|

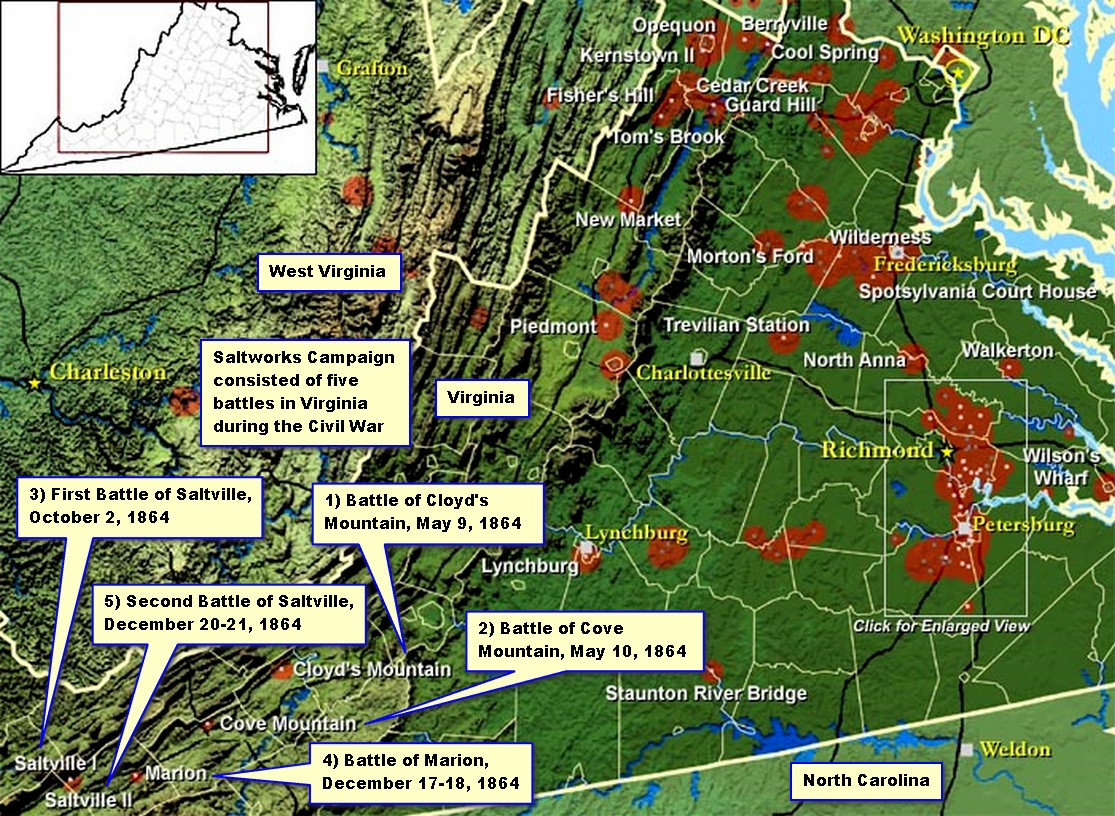

THE CIVIL WAR BATTLE OF SALTVILLE, VIRGINIA, HISTORY

A Research Design

For the Investigation of the Battles of Saltville

On October 2nd, 1864 and December 20th, 1864

A Cooperative Project between

The American Battlefield Protection Program

And Radford University

By

Angela M. Dautartas

C. Clifford Boyd

Rhett B. Herman

Robert C. Whisonant

June 17, 2005

Introduction

History

in Saltville, Virginia, is

as abundant as it is fascinating. From ice-age mammals to prehistoric villages to Civil War battlefields, this small town

seems to have been a cornerstone throughout the ages. This project hopes to preserve that sense of history by continuing to

add to the Saltville story. The focus of this study is narrowed to the two Civil War battles that were fought to gain control

of the Salt-Works, a key resource for the Confederacy. Although these two battles represent only a portion of the significance

of this town, it is a portion deserving of intensive study. In addition, many

of the intricate fortification systems and earthworks are still visible today, and the grounds where the two armies clashed

are still visited frequently by those who wish to remember the past. For these reasons and many others, this project is working

to show how and why Saltville’s invaluable historic resources must be preserved and protected.

| Battle of Saltville History |

|

| Salt, Saltworks, and the Battle of Saltville History |

Overview of Saltville

Sites

Saltville’s salt deposits

have influenced the history of the region since at least the late Pleistocene, when large Ice Age mammals and Paleo-Indians

who hunted them were drawn to the natural salt licks (McDonald, 1984; Roanoke Times, 1996).

In the late 1700s, settlers of European descent began commercial production of salt from brine wells scattered across

the valley floor (Boyd and Whisonant, 2002). By the advent of the Civil War,

Saltville was one of the three largest salt-making centers in the young United States (Sarvis, 1998). During the war, Saltville became one of the prime mineral production centers in the South, and the defensive

fortifications and battles fought there attest to its strategic significance (Rachal, 1953; Marvel, 1992; Whisonant, 1996).

Salt was one of the most crucial

mineral resources to both the military forces of the Confederacy and its civilian population (Lonn, 1933; Holmes, 1993). As the conflict wore on, the salt-producing facilities at Saltville grew into an enormous

network of brine wells, storage tanks, wooden pipes, and open-shed furnaces with large (some up to 1,100 pounds) iron evaporating

kettles (Marvel, 1992). Here, two-thirds of all the salt consumed by the South

during the war was produced (Lonn, 1933).

Because of its national significance

to the Confederacy, Saltville became the principal Union military target in southwestern Virginia (Donnelly, 1959). In response, Confederate engineers had constructed a complex array of trenches, cannon emplacements, sentry

posts, and fortified enclosures between July 1863 and late 1864 (McDonald, 1985), manned at one point by as many as 4,000

troops (Marvel, 1992). Two major battles were fought in October 1864 and December

1864. The October 1864 battle is of particular interest because of the selective

murders by Confederates of a disputed number of African-American Union soldiers lying wounded on the battlefield – the

Saltville Massacre (Davis, 1971, 1993; Marvel, 1991, 1992; Mays, 1998).

At least two dozen sites containing

various components of the battlefields and defensive earthworks system are known in Saltville.

A survey and inventory of all archeological (prehistoric through industrial age) sites in Saltville conducted by McDonald

(1985) identified 21 sites attributable to the 1863-1864 military defenses. Many

of the locations contain multiple features, such as forts with parapets, cannon ramps, and trenches, several sets of trenches,

or (in one case) a “double” fort. Many other Civil War features in

Saltville were not documented by McDonald, including some on the October 1864 battlefield.

These can be seen in the field or on air photos, or are known to local sources (Saltville Historical Foundation, undated;

Kent, 1955; Haynes, oral commun., 2004; Totten, oral commun., 2004). None have

ever been mapped using the precision GPS/GIS technology that will be employed in this project.

Therefore, this research will produce a series of maps that show the location, extent, and condition of one of the

most elaborate Civil War defensive systems built to protect an important industrial location.

This is the first critical step toward the interpretation and preservation of the irreplaceable Civil War resources

at Saltville.

Historical

Background

The First Battle for Saltville- October 2nd, 1864

George D. Mosgrove, a Kentucky

Confederate soldier, described Saltville as a “natural fortress” with hills and ridges in concentric circles,

which greatly aided in the Confederate defenses (Mosgrove, 1957). His account of the battle of Saltville begins in the summer

of 1864, when rumors had it that Union General Stephen Burbridge’s forces were marching towards the Salt-Works on a

parallel course with the Confederate forces under General John Morgan. In late

September, closer to the time of the actual battle, Mosgrove writes that scouts reported a force of six to eight thousand

cavalry with six to ten pieces of artillery were coming from Kentucky,

commanded by General Burbridge, General E.H. Hobson, and Colonel Charles Hanson. In addition, the scouts reported seeing two

possible African- American brigades, which were in fact the 5th and the beginnings of the 6th United

States Colored Cavalry (USCC). General Basil Duke, a member of Morgan’s army, also presents an account of the battle

of Saltville in his book (Duke, 1960). He notes that in addition to the threat presented by General Burbridge, two other Union

generals, General Jacob Ammen and General A. C. Gillem, were also advancing towards Saltville, but were coming from Knoxville, Tennessee, as opposed to the Kentucky route Burbridge was taking.

In response to the scout’s

information, Colonel Henry Giltner of the Confederacy sent Colonel Edward Trimble with 150 men to Richlands, 40 miles from

Saltville, to head off the Union forces. Colonel Trimble then ordered Colonel Giltner to take 100 of his men to the gap in

Paint Lick Mountain to protect the main turnpike road running through that gap, and to provide

reinforcements should Trimble need to fall back (Duke, 1960). General Burbridge

sent a battalion to Jeffersonville, on the Confederate right,

to try another approach towards the Salt-Works. Colonel Giltner then sent Captain Bart Jenkins with another company to meet

the Union forces at Jeffersonville. Colonel Trimble did skirmish

with Federal forces at Cedar Bluff and was forced to fall back. The main Confederate force of 300 men was then pushed back

to the summit of Clinch Mountain, and attempted to hold that mountain pass into the valley. The Union army sent 500 men around

Paint Lick Mountain

toward Jeffersonville, flanking the gap (Duke, 1960).

On the evening of September 30th,

Captain Edward Guerrant made his headquarters at the home of George Gillespie, near the grounds of General Bowen (Davis, 1999). Late at night,

the captain was awakened with news that the Union forces were firing on General Bowen’s property. Captain Guerrant responded

by sending a member of the 10th Kentucky cavalry to warn Colonel Giltner, and

by sending the 4th Kentucky cavalry to picket towards the Union (Davis, 1999). That same day, Colonel Robert Preston also arrived in Saltville with his reserves.

He was unaware of the strength of the Union forces approaching the town; his orders had simply been to reach Saltville as

quickly as possible, according to the account of one of his reservists and friends, John Wise (Wise, 1899).

On October 1st, the

evening before the battle, the Federal soldiers camped on the grounds of General Bowen, two miles outside of the Confederate

position within Saltville. At that time, only the Virginia

reserves were actually stationed within the town, with but a few pieces of artillery. The troops were led by General Alfred

“Mudwall” Jackson, a man very much disliked and who did not inspire much confidence. However, General John Williams

of the Confederacy was unexpectedly at Castle Woods, not far from Saltville (Wise, 1899).

The 64th Virginia Battalion,

under Lieutenant Colonel Robert Smith with 250 men, and the 10th Kentucky cavalry

were both on the summit of Flat Top

Mountain, guarding possible entrances to Saltville (Wise, 1899). Following a skirmish with Federal troops, the regiments were forced to fall back to

Laurel Gap. In addition, the 4th and 10th Kentucky Mounted Rifles were already posted at Laurel Gap.

Laurel Gap is surrounded on either side by tall cliffs, thought to be inaccessible, and not to be scaled. However, the Mounted

Rifles were posted as far up the left cliff as possible, and the 64th battalion was stationed on the right (Mosgrove,

1957). Colonel Trimble was also sent up behind the mountain with his battalion. Late in the afternoon, Union forces secured

passage through the mountain by pushing the 64th Battalion from its position and crossing on the right. The remaining

Confederate forces then retreated to Saltville. At Broadford the road into the town forked and split into two separate roads,

both leading southward into the valley toward Saltville. Colonel Giltner took the 64th Virginia and the 10th

Kentucky Mounted Rifles across the Holston River,

and ordered Colonel Trimble to take the 10th Kentucky cavalry and the 4th

Kentucky cavalry down the main river road, thus covering

both avenues of approach. By midnight, the entire Federal force was able to cross

the mountain through Laurel Gap (Mosgrove, 1957).

| In defense of Salt |

|

| Confederates held the Saltworks until sheer numbers overwhelmed their position |

The battle commenced on October 2nd with the

Union troops attacking pickets and skirmish lines. The 4th and 10th Kentucky

cavalry under Colonel Trimble then crossed over to ground occupied by Giltner to act as reinforcements. Colonel Trimble’s

men then attacked the Union forces, and fell back slowly. Meanwhile, the Union forces charged the 4th Kentucky cavalry and skirmished with them for half an hour. Part of

the 4th occupied a position high on the hill near “Governor” Sanders’ house, and there General

Felix Roberston’s brigade of 250 men arrived in advance of General Williams to reinforce the Confederate units (Davis,

1999).

At this point, Mosgrove’s

account lists fighting and changing of positions, with a bit of confusion as to which regiment was moving where. Ultimately,

the Confederate forces ended up positioned all along the ridges. General Williams was on the high ridge near Sanders’

hill, and Giltner was pushed back to the bluffs along the Holston

River (Mosgrove, 1957). The 10th KY cavalry was on the bluff

at the ford, with the 10th KY mounted rifles to their left. The 64th VA reserves were then to the left

of that regiment, and the 4th KY was to the left of them. Finally, on the extreme end of the line were Colonel

Preston’s reserves. Another battalion of reserves under Lieutenant Colonel Smith and Major John S. Prather were barricaded

around Governor Sanders’ home (Wise, 1899). The Federal forces advanced

on the Confederate line. At midmorning, the Union forces formed into three columns and attacked the reserves surrounding Governor

Sanders’ house. The 13th Battalion of Virginia Reserves stationed at the house fought, but the Union forces

were able to push them back to Chestnut Ridge. The Union troops stormed the yard, and followed the reserves up Chestnut Ridge,

where they were met by the Confederate brigades of General Robertson and Colonel George Dibrell.

The three Federal columns then

moved to attack Trimble’s position at the ford. One column went directly down Sanders’ hill, another moved along

the river, and one swept across the wide bottom of the hill. The Federal forces crossed the ford, scaled the opposite cliff

and attacked Trimble’s position. In response, the 10th Kentucky mounted

rifles and the 64th Virginia was sent to support

Trimble. Colonel Giltner went to the reserves barricaded in trenches at the nearby church and moved them down the road and

up by Elizabeth Cemetery

to support Trimble. Trimble fell back, and the colonel himself was killed (Mosgrove, 1957).

The Federal forces were then repulsed

on all sides, particularly on the Confederate left. The Federal column led by Colonel Hanson was on the far left side of the

mountain. His brigade eventually met up with the 4th Kentucky and Preston’s

reserves. Active firing ceased around 5 in the evening, and at that point the Confederates were able to hold the mountain

pass at Hayter’s Gap, which was the most direct route out of Saltville (Mosgrove, 1957).

The Union troops continued

to hold their position one mile out of Saltville until nightfall. Generals John Breckinridge and John Echols arrived after

nightfall, with the small brigades of Generals Basil Duke, George Cosby and John C. Vaughn. According to the memoirs of General

Duke, General Vaughn was left at Carter’s Station, while General Cosby and he were ordered by General Echols to head

on to Bristol on September 30th (Duke, 1960). However, the following day, they received word from General Echols that they were

to head to Saltville, and arrived shortly after their own brigades. With the “fresh” brigades, the Confederates

were reinforced, and intended upon resuming the offensive in the morning (Mosgrove, 1957).

Mosgrove noted that he saw at

least four hundred members of the USCC in the battle during the day. That evening, General Dibrell told Mosgrove that his

men had fought 2500 Yankees during the battle, and had taken down 200 of those men. After dark, Captain Guerrant and Mosgrove

also met up with General Robertson, who claimed that his men had, “killed nearly all the negroes.” At the close

of the evening, the 4th Kentucky relieved Trimble’s

battalion of guarding the ford between the Confederate and Federal camps (Mosgrove, 1957).

Monday, October 3rd

began with a Federal retreat ordered by Burbridge early in the morning, still during the dark. The Union troops abandoned

their position without taking much of their equipment, and even leaving some of the wounded behind on the field in order to

gain ground on the expected Confederate pursuit. General Breckinridge then ordered a scout to locate the Union forces (Duke,

1960). Captain R.O. Gaithright was sent to pursue the Federals from the rear,

while General Williams was sent with the brigades of Duke, Cosby and Vaughn down through Hayter’s Gap to intercept the

Union at Richlands. Colonel Giltner’s brigade was also sent in pursuit of the Union

troops, but was instructed not to follow too close to allow General Williams enough time to advance beyond the Union movements.

Evidence of the Federal retreat

was seen all along the route towards Laurel Gap. Captain Gaithright eventually caught up with some of the African-American

regiments near Laurel Gap. Late in the afternoon, Captain Gaithright also spotted the rear of the Federal column crossing

Clinch Mountain.

By dusk, Colonel George Diamond with the 10th Kentucky cavalry attacked the Federal

rear while crossing the Clinch River. General Duke wrote that he and General Cosby did overtake

General Burbridge at Hayter’s Gap; however, mistakes in reconnaissance and other tactical errors allowed the Union to escape. Thus, by noon the following day, it became obvious that General Williams had been unable

to head off the Union retreat, due to their head start. The pursuit was ended and the first battle for Saltville was over

(Mosgrove, 1957).

On October 3rd, Mosgrove

wrote that Colonel Hanson of the Federal army was lying wounded in a field hospital, having been shot by a minie ball; he

was drunk and swearing at the hospital staff. This same hospital is where Mosgrove writes that while surgeon William H. Gardner

was tending the Federal wounded, three armed Confederate soldiers stormed into the hospital and fatally wounded five African-American

soldiers. He also claims to have witnessed a great deal of slaughtering of members of the USCC on the fields, primarily by

two Tennessee brigades under the command of General Robertson

and Colonel Dibrell. However, Mosgrove never specifies the total number of black soldiers killed during the massacre. General

Burbridge submitted his casualty report stating that of the members of the 5th USCC, 22 men were killed, 37 wounded

and 53 were missing. Captain Guerrant also discussed the incident in his diary. He noted that he heard the continuous

sound of rifle fire which meant the death of, “many a poor negro who was unfortunate enough not to be killed yesterday.”

He also wrote that his men did not take any Negro prisoners, and that great numbers of the African-American soldiers were

killed. However, he did not specify any numbers of soldiers killed (Mosgrove, 1957).

The Second Battle for Saltville- December 20th, 1864

General George Stoneman led forces

comprised of General A.C. Gillem’s men, General Stephen Burbridge’s Kentucky

battalions, and the 5th and 6th United States Colored Cavalry and the 10th Michigan on a raid on Saltville on December 20th, 1864. The Union forces had

6-7,000 men in total. Their objective was the same as General Burbridge’s had been in October of that year; they intended

to destroy the Salt-Works.

The Confederate army pursued General

Stoneman’s army from Marion. Confederate General John

Breckinridge ordered one column to take the road to the left in to Rye

Valley, but this route proved problematic, as the company lost their

way several times during the nighttime passage. In the morning, the company continued down the mountain into Rye Valley, and turned up the valley, and marched throughout

the day, ending at Mount Airy,

on the Wytheville and Marion road (Wise, 1899).

Two roads led into Saltville;

the Glade Spring road lay to the southwest, and the Lyon’s Gap road led from the southeast.

Three hills a mile out of Saltville barricaded the convergence of these two roads. On these hills, protecting these roads

the Confederates had constructed two forts, Fort Breckenridge

to protect Glade Spring and Fort Statham

to guard Lyon’s Gap. Colonel Robert Preston was stationed in Saltville with 500 men,

charged with protecting these two fortifications. With him was Captain John Barr, who commanded the artillery (Wise, 1899). With these limited resources, Colonel Preston picketed both roads to try and meet

the approaching Union troops.

General Basil Duke with a detachment,

who had traveled from Abingdon along the Saltville road, and Captain Tom Barrett with men from the 4th Kentucky mounted rifles were also en route to Saltville to head off

the coming raid. By the time General Breckinridge’s forces reached Preston mansion

at Seven Mile Ford on the outskirts of Saltville on the evening of the 20th of December, General Duke and Captain

Calvin Morgan were already there, watching Saltville burn (Duke, 1960).

General Gillem reached Saltville

first, attacking Colonel Preston’s pickets on the Glade Spring road. Shortly after, General Burbridge’s men attacked

at the Lyon’s Gap road. The Union forces crested both Fort

Statham and Fort Breckenridge, and moved down into the town and descended upon the Salt-Works. Colonel

Preston called the surviving members of his reserves into retreat, and evacuated the town (Wise, 1899). The Federal soldiers destroyed 1000 of 3000 boiling kettles and burned a number of the evaporating sheds

before moving on to rip up sections of the nearby Virginia and Tennessee railroad. However, they failed to damage any of the actual salt wells, and the

remaining kettles and sheds were sufficient to continue the needed salt production until the end of the war.

After the raid, General Stoneman

and General Gillem fell back to Tennessee, while General Stephen Burbridge retreated through

Pound Gap and into Kentucky.

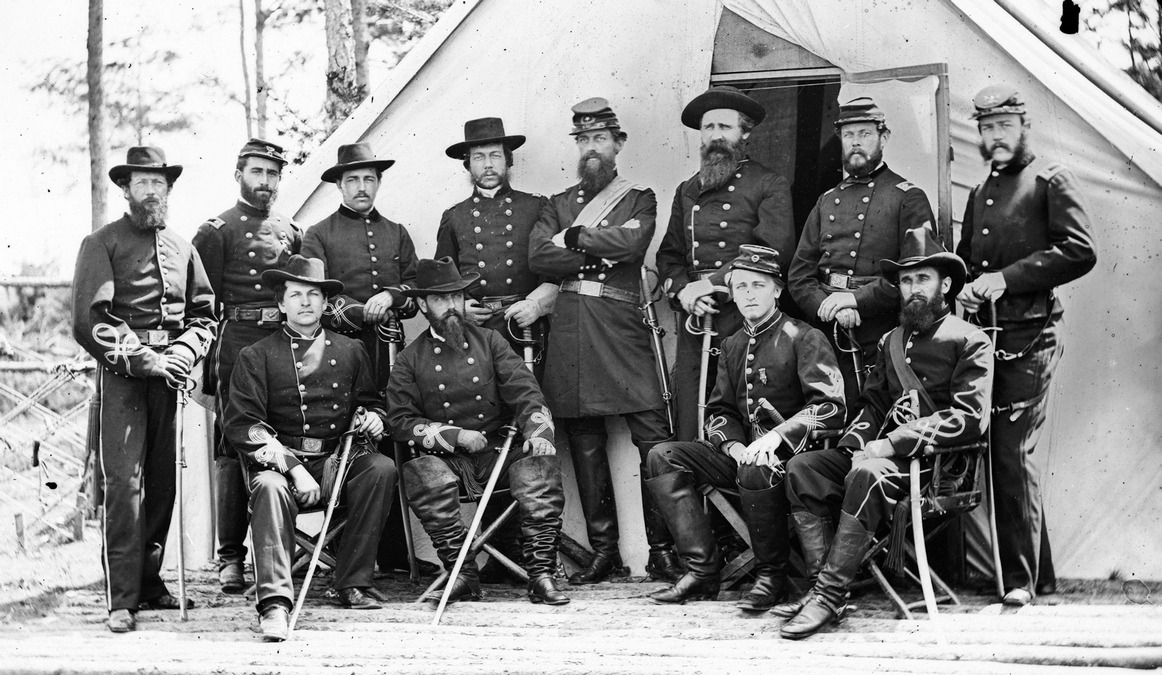

| Stoneman's Raid |

|

| Gen. George Stoneman and staff in 1863 |

Research Goals

The battles for Saltville

are not the most prominently known within Civil War history, but they are significant historical events which should not be

ignored. Therefore, one of the primary goals of this research is to expand and affirm the knowledge base about this town and

this site in order to ultimately increase awareness of the importance of this site. In order to accomplish this task, the

research will concentrate on determining the boundaries of the battle, and will search for confirmation of the historical

record in regards to areas of encampment, artillery positions, barricades, and other military movements.

A second, but equally important,

goal is to examine as many of the defining features of both battlefields according to KOCOA standards and the effect of the

action at these features on the ultimate outcome of the battles. The defining features from both battles have been categorized

into critical, major and minor defining features, in decreasing order of priority. The critical defining features will be

mapped, using GPS and GIS technology, surveyed using the geophysical equipment, and archaeologically tested during the first

summer’s fieldwork, while the major and minor defining features will be analyzed during a later stage of the project.

There are several questions

that can lead the direction of this project. Those questions include: Did both battles for Saltville occur at the locations

described within the historical record? Is the record correct in its placement of the encampments, picket lines, artillery

positions barricades and other military movements? What is the geophysical signature of these various military features? Where is the boundary extent of both battles? What (if any) artifacts remain on the

surface, or close subsurface to confirm the historical information? Have both battle sites been completely examined by the

local collectors? Through the historic research, mapping, archaeological survey and geophysical survey, it is anticipated

that many or all of these questions will be addressed and answered. The Saltville sites present a challenge in that there

is a vast amount of ground to be examined, and time is limited. However, through prioritizing areas to be researched and through

multiple methods of analysis, it is expected that the majority of these questions will be addressed by the completion of the

project.

Defining Features and KOCOA Analysis

A defining feature may

be any feature mentioned in battle accounts that can be located in the ground, including both natural terrain features and

man-made structures. The KOCOA system has been developed by military experts to analyze defining features, focusing primarily

on terrain but also with consideration for historic structures that were significant to the battles. Key terrain, obstacles,

cover and concealment, observation points and avenues of approach and retreat are the five categories into which a defining

feature can be placed. One of these five criteria must be met in order for a feature to be classified as a “defining

feature”; the relative importance of that defining feature depends then upon its significance to the ultimate success

or failure of the regiments in battle.

The critical defining features

for the October 2nd, 1864 battle and the December 20th, 1864 battle at Saltville are shown in Tables

1 and 2.

Major and minor defining

features will be delineated in the same fashion and surveyed and analyzed during the later stages of the project. In addition,

we must stress that many additional elements of the Saltville defensive complex, including fortifications, gun emplacements,

trenches, and sentry posts are not included in the list of defining features because they are not mentioned in the historic

record of either battle. However, many of these earthworks are still in excellent condition, and should be considered within

the context of any preservation planning. Therefore, as many of these features as possible will be mapped, first because they

must be inventoried and evaluated and second, because they afford a rather unique opportunity to analyze a potentially “nationally

significant site for the study of Civil War era military engineering” (Lowe, 2004).

Data

Needs

Historic records will be thoroughly

examined in order to gain an understanding of the events of both battles. Examination of these records will also help determine

the defining features of the battles and will aid in prioritizing features to be surveyed.

Local historians and collectors

will be consulted in order to garner a better understanding of the integrity of these sites, and to eliminate the need for

some “presence and absence” testing to delineate the boundary of the battles. Consultation with these collectors

will also help ensure that the project does not rely solely on historic information of unknown accuracy.

One of the main focal points of

this project will be to amass as thorough a spatial data set as possible. Detailed maps of the boundaries of the battles,

locations of earthworks, and locations of artifacts will be developed in order to convert this information into a GIS that

can then be used to analyze troop movements and positions.

In addition to other methods, a

metal detector survey will be used to help locate any artifacts pertaining to the battles. The types and frequencies of artifacts

found could help describe the characteristics of the location and determine whether they pertain to an encampment or an area

of conflict.

A description of the state of preservation

of the earthworks and battlefield features will also be developed, in connection with a detailed description of the surrounding

environment and vegetation. This survey will be useful in the development of a preservation plan to further protect the battlefields

from natural erosion or artificial destruction.

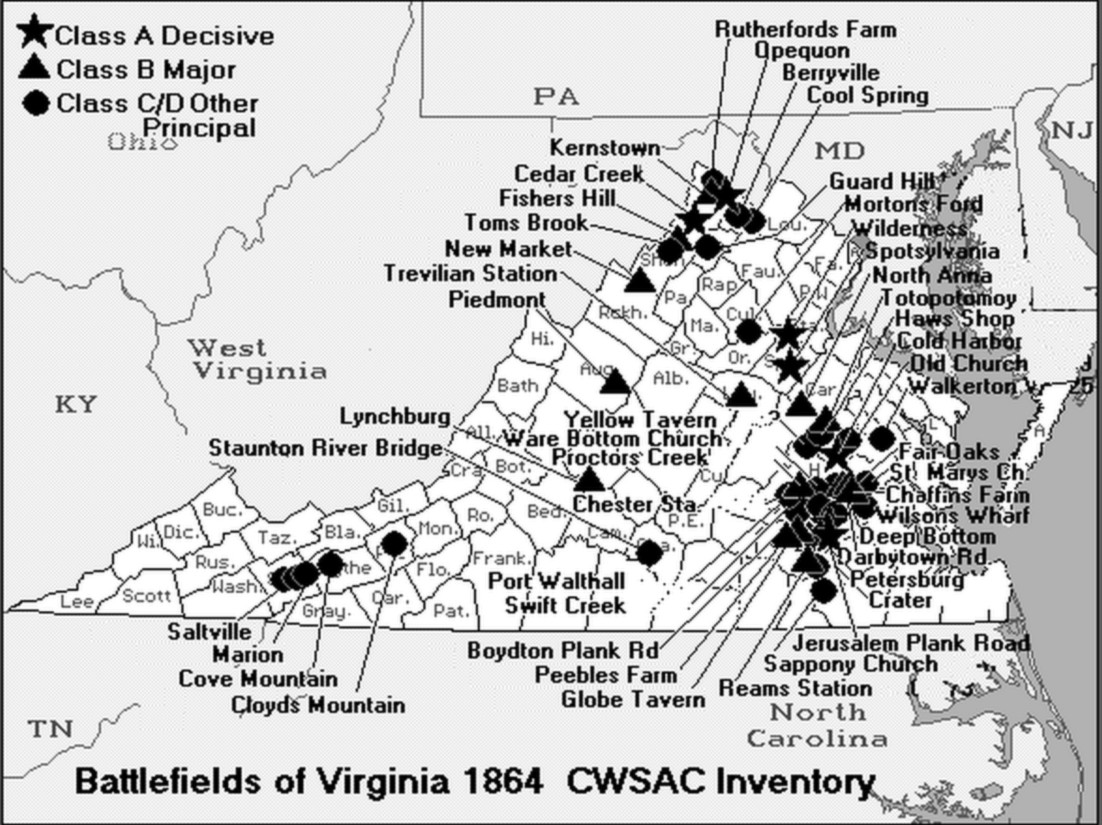

| Map of Major Civil War Battles in Virginia in 1864 |

|

| Map of Principal Virginia Civil War Battles in 1864 |

Methodology

Before the fieldwork begins, all historic

records, including publications, diaries, websites, and previous research files will be examined in order to collect the most

comprehensive background possible.

The location of several of the earthworks

will be mapped and surveyed prior to the two-week field schools in order to complete the work in “leaf-off’ conditions.

In addition, areas of the battle will be scouted and briefly surveyed to ensure that they will be accessible for future work.

Members of the Radford

University team, along with students from the archaeology field school

and a field director will comprise the personnel conducting the majority of the fieldwork. Local historians and collectors

may also accompany project members to various sites as guides or interested observers.

The majority of the work done in Saltville

will focus on GPS and GIS mapping and completing a geophysical survey. In addition to using the GPS equipment to create a

spatial data set noting the locations of the battle and any surface find artifacts, metal detecting will also be used to locate

any artifacts. To facilitate the metal detector survey, a grid will be laid out in the area to be scanned prior to any detecting.

The size of the grid will be directly proportional to the size of the area being investigated. A small, 50 meter square area

may require only a 5 square meter grid, while a larger, open area may require a 15 meter grid or larger. Any “hit”

registered by the metal detector will be flagged, mapped onto the master grid and field map, and entered into the GPS data

logger. Once mapping is completed, the artifact can then be excavated, the depth can be recorded, and the artifact can be

transferred into an individual bag with a code for its grid location and object designation.

Concerning the geophysics aspect of the

project, preliminary electrical resistivity scans on Breckenridge and South Walnut forts have revealed features distinct from

the natural background. Further geophysical work at Saltville for this summer includes carrying out the following scans:

(1)

A surface resistivity scan of the entire Breckenridge area. The known gravesites there will provide a basis from which we

should be able to identify any other gravesites. In addition to the surface scan, we will repeat the scan at greater depths

in order to try to discern any other features associated with the area.

(2) Resistivity scans of the "roads" connecting

the two ends of both the Hatton and Walnut fort systems. The goal of this is to try to illuminate some of the engineering

choices made by the designers of these fort systems regarding available construction materials and field engineering practices.

(3)

A focused resistivity scan of the south Walnut fort. A preliminary scan had revealed a feature of possible interest in this

area. We plan to more precisely delineate this subsurface anomaly to try to discern if it is from human activity, a natural

feature, or an instrumental anomaly (poor ground contact with the electrodes) from the previous scan.

(4) Magnetic

scans of the Hatton and Walnut fortification systems, and the Breckenridge and Statham forts. With Breckenridge, the magnetic

data will be examined with the surface resistivity data to see if there are any correlations.

In addition, field notes, field maps,

daily logs, and record forms will all be used to keep a careful, detailed record of all fieldwork and analysis. Black and

white, color slide, and digital photographs will be taken where appropriate to augment this record. Ultimately, a detailed

GIS will be developed showing the locations of the battlefields and locations of any artifact finds and defining features.

Another map will be created showing the potential National Register boundary as well as core and study areas. When fieldwork

is completed, all geophysical and spatial data will be analyzed, any collected artifacts will be studied, and the final report

and GIS will be created.

Laboratory

Activities

Although archeological excavations and

retrieval of artifacts are not major activities in this project, we do expect to find some new materials. Most of these are anticipated to be surface or near-surface small metallic objects, such as shell fragments,

bullets, belt buckles, and the like. Recovered artifacts will be cleaned, identified,

and catalogued, and the location of each item plotted on the base maps. This

work will be performed primarily in the archeology laboratory at Radford

University, but some preliminary work can be accomplished at the Field

Research Station in Saltville. The ultimate aim is to archive the artifacts according

to National Park Service standards in the Museum of the Middle Appalachians. This

project partner has agreed to curate the project archeological materials for study and public education.

Curation

All materials from this project will

be analyzed at the Radford University Physical Anthropology and Archaeology laboratory. Upon completion of analysis, all artifacts

will be returned to Saltville to be curated at the Museum of the Middle Appalachians. The project team members, the museum

staff, and the Town of Saltville have agreed upon this arrangement.

Report

A final report will be generated upon

completion of all fieldwork, artifact analysis and geophysical analysis. The report will describe the project, site, historical

significance, site integrity, and will address the research goals, questions and answers to those questions. In addition,

the final report will also include a proposal for a nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. The sections of the report will include (but are not limited to):

1)

Title Page

2)

Table of Contents

3)

Introduction- site description and historical background, including a KOCOA description

4)

Materials and Methods- a description of the various geophysical, geographic, and archaeological tools

and methodology used in data collection, photography and mapping techniques, and artifact collection methods

5)

Analysis- description of the analytic techniques employed in the archaeology laboratory and the computer

and technology assisted techniques used to process the GPS and geophysical data

6)

Assessment- will combine the data gathered in the field and in the laboratory to address the research

questions and goals, and will consider future research. Suggestions for land to be nominated to the National Register will

be formulated from this assessment

7)

Conclusion

8)

References

Deliverables

Upon completion of the project, three

copies of the draft report will be sent to the NPS American Battlefield Protection Program for corrections and suggestions.

Following any necessary corrections, three copies of the final report will be submitted, along with a copy on a compact disc.

Any GIS maps created for the project will be submitted as ArcView shapefiles, and will include appropriate metadata. Any photographs,

digital, black and white, or color slides, will also be submitted in an appropriate format.

Treatment

of Human Remains

Should any human remains be unexpectedly

encountered during any phase of the project, state and federal policy will dictate their handling. If human remains are encountered, all work will cease, and the State Historic Preservation Officer and

local law enforcement will be immediately notified. All remains would be treated in a professional and respectful manner. No remains will be disinterred or moved without the appropriate permits. No photographs of human remains will be displayed or published.

NAGRA

and ARPA Procedures

The Archaeological Resources Protection

Act (ARPA) (1979) and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) (1990) are both federal laws that

seek to protect archaeological resources and Native American burial sites on public or tribal land from disturbance or destruction.

The focus of our project is on mapping and remote sensing; the limited test excavations that may occur will be conducted on

Civil War fortifications and will not impact any graves, Native American or otherwise. Furthermore, all sites to be investigated

are either privately owned or owned by the Town of Saltville

and are not located on any federal (public) or Native American tribal lands.

Conclusions

This research design will act as a basis

for the thorough investigation of the two Saltville Civil War battlefield sites. The goal of this project is to map and record

the areas of both battles, and to amass as much information as possible to confirm and augment the historic record pertaining

to these two events, through archaeological and geophysical survey investigations. Support for this project comes from the

National Parks Service, Radford University,

the town of Saltville, and the Museum of the Middle Appalachians

(Saltville Foundation), as well as many individuals within the town.

(References and related reading are listed at bottom of page.)

Recommended

Reading: Saltville Massacre (Civil War Campaigns

and Commanders). Description: In October 1864, in the mountains of southwest Virginia,

one of the most brutal acts of the Civil War occurs. Brig. Gen. Stephen Burbridge launches a raid to capture Saltville. Included

among his forces is the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry. Repeated Federal attacks are repulsed by Confederate forces under the command

of Gen. John S. Williams. Continued below…

As the sun

begins to set, Burbridge pulls his troops from the field, leaving many wounded. In the morning, Confederate troops, including

a company of ruffians under the command of Captain Champ Ferguson, advance over the battleground seeking out and killing the

wounded black soldiers. What starts as a small but intense mountain battle degenerates into a no-quarter, racial massacre.

A detailed account from eyewitness reports of the most blatant battlefield atrocity of the war.

Recommended

Reading: Saltville

(VA) (Images of America), by Jeffrey C. Weaver (Author), The Museum of the Middle Appalachians (Author): Description:

Saltville, Virginia, lies on the banks of the North Fork of the Holston River on the border between Smyth and Washington Counties.

Its history began very long ago; in fact, archeological evidence suggests extensive human habitation there for more than 14,000

years. Saltville was named because it was a source of salt,-and by the end of the 18th century, a thriving industry was born.

During the Civil War, Saltville attained considerable importance to the Confederate government as a supply of salt. Continued

below…

A large Confederate

army garrison was maintained there, and extensive fortifications were constructed. After the Civil War, the town led the way

in industrialization of the South. Flip through the pages of Images of America: Saltville to learn why Saltville is one of

the most historic places in the world. About the Author: The Museum of the Middle Appalachians, located on Palmer Avenue

in Saltville, was established by the Saltville Foundation in the 1990s. It has become the repository for fossils, artifacts,

and photographs of the region. Author Jeffrey C. Weaver holds degrees in American history from Appalachian State University,

and after serving in the U.S. Army for several years, he worked as a contracting officer for the U.S. Department of Energy.

He is currently the manager of the Chilhowie Public Library.

Recommended

Reading: Lee's Endangered Left: The Civil War In Western Virginia, Spring Of 1864. From Kirkus Reviews: A competent, well-executed addition to the

ever-growing horde of Civil War literature, by Duncan (History/Georgetown University). The author reconsiders Union General

Ulysses S. Grants attempts to destroy the Confederates, led by General Robert E. Lee, at their traditional stronghold in western

Virginia and his efforts to threaten Lynchburg

during the spring and summer of 1864. Continued below…

The writing

here is crisp; refreshingly, our chronicler pays sharp attention to the effects of the campaign on civilians as the Union

army penetrated beyond its supply lines and came to live off the countryside in one of the Confederacy’s richest agricultural

regions, bringing home the harsh realities of war to civilians. The campaign swung back and forth, with Northern victories

at Cloyd's Mountain and New

River Bridge and Confederate routs at New Market, followed by a Union

failure to seize Lynchburg. Though the campaign proved costly

to the South, overall the Unions hope to capture the Shenandoah Valley foundered and the Confederates then went on to threaten

Washington, D.C. Duncan sensitively employs a wide variety of sources, military and civilian, to add to the coherence of his

account. Still, the books scope remains narrow, focusing on a not terribly glamorous period in the wars history; then, too,

wed do well to have the volume trimmed by a third. Duncan’s contention that the Unions

severity in dealing with civilian populations was directly reciprocated when the Confederates took Chambersburg,

Penn., creating a chain of vengeance that culminated when Sherman marched through the South, is insightfully argued, offering a fresh analysis to the

historical debate. Casual readers of the Civil War genre (and many die-hard buffs, as well) may want to leave this superbly

researched yet ultimately too specialized study for the historians to ponder. Includes 20 photographs.

Recommended

Reading: The Official Virginia

Civil War Battlefield Guide. Review: This

is one of the most useful guides I've ever read. Virginia

was host to nearly one-third of all Civil War engagements, and this guide covers them all like a mini-history of the war.

Unlike travel books that are organized geographically, this guide organizes them chronologically. Each campaign is prefaced

by a detailed overview, followed by concise (from 1 to 4 pages, depending on the battle's importance) but engrossing descriptions

of the individual engagements. Continued below…

These descriptions

make this a great book to browse through when you're not in the car. Most sites' summaries touch on their condition--whether

they're threatened by development (as too many are) and whether they're in private hands or protected by the park service.

But the maps are where this book really stands out. Each battle features a very clear map designating army positions and historical

roads, as well as historical markers (the author also wrote “A Guidebook to Virginia's Historical Markers”), parking, and visitors'

centers. Best of all, though, many battles are illustrated with paintings or photographs of the sites, and the point-of-view

of these pictures is marked on each map!

Recommended

Reading: The

Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864 (McFarland & Company). Description: A

significant part of the Civil War was fought in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, especially in 1864. Books and articles

have been written about the fighting that took place there, but they generally cover only a small period of time and focus

on a particular battle or campaign. Continued below...

This work covers

the entire year of 1864 so that readers can clearly see how one event led to another in the Shenandoah Valley and turned once-peaceful

garden spots into gory battlefields. It tells the stories of the great leaders, ordinary men, innocent civilians, and armies

large and small taking part in battles at New Market, Chambersburg, Winchester, Fisher’s

Hill and Cedar Creek, but it primarily tells the stories of the soldiers, Union and Confederate,

who were willing to risk their lives for their beliefs. The author has made extensive use of memoirs, letters and reports

written by the soldiers of both sides who fought in the Shenandoah Valley in 1864.

Recommended

Reading: Shenandoah Summer: The 1864 Valley Campaign. Description: Jubal A. Early’s disastrous battles in the Shenandoah Valley

ultimately resulted in his ignominious dismissal. But Early’s lesser-known summer campaign of 1864, between his raid

on Washington and Phil Sheridan’s renowned fall campaign, had a significant impact on the political and military landscape

of the time. By focusing on military tactics and battle history in uncovering the facts and events of these little-understood

battles, Scott C. Patchan offers a new perspective on Early’s contributions to the Confederate war effort—and

to Union battle plans and politicking. Patchan details the previously unexplored battles at Rutherford’s Farm and Kernstown

(a pinnacle of Confederate operations in the Shenandoah Valley) and examines the campaign’s

influence on President Lincoln’s reelection efforts. Continued below…

He also provides

insights into the personalities, careers, and roles in Shenandoah of Confederate General John C. Breckinridge, Union general

George Crook, and Union colonel James A. Mulligan, with his “fighting Irish” brigade from Chicago.

Finally, Patchan reconsiders the ever-colorful and controversial Early himself, whose importance in the Confederate military

pantheon this book at last makes clear. About the Author: Scott C. Patchan, a Civil War battlefield guide and historian, is

the author of Forgotten Fury: The Battle of Piedmont, Virginia, and a consultant and contributing writer for Shenandoah, 1862.

Review

"The author's

descriptions of the battles are very detailed, full or regimental level actions, and individual incidents. He bases the accounts

on commendable research in manuscript collections, newspapers, published memoirs and regimental histories, and secondary works.

The words of the participants, quoted often by the author, give the narrative an immediacy. . . . A very creditable account

of a neglected period."-Jeffry D. Wert, Civil War News (Jeffry D. Wert Civil War News 20070914)

"[Shenandoah

Summer] contains excellent diagrams and maps of every battle and is recommended reading for those who have a passion for books

on the Civil War."-Waterline (Waterline 20070831)

"The narrative

is interesting and readable, with chapters of a digestible length covering many of the battles of the campaign."-Curled Up

With a Good Book (Curled Up With a Good Book 20060815)

"Shenandoah

Summer provides readers with detailed combat action, colorful character portrayals, and sound strategic analysis. Patchan''s

book succeeds in reminding readers that there is still plenty to write about when it comes to the American Civil War."-John

Deppen, Blue & Grey Magazine (John Deppen Blue & Grey Magazine 20060508)

"Scott C. Patchan

has solidified his position as the leading authority of the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign with his outstanding campaign

study, Shenandoah Summer. Mr. Patchan not only unearths this vital portion of the campaign, he has brought it back to life

with a crisp and suspenseful narrative. His impeccable scholarship, confident analyses, spellbinding battle scenes, and wonderful

character portraits will captivate even the most demanding readers. Shenandoah Summer is a must read for the Civil War aficionado

as well as for students and scholars of American military history."-Gary Ecelbarger, author of "We Are in for It!": The First

Battle of Kernstown, March 23, 1862 (Gary Ecelbarger 20060903)

"Scott Patchan

has given us a definitive account of the 1864 Valley Campaign. In clear prose and vivid detail, he weaves a spellbinding narrative

that bristles with detail but never loses sight of the big picture. This is a campaign narrative of the first order."-Gordon

C. Rhea, author of The Battle of the Wilderness: May 5-6, 1864 (Gordon C. Rhea )

"[Scott Patchan]

is a `boots-on-the-ground' historian, who works not just in archives but also in the sun and the rain and tall grass. Patchan's

mastery of the topography and the battlefields of the Valley is what sets him apart and, together with his deep research,

gives his analysis of the campaign an unimpeachable authority."-William J. Miller, author of Mapping for Stonewall and Great

Maps of the Civil War (William J. Miller)

Try the Search Engine for Related Studies: Battles of Saltville Virginia during the American

Civil War History, Detailed Battlefields of Virginia, Confederate Union Army at Saltville, Battle of the Salt works Saltworks,

Facts, Summary of Events

References

Boyd, C. C., Jr., and Whisonant, R. C., 2002, Prehistoric and historic archaeology in Saltville, Virginia: 32nd Annual Meeting of the Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference, Abstracts, p. 22.

Davis, W. C., 1971, The Massacre at Saltville: Civil War Times Illustrated,

v. 9, pp. 4-11, 43-48.

Davis, W. C., 1993, Saltville Massacre, in Current, R. N., editor, Encyclopedia

of the Confederacy: Simon and Schuster, New York, pp. 1363-1364.

Davis, William C. and Meredith

L. Swentor, eds. Bluegrass

Confederate: The Diary of Edward O. Guerrant. Louisiana State University Press: 1999.

Donnelly, R. W., 1959, The Confederate lead mines of Wythe County,

Va.: Civil War History, pp. 402-414.

Duke, Basil W. A History of Morgan’s

Cavalry. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN: 1960.

Guide to Sustainable Earthworks

Management, 1998, Chapter 7. Technical Support

Topics &

GPS Mapping Methodology for Earthworks Management and

Evaluation: National Park Service Journal, pp. 97-112.

Holmes, M. E., 1993, Salt, in Current, R. N., editor, Encyclopedia of the

Confederacy: Simon and Schuster, New York,

pp. 1362-1363.

Kent, W. B., 1955, A History of Saltville, Virginia: Commonwealth Press, Radford, p. 156.

Lonn, E., 1933, Salt as a Factor in the Confederacy: Walter Neale, New York, p. 322.

Lowe, D. W. 2004, Saltville Fortifications Site Report: unpublished National Park Service preliminary analysis of selected

Saltville Civil War fortifications, p. 5.

Marvel, W., 1991, The Battle of Saltville: Massacre or Myth?: Blue and Gray Magazine, August, 1991, pp. 10-19,

46-60.

Marvel, William. Southwest

Virginia in the Civil War: The Battles for Saltville. H.E.

Howard, Inc;

Lynchburg, VA: 1992.

Mays, Thomas D. The Saltville

Massacre. McWhiney Foundation Press; Abilene, TX:

1998.

McDonald, J. N., 1984, The Saltville, Virginia locality: A summary of research and field trip guide: Symposium on the Quaternary

of Virginia, Charlottesville, p. 45.

McDonald, J. N., 1985, A survey and inventory of archaeological resources in the Town of Saltville,

Virginia: A report of activities and results: Report

submitted to the Town of Saltville, p. 69.

Mosgrove, George D. Kentucky Cavaliers

in Dixie. McCowat-Mercer Press, Inc.

Jackson, TN: 1957.

Rachal, W. M. E., 1953, Salt the South could not savor: Virginia Cavalcade,

v. 3, pp. 4-7.

Roanoke Times, 1996, Saltville site find may be oldest ever: Roanoke Times,

Friday, April 12, 1996, p. A1.

Saltville Historical Foundation, undated, Saltville and the Civil War: Informational

brochure published by the Saltville Historical Foundation, Saltville.

“Saltville, Virginia.” The Making of America.

University of Michigan,

online source.

www.makingofamerica.com

Sarvis, W., 1998, The Salt Trade of Nineteenth Century Saltville, Virginia: Will Sarvis, Columbia, MO, p. 85.

Smith, John D. Black Soldiers

in Blue: African American Troops in the Civil War Era., University

of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill,

NC: 2002.

Weaver, Jeffrey C. The Virginia Home Guards. H.E.

Howard Inc, Lynchburg, VA:

1996.

Weaver, Patti O. and John C. Weaver.

Reserves: The Virginia Regimental Histories Series., H. E. Howard Inc., Appomattox, VA:

2002.

Whisonant, R. C., 1996, Geology and the Civil War in southwestern Virginia: The

Smyth County salt works: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources, Virginia Minerals,

v. 42, n. 3, p. 21-30.

Wise, John S. The End of an Era.

Houghton Mifflin Company; New York: 1899.

|