|

"The singular purpose of the soldier was to fight a battle and win."

Life of the American Civil War Soldier

"The odds of dying far outweighed the odds of surviving the

four year Civil War."

The average American Civil War (1861-1865) soldier was 5'8'' and weighed 143 lbs. 1 in 65 died in combat, 1 in 10 was wounded in combat, and 1 in 13

died from disease. The average age of the soldier was 25. In the Union Army, it is estimated that 100,000 soldiers were less

than 15 years old. It is believed that the youngest soldier wounded in combat was William

Black, age 11 (almost 12). He was wounded in his left arm. Drummer boys were as young as 9 years. And some regiments, unknowingly,

recruited female combatants.

The combat

fatalities, horrors of a prison camp, diseases (including mumps, measles, smallpox, influenza, malaria, typhoid, dysentery,

cholera, chronic diarrhea, gangrene, tuberculosis, pneumonia, yellow fever, and venereal diseases), wounds (lack of medication and medical care), forced marches, no shoes and inadequate clothing, harsh winters

and frost bite, heat stroke receptive summers, sleep deprivation, and very little food and water took a massive toll

on the soldiers of the Confederate Army.

Because of medical procedures of the

era, thousands of soldiers died of gangrene and staphylococcus (staph infections).

Scurvy, a disease caused

by lack of Vitamin C, was common due to the absence of fresh fruits and vegetables, and, with weakened immune systems,

soldiers easily succumbed to it. It was common for the soldier to experience weeks or

months without bathing. Poor hygiene, such as drinking water that had been contaminated with human feces, was a serious problem

that plagues both armies. To better relate to the soldier of the conflict, imagine each of the five

senses pushed to extremes month after month and year after year. The men, and boys, had often been told that the war would

be a quick one and that it should be over in one to three months. This was the "soldier's life."

Now colonel,

for the honor of the Good Old North State, forward! —Brigadier General James Johnston Pettigrew at

the Battle of Gettysburg on July 3, 1863

Although regiments often sustained 25% casualties in a single battle, the high

casualty rate would occur battle after battle. And while comrade and kin would fall during

the many battles, the army would continue to move from battlefield to battlefield. The regiment of the war

was raised with some 1,000 men, but in 1865 the majority had been reduced to less than 100. The odds of dying

far outweighed the odds of surviving the American Civil War.

| The life of the American Civil War soldier |

|

| Daily life of the Civil War soldier while in camp |

I

am not as brave as I thought I was. I never wanted out of a place as bad in my life. The balls hurled, the shells sang, and

the grape shot rattled. I want in no more battles. —Captain Alfred W. Bell, Company B, 39th North Carolina Infantry, after the Battle of Stones River

The soldier experienced various traumatic stressors such as witnessing death or dismemberment, handling dead bodies, traumatic loss of

comrades, realizing imminent death, and killing others and being helpless to prevent others' deaths. Rare soldiers' letters allow the reader the most detailed insight to their experiences, describing even intimate and personal experiences,

such as diseases, privation, wounds, loneliness, exhaustion, heartache, and even the

injuries that were slowing killing the soldier. As the Union and Confederate soldiers tramped from battlefield to battlefield

during the conflict's four years, many held letters from family members and sweethearts. From comforting and loving words

to details of the untenable conditions on the home front, soldiers, longing for hearth and home, continued to embrace

and reread the same letters with hopes of soon arriving at the finality of a war that many said would be over in just

90 days.

"Diseases

and Napoleonic Tactics were the contributing factors for the high casualties during the American Civil War."

It was common practice

for family, friends and neighbors to enlist in the same locally raised unit. The reason that any given soldier

fought in all those battles was because he didn't want to be called a coward, show the white feather, says many present-day

scholars, but this reasoning is incorrect, it is flawed.

The soldier or Marine did not go through hell and back on the battlefield because he wanted to avoid being called

a coward. Men stood, held their ground, and fought as soldiers then as they do for the same motivating factor now. Ask

anyone who has been in combat or battle, why did you do it? The answer through history has a familiar tone. I fought

for the guy next to me, I fought for my buddies, I fought for my unit. Perhaps the white feather

argument has been splashed on the pages of textbooks by historians, but it was not drawn from the real life experiences of

the men who had actually been in combat. During battle it was therefore typical for father and son to advance directly into enemy shot

and shell, making it a leading factor in the high death toll during the fight.

During the aftermath, or postwar, many suffered from the war's great destruction and devastation. Countless

veterans were riddled with diseases, wounds, destitution, and mental illnesses. Many soldiers recovering from wounds were referred to as having the Old Soldier's

Disease, a term applied to soldiers addicted to pain killers. Hearing loss was common due to the horrendous

sounds associated with cannon and weaponry in combat. Furthermore, during the American Civil War,

there was no shell shock, battle fatigue, or Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) to help explain and legitimize

a mysterious condition. The aftermath witnessed tens-of-thousands of homeless veterans.

The veteran either had no home to return to or a disability prevented him from enjoying life's basic tasks and responsibilities. Union soldiers and veterans didn't

receive the Department of Veterans Affairs' benefits and assistance, because it wasn't created until the

twentieth century. (See also Shook over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War .) Family and friends were all the hope and help that many veterans had, for to fall into the hands

of the state is exactly why insane asylums boomed across the nation after the war. .) Family and friends were all the hope and help that many veterans had, for to fall into the hands

of the state is exactly why insane asylums boomed across the nation after the war.

The hardest work I have had since we got here was

standing guard duty six hours night before last. —Private John T. Jones, Company D (Orange Light Infantry), First Regiment

North Carolina Volunteers, May 8, 1861

While not in battle, drilling, or standing guard, the troops read, wrote letters to their loved ones and

played any game they could devise, including baseball, cards and boxing matches. One competition

involved racing lice or cockroaches across a strip of canvas. The

soldier's favorite beverage was coffee, but alcohol was occasionally smuggled into camp. See also The American Civil War Soldier.

"Penicillin had not been invented, so soldiers

treated venereal diseases with herbs and minerals"

| Life for the American Civil War soldiers |

|

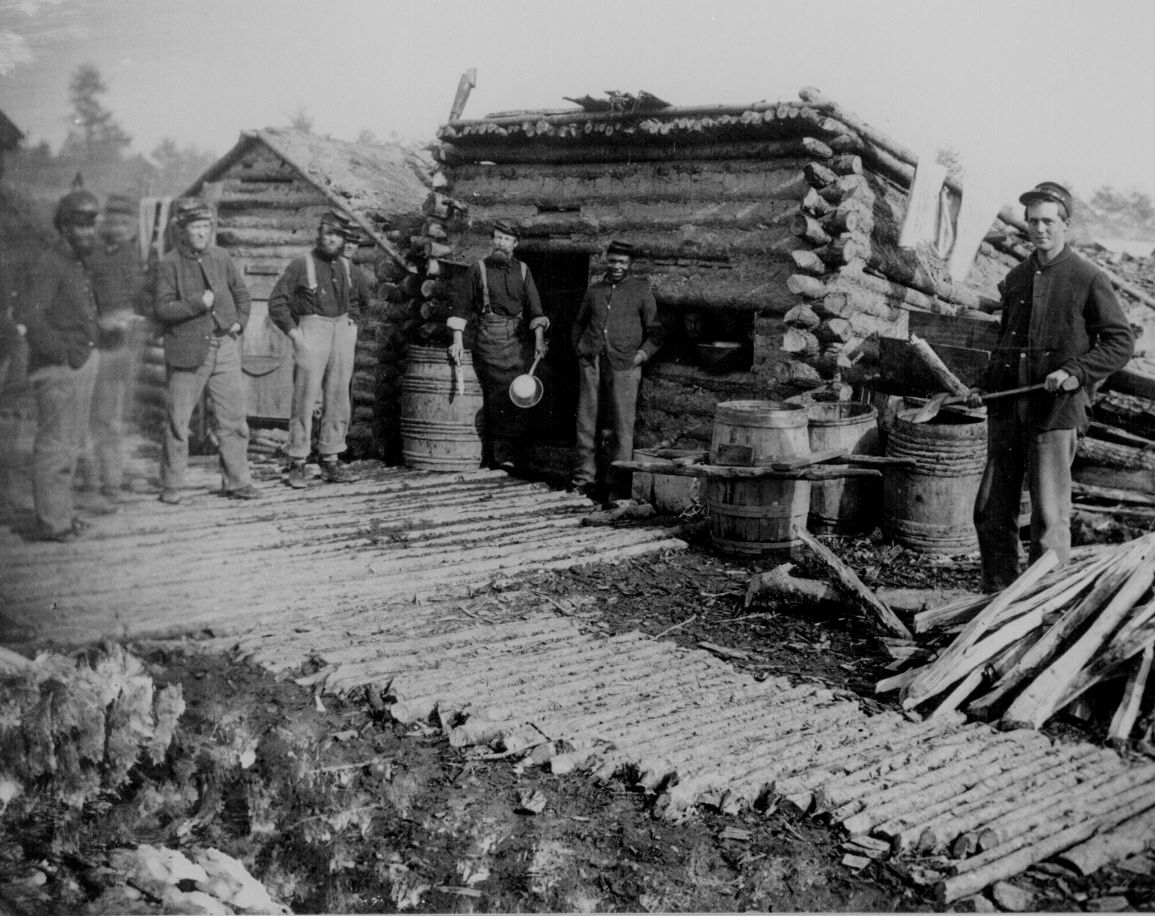

| Civil War soldiers gathering for meal at the makeshift kitchen |

Thousands of prostitutes

thronged the cities in the war zones and clustered about the camps. By 1862,

for instance, Washington,

D.C., had 450 bordellos and at least 7,500 full-time prostitutes; Richmond

was the center of prostitution in the Confederacy and had about an equal number of bordellos and

prostitutes. Venereal disease among soldiers was prevalent and largely uncontrolled. About eight percent of the soldiers in

the Union army were treated for venereal disease during the war; many cases were unreported. Penicillin had not been invented,

so soldiers treated venereal diseases with herbs and minerals. Union General Joseph "Hooker" was widely known for his endorsement

of prostitution; hence, his name is credited, associated, and synonymous with "prostitutes and prostitution."

We have a revival going on in our Regt. & it is general through the army.

Our Chaplain is doing much good. —Lieutenant Colonel William Henry Asbury

Speer, Twenty-eighth Regiment North Carolina Troops, April 28, 1863

"I would have never surrendered if

I knew that being a prisoner was worse than death."

I do not exaggerate when I say that it [Johnson's

Island] is worse than a hog pen. —Colonel Robert F. Webb, Sixth Regiment

North Carolina State Troops, February 25, 1864

Camp life as a Confederate soldier was hard, but prison

life in Camp Morton was harder. —Confederate Prisoner of War

Eighty Acres of Hell, a.k.a. Prisoner of War Camp Douglas, reveals

that the Union was more than capable of matching the Confederates atrocity-for-atrocity. While 12,000 prisoners entered Camp

Douglas, only 6,000 survived. The rest were victims of calculated cruelty, torture and neglect. And Southern soldiers were

not the only targets of this treatment--many prominent Chicago citizens were incarcerated under the banner of martial law,

unjustly convicted of imagined offenses by ruthless military tribunals. According to Official Records of the Union and Confederate armies, Series II - Vol. 8, p. 348, Confederate prisoners

were placed in condemned Union Prisoner of War Camps Douglas and Chase; they were condemned because they were

infected with smallpox. The Official Records further state that several Union officials

protested and called Camp Douglas an atrocity. However, Union prisoners of war were in equally atrocious conditions

See also Union and Confederate

Civil War Prisoner of War and Prison History: Homepage and American Civil War Prisoner of War Camps.

| Death was a reality for any Civil War soldier |

|

| American Civil War soldiers killed in battle |

"I fought in very many battles of the Confederate war

because my brother, my uncle, and all my friends had served in the same local company."

During the last months of the American Civil War, when the Lost Cause was

embraced, many Southern soldiers were unofficially promoted by their peers to fill vacancies, and it also explains

why the officially mustered out rank and grade was often times lesser than claimed in soldiers' diaries, memoirs and

papers. During the last months of the war, privates were being

unofficially appointed to the rank or grade of lieutenant to fill the void. Concurrently, some Confederate commanders were destroying all, or what remained, of the regimental

records. Said conditions also make it difficult for Civil War researchers and genealogists.

"I apprehend

that if all living Union soldiers were summoned to the witness stand, every one of them would testify that it was the preservation

of the American Union and not the destruction of Southern slavery that induced him to volunteer at the call of his Country.

As for the South, it is enough to say that perhaps eighty percent of her armies were neither slave-holders, nor had the remotest

interest in the institution...both sides fought and suffered for liberty as bequeathed by the Fathers--the one for liberty

in the union of the States, the other for liberty in the independence of the States." Reminiscences of the Civil War, by John

B. Gordon, Maj. Gen. CSA

(General

Gordon was shot 5 times during the Battle of Antietam but did not die until January 9, 1904. Regarding General John Gordon, President Theodore Roosevelt

stated, "A more gallant, generous, and fearless gentleman and soldier has not been seen by our Country.")

The Aftermath and Reconstruction proved that the scars from the American Civil War deeply affected veterans and civilians for years.

(Sources and related reading below.)

Recommended Reading: The Fighting Men of

the Civil War, by William C. Davis (Author), Russ A. Pritchard (Author). Description: "A must for any

Civil War library!" The sweeping histories of the War Between the States often overlook the men in whose blood that history

was written. This account goes a long way toward redressing the balance in favor of the men in the ranks. The reader follows

the soldiers from enlistment and training to campaigning. Attention is also given to oft-forgotten groups such as the sailors

and black troops. Continued below...

No effort has been spared to include rare war era photographs and

color photos of rare artifacts. Engagingly written by William C. Davis, the author of more than thirty books on the American

Civil War. Award winning author and historian James M. McPherson states: "The most readable, authoritative, and

beautifully designed illustrated history of the American Civil War."

Recommended Reading:

Eyewitness to the Civil War (Hardcover) (416 pages) (National Geographic)

(November 21, 2006). Description: At once an informed overview for general-interest readers and a superb resource for serious

buffs, this extraordinary, gloriously illustrated volume is sure to become one of the fundamental books in any Civil War library.

Its features include a dramatic narrative packed with eyewitness accounts and hundreds of rare photographs, pictures,

artifacts, and period illustrations. Evocative sidebars, detailed maps, and timelines add to the reference-ready quality of

the text. Continued below...

From John Brown's raid to

Reconstruction, Eyewitness to the Civil War presents a clear, comprehensive discussion that addresses every military, political,

and social aspect of this crucial period. In-depth descriptions of campaigns and battles in all theaters of war are accompanied

by a thorough evaluation of the nonmilitary elements of the struggle between North and South. In their own words, commanders

and common soldiers in both armies tell of life on the battlefield and behind the lines, while letters from wives, mothers,

and sisters provide a portrait of the home front. More than 375 historical photographs, portraits, and artifacts—many

never before published—evoke the era's flavor; and detailed maps of terrain and troop movements make it easy to follow

the strategies and tactics of Union and Confederate generals as they fought through four harsh years of war. Includes captivating

rare photos of soldiers to the realistic firsthand battlefield photo. Photoessays on topics ranging from the everyday lives

of soldiers to the dramatic escapades of the cavalry lend a breathtaking you-are-there feeling, and an inclusive appendix

adds even more detail to what is already a magnificently meticulous history.

Recommended Reading:

The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (444

pages) (Louisiana State University Press) (Updated edition: November 2007) Description: The Life of Johnny Reb does not merely

describe the battles and skirmishes fought by the Confederate foot soldier. Rather, it provides an intimate history of a soldier's

daily life--the songs he sang, the foods he ate, the hopes and fears he experienced, the reasons he fought. Wiley examined

countless letters, diaries, newspaper accounts, and official records to construct this frequently poignant, sometimes humorous

account of the life of Johnny Reb. In a new foreword for this updated edition, Civil War expert James I. Robertson, Jr., explores

the exemplary career of Bell Irvin Wiley, who championed the common folk, whom he saw as ensnared in the great conflict of

the 1860s. Continued below...

About

Johnny Reb:

"A Civil War

classic."--Florida Historical Quarterly

"This book

deserves to be on the shelf of every Civil War modeler and enthusiast."--Model Retailer

"[Wiley] has

painted with skill a picture of the life of the Confederate private. . . . It is a picture that is not only by far the most

complete we have ever had but perhaps the best of its kind we ever shall have."--Saturday Review of Literature

Recommended

Reading:

Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (488 pages) (Louisiana State University Press). Description: This fascinating social history reveals that while the Yanks and the Rebs fought for very different causes, the men

on both sides were very much the same. "This wonderfully interesting book is the finest memorial the Union soldier is ever

likely to have. . . . [Wiley] has written about the Northern troops with an admirable objectivity, with sympathy and understanding

and profound respect for their fighting abilities. He has also written about them with fabulous learning and considerable

pace and humor.

Editor's Pick: Co.

Aytch: A Confederate Memoir of the Civil War. Description: Of the 120 men who enlisted in "Company H"

(Or Co. Aytch as he calls it) in 1861, Sam Watkins was one of only seven alive when General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee

surrendered to General William Tecumseh Sherman in North Carolina

in April, 1865. Of the 1,200 men who fought in the First Tennessee, only 65 were left to be paroled on that day. "Co. Aytch: A Confederate Memoir of the Civil War" is heralded by many historians as one of the best

war memoirs written by a common soldier of the field. Sam R. Watkin's writing style in "Co Aytch" is quite engaging and skillfully

captures the pride, misery, glory, and horror experienced by the common foot soldier. Continued below…

About the Author: Samuel "Sam"

Rush Watkins (June 26, 1839 - July 20, 1901) was a noted Confederate soldier during the American Civil War. He is known today

for his memoir Company Aytch: Or, a Side Show of the Big Show, often heralded as one of the best primary sources about the

common soldier's Civil War experience. Watkins was born on June 26, 1839 near Columbia, Maury County, Tennessee, and received his formal education at Jackson

College in Columbia.

He originally enlisted in the "Bigby Greys" of the 3rd Tennessee Infantry in Mount Pleasant, Tennessee, but transferred shortly

thereafter to the First Tennessee Infantry, Company H (the "Maury Greys") in the spring of 1861. Watkins faithfully served

throughout the duration of the War, participating in the battles of Shiloh, Corinth, Perryville,

Murfreesboro (Stones River),

Shelbyville, Chattanooga, Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, Resaca,

Adairsville, Kennesaw Mountain (Cheatham

Hill), New Hope Church, Zion

Church, Kingston, Cassville, Atlanta,

Jonesboro, Franklin, and Nashville.

Of the 120 men who enlisted in "Company H" in 1861, Sam Watkins was one of only seven alive when General Joseph E. Johnston's

Army of Tennessee surrendered to General William Tecumseh Sherman in North Carolina

April, 1865. Of the 1,200 men who fought in the First Tennessee, only 65 were left to be paroled on that day. Soon after the

war ended, Watkins began writing his memoir, entitled "Company Aytch: Or, a Side Show of the Big Show". It was originally

serialized in the Columbia, Tennessee

Herald newspaper. "Co. Aytch" was published in a first edition of 2,000 in book form in 1882. "Co. Aytch" is heralded by many

historians as one of the best war memoirs written by a common soldier of the field. Sam's writing style is quite engaging

and skillfully captures the pride, misery, glory, and horror experienced by the common foot soldier. Watkins is often featured

and quoted in Ken Burns' 1990 documentary titled The Civil War. Watkins died on July 20, 1901 at the age of sixty-two in his

home in the Ashwood Community. He was buried with full military honors by the members of the Leonidas Polk Bivouac, United

Confederate Veterans, in the cemetery of the Zion Presbyterian Church near Mount

Pleasant, Tennessee.

Editor's Picks and Recommended

Reading for "The American Civil War Soldier; Life as a Civil War Soldier"

Sources: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Walter Clark,

Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-1865; National Park Service: American

Civil War; Weymouth T. Jordan and Louis H. Manarin, North Carolina Troops, 1861-1865; D. H. Hill, Confederate Military

History Of North Carolina: North Carolina In The Civil War, 1861-1865; Library of Congress; North Carolina Office of Archives

and History; North Carolina Museum of History; State Library of North Carolina; North Carolina Department of Cultural

Resources; North Carolina Department of Agriculture; National Archives and Records Administration; and Tennessee State Library

and Archives.

|