|

3rd North Carolina Mounted

Infantry Regiment, U.S.

A.K.A. Union 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry Regiment; 3rd North Carolina (Federal) Mounted

Infantry Regiment; 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry Regiment, U.S.A.; 3rd North Carolina Mounted, United States;

and Kirk's Raiders.

|

13 June 1864 . . . . . .Raid

on Camp Vance (Morganton, N.C.) |

|

Sept 1864 . . . . . . .

.Bull's Gap |

|

29 Dec 1864 . . . . . .

Skirmish at Red Banks of Chucky |

|

Feb-Mar 1865 . . .. . .Raid on

Waynesville, N.C. |

|

24 Mar 1865 . . . . . . Stoneman's Raid |

On February 13, 1864, Maj. Gen. Schofield authorized Major George W. Kirk,

Second North Carolina Mounted Infantry, to raise a regiment of troops in eastern Tennessee and western North Carolina, to

be known as the Third North Carolina Mounted Infantry Regiment. Although the regiment was organized as infantry, Maj. Kirk

was authorized to mount the regiment upon private or captured horses. The first company was actually organized on June 11,

1864.

By April of 1864, Kirk, now colonel of the Third, was operating in the

Shelton Laurel area of Madison County, N.C. On June 13, 1864, began the Third's best known exploit, the raid on Morganton.

| Kirk's Raiders |

|

| Kirk's Raiders |

On June 13, 1864, Col. Kirk with about 130 men left Morristown, TN., for a

raid on Camp Vance, near Morganton, N.C. The soldiers traveled on foot through Bull's Gap, Greeneville, and Crab Orchard,

TN. They crossed into North Carolina and forded the Toe River about six miles south of the Cranberry Iron Works. The crossed

the Linville River on the afternoon of June 26 and crossed Upper Creek at nightfall on June 27. They marched all night and

reached Camp Vance at reveille on June 28. Camp Vance was a training camp for conscripts; the reluctant soldiers had not yet

been issued rifles. The camp surrendered, and 40 of the conscripts promptly enlisted under Col. Kirk. All except the sick

and the medical officers were carried off to Tennessee. The medical officers were paroled, but the sick (approximately 70

men) were set free because the Federal soldiers had no time to parole them. One Confederate report implies that the "sick"

weren't really ill, but were put on the sick list and admitted into the hospital in a successful effort by the medical officers

to prevent their capture. According to one of the Confederate medical officers, "Col. Kirk claimed to be a regular U.S. Officer,

carried a U.S. Flag, and his men were all in Federal uniforms." Another Confederate report of this incident says that most

of Kirk's men were armed with Spencer repeating rifles. Despite several small skirmishes on the way, Kirk and his men and

prisoners returned safely to Tennessee.

| High Resolution Map of NC Civil War Battles |

|

| 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry Regiment |

Recommended Reading: A History of the North Carolina Third Mounted Infantry

Volunteers: March 1864 to August 1865. Description: A History of the North

Carolina Third Mounted Infantry Volunteers: March 1864 to August 1865 - Ron V. Killian. For years

preceding the Civil War, the mountain people of western North Carolina

lived under very different social and economic conditions than their plantation farming counterparts in other parts of the

state. The mountain people did not generally own slaves, making them reluctant to contribute soldiers when North

Carolina seceded from the Union. Many of these pro-Union Carolinians took up

arms as Federal troops and engaged in guerrilla raids to disrupt Confederate operations within their home state. Continued

below…

The Third Mounted Infantry was one such unit, organized under Col. George

Washington Kirk in February 1864. Ron V. Killian's history discusses the brief but sensational career of the Third Mounted

Infantry from its inception up to the occupation of Asheville, NC in 1865. Until now, little material has been published on

the role of the Third Mounted Infantry in the pacification of the Tennessee/North Carolina mountain region. Often erroneously

referred to as "bushwhackers" or "Tories," the patriotic fathers, sons and brothers that composed this regiment rendered commendable

service in the Camp Vance Raid, Stoneman's Raid against Confederate positions in both Tennessee and North Carolina, and various

skirmishes at Morristown, Russellville, Waynesville and Asheville. Detailed accounts of engagements involving the regiment

are supplemented by extensive rosters noting full name, month, year, and place of enlistment, and age at time of enlistment

for officers, staff, private soldiers and musicians. A biographical sketch of Col. Kirk is also included.

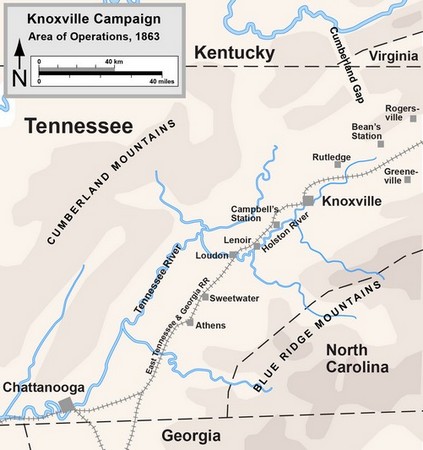

In late September of 1864, Col. Kirk and his command were left at Bull's Gap

to hold that position while the rest of Gen. Gillem's force drove Confederate forces from Rheatown, Greeneville, and Carter's

Station across the Watauga River. By late October, 1864, Confederate scouts were reporting that Kirk and his men had returned

to Knoxville.

On December 9, 1864, the Third left Knoxville on a scout into upper East Tennessee. On December 29th, they engaged a body of about 400 Confederate infantry and

cavalry under the command of Col. James Keith at Red Banks of Chucky near the North Carolina line. (With Keith in command,

no doubt a portion of this body was the 64th North Carolina.) Col. Kirk reported 73 Rebels killed and 32 captured, with his own casualties

limited to three wounded. They returned to Knoxville on January 14, 1865.

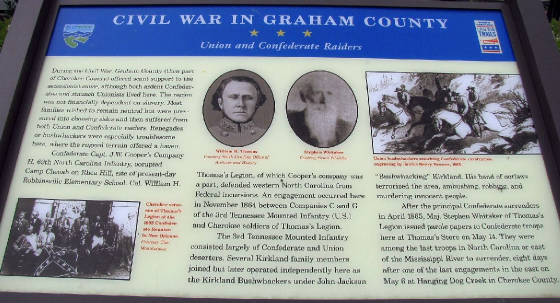

Kirk's Union Mounted Infantry Engage Thomas' Confederate North

Carolina Legion

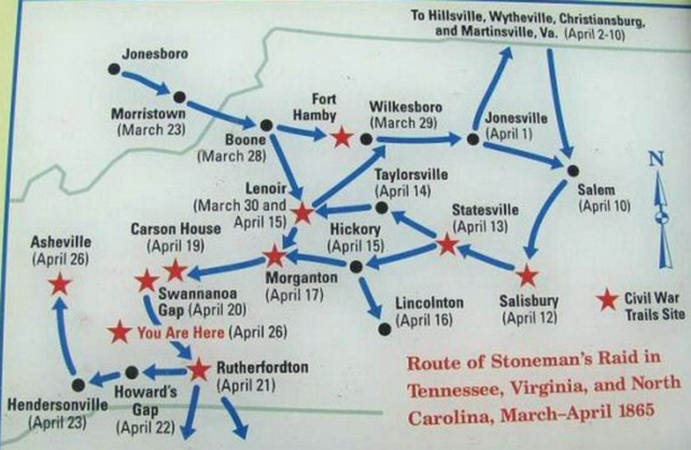

| Route of Union General George Stoneman's Raid |

|

| (Stoneman's Raid Map) |

| Map of East Tennessee Civil War Battles |

|

| Major Battles for East Tennessee in Civil War |

Stoneman's Cavalry Raid and Kirk's Raiders: Civil

War Murders, Depredations, Lawlessness, and Battles

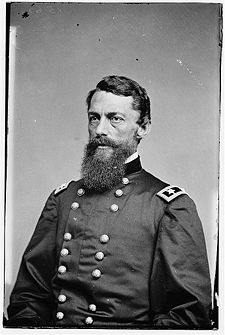

On March 24, 1865, Maj. Gen. George H. Stoneman, initiating Stoneman's Raid, left

Morristown, TN., for a raid through southwest Virginia and western North Carolina. The primary purpose of this operation was

to disrupt the railroads in Virginia and North Carolina and to obstruct Lee's expected retreat from Virginia. As part

of this operation, the 2nd and 3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry under Col. Kirk were sent to Boone, N.C., to hold Deep

and Watauga Gaps, thus keeping open the roads over the mountains to Tennessee to permit the return of Stoneman's force when

its mission was completed.

| General George Stoneman |

|

| (August 22, 1822 - September 5, 1894) |

By 1865

the Confederacy had failed, and Colonel Kirk and the Union's 3rd North Carolina believed it would encounter minimal opposition and resistance as they continued sacking

Western North Carolina communities. Although the Confederacy

was doomed, the Thomas Legion's highest calling had always been protecting North Carolina's mountain citizens. The Thomas Legion was North Carolina's

only Civil War legion, it mustered a massive force of over 2,500 soldiers and consisted of local Highlanders and Cherokee

Indians.

In late

February and early March of 1865, Kirk continued his raids into North Carolina's most

western counties. The Union's 3rd North Carolina was commonly referred to

as Kirk's Raiders because the unit often pillaged and plundered the region.

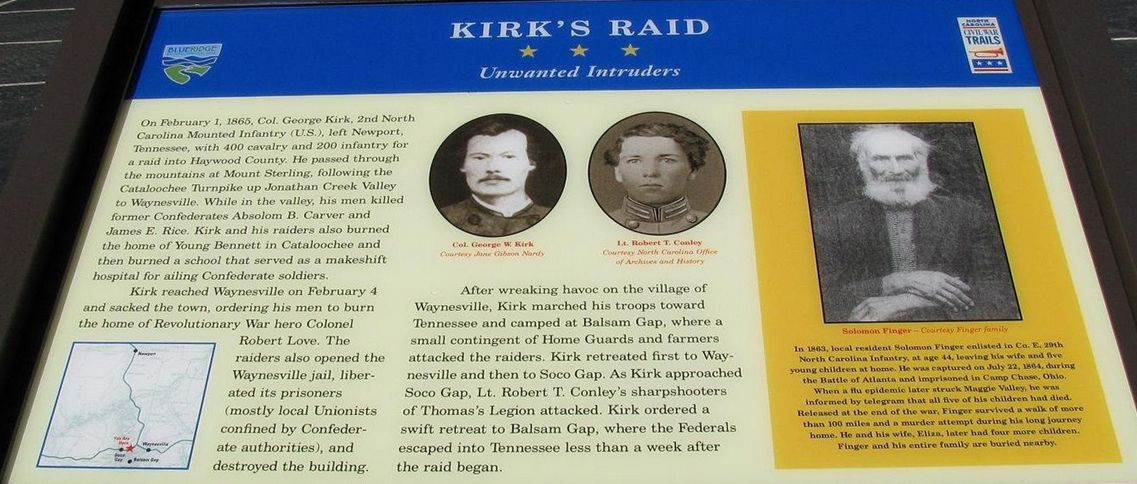

On February 4th, Kirk and a small army of 400 cavalry and 200 infantry left Newport, Tennessee, and crossed into Haywood County, North Carolina, via the "old Cataloochee Turnpike on a raid that reached Waynesville," the

county seat. Kirk's Raiders, now armed with Spencer repeating rifles, entered Waynesville and pillaged stores, stole

as numerous horses, killed 20 men, and burned several houses, including Lt. Col. James R. Love's house-- also

the former residence of James Love's grandfather, the Revolutionary War hero Robert Love. Next, the 3rd Union attacked the Waynesville jail, freed the prisoners, and then burned

the jail.

Slow,

impeded communication, the vastness of rugged Western North

Carolina, and few Home Guard made it extremely difficult to defend the

area. Official Records of the Union and Confederate

Armies, Series I, Volume 32, Part II, p. 553; hereinafter cited as O.R..

Lt. Col. Stringfield, of the Thomas Legion, stated that "it had been reported in Tennessee

that Kirk’s troops would be welcomed in North Carolina.

They were, but with bloody hands to hospitable graves." Lt. Col. Love's Regiment, Thomas' Legion, fought Kirk's Raiders

in Haywood County, and Lieutenant Conley's

Sharpshooters (Thomas' Legion) engaged and forced the enemy to retreat across the Balsam Mountains at Soco Gap, which has an

elevation of 4345 feet and is located 13 miles northwest of Waynesville. The Cherokees refer to Soco Gap as Ahalunun'yi or Ambush

Place.

| Kirk's Raiders repulsed by Conley's Sharpshooters |

|

| Kirk's Raiders |

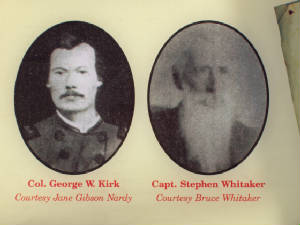

| Col. George Kirk and Captain Whitaker |

|

| Final Surrender Memorial: Franklin N.C. |

On the

morning of March 6th, Lt. Col. Stringfield and a "battalion with many Cherokees

from Jackson and [present-day] Swain Counties" engaged the retreating Kirk's Raiders at Soco Creek (the Cherokees call it

Sagwa'hi or One Place),

thence, forcing them across the Smoky Mountains towards Sevierville, Tenn. The Confederates claimed to have killed a few Federals,

wounded several, and captured some horses. Thomas' Legion had Kirk in a "box," but fortunately for the Federals

each soldier in the legion only had about five bullets. More ammunition just may have alterted the lineage of Kirk and many

of his faithful troops.

Kirk also

hoped to capture Thomas during his many Western North Carolina

raids. At Soco Gap and Soco Creek, however, the soldier that was almost captured, killed, or even scalped was Kirk. This

was Kirk's hardest fighting in Western North Carolina and sent a resounding message that

Thomas' Legion was still a "force of reckoning."

In April 1865, according to O.R., 1, 49, pt. II, pp. 407-408, General Davis Tillson (Stoneman's Raid) ordered Colonels Bartlett (Union's 2nd North Carolina Mounted Infantry) and Kirk (Union's

3rd North Carolina Mounted Infantry) to advance through Western North Carolina and suppress the remaining Confederate

forces in the mountains. General Tillson had attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and because of a severe

foot injury his foot was amputated and, subsequently, he left West Point.

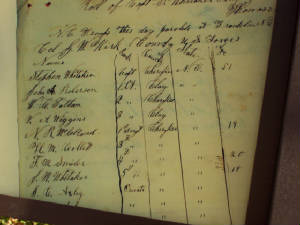

| Parole Signatures of Company E, Walker's Battalion |

|

| East of the Mississippi, Final Confederate Surrender Memorial: Franklin, N.C. |

Lieutenant Robert T. Conley and Company F, Love's Regiment, Thomas' Legion would soon engage Union Colonel Bartlett's 2nd North Carolina at Waynesville. And during the night of May 6, 1865, while Bartlett and his men enjoyed

the spoils of Waynesville, they would find themselves surrounded by both the Cherokee Battalion and Love's Regiment. On May 12, 1865, Col. Kirk would accept the surrender of Walker's Battalion, Thomas' Legion of Cherokee Indians and Highlanders under the command of

Captain Stephen Whitaker at the Macon County Court House in Franklin, N.C. This was the last formal surrender

of Confederate forces east of the Mississippi River, and is commemorated by a mural in the courthouse at Franklin.

Official Order of Surrendering Confederate Forces

On May 10, 1865, Union troops capture Confederate President Jefferson Davis near Irwinville,

Georgia. Cherokee Chief Thomas, the commanding colonel of Thomas' Legion, had surrendered on May 9, 1865.

May 12, 1865, was the "The Final Surrender" for Thomas' Legion. The First Battalion's Company E soldiers signed the parole papers beginning on May 12, with the last signature recorded on May 14, 1865.

Captain Whitaker and Company E, First Battalion of Thomas' Legion were stationed at nearby Franklin, North Carolina. Whitaker and his company had

recently Skirmished at Hanging Dog, Cherokee County,

and were advancing toward White Sulphur Springs to reinforce Thomas when they were intercepted. General Tillson had ordered

Colonel Kirk and the Union 3rd North Carolina to Franklin (O.R., 1, Vol. 49, pt. II, p. 689), and, when they approached the battalion, Whitaker formed a skirmish line. Consequently, he received word of Thomas and Martin surrendering at Waynesville, and then

Whitaker and his company also surrendered. On May 14, 1865, the Legion's soldiers finished

signing the paroles and they viewed Whitaker roll them up, tie them, place them in a Haversack, and give them to Col.

Kirk's Courier.

"And thus at 10 o'clock in the morning of May 14, 1865, our Civil War Soldier Life ended

and our Every Day Working Life began," exclaimed John H. Stewart of the Thomas Legion. The soldiers surrendered to Kirk

understanding that additional fighting was futile and senseless, and finally the aftermath embraced the region. The Union forces never subjugated Western North Carolina, and

to this day the Eastern Band of Cherokee bestows honor and gratitude to their great white chief.

Recommended Reading: East Tennessee and the Civil War (Hardcover)

(588 pages). Description: A solid social, political, and military history, this work

gives light to the rise of the pro-Union and pro-Confederacy factions. It explores the political developments and recounts

in fine detail the military maneuvering and conflicts that occurred. Beginning with a history of the state's first settlers,

the author lays a strong foundation for understanding the values and beliefs of East Tennesseans. He examines the rise of abolition and secession, and then advances into

the Civil War. Continued below...

Early in the

conflict, Union sympathizers burned a number of railroad bridges, resulting in occupation by Confederate troops and abuses

upon the Unionists and their families. The author also documents in detail the ‘siege and relief’ of Knoxville.

Although authored by a Unionist, the work is objective in nature and fair in its treatment of the South and the Confederate

cause, and, complete with a comprehensive index, this work should be in every Civil War library.

Advance to:

Recommended Reading: Bushwhackers, The Civil War in North

Carolina: The Mountains (338 pages). Description: Trotter's book (which could have been titled "Murder, Mayhem, and Mountain

Madness") is an epic backdrop for the most horrific murdering, plundering and pillaging of the mountain communities of

western North Carolina during the state’s darkest hour—the American Civil War. Commonly referred to as Southern

Appalachia, the North Carolina and East Tennessee mountains

witnessed divided loyalties in its bushwhackers and guerrilla units. These so-called “bushwhackers” even used

the conflict to settle old feuds and scores, which, in some cases, continued well after the war ended. Continued below...

Some bushwhackers were highly organized ‘fighting guerrilla units’ while others were

a motley group of deserters and outliers, and, since most of them were residents of the region, they were familiar with

the terrain and made for a “very formidable foe.” In this work, Trotter does a great job on covering the many

facets of the bushwhackers, including their: battles, skirmishes, raids, activities, motives, the outcome, and even the aftermath.

This book is also a great source for tracing ancestors during the Civil War; a must have for the family researcher of Southern Appalachia.

Recommended Reading: The Civil War in North

Carolina. Description: Numerous battles and skirmishes

were fought in North Carolina during the Civil War, and

the campaigns and battles themselves were crucial in the grand strategy of the conflict and involved some of the most famous

generals of the war. Continued below...

John Barrett presents the complete story of military engagements and battles across the state, including

the classical pitched battle of Bentonville--involving Generals Joe Johnston and William

Sherman--the siege of Fort Fisher, the amphibious campaigns on the

coast, and cavalry sweeps such as General George Stoneman's Raid. "Includes cavalry battles, Union Navy

operations, Confederate Navy expeditions, Naval bombardments, the land battles... [A]n indispensable edition." Also

available in hardcover: The Civil War in North Carolina.

Recommended Reading: East Tennessee and the Civil War (Hardcover: 588 pages). Description: A solid social, political, and military history, this work gives light to the rise of the pro-Union

and pro-Confederacy factions. It explores the political developments and recounts in fine detail the military maneuvering

and conflicts that occurred. Beginning with a history of the state's first settlers, the author lays a strong foundation for

understanding the values and beliefs of East Tennesseans. He examines the rise of abolition and secession, and then advances into the Civil

War. Continued below...

Early in the conflict, Union sympathizers burned a number of railroad

bridges, resulting in occupation by Confederate troops and abuses upon the Unionists and their families. The author also documents

in detail the ‘siege and relief’ of Knoxville. Although authored by a Unionist, the work is

objective in nature and fair in its treatment of the South and the Confederate cause, complete with a comprehensive index,

this work should be in every Civil War library.

Recommended Reading:

North Carolinians in the Era of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Description: Although

North Carolina was a "home front" state rather than a battlefield

state for most of the Civil War, it was heavily involved in the Confederate war effort and experienced many conflicts as a

result. North Carolinians were divided over the issue of secession, and changes in race and

gender relations brought new controversy. Blacks fought for freedom, women sought greater independence, and their aspirations

for change stimulated fierce resistance from more privileged groups. Republicans and Democrats fought over power during Reconstruction

and for decades thereafter disagreed over the meaning of the war and Reconstruction. Continued below...

With contributions

by well-known historians as well as talented younger scholars, this volume offers new insights into all the key issues of

the Civil War era that played out in pronounced ways in the Tar Heel State.

In nine fascinating essays composed specifically for this volume, contributors address themes such as ambivalent whites, freed

blacks, the political establishment, racial hopes and fears, postwar ideology, and North Carolina women. These issues of the

Civil War and Reconstruction eras were so powerful that they continue to agitate North Carolinians today.

Recommended Reading: Bluecoats and Tar Heels: Soldiers and Civilians in Reconstruction North

Carolina (New Directions in Southern History) (Hardcover). Description:

In Bluecoats and Tar Heels: Soldiers and Civilians in Reconstruction North Carolina, Mark L. Bradley examines the complex

relationship between U.S. Army soldiers and North Carolina civilians after the Civil War. Continued below...

Postwar violence and political instability

led the federal government to deploy elements of the U.S. Army in the Tar Heel State, but their twelve-year occupation was marked by uneven success: it proved more

adept at conciliating white ex-Confederates than at protecting the civil and political rights of black Carolinians. Bluecoats

and Tar Heels is the first book to focus on the army’s role as post-bellum conciliator, providing readers the opportunity

to discover a rich but neglected chapter in Reconstruction history.

Sources: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; nctroops.com, Vernon H. Crow,

Storm in the Mountains: Thomas' Confederate Legion of Cherokee Indians and Mountaineers; John H. Stewart Papers (Private

Collection); John G. Barrett, The Civil War in North Carolina; Vernon H. Crow, The Justness of Our Cause; Walter Clark,

Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina in the Great War 1861-1865; National Park Service: Soldiers

and Sailors System; Weymouth T. Jordan and Louis H. Manarin, North Carolina Troops, 1861-1865; E. Stanly Godbolt, Jr. and

Mattie U. Russell, Confederate Colonel and Cherokee Chief: The Life of William Holland Thomas; The Thomas Legion Papers (thomaslegion.net/papers.html); The Civil War Diary of William W. Stringfield, Johnson City, TN: East Tennessee Historical Society Publications; D.

H. Hill, Confederate Military History Of North Carolina: North Carolina In The Civil War, 1861-1865; North Carolina Division

of Archives and History; National Archives and Records Administration; Library of Congress; State Library of North Carolina;

North Carolina Museum of History; Digital Library of Georgia; Museum of the Cherokee Indian; Official Website of the Eastern

Band of Cherokee Nation; Duke University; University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill); University of Tennessee (Knoxville);

Tennessee State Library and Archives; Western Carolina University; North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources; John

R. Finger, The Eastern Band of Cherokees.

|