|

Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens (January 17, 1781) was a decisive victory by American

Revolutionary forces under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, in the Southern campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It

was a turning point in the reconquest of South Carolina from the British.

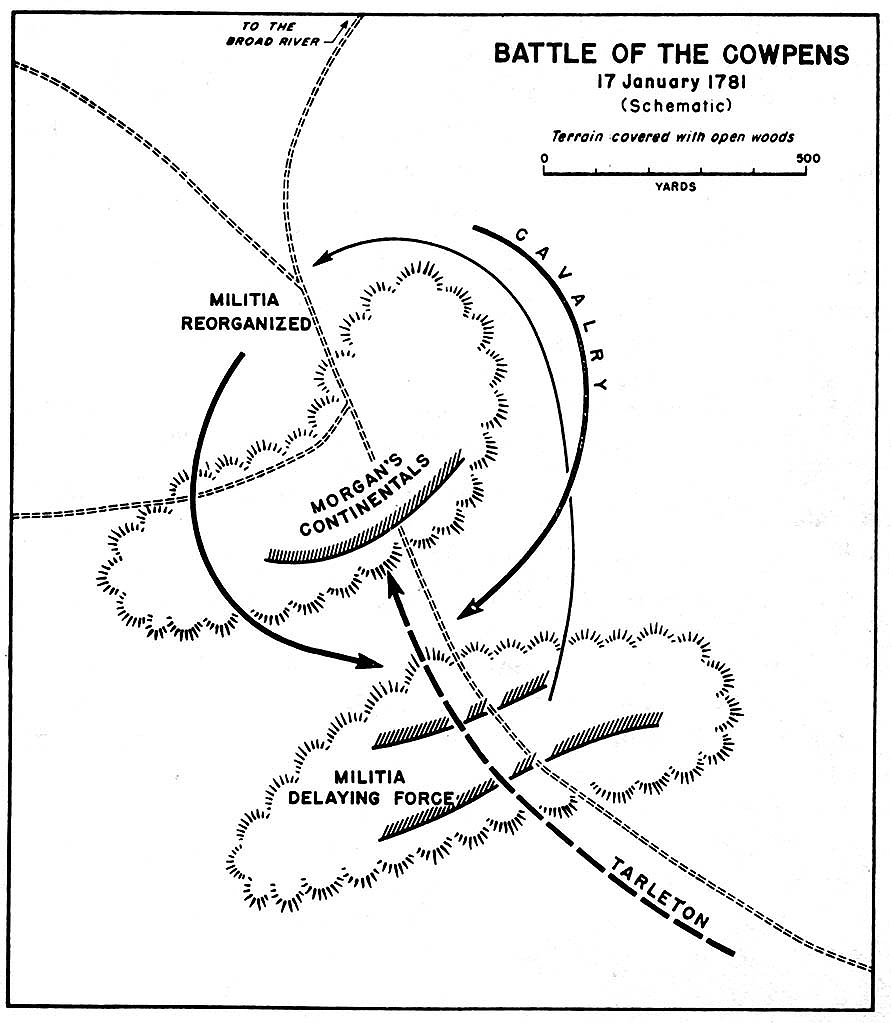

| Battle of Cowpens Map |

|

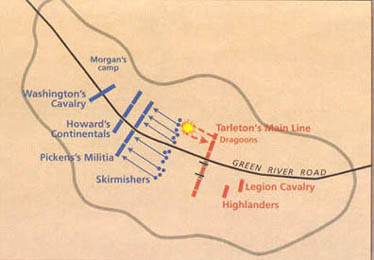

| Cowpens Battlefield Map |

(About) Battle of Cowpens 17 January 1781. Right flank (cavalry) of Lt.

Col. William Washington and (left flank) the militia returned to enfilade.

| Battle of Cowpens Map |

|

| Cowpens Revolutionary War Map |

The Battle of Cowpens1, January 17, 1781,

took place in the latter part of the Southern Campaign of the American Revolution and of the Revolution itself. It became

known as the turning point of the war in the South, part of a chain of events leading to Patriot victory at Yorktown2

The Cowpens victory was one over a crack British regular army3 and brought together strong armies

and leaders who made their mark on history.

From the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge4 on, the

British had made early and mostly futile efforts in the South, including a failed naval expedition to take Charleston in 1776.

Such victories boosted Patriot morale and blunted British efforts, but, by 1779-80, with stalemate in the North, British strategists

again looked south. They came south for a number of reasons, primarily to assist Southern Loyalists5

and help them regain control of colonial governments, and then push north, to crush the rebellion6.

They estimated that many of the population would rally to the Crown.

In 1779-80, British redcoats indeed came South en masse, capturing

first, Savannah7 and then Charleston8 and Camden

8A in South Carolina, in the process, defeating and capturing much of the Southern Continental

Army9. Such victories gave the British confidence they would soon control the entire South, that

Loyalists would flock to their cause. Conquering these population centers, however, gave the British a false sense of victory

they didn’t count on so much opposition in the backcountry10. Conflict in the backcountry,

to their rear, turned out to be their Achilles’ heel.

The Southern Campaign, especially in the backcountry, was essentially a civil

war as the colonial population split between Patriot and Loyalist. Conflict came, often pitting neighbor against neighbor

and re-igniting old feuds and animosities. Those of both sides organized militia, often engaging each other. The countryside

was devastated, and raids and reprisals were the order of the day.

Into this conflict, General George Washington sent the very capable Nathanael

Greene to take command of the Southern army. Against military custom, Greene, just two weeks into his command, split his army,

sending General Daniel Morgan southwest of the Catawba River to cut supply lines and hamper British operations in the backcountry,

and, in doing so "spirit up the people". General Cornwallis, British commander in the South, countered Greene’s move

by sending Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton to block Morgan’s actions. Tarleton was only twenty-six, but he was

an able commander, both feared and hated – hated especially for his victory at the Waxhaws.11

There, Tarleton was said to have continued the fight against remnants of the Continental Army trying to surrender. His refusal,

tradition says, of offering no quarter, led to the derisive term "Tarleton’s Quarter".

These events set the stage for the Battle of Cowpens. On January 12, 1781,

Tarleton's scouts located Morgan’s army at Grindal’s Shoals on the Pacolet River12

in South Carolina’s backcountry and thus began an aggressive pursuit. Tarleton, fretting about heavy rains and flooded

rivers, gained ground as his army proceeded toward the flood-swollen Pacolet. As Tarleton grew closer, Morgan retreated north

to Burr’s Mill on Thicketty Creek.13 On January 16, with Tarleton reported to have crossed

the Pacolet and much closer than expected, Morgan and his army made a hasty retreat, so quickly as to leave their breakfast

behind. Soon, he intersected with and traveled west on the Green River Road. Here, with the flood-swollen Broad River14

six miles to his back, Morgan decided to make a stand at the Cowpens, a well-known crossroads and frontier pasturing ground.

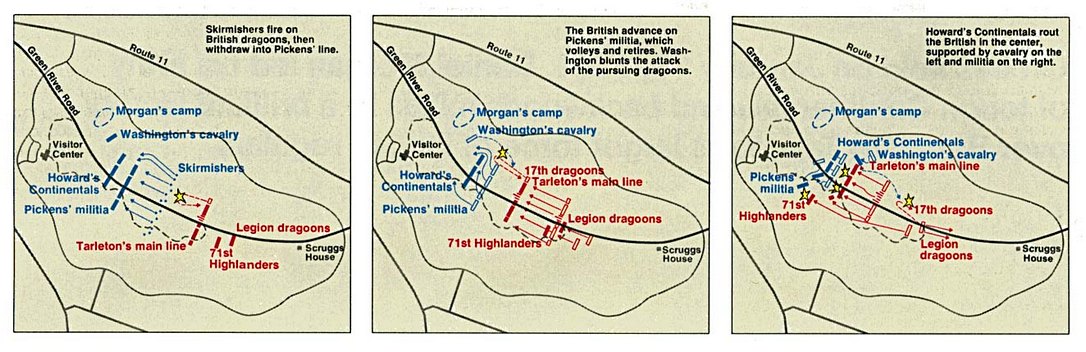

| American Revolutionary War Map |

|

| Phases of Battle of Cowpens during the Revolutionary War |

(About) American Skirmishers, Militia, and Continentals halt British advance.

The term "cowpens"15, endemic to such South Carolina

pastureland and associated early cattle industry, would be etched in history. The field itself was some 500 yards long and

just as wide, a park-like setting dotted with trees, but devoid of undergrowth, having been kept clear by cattle grazing in

the spring on native grasses and peavine16.

There was forage17 at the Cowpens for horses,

and evidence of free-ranging cattle for food. Morgan, too, since he had learned of Tarleton’s pursuit, had spread the

word for militia18 units to rendezvous at the Cowpens. Many knew the geography some were Overmountain

men who had camped at the Cowpens on their journey to the Battle of Kings Mountain.19 Camp was made in a swale between two small hills, and through the night Andrew Pickens’

militia drifted into camp. Morgan moved among the campfires and offered encouragement; his speeches to militia and Continentals

alike were command performances. He spoke emotionally of past battles, talked of the battle plan, and lashed out against the

British. His words were especially effective with the militia the "Old Waggoner"20 of French and

Indian War days and the hero of Saratoga21, spoke their language. He knew how to motivate them

even proposing a competition of bravery between Georgia and Carolina units. By the time he was through, one soldier observed

that the army was "in good spirits and very willing to fight". But, as one observed, Morgan hardly slept a wink that night.

Dawn at the Cowpens on January 17, 1781, was clear and bitterly cold. Morgan,

his scouts bearing news of Tarleton’s approach, moved among his men, shouting, "Boys, get up! Benny's22 coming! Tarleton, playing catch up, and having marched his army

since two in the morning, ordered formation on the Green River Road for the attack. His aggressive style was made even now

more urgent, since there were rumors of Overmountain men on the way, reminiscent of events at Kings Mountain. Yet he was confident

of victory: he reasoned he had Morgan hemmed in by the Broad, and the undulating park-like terrain was ideal for his dragoons23.

He thought Morgan must be desperate, indeed, to have stopped at such a place. Perhaps Morgan saw it differently: in some past

battles, Patriot militia had fled in face of fearsome bayonet charges – but now the Broad at Morgan’s back could

prevent such a retreat. In reality, though, Morgan had no choice – to cross the flood-swollen Broad risked having his

army cut down by the feared and fast-traveling Tarleton.

Tarleton pressed the attack head on, his line extending across the meadow,

his artillery in the middle, and fifty Dragoons on each side. It was as if Morgan knew he would make a frontal assault –

it was his style of fighting. To face Tarleton, he organized his troops into three lines. First, out front and hiding behind

trees were selected sharpshooters. At the onset of battle they picked off numbers of Tarleton’s Dragoons, traditionally

listed as fifteen24, shooting especially at officers, and warding off an attempt to gain initial

supremacy. With the Dragoons in retreat, and their initial part completed, the sharpshooters retreated 150 yards or more back

to join the second line, the militia commanded by Andrew Pickens. Morgan used the militia well, asking them to get off two

volleys and promised their retreat to the third line made up of John Eager Howard's25 Continentals,

again close to 150 yards back. Some of the militia indeed got off two volleys as the British neared, but, as they retreated

and reached supposed safety behind the Continental line, Tarleton sent his feared Dragoons after them. As the militia dodged

behind trees and parried saber slashes with their rifles, William Washington's26 Patriot cavalry thundered onto the field of battle, seemingly,

out of nowhere. The surprised British Dragoons, already scattered and sensing a rout, were overwhelmed, and according to historian

Babits, lost eighteen men in the clash. As they fled the field, infantry on both sides fired volley after volley. The British

advanced in a trot, with beating drums, the shrill sounds of fifes, and shouts of halloo. Morgan, in response, cheering his

men on, said to give them the Indian halloo back. Riding to the front, he rallied the militia, crying out, "form, form, my

brave fellows! Old Morgan was never beaten!"

Now Tarleton’s 71st Highlanders27, held

in reserve, entered the charge toward the Continental line, the wild wail of bagpipes adding to the noise and confusion. A

John Eager Howard order for the right flank to face slightly right to counter a charge from that direction, was, in the noise

of battle, misunderstood as a call to retreat. As other companies along the line followed suite, Morgan rode up to ask Howard

if he were beaten. As Howard pointed to the unbroken ranks and the orderly retreat and assured him they were not, Morgan spurred

his horse on and ordered the retreating units to face about, and then, on order, fire in unison. The firing took a heavy toll

on the British, who, by that time had sensed victory and had broken ranks in a wild charge. This event and a fierce Patriot

bayonet charge in return broke the British charge and turned the tide of battle. The re-formed militia and cavalry re-entered

the battle, leading to double envelopment28 of the British, perfectly timed. British infantry

began surrendering en masse.

Tarleton and some of his army fought valiantly on; others refused his orders

and fled the field. Finally, Tarleton, himself, saw the futility of continued battle, and with a handful of his men, fled

from whence he came, down the Green River Road. In one of the most dramatic moments of the battle, William Washington, racing

ahead of his cavalry, dueled hand-to-hand with Tarleton and two of his officers. Washington’s life was saved only when

his young bugler29 fired his pistol at an Englishman with raised saber. Tarleton and his remaining

forces galloped away to Cornwallis’ camp. Stragglers from the battle were overtaken, but Tarleton escaped to tell the

awful news to Cornwallis.

The battle was over in less than an hour. It was a complete victory for the

Patriot force. British losses were staggering: 110 dead, over 200 wounded and 500 captured. Morgan lost only 12 killed and

60 wounded, a count he received from those reporting directly to him.

Knowing Cornwallis would come after him, Morgan saw to it that the dead were

buried – the legend says in wolf pits -- and headed north with his army. Crossing the Broad at Island Ford30,

he proceeded to Gilbert Town31, and, yet burdened as he was by the prisoners, pressed swiftly

northeastward toward the Catawba River, and some amount of safety. The prisoners were taken via Salisbury32

on to Winchester, Virginia. Soon Morgan and Greene reunited and conferred, Morgan wanting to seek protection in the mountains

and Greene wanting to march north to Virginia for supplies. Greene won the point, gently reminding Morgan that he was in command.

Soon after Morgan retired from his duty because of ill health— rheumatism, and recurring bouts of malarial fever.

Now it was Greene and his army on the move north. Cornwallis, distressed by

the news from Cowpens, and wondering aloud how such an interior force could defeat Tarleton's crack troops, indeed came after

him. Now it was a race for the Dan River33 on the Virginia line, Cornwallis having burned his

baggage34 and swiftly pursuing Greene. Cornwallis was subsequently delayed by Patriot units stationed

at Catawba River35 crossings. Greene won the race, and, in doing so, believed he had Cornwallis

where he wanted -- far from urban supply centers and short of food. Returning to Guilford Courthouse36,

he fought Cornwallis' army employing with some success, Morgan's tactics at Cowpens. At battle's end, the British were technically

the winners as Greene's forces retreated. If it could be called a victory, it was a costly one: Five hundred British lay dead

or wounded. When the news of the battle reached London, a member of the House of Commons said, "Another such victory would

ruin the British army". Perhaps the army was already ruined, and Greene's strategy of attrition was working.

Soon, Greene's strategy was evident: Cornwallis and his weary army gave up

on the Carolinas and moved on to Virginia. On October 18, 1781, the British army surrendered at Yorktown. Cowpens, in its

part in the Revolution, was a surprising victory and a turning point that changed the psychology of the entire war. Now, there

was revenge – the Patriot rallying cry Tarleton's Quarter37.

Morgan's unorthodox but tactical masterpiece had indeed "spirited up the people", not just those of the backcountry Carolinas,

but those in all the colonies. In the process, he gave Tarleton and the British a "devil of a whipping". Continued below...

Feeding the Armies

In the Revolution, Patriot and British armies often marched and fought

on empty stomachs as plans for obtaining food went awry. This was particularly true in the backcountry where food was scarce.

Examples of foraging for food and food-related problems abound. Earlier in the war, General Gates and his Southern Continentals,

on the march to Camden, subsisted on apples, peaches, and half-ripened corn. James Collins, writing about backcountry campaigns

in his Autobiography of a Revolutionary Soldier, told of eating turnips and parched corn. In one poignant example,

Battle of Cowpen's participant John Martin, recuperating from wounds in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, and beyond assistance

of the army, reported the death of his horse because he lacked money to purchase forage. In another instance, Cornwallis,

because his army was so dead tired and hungry, chose not to pursue General Greene in the aftermath of the Battle of Guilford

Courthouse. Up in Virginia, Samuel McCune was employed to drive cattle from Augusta County to Yorktown. Throughout the southern

theater of war, scouting parties on both sides would scour the country in every direction in search of food.

At Cowpens, Daniel Morgan worried about obtaining food for his men - the area

around the Pacolet River had been plundered and fought over so much, there was little to requisition. In addition, he had

horses to feed. Each militiaman had brought a horse, in addition to those of the cavalry, making the total over 450. Perhaps

that was part of Morgan's plan to stop at Cowpens - there should be some grass for the horses, even in winter, and, possibly

free-ranging calves could be found and killed for beef. Beef was indeed available: James Turner, a Spartanburg District resident

and participant in the battle, butchered beef to feed Morgan's army before and after the battle. It was reported that militia

groups constantly left camp to hunt for forage. Such were the realities of feeding the armies.

Scott Withrow, Park Ranger, National Park Service

(Glossary and bibliography listed at bottom of page)

Recommended Viewing: The History Channel Presents The Revolution (A&E) (600 minutes). Review: They came of age in a new world amid intoxicating and innovative ideas

about human and civil rights diverse economic systems and self-government. In a few short years these men and women would

transform themselves into architects of the future through the building of a new nation – “a nation unlike any

before.” From the roots of the rebellion and the signing of the Declaration of Independence to victory on the battlefield

at Yorktown

and the adoption of The United States Constitution, THE REVOLUTION tells the remarkable story of this pivotal era in history.

Venturing beyond the conventional list of generals and politicians, THE HISTORY CHANNEL® introduces the full range of individuals

who helped shape this great conflict including some of the war’s most influential unsung heroes. Continued below...

Through sweeping

cinematic recreations intimate biographical investigations and provocative political military and economic analysis the historic

ideas and themes that transformed treasonous acts against the British into noble acts of courage both on and off the battlefield

come to life in this dramatic and captivating program. This TEN HOUR DVD Features: History in the Making: The Revolution Behind-the-Scenes

Featurette; Interactive Menus; Scene Selections.

Recommended

Reading:

A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle

of Cowpens. Description: It's easy to forget that the British won most of the battles during the American

Revolution. The Americans certainly carried the day at Saratoga and Yorktown,

but they were beaten again and again by their enemy elsewhere--and often badly. So it's especially odd that the Battle of

Cowpens, fought in South Carolina on January 17, 1781, isn't

better remembered in American imagination. As author Lawrence E. Babits shows, Cowpens was the Continental troops' greatest

tactical moment--and it marked a crucial turning point in the war. Continued below...

The fight itself

was fairly brief, and the outcome lopsided--it was "a devil of a whipping," as American leader Daniel Morgan said at the time.

Babits provides a richly detailed account of the battle, including an especially good overview of the weapons and tactics

used by troops of the time. An archaeologist by training, Babits approaches Cowpens with the familiar meticulousness of his

profession; this is an important piece of scholarship on the military history of the American Revolution.

Recommended

Viewing: Cowpens: The Battle Remembered (DVD). Description:

A Tactical Masterpiece of the Revolutionary War. On January 17th, 1781 at the Battle of Cowpens, Brigadier General Daniel

Morgan changed the course of the Revolutionary War with his resounding victory over Lt. Colonel “Bloody” Banastre

Tarleton’s British redcoats. Cowpens: A Battle Remembered depicts this dramatic conflict through the remembrances of

one American militiaman who fought for Morgan. This historic event is commemorated today at Cowpens National Battlefield in

South Carolina.

Recommended Reading: Battles Of The Revolutionary War: 1775-1781 (Major Battles and Campaigns Series). Description: The Americans did not simply

outlast the British in the Revolutionary War, contends this author in a groundbreaking study, but won their independence by

employing superior strategies, tactics, and leadership. Designed for the "armchair strategist" with dozens of detailed maps

and illustrations, here is a blow-by-blow analysis of the men, commanders, and weaponry used in the famous battles of Bunker

Hill, Quebec, Trenton, Princeton, Saratoga, and Cowpens.

Recommended Reading: Kings Mountain and

Cowpens (SC): Our Victory was Complete. Description: From the rocky slopes of Kings Mountain to the plains

of Hannah's Cowpens, the Carolina backcountry hosted two of the Revolutionary War's most critical battles. On October 7, 1780,

the Battle of Kings Mountain utilized guerrilla techniques- American Overmountain Men wearing buckskin and hunting shirts

and armed with hunting rifles attacked Loyalist troops from behind trees, resulting in an overwhelming Patriot victory. Continued

below...

In January of the next year, the Battle of Cowpens saw a different strategy but a similar outcome: with

brilliant military precision, Continental Regulars, dragoons and Patriot militia executed the war's only successful double

envelopment maneuver to defeat the British. Using firsthand accounts and careful analysis of the best classic and modern scholarship

on the subject, historian Robert Brown demonstrates how the combination of both battles facilitated the downfall of General

Charles Cornwallis and led to the Patriot victory in America.

Recommended Reading: The

Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas

(Paperback). Review: Most of us are familiar with the role that North and South Carolina

played in the American Civil War: if nothing else, every grade-schooler knows the significance of the 1861 bombardment of

Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. But to popular historian

John Buchanan, "that tragedy is of far less interest than the American Revolution. The Revolution was the most important event

in American history. The Civil War was unfinished business." And the Carolinas, Buchanan

convincingly argues, were the most critical theater in that conflict, with their wild Back Country seeing "a little-known

but savage civil war far exceeding anything in the North." Continued below...

The Road to Guilford Courthouse

is no less than a tour de force of pop military scholarship, an exhaustive battle-by-battle account of the Crown's grinding

march to wrest the Carolinas

from the resourceful Rebels. Beginning with Colonel William Moultrie's valiant defense atop the palmetto ramparts of Fort Sullivan against

an outnumbering force of British men-of-war to the final "long, obstinate, and bloody" exchange at Guilford Courthouse, Buchanan

meticulously recounts each skirmish, battle, and shift of strategy in the campaign. Relying on copious primary and secondary

sources, he brings the combatants to life, from the worthy but somewhat obscure, such as Nathanael Greene, whom George Washington

considered to be his successor should he fall, to soon-to-be legends such as Francis Marion, the Swamp Fox. --Paul Hughes

Recommended Reading: With

Zeal and With Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783

(Campaigns and Commanders) (Hardcover). Description: This groundbreaking book offers a new analysis of the British Army during

the "American rebellion" at both operational and tactical levels. Continued below...

Presenting fresh insights into the speed of British tactical movements, Spring discloses how the system

for training the army prior to 1775 was overhauled and adapted to the peculiar conditions confronting it in North America. About the

Author: Matthew Spring holds a Ph.D. in

history from the University of Leeds and

teaches history at Truro School, an independent

secondary school in Cornwall, England.

Recommended Reading: The United States of Appalachia: How Southern Mountaineers Brought

Independence, Culture, and Enlightenment to America.

Description: Few places in the United States confound and fascinate Americans like Appalachia,

yet no other area has been so markedly mischaracterized by the mass media. Stereotypes of hillbillies and rednecks repeatedly

appear in representations of the region, but few, if any, of its many heroes, visionaries, or innovators are ever referenced. Continued

below…

Make no mistake,

they are legion: from Anne Royall, America's first female muckraker, to Sequoyah, a Cherokee mountaineer who invented the

first syllabary in modern times, and international divas Nina Simone and Bessie Smith, as well as writers Cormac McCarthy,

Edward Abbey, and Nobel Laureate Pearl S. Buck, Appalachia has contributed mightily to American culture — and politics.

Not only did eastern Tennessee

boast the country's first antislavery newspaper, Appalachians also established the first

District of Washington as a bold counterpoint to British rule. With humor, intelligence, and clarity, Jeff Biggers reminds

us how Appalachians have defined and shaped the United States

we know today.

Glossary

1 Battle of Cowpens – At the Cowpens, a frontier

pastureland, on January 17, 1781, Daniel Morgan led his army of tough Continentals and backwoods militia to a brilliant victory

over Banastre Tarleton’s battle-hardened force of British regulars. Located in present-day South Carolina north of Spartanburg.

2 Yorktown - On October 18, 1781, the British under General

Lord Cornwallis surrendered to American and French troops under General George Washington at Yorktown, Virginia.

3 British regular army – Regular, trained and uniformed

soldiers of the British Army, as distinguished from Loyalist (Tory) militia.

4 Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge – On February

27, 1777, patriot militia defeated a larger force of Loyalists. The battle was crucial because it ended royal authority in

North Carolina and delayed a full-scale British invasion of the South.

5 Southern Loyalists – Those of the southern colonial

population remaining loyal to the Crown. Also referred to as Tories.

6 rebellion – The British term for the American

Revolution. Those involved were termed "rebels" by the British.

7 Savannah – The British captured this Georgia

coastal town on December 29, 1778.

8 Charleston – On May 12, 1780, British forces

under Clinton forced the surrender of the Charleston militia and Continentals under the command of General Benjamin Lincoln.

The victory was a major setback for American forces in the South.

8A Camden - Fought on August 16, 1780, near Camden, South

Carolina, the Battle of Camden was a disastrous defeat for the Patriots. Gates, the American general, gained a reputation

as a "fool and coward" for his actions and fleeing the battle site. Reports of the results made Banastre Tarleton a national

hero in Britain.

9 Southern Continental Army – Those regular, trained,

and uniformed soldiers of the American army stationed in the South, as distinguished from local militia in each colony.

10 backcountry – South Carolina area west of the

coastal area, especially west of Camden. Today, referred to as the Upcountry or Upstate.

11 Waxhaws – On May 29, a1780, Tarleton’s

Legion overtook and defeated Colonel Abraham Buford and his Third Virginia Continentals as they returned through the Waxhaws

area toward North Carolina after the fall of Charleston. (Known also today as Buford’s massacre) There is some contention

over the origin of the name Waxhaws. It was the name of Native Americans of the region, derived, some historians, believe,

from native language. Others believe it is an English corruption of the original and described not only the Native Americans

of the region but also the waxy-looking haw and "hawfields", (shrubs, either Black Haw ( vibernum prunifolium )or hawthorns

( crataegus linnaeus)prominent in the region. The Waxhaw settlement, just off the Great Wagon Road, today covers parts

of both Carolinas in an area southeast of Charlotte.

12 Pacolet River – An upstate South Carolina river

with its headwaters in North Carolina flowing through present-day Spartanburg and Cherokee Counties before it empties into

the Broad. The armies of Daniel Morgan and Banastre Tarleton crossed the flood-swollen Pacolet as they journeyed toward the

Cowpens.

13 Thicketty Creek – An upstate South Carolina

creek, a tributary of the Broad River. Most likely named for the thick plant growth along its banks. Daniel Morgan and his

army camped along Thicketty before their hurried departure for the Cowpens.

14 Broad River – A river beginning in the mountains

of North Carolina flowing southeast and joining with the Saluda River at present-day Columbia to form the Congaree River.

Morgan, his army, and British prisoners crossed the Broad after the Battle of Cowpens. British General Cornwallis crossed

the Broad in pursuit.

15 "cowpens" – A term, endemic to South Carolina,

referring to open-range stock grazing operations of the colonial period. These were usually cleared areas, 100 to 400 acres

in extent. Many, in eastern South Carolina, were known for their native cane- brakes. Piedmont pastures, though less numerous,

often contained peavine.

16 peavine – A native legume found often

in piedmont South Carolina cowpens.

17 forage – Food for animals or humans. Also, the

search for food for animals or humans.

18 militia – Part-time soldiers, subject to colonial

(state) authority, they sometimes fought with the Continental or standing army in battles such as Camden, Cowpens, and Guilford

Courthouse. Thought unreliable by some Continental officers, they proved themselves at the Battles of Kings Mountain and Cowpens.

19

19 Battle of Kings Mountain – The Overmountain

men and other militia defeated British loyalists at Kings Mountain in upstate South Carolina on October 7, 1780.

20 "Old Waggoner" – Affectionate name given to

General Morgan who began his military career as a wagon driver in the French and Indian War.

21 Saratoga – In fierce battles on September 19

and October 7, 1777, American forces under General Horatio Gates defeated the British under General John Burgoyne. This victory

encouraged France to enter the war to assist the Americans. Saratoga is in upstate New York.

22 "Benny" – Daniel Morgan’s derisive name

for Banastre Tarleton.

23 dragoon – A mounted infantryman, who often rode

his horse into battle and dismounted to fight. Used synonymously with cavalrymen, both of whom could fight on horseback or

dismounted.

24 15 – Dr. Lawrence E. Babits in his book, A

Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens, believes this figure is wrong and has been perpetuated by writers over

the years.

25 John Eager Howard – Native Marylander and Revolutionary

War officer who distinguished himself at the Battle of Cowpens. He was subsequently elected governor of Maryland (1788-91),

and at one time owned much of the land that was to become Baltimore.

26 William Washington – Patriot Lieutenant Colonel

of a cavalry unit, who distinguished himself at Cowpens. He was second cousin, first-removed to George Washington.

27 71st Highlanders – Two battalions

of highland Scottish troops raised by England and sent to America in 1775. 71st Highlanders fought at Charleston,

Camden, and Cowpens, among other battles. At Cowpens, Tarleton initially kept his Highlanders in reserve, but, as the advance

faltered, he ordered them into action against the American right. The Highlanders bore the brunt of the last dramatic events

of the Battle.

28 double envelopment – Envelopment is an attack

on the enemies flank, rear, and sometimes the front. Double envelopment would entail attack or a surrounding on both flanks,

hence all sides.

29 bugler – William Washington’s bugler was

very likely African-American. A famous painting by Ranney dipicts him so. Apparently the bugler didn’t file a pension,

and Washington didn’t leave behind written papers of his own role or of anyone else’s role in the Revolution.

His surname was possibly Ball, Collins, or Collin, but an exact name hasn’t been verified.

30 Island Ford – A normally low-water crossing

point on the Broad River, reached by Island Ford Road. When Morgan, his army, and his prisoners crossed on January 17, the

water was high from heavy rains and flooding.

31 Gilbert Town – Presently, Rutherfordton, North

Carolina. Gilbert Town was a small settlement in 1781 a few miles north of Rutherfordton’s present site.

32 Salisbury – An early town in the North Carolina

piedmont known for its Confederate prison and National Cemetery, today, but lesser known for its Revolutionary War prison,

most likely established in the latter years of the war. There is no evidence the prisoners from the Battle of Cowpens were

imprisoned there.

33 Dan River – A river separating North Carolina

and Virginia.

34 baggage – Military supplies such as tents, tools,

and rations carried in wagons. Burning the baggage (and wagons) allowed an army to travel faster.

35 Catawba River – River originating in the mountains

of North Carolina, flowing eastward, before turning south into South Carolina, where is known as the Wateree, and, further

east, the Santee. Morgan crossed the Catawba west of present-day Charlotte, North Carolina.

36 Battle of Guilford Courthouse – On March 15,

1781, a British army under Cornwallis attacked Nathanael Greene’s patriot forces at Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina

(part of present-day Greensboro). Although Greene’s forces were forced to retire from the field; the British were badly

battered with many men killed or wounded.

37 "Tarleton’s Quarter" - Since it was said that

Tarleton gave no quarter (opportunity to surrender) at the Waxhaws, "Tarleton’s Quarter" came to mean no quarter at

all.

Bibliography

Alden, John Richard. The American Revolution – 1775-1783. New

York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1962.

Babits, Lawrence E. A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens. Chapel

Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

_____, Cowpens Battlefield: A Walking Guide. Johnson City, Tennessee:

The Overmountain Press, 1993.

Baker, Thomas E. Another Such Victory. Eastern National, 1998.

Bearss, Edwin C. Battle of Cowpens: A Documented Narrative. Johnson

City, Tennessee: The Overmountain Press, 1996.

Boatner, Mark M. III. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg,

Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1994.

Buchanan, John. The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution

in the Carolinas. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1997.

Dunbar, Gary S. "Colonial Carolina Cowpens" in Agricultural History.

Berkeley, California: The Agricultural History Society, Vol. 35, 1961.

Fleming, Thomas J. Downright Fighting: The Story of Cowpens – The

Official National Park Handbook. Washington, D. C.: Division of Publications: National Park Service, United States Department

of the Interior, 1988.*

Graham, James. Life of General Daniel Morgan. Bloomingburg, New York:

Zebrowski Historical Services, 1993. Originally published 1856.*

Higginbotham, Don. Daniel Morgan – Revolutionary Rifleman. Chapel

Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979.*

Johnson, Curt. Battles of the American Revolution. New York: Bonanza

Books, 1984.

Lossing, Benson J. The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution. Vol.

2. Freeport, New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1969. First Published 1851.

Morrill, Dan L. Southern Campaigns of the American Revolution. Baltimore,

Maryland: The Nautical and Aviation Publishing Company of America, N. D.*

Moss, Bobby Gilmer. The Patriots at the Cowpens. Revised Edition. Blacksburg,

South Carolina: Scotia Press, 1985.*

Pankake, John S. The Destructive War: The British Campaign in the Carolinas,

1780- 1782. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1985.

Raynor, George. Patriots and Tories in Piedmont Carolina. Salisbury,

North Carolina: The Salisbury Post, 1990.

Roberts, Kenneth. The Battle of Cowpens. New York: Eastern Acorn Press,

1989.*

Roberts, John M. ed. Autobiography of A Revolutionary Soldier by James

P. Collins. North Stratford, New Hampshire: Ayer Company Publishers, Inc., 1989. Originally Published by Feliciana Democrat

Printers, Clinton, Louisiana, 1859

|