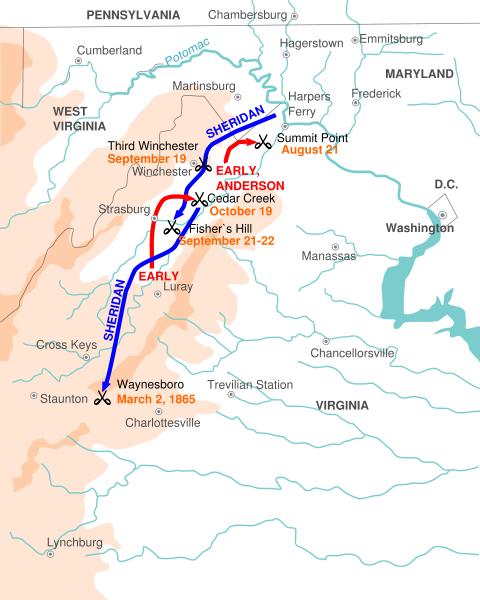

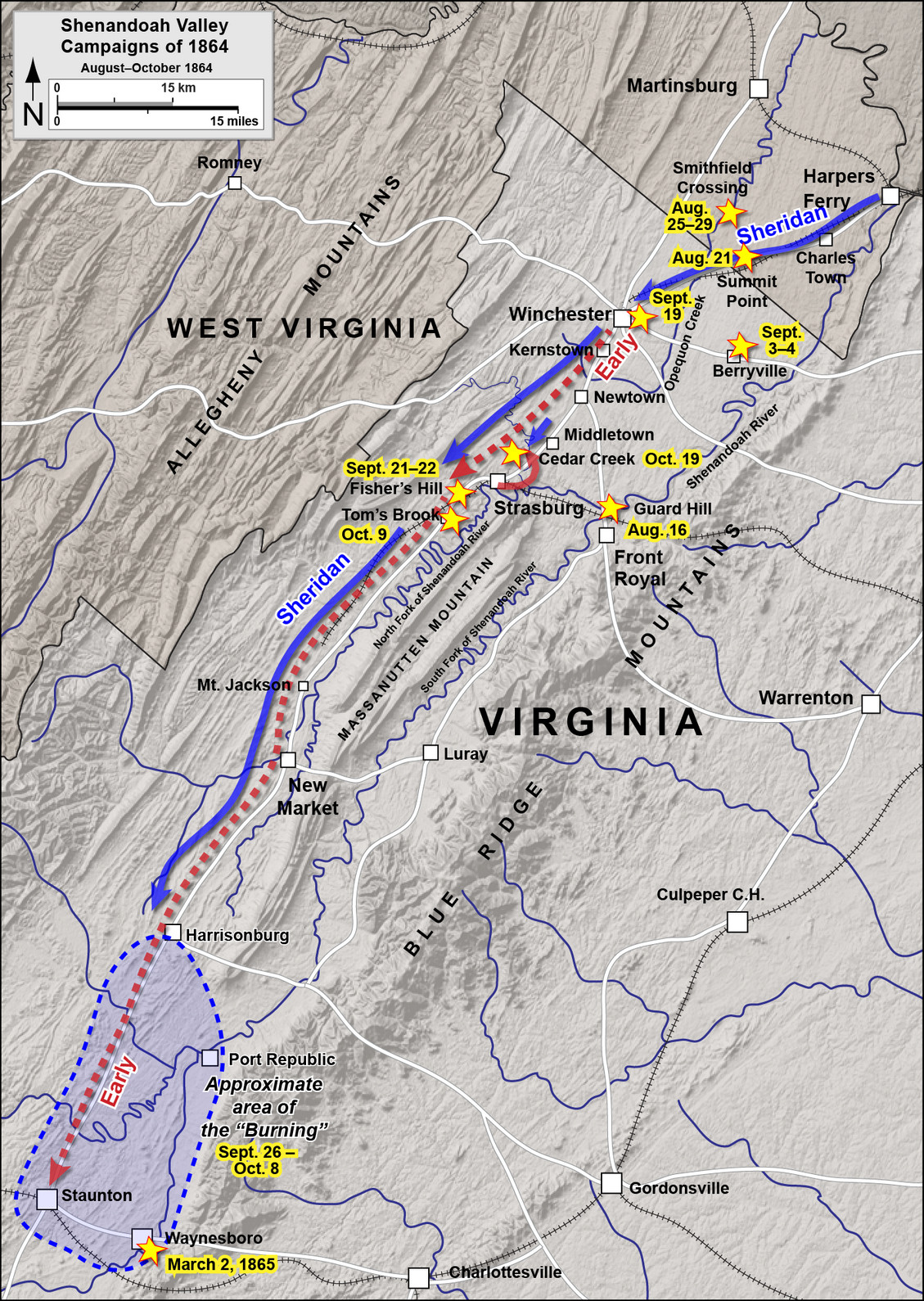

| 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaigns in August -- October 1864 |

| Civil War in the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia |

|

| Shenandoah Valley Campaigns in August 1864 -- March 1865 |

Sheridan's Valley Campaign (August 1864-March 1865)

Early's threat to Washington, Crook's defeat at Second Kernstown, and

the burning of Chambersburg, forced Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant move decisively to end the Confederate threat in the lower Shenandoah

Valley. Grant returned the VI and XIX Corps to the Valley, reinforced by two divisions of cavalry, and consolidated the various

military districts of the region under Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, who assumed command of the Middle Military District at

Harpers Ferry

on August 7.

Sheridan's

Valley Campaign [August-October 1864] witnessed the following battles: Guard Hill – Summit Point – Smithfield Crossing – Berryville – 3rd Winchester – Fisher's Hill – Tom's Brook – Cedar Creek.

Early deployed his forces to defend the approaches to Winchester,

while Sheridan moved his army, now 50,000 strong, south via

Berryville with the goal of cutting the Valley Turnpike. On August 11, Confederate cavalry and infantry turned back Union

cavalry at Double Toll Gate in sporadic, day-long fighting, preventing this maneuver.

Lee was quick to reinforce success and sent Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw's

infantry division of the First Corps, Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry division, and an artillery battalion, under overall command of

Lt. Gen. Richard Anderson, to join Early. On August 16, Union cavalry encountered this force advancing through Front Royal,

and in a sharp engagement at Guard Hill, Brig. Gen. George A. Custer's brigade captured more than 300 Confederates.

Sheridan had been ordered to move cautiously

and avoid a defeat, particularly if Early were reinforced from the Petersburg

line. Uncertain of Early's and Anderson's combined strength, Sheridan

withdrew to a defensive line near Charles Town to cover the Potomac River crossings and Harpers Ferry.

Early's forces routed the Union rear guard at Abrams Creek at Winchester on August 17 and pressed

north on the Valley Turnpike to Bunker Hill. Judging Sheridan's

performance thus far, General Early considered him a "timid'' commander.

On August 21, Early and Anderson launched

a converging attack against Sheridan. As Early struck the

main body of Union infantry at Cameron's Depot, Anderson moved north from Berryville against

Sheridan's cavalry at Summit Point. Results of the fighting were inconclusive, but Sheridan

continued to withdraw. The next day, Early advanced boldly on Charles Town, panicking a portion of the retreating Union army,

but by late afternoon, Sheridan had retreated into formidable entrenchments at Halltown, south

of Harpers Ferry, where he was beyond attack.

Early then attempted another incursion into Maryland, hoping by this maneuver to maintain the initiative. Leaving Anderson

with Kershaw's division entrenched in front of Sheridan at

Halltown, he directed the rest of the army north toward Shepherdstown. On August 25, two divisions of Sheridan's

cavalry intercepted Early's advance, but the Confederate infantry drove them back to the Potomac River

in a series of actions along Kearneysville- Shepherdstown Road.

Early's intentions were revealed, however, and on August 26, Sheridan's

infantry attacked and overran a portion of the Confederate entrenchments at Halltown, forcing Anderson and Kershaw to withdraw

to Stephenson's Depot. Early abandoned his raid and returned south, establishing a defensive line on the west bank of Opequon

Creek from Bunker Hill to Stephenson's Depot.

| Civil War in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign Map |

|

| Shenandoah Valley Campaign Map |

|

| Shenandoah Valley |

On August 29, Union cavalry forded the Opequon at Smithfield Crossing (Middleway) but were swiftly driven back across the creek and beyond the hamlet by Confederate infantry. Union infantry of

the VI Corps then advanced and regained the line of the Opequon. This was one more in a series of thrusts and parries that

characterized this phase of the campaign, known to the soldiers as the ``mimic war.''

On September 2-3, Averell's cavalry division rode south from Martinsburg

and struck the Confederate left flank at Bunker Hill, defeating the Confederate cavalry but being driven back by infantry. Meanwhile, Sheridan concentrated his infantry near Berryville. On the afternoon of September 3, Anderson's command encountered

and attacked elements of Crook's corps (Army of West Virginia) at Berryville but was repulsed. Early brought his entire army

up on the 4th, but found Sheridan's position at Berryville

too strongly entrenched to attack. Early again withdrew to the Opequon line.

On September 15, Anderson with Kershaw's

division and an artillery battalion left the Winchester area to return to Lee's army at Petersburg and by the 18th had reached the Virginia Piedmont. Early

spread out his remaining divisions from Winchester to Martinsburg,

where he once more cut the B&O Railroad. When Sheridan learned of Anderson's departure and the raid on Martinsburg, he determined to attack at once while the

Confederate army was scattered.

On September 19, Sheridan

advanced his army on the Berryville Turnpike, precipitating the battle of Opequon.

By forced marches, Early concentrated his army in time to intercept Sheridan's

main blow. The battle raged all day on the hills east and north of Winchester. Early's veterans decimated two divisions of the XIX Corps and a VI Corps division in fighting in the Middle Field and near

the Dinkle Barn. Confederate division commander Maj. Gen. Robert E. Rodes and Union division commander Brig. Gen. David A.

Russell were killed within a few hundred yards of one another in the heat of the fighting. Late in the afternoon a flanking

movement by Crook's corps and the Union cavalry finally broke Early's overextended line north of town. Opequon was a do-or-die

effort on the part of both armies, resulting in nearly 9,000 casualties.

Sheridan's

victory was decisive but incomplete; Early retreated twenty miles south to his entrenchments at Fisher’s Hill and Sheridan

followed. Preliminary skirmishing on the 21st showed that a frontal assault would be costly, so Sheridan resorted to a flanking movement on September 22. Hidden from the Confederate signal

station on Massanutten Mountain

by the dense forest, Crook's two divisions marched along the shoulder of Little North Mountain to get behind the Confederate

lines. In late afternoon, Crook's soldiers fell on Early's left flank and rear ``like an avalanche,'' throwing the Confederate

army into panicked retreat. At Milford (Overall) in the Luray Valley on the same day Confederate cavalry

prevented two divisions of Union cavalry from reaching Luray and passing New Market Gap to intercept Early's defeated army

as it withdrew up the Valley.

Early retreated to Rockfish Gap near Waynesboro, opening the Valley to Union depredations and what became known as ``The Burning''

or ``Red October.'' Sheridan thought he had destroyed Early's

army, but Kershaw's division and another brigade of cavalry were returned to the Valley, nearly making up the losses suffered

at Opequon and Fisher's Hill. After convincing Grant that he could proceed no farther than Staunton, Sheridan withdrew down

the Valley systematically burning mills, barns, and public buildings, destroying or carrying away the forage, grain, and livestock.

During this portion of the campaign, Confederate partisan groups under John S. Mosby and Harry Gilmor increased their activities

against Union supply lines in the Lower Valley.

Early followed Sheridan's

withdrawal, sending his cavalry under Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Rosser to harass the Union rear guard. Angered by Rosser's constant

skirmishing, Sheridan ordered his commander of cavalry, Maj.

Gen. Alfred T. Torbert, to ``whip the enemy or get whipped yourself.'' On October 9, Torbert unleashed the divisions of his

young generals, Wesley Merritt and George Custer, on the Confederate cavalry, routing it at Tom’s Brook. In the melee

that followed, victorious Union troopers chased the Confederates twenty miles up the pike and eight miles up the Back Road,

in what came to be known as the ``Woodstock Races.'' The morale and efficiency of the Confederate cavalry were seriously impaired

for the rest of the war.

On October 13, Early reoccupied Fisher's Hill and pushed through Strasburg

to Hupp's Hill where he engaged a portion of Sheridan's army.

When Sheridan realized the proximity of Early's forces, he

recalled the VI Corps, which had again been dispatched to join Grant. On October 19, at dawn, after an unparalleled night

march, Confederate infantry directed by Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon surprised and overwhelmed the soldiers of Crook's corps in

their camps at Cedar Creek. The XIX Corps suffered a like fate as the rest of Early's army joined the attack. Only the VI Corps maintained its order

as it withdrew beyond Middletown, providing a screen behind

which the other corps could regroup.

Sheridan, who was absent when the attack began, arrived on the field

from Winchester and immediately began to organize a counterattack,

saying ``if I had been with you this morning, boys, this would not have happened.'' In late afternoon, the Union army launched

a coordinated counterattack that drove the Confederates back across Cedar Creek. Sheridan's

leadership turned the tide, transforming Early's stunning morning victory into afternoon disaster. Early retreated up the

Valley under sharp criticism of his generalship, while President Abraham Lincoln rode the momentum of Sheridan's

victories in the Valley and Sherman's successes in the Atlanta

campaign to re-election in November. A campaign slogan of the time duly noted that the ``Early'' bird had gotten its ``Phil.''

Early attempted a last offensive in mid-November, advancing to Middletown. But his weakened cavalry was defeated by Union cavalry at

Newtown (Stephens City) and Ninevah, forcing him to withdraw his infantry. The Union cavalry now so overpowered

his own that Early could not maneuver offensively against Sheridan.

On November 22, the cavalry fought at Rude's Hill, and on December 12, a second Union cavalry raid was turned back at Lacey

Springs, ending active operations for the winter season. The winter was disastrous for the Confederate army, which was no

longer able to sustain itself on the produce of the devastated Valley. Cavalry and infantry were returned to Lee's army at

Petersburg or dispersed to feed and forage for themselves.

Riding through sleet on March 2, 1865, Custer's and Brig. Gen. Thomas

Devin's cavalry divisions advanced from Staunton, arriving near Waynesboro in the early afternoon. There, they found Early's small army, consisting of a

remnant of Brig. Gen. Gabriel Wharton's division and some artillery units. Early presented a brave front although the South

River was to his rear, but in a few hours, the war for the Shenandoah Valley was over. Early's

army fled before the Union cavalry, scattering up the mountainside. Early escaped with a few of his aides, riding away from

his last battle with no forces left to contest Union control of the Shenandoah Valley.

With the Confederate threat in the Valley eliminated, General Sheridan

led his cavalry overland to Petersburg to participate in the final campaign of the war, Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, in Virginia. On April 9, 1865, after collapse of

the Petersburg lines and a harried retreat, General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House.

Sources: National Park Service; Official Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies; Maps by Hal Jespersen located online cwmaps.com.

Recommended Reading: The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864 (McFarland & Company). Description: A

significant part of the Civil War was fought in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, especially in 1864. Books and articles

have been written about the fighting that took place there, but they generally cover only a small period of time and focus

on a particular battle or campaign. Continued below.

This work covers

the entire year of 1864 so that readers can clearly see how one event led to another in the Shenandoah Valley and turned once-peaceful

garden spots into gory battlefields. It tells the stories of the great leaders, ordinary men, innocent civilians, and armies

large and small taking part in battles at New Market, Chambersburg, Winchester, Fisher’s

Hill and Cedar Creek, but it primarily tells the stories of the soldiers, Union and Confederate,

who were willing to risk their lives for their beliefs. The author has made extensive use of memoirs, letters and reports

written by the soldiers of both sides who fought in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864.

Advance to:

Recommended

Reading: From Winchester to Cedar Creek: The Shenandoah Campaign

of 1864. Amazon.com Review: Virginia's Shenandoah Valley was a crucial avenue for Confederate armies

intending to invade Northern states during the Civil War. Running southwest to northeast, it "pointed, like a giant's lance,

at the Union's heart, Washington, D.C.,"

writes Jeffry Wert. It was also "the granary of the Confederacy," supplying the food for much of Virginia. Both sides long understood its strategic importance, but not until the fall of

1864 did Union troops led by Napoleon-sized cavalry General Phil Sheridan (5'3", 120 lbs.) finally seize it for good. He defeated

Confederate General Jubal Early at four key battles that autumn. Continued below…

In addition

to a narrative of the campaign (featuring dozens of characters, including General George Custer and future president Rutherford

B. Hayes), this book is a study of command. Both Sheridan and Early were capable military leaders, though

each had flaws. Sheridan tended to make mistakes before battles,

Early during them. Wert considers Early the better general, but admits that few could match the real-time decision-making

and leadership skills of Sheridan once the bullets started

flying: "When Little Phil rode onto the battlefield, he entered his element." Early was a bold fighter, but lacked the skills

necessary to make up for his disadvantage in manpower. At Cedar Creek, the climactic battle of the 1864 Shenandoah campaign,

Early "executed a masterful offensive against a numerically superior opponent, only to watch it result in ruin." With more

Confederate troops on the scene, history might have been different. Wert relates the facts of what actually happened with

his customary clarity and insightful analysis.

Recommended

Reading: Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign, by Peter Cozzens (Civil War America)

(Hardcover). Description: In the spring of 1862, Federal troops under the command of General George B. McClellan launched

what was to be a coordinated, two-pronged attack on Richmond

in the hope of taking the Confederate capital and bringing a quick end to the Civil War. The Confederate high command tasked

Stonewall Jackson with diverting critical Union resources from this drive, a mission Jackson fulfilled by repeatedly defeating

much larger enemy forces. His victories elevated him to near iconic status in both the North and the South and signaled a

long war ahead. One of the most intriguing and storied episodes of the Civil War, the Valley Campaign has heretofore only

been related from the Confederate point of view. Continued below…

With Shenandoah

1862, Peter Cozzens dramatically and conclusively corrects this shortcoming, giving equal attention to both Union and Confederate perspectives. Based on a multitude of primary sources, Cozzens's groundbreaking

work offers new interpretations of the campaign and the reasons for Jackson's success. Cozzens also demonstrates instances in which the

mythology that has come to shroud the campaign has masked errors on Jackson's part. In addition, Shenandoah 1862 provides the first detailed

appraisal of Union leadership in the Valley Campaign, with some surprising conclusions. Moving seamlessly between tactical

details and analysis of strategic significance, Cozzens presents the first balanced, comprehensive account of a campaign that

has long been romanticized but never fully understood. Includes 13 illustrations and 13 maps. About the Author: Peter Cozzens

is an independent scholar and Foreign Service officer with the U.S. Department of State. He is author or editor of nine highly

acclaimed Civil War books, including The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth

(from the University

of North Carolina Press).

Recommended

Reading: Stonewall in the Valley: Thomas J.

Stonewall Jackson's Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Spring 1862. Description: The Valley Campaign conducted by Maj. Gen. Thomas

J. "Stonewall" Jackson has long fascinated those interested in the American Civil War as well as general students of military

history, all of whom still question exactly what Jackson

did in the Shenandoah in 1862 and how he did it. Since Robert G. Tanner answered many questions in the first edition of Stonewall

in the Valley in 1976, he has continued to research the campaign. This edition offers new insights on the most significant

moments of Stonewall's Shenandoah triumph. Continued below…

About the Author:

Robert G. Tanner is a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute. Tanner is a native of Southern California, he now lives

and practices law in Atlanta, Georgia. He has studied

and lectured on the Shenandoah Valley Campaign for more than twenty-five years.

Recommended

Reading: The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1862, by Gary W. Gallagher. Description: In eight new essays, contributors to this volume explore the

Shenandoah Valley campaign, best known for its role in establishing Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's reputation as a Confederate

hero. In early 1862, Union troops under George B. McClellan had arrived within range of Richmond and threatened to take the Confederate

capital. Robert E. Lee ordered Jackson to march north through

the Shenandoah Valley, hoping to tie down Federal forces

that might otherwise reinforce McClellan's troops. The strategy worked, and for two months the Confederates evaded and harassed

their Union pursuers. Jackson's

speed and audacity boosted plummeting Southern morale, and he emerged from the Valley as the Confederacy's greatest military

idol. Continued below…

Contributors

address questions of military leadership, strategy and tactics, the campaign's political and social impact, and the ways in

which participants' memories of events differed from what is revealed in the historical sources. In the process, they offer

valuable insights into one of the Confederacy's most famous generals, those who fought with him and against him, the campaign's

larger importance in the context of the war, and the complex relationship between history and memory. Contributors include

Jonathan M. Berkey, Keith S. Bohannon, Peter S. Carmichael, Gary W. Gallagher, A. Cash Koeniger, R. E. L. Krick, Robert K.

Krick, and William J. Miller. About the Author: Gary W. Gallagher is John L. Nau III Professor of History at the University of Virginia. He is author, most recently, of Lee and His Army

in Confederate History.

Recommended Reading: Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Description: Jubal A. Early’s disastrous battles in the Shenandoah Valley

ultimately resulted in his ignominious dismissal. But Early’s lesser-known summer campaign of 1864, between his raid

on Washington and Phil Sheridan’s renowned fall campaign, had a significant impact on the political and military landscape

of the time. By focusing on military tactics and battle history in uncovering the facts and events of these little-understood

battles, Scott C. Patchan offers a new perspective on Early’s contributions to the Confederate war effort—and

to Union battle plans and politicking. Patchan details the previously unexplored battles at Rutherford’s Farm and Kernstown

(a pinnacle of Confederate operations in the Shenandoah Valley) and examines the campaign’s

influence on President Lincoln’s reelection efforts. Continued below…

He also provides

insights into the personalities, careers, and roles in Shenandoah of Confederate General John C. Breckinridge, Union general

George Crook, and Union colonel James A. Mulligan, with his “fighting Irish” brigade from Chicago.

Finally, Patchan reconsiders the ever-colorful and controversial Early himself, whose importance in the Confederate military

pantheon this book at last makes clear. About the Author: Scott C. Patchan, a Civil War battlefield guide and historian, is

the author of Forgotten Fury: The Battle of Piedmont, Virginia, and a consultant and contributing writer for Shenandoah, 1862.

Review

"The author's

descriptions of the battles are very detailed, full or regimental level actions, and individual incidents. He bases the accounts

on commendable research in manuscript collections, newspapers, published memoirs and regimental histories, and secondary works.

The words of the participants, quoted often by the author, give the narrative an immediacy. . . . A very creditable account

of a neglected period."-Jeffry D. Wert, Civil War News (Jeffry D. Wert Civil War News 20070914)

"[Shenandoah

Summer] contains excellent diagrams and maps of every battle and is recommended reading for those who have a passion for books

on the Civil War."-Waterline (Waterline 20070831)

"The narrative

is interesting and readable, with chapters of a digestible length covering many of the battles of the campaign."-Curled Up

With a Good Book (Curled Up With a Good Book 20060815)

"Shenandoah

Summer provides readers with detailed combat action, colorful character portrayals, and sound strategic analysis. Patchan''s

book succeeds in reminding readers that there is still plenty to write about when it comes to the American Civil War."-John

Deppen, Blue & Grey Magazine (John Deppen Blue & Grey Magazine 20060508)

"Scott C. Patchan

has solidified his position as the leading authority of the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign with his outstanding campaign

study, Shenandoah Summer. Mr. Patchan not only unearths this vital portion of the campaign, he has brought it back to life

with a crisp and suspenseful narrative. His impeccable scholarship, confident analyses, spellbinding battle scenes, and wonderful

character portraits will captivate even the most demanding readers. Shenandoah Summer is a must read for the Civil War aficionado

as well as for students and scholars of American military history."-Gary Ecelbarger, author of "We Are in for It!": The First

Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862 (Gary Ecelbarger 20060903)

"Scott Patchan

has given us a definitive account of the 1864 Valley Campaign. In clear prose and vivid detail, he weaves a spellbinding narrative

that bristles with detail but never loses sight of the big picture. This is a campaign narrative of the first order."-Gordon

C. Rhea, author of The Battle of the Wilderness: May 5-6, 1864 (Gordon C. Rhea )

"[Scott Patchan]

is a `boots-on-the-ground' historian, who works not just in archives but also in the sun and the rain and tall grass. Patchan's

mastery of the topography and the battlefields of the Valley is what sets him apart and, together with his deep research,

gives his analysis of the campaign an unimpeachable authority."-William J. Miller, author of Mapping for Stonewall and Great

Maps of the Civil War (William J. Miller)

|