|

Shiloh Battle and Campaign

by Matthew Forney Steele

Lieutenant

Colonel, U. S. Army, Retired

American Campaigns

War Department Document No. 324, Office of the

Chief of Staff

Published in 1909

Compiled from lectures over three years at the Army Service Schools at Fort Leavenworth,

Kansas

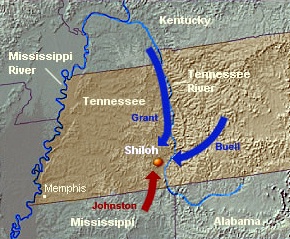

| Shiloh Civil War Battle and Campaign Map |

|

| Shiloh Civil War Battlefield Map |

At the end of the campaign of Forts Henry and Donelson we left General Albert

Sidney Johnston, with the remnant of his army, at Murfreesboro; Buell's

army, 50,000 strong, was concentrating at Nashville; and Grant

had 40,000 troops at the two captured forts. Beauregard, with his headquarters at Jackson,

was in immediate command of Johnston's troops between the Mississippi

and the Tennessee. The bulk of these, some 17,000, were

at Columbus under Polk. Other small garrisons held the Confederate

posts along the Mississippi as far down as Memphis; and there

were detachments at Corinth and luka, with outposts watching the Tennessee

River. Threatening Columbus and the posts along the Mississippi, General Pope had a command of about 25,000 Federals

at Commerce, on the right bank of the Mississippi; and Generals Van Dorn and McCulloch had some 20,000 Confederates in northern

Arkansas, opposed to a Union force under General Curtis.

Grant's troops had destroyed the railway bridge above Fort

Henry, and the Federal gunboats controlled the Tennessee River

as far up as Muscle Shoals. Johnston's army was thus cut in two; the two wings could unite

only somewhere south of the Tennessee River. Beauregard appreciated the situation, and urged

Johnston to assemble his scattered troops in the neighborhood of Corinth. He and Johnston made every exertion to increase the strength of their forces, and

the Confederate government at Richmond seconded their efforts.

Bragg with a force of about 10,000 men was ordered from Pensacola to Corinth;

as was, also, Van Dorn from Arkansas. Troops were sent thither,

also, from New Orleans and other places.

On the 28th of February 1862, Johnston began

his march from Murfreesboro to Corinth, by way of Decatur, Ala., where a bridge spanned the Tennessee. He had with him about 17,000 men organized in three small divisions, with a "reserve"

under General Breckinridge. His command included several regiments of cavalry. On the 2d of March Polk evacuated Columbus, and withdrew the greater part of his garrison to the railway

junction at Humboldt. About 7,000 men under McCown were left in the works at New Madrid and Island No. 10 to guard the Mississippi, which was still held by the Confederates from this point to Vicksburg.

Buell, foreseeing that Johnston would undertake to reunite the separated

wings of his army by way of the Memphis and Charleston Railway south of the Tennessee River, believed that his army and Halleck's

should join at some point on the north bank of that river, between Savannah and Florence, and from thence seize the Memphis

and Charleston Railway. His object was to unite his own and Halleck's forces under cover of the Tennessee,

then to cross the river and defeat Johnston's main army; he believed this would cause the abandonment

of the posts up the Mississippi, and the opening of that river. Halleck, on the other band, gave no thought to

Johnston's main army at first. His mind always turned to strategic

points rather than to the hostile army. Memphis was the objective

upon which his thoughts now fixed. Before forming any plan for its capture he seemed to have designed first to destroy

its railway connections with the Confederate post at Columbus

and with the east.

Accordingly

he issued orders on the 1st of March for Grant, with a force of 35,000 troops, to move up the Tennessee in transports. Owing to a misunderstanding between Grant and Halleck, Grant was

later ordered to remain at Fort Henry;

and the expedition was commanded by General C. F. Smith. Halleck's instructions to Smith stated: "The main object of this

expedition will be to destroy the railroad bridge over Bear Creek, near Eastport, Miss., and also the connections at Corinth, Jackson, and Humboldt... Having accomplished these objects, or such of them as may be practicable,

you will return to Danville, and move on to Paris."

The expedition soon got off, and, by the 11th of March, the flotilla of

more than eighty transports began arriving at Savannah, where

the depot was to be established. The force was organized in five divisions, under Generals McClernand, W. H. L. Wallace, Hurlbut,

W. T. Sherman, and Prentiss. A sixth division commanded by Lew Wallace arrived later, and was put into camp at Crump's Landing,

six miles below Pittsburg Landing.

A detachment was sent over to tear up a part of the railway track from Jackson to Corinth, and on the 14th Sherman's

division went by boats up to Eastport for the purpose of destroying the bridge over Bear Creek. Sherman was prevented from carrying out his purpose by a very heavy rain which flooded the

country and made the small streams impassable. In the meanwhile Halleck learned of the evacuation of Columbus by the Confederates. Then, for the first time, it seems to have occurred to him

to make the movements up the Tennessee his main operation, of which the object should be

to get between the wings of Johnston's army. He had not yet

determined whether to assail these separate wings in detail, or both at once. In correspondence with Buell he wrote: "Why

not come over and operate with me to cut Johnston's line with Memphis,

Randolph, and New Madrid? . . . Come over to Savannah

or Florence, and we can do it. We can then operate on Decatur or Memphis, or both, as may appear

best." His mind still dwelt upon places, strategic points, as objectives, rather than

upon the hostile army. This was the fulfilment of Halleck's notion of strategy.

On the 11th of March President Lincoln placed all of the territory from

Knoxville as far west as the Missouri River, and all the Union

troops therein, under the command of Halleck. This command included Buell's army. Thereupon Halleck ordered Buell to march

his army to Savannah. The Confederate forces were massing

at Corinth, twenty-two miles in a straight line from Savannah,

on the opposite side of the Tennessee. Already about 23,000

Confederates were there, or "within easy marches of Corinth," not including the troops that

Polk had withdrawn from Columbus. They had not yet arrived.

General Johnston reached Corinth on the 22d

of March; by the end of the month all of the Confederate troops who took part in the battle of Shiloh, some 40,000, were concentrated

about Corinth. Van Dorn's command, from Arkansas, did not arrive in time for the battle. Johnston

organized his forces, designated the "Army of the Mississippi,"

into three corps, under the command, respectively, of Major Generals Polk, Bragg, and Hardee, with a reserve of two brigades

under Major General Breckinridge. Beauregard was to be second in command, and Bragg, besides commanding a corps, was appointed

Chief of Staff by Johnston.

Instead of camping his army at Savannah,

General Smith, with the authority of Halleck, had selected a place nine miles higher upstream, and on the opposite bank, known

as Pittsburg Landing. Here this Union army was in camp, awaiting the arrival of Buell's forces. General Smith having gone

on sick report, on account of an injury from which his death resulted a short while afterward, Grant was restored to the command

of the army, and rejoined it on the 17th of March. He made his headquarters at Savannah,

instead of at Pittsburg Landing.

The ground upon which the Union camps stood, and upon which the battle of

Shiloh took place, was twenty-two miles by road northeast of Corinth.

It was an irregular triangle, with sides three or four miles long, bounded on the east by the Tennessee [River], which here

flows due north; on the northwest by Snake Creek and its branch, Owl Creek; and on the south by Lick Creek and its branch,

Locust Grove Creek, a small brook in a considerable ravine.

The highest ground was a ridge lying north of Locust Grove Creek, and extending

on toward the west. Its top was 200 feet above the river, and its northern slopes fell gradually to the level of the camps,

100 feet lower. In the hollows of these slopes the branches of Owl Creek found their headwaters. The most important of these

branches was Tillman (Tilghman) Creek, whose deep hollow, running north, a mile and a quarter from the river, divided the

space into two main plateaus. These plateaus were broken into smaller tables and undulations by the surface drains and ravines

of the smaller watercourses. At the time of the battle the ground generally was in forest, partly open, but partly impassable

for horsemen, with, here and there, clearings of twenty to eighty acres.

Several roads traversed the battlefield. One, the Hamburg-Savannah Road, usually spoken of as the River

Road, led from Crump's Landing, six miles downstream, and, crossing Snake Creek by a bridge, continued

on southward along the eastern plateau. At the eastern end of the ridge north of Locust Grove Creek it forked with the Purdy-Hamburg Road. This road, coming in from Purdy by a bridge

over Owl Creek, continued southeasterly along the high ground, and, crossing Lick Creek a mile from its mouth, led to Hamburg,

three or four miles farther up the river.

Pittsburg Landing was three-quarters of a mile below the mouth of Snake

Creek. From this landing two roads led to Corinth. One, called

the Eastern Corinth Road, followed the backbone of

the ridge beyond the headwaters of Locust Grove Creek, and joined the Bark Road;

the other, a mile farther west, ran nearly parallel to the Eastern Corinth Road

for about four miles, and was known as the Western Corinth Road.

There were other by-roads and trails through the timber. Shiloh Church,

the little log meeting-house that gave its name to the battle, stood above the bank of Oak

Creek..., at the fork of the Western Corinth Road

and the Purdy Road.

On this ground the Union army was encamped by divisions. One of Sherman's brigades was on the extreme right front, along the Purdy Road, and guarding the bridge over Owl Creek. Two others

were astride the Western Corinth Road just at Shiloh Church, and behind the ravine of Oak Creek. Stuart's brigade of this division was on the extreme left-front, at the junction

of the Purdy-Hamburg Road and the River Road, near the end of the ridge above Locust Grove Creek.

Prentiss's camp occupied the middle-front and was across the Eastern Corinth Road. McClernand's formed an angle at the junction

of the Hamburg-Purdy Road with the Western Road. It was about 500 yards behind the left of Sherman's tents. Hurlbut's camp was a mile and a half behind that of Prentiss, at the junction

of the River Road and the Eastern Road. W. H. L. Wallace's was in the angle of these two roads, a mile in rear

of Hurlbut's. Lew Wallace's division was still camped at Crump's Landing.

Although it was known that Johnston was assembling

an army at Corinth, where it was estimated that there were

already 50,000 to 80,000 Confederates, no works of any kind were thrown up about the Federal position; nor was any line of

defense or plan of action in case of attack arranged. The various camps were established with reference to the convenience

of the different commands, and without any system. There were no cavalry outposts between the camps and Corinth. "Probably there never was an army encamped in an enemy's country with so little

regard to the manifest risks which are inseparable from such a situation." True, the 5th Ohio Cavalry often reconnoitered some miles to the front, and frequently

encountered parties of hostile cavalry.

Johnston and Beauregard appreciated the faultiness, strategical and tactical,

of the position of Grant's army, in a pocket between Snake Creek and Lick Creek, with an impassable river behind it. The position could have been made impregnable by earthworks in one night; but the Confederate commanders were aware that it had not been intrenched. They

resolved to attack Grant's exposed army before Buell's should join it. They hoped to move on the 1st of April; but, owing to delay in Johnston's arrival, and in the organization of the forces, due mainly to the inexperience

of officers and men, the army did not begin its advance until the afternoon of the 3d. It had, then, to go without Van Dorn's

command, 20,000 strong, which was delayed in Arkansas by

high water.

The order for the march directed that it should begin at noon; the army

was to be in position, deployed for attack, at 7:00 a. m. on the 5th. The distance to march was only about eighteen miles,

but there were only two narrow earthen roads, through dense forests. Many of the troops were raw; Bragg's corps had never

made a march before. There was misunderstanding and delay at the very beginning of the journey. The heads of the two main

columns did not start until late in the afternoon. On the 4th the march was slow and confused. Instead of reaching the position

from which the attack was to be launched, at the hour appointed, 7:00 a. m. April 5, it was 4:00 p. m. before the army was

deployed. It was then too late in the day to begin the attack, which was postponed to daybreak of the 6th.

Johnston's army was now within two

miles of Shiloh Church, Sherman's headquarters. A body of Confederate cavalry had foolishly pushed forward so boldly

that it ought to have warned the Federal commanders that there was a strong force close behind it. Yet no warning was taken by the Federals. Saturday, the 5th, the Union cavalry

and artillery spent the day moving their camps, in obedience to an order changing their assignments.

The advanced Confederate cavalry had already been encountered by small exploring

parties of Union troops. On the 3d, also, Buckland's brigade, sent out by Sherman,

had met Confederate cavalry six miles from the Union camp, and had then returned to camp. The next day, the 4th, a picket

of the same brigade was captured by this cavalry, and later in the day Major Lockett and a party, sent to rescue the picket,

were also captured. Two of Sherman's brigade commanders, Buckland

and Hildebrand, visited their outposts on Saturday, the 5th, and saw parties of hostile cavalry hovering in the woods beyond.

Some of the sentinels claimed that they had seen infantry. Numbers of rabbits and squirrels were noticed scudding from the

woods in front of the camps. This was all reported to Sherman,

but he had no cavalry to send out to reconnoiter--due to the exchange of the regiments then taking place.

Saturday afternoon Prentiss, in consequence of reports from his outposts,

sent out three companies to reconnoiter. They marched three miles, but, taking the wrong direction, passed along in front

of Sherman's outposts instead of encountering the Confederate

line, which was less than two miles in front. McClernand, and McPherson, then chief engineer of this army, the same day rode

with an escort of cavalry toward Hamburg. They saw a few

hostile scouts.

Patrols from Lew Wallace's division at Crump's Landing developed a considerable

force of the enemy at Purdy and Bethel. It was Cheatham's

division at those points making ready to march to the Confederate assembly for battle. Informed of this, General Grant rather

looked for an assault on Lew Wallace's camp, and gave orders for supporting Wallace in such an event. Saturday Sherman wrote

Grant: "All is quiet along my line now.... The enemy has cavalry in our front, and I think there are two regiments of infantry

and one battery of artillery about six miles out.... I have no doubt that nothing will occur today more than some picket-firing.

The enemy is saucy, but got the worst of it yesterday, and will not press our pickets far. I will not be drawn out far, unless

with certainty of advantage; and I do not apprehend anything like an attack on our position." On the same day Grant, in reporting

events by wire to Halleck, said: "I have scarcely the faintest idea of an attack (general one) being made upon us, but will

be prepared should such a thing take place. General Nelson's division has arrived. The other two of Buell's column will arrive

to-morrow or next day. It is my present intention to send them to Hamburg....

From that point to Corinth the road is good, and a junction can be formed with the troops from

Pittsburg at almost any point." Earlier in the day Grant had

telegraphed: "The main force of the enemy is at Corinth, with

troops at different points cast. Small garrisons are also at Bethel, Jackson, and Humboldt.... The number of the enemy at Corinth,

and within supporting distance of it, cannot be far from 80,000."

General Halleck expected to take command, in person, of the combined forces

of Grant and Buell in a few days, and move them on Corinth.

Johnston's

army bivouacked in order of battle the night of April 5, 1862. It was formed in three lines, with Hardee's corps and one brigade

of Bragg's in the first line, the rest of Bragg's corps in the second line, and Polk's corps and Breckinridge's division in

the third line.

About 3:00 a. m. on Sunday, the 6th of April, three companies of the 25th

Missouri started out from Prentiss's division on a reconnaissance.

They struck the Confederate outposts in front of Sherman's

camp at 5:15 o'clock. Before 6:00 the Confederate lines began to advance; by 6:30 they had reached the line of the Union outposts,

a mile in front of the camps. At 6:00 o'clock the 21st Missouri,

from Prentiss's division, moved to the front. It encountered the Confederate line about a half mile from camp, and was driven

back.

The direction of Johnston's advance brought

Hardee's line first against the right of Prentiss's division and the left of Sherman's.

These divisions formed for battle as soon as they were warned of the attack upon their outposts. They were composed of raw

troops who had never been under fire before. After a short stand Sherman's

left regiment broke and fled to the rear. A little later the other two regiments of his left brigade, Hildebrand's, did likewise.

The first and second lines of the Confederates, struggling through the thick

woods, were soon commingled. They became engaged along their whole front. At 7:30 Beauregard ordered Polk and Breckinridge,

of the third line, to hasten forward, Polk to the left and Breckinridge to the right.

McClernand formed his division on the left of Sherman, and Hurlbut sent one of his brigades to their aid. Hurlbut moved his other two brigades

toward the gap between the left of Prentiss and the right of Stuart.

The division of Prentiss, which had formed line of battle a quarter of a

mile in front of its camp, was the first whole division of the Union line to give way. About 9:00 o'clock it broke and fell

back in confusion. Prentiss rallied about 1,000 of his men upon a line that W. H. L. Wallace and Hurlbut were forming, with

parts of their divisions, in a strong position in rear. "Its peculiar feature consisted in a wood in the center, with a thick

undergrowth, flanked on either side by open fields, and with open, but sheltering, woods in front and rear." The Confederates

gave this place the name of "Hornets' Nest."

At 8:30 a. m. W. H. L. Wallace had moved his division from its camp, sending

two regiments to help Stuart, on the left; one to Sherman;

and two to guard the Snake Creek bridge. Two brigades he was forming on the right of the line at the Hornets' Nest. Hurlbut

was forming on his left. Prentiss rallied his men on the center of their line, and took position on the summit of a slope

covered by a dense thicket. His right was near the Eastern Corinth Road,

and his line was partly in an old sunken road running northwest.

Between 10:00 and 11:00 o'clock Sherman's

division, hard pressed by the enemy, and now reduced to two brigades, badly broken and disordered, fell back to a new position

in rear of the Purdy road. Soon afterward McClernand's division, both of whose flanks were now uncovered and enveloped, also

fell back. It formed a new line between Sherman's left and W. H. L. Wallace's right. Hurlbut was also pushed back.

About noon a strong brigade from the Confederate third line turned Sherman's right, while two other brigades pressed his front. Sherman's battered regiments made a stout fight; but they were gradually

forced to the left and rear. About 1:00 o'clock, during a lull, Sherman

moved his shattered command still farther in the same direction, and took a position covering the River Road, by which Lew Wallace was expected to bring his division into the battle.

In like manner McClernand's division had been outflanked and beaten back step by step. It made its ninth and final stand with

its right joining the remnant of Sherman's division.

At 3:00 o'clock, or thereabouts, the extreme left of the Union line, which

had been pressed back from one position to another, was finally enveloped and forced to give way altogether. This exposed

Hurlbut's left flank to an overwhelming force of the enemy, under the personal command of General Bragg. Hurlbut and Prentiss

and W. H. L. Wallace had successfully held their ground at the Hornets' Nest for five hours. One body of Confederates after

another had assaulted them, only to be repulsed with heavy loss. Divisions and brigades from every one of the Confederate

corps had striven in vain to carry the position. General Johnston, personally, had led one of the regiments in its assault;

and it was in the open ground on the cast flank of the Hornets' Nest that he received the wound from which he died at 2:30.

Seeing his flank turned and his rear about to be assailed, Hurlbut withdrew

his troops. As the last of his regiments were retiring, the left of the Confederate line, under Hardee, which had driven back

Sherman and McClernand, was swinging around from the north. It joined flanks with Bragg's line from the south, and these two

bodies were now forming a circle of fire around Wallace and Prentiss, at the Hornets' Nest. At this juncture Wallace faced

his regiments about. He was killed; but two of his regiments charged to the rear, and, cutting their way through the enemy,

marched to the landing. Prentiss, with the fragments of his own and Wallace's divisions, made a desperate stand. It was hopeless;

after nearly an hour more of fierce struggle he surrendered with 2,200 men to overwhelming numbers.

Seeing the Union lines drifting back, Colonel Webster of Grant's staff had

collected all of the available artillery, about forty or fifty pieces, including some siege guns, at a commanding position,

on the north side of the ravine at the head of Dill's Branch, about a half mile from the landing. Hurlbut, after his withdrawal

from the line at the Hornets' Nest, rallied his troops behind these guns. Other detachments joined him there, making altogether

a force of some 4,000 men. Two Federal gunboats at the mouth of the creek lent their aid, also; but the muzzles of their guns

had to be raised so high to clear the bluff that most of the shells fell far away in the woods.

Bragg tried to gather together a force in order to assault this position.

In the confusion incident to Prentiss's surrender at the Hornets' Nest he could muster only two brigades, those of Jackson

and Chalmers. These moved into the ravine in front of Hurlbut's line. Meantime Beauregard, who was now in chief command of

the Confederates, had sent out the order, from his position at Shiloh

Church, to suspend the attack. Jackson's

brigade received the order before it advanced, and did not assault; Chalmers charged with his brigade alone, and was repulsed.

Thus ended, at dusk, the first chapter in the bloody battle of Shiloh.

Nelson's division of Buell's army, for lack of a guide to show it the way,

and on account of the bad road, bad taken all day to march from Savannah.

One, only, of his brigades, Ammen's, was ferried across the river just in time to see the end; it had two men killed and one

wounded. It went into position near Colonel Webster's guns; the rest of the division formed there as it arrived, and the division

bivouacked there.

Hurlbut's troops, with some men of the divisions of W. H. L. Wallace and

Prentiss, bivouacked about the position they held at the end of the battle. McClernand's shattered division was on their right;

and Sherman's command, which, he says in his report, "had

become decidedly of a mixed character," prolonged the line of bivouac to the right, on the River Road. Lew Wallace's division, which had taken the wrong road from Crump's Landing

in the morning, finally arrived about dark, and bivouacked along the River Road

on Sherman's right. Crittenden's division of Buell's army

joined during the night; and by 5:00 o'clock Monday morning McCook had, also, arrived with a brigade of his division. Buell

had come in the afternoon. Two other divisions of his army were far behind. Wood's arrived before the close of the second

day's fight, but took little part in it; Thomas's did not reach the field at all during the engagement. Mitchel's division had gone toward Florence.

In obedience to General Halleck's orders the Army of the Ohio

(Buell) had started from Nashville for Savannah

on the 16th of March. At Columbia, on the way, the bridge over Duck River was found in flames, and the river

very high. The bridge had to be rebuilt. This delayed the column at Columbia

until the 30th. The distance from Nashville to Savannah

is about 135 miles; it took Buell's leading division twenty-two days to march it. The journey might have been made in less

time, in spite of the burnt bridge, the high water, and the bad roads; but Halleck had given Buell no word to make haste.

On April 4 Nelson, who commanded the leading division, was notified by General Grant "that he need not hasten his march, as

he would not be put across the river before the following Tuesday [the 8th]."

The Confederates spent the night of April 6 in the abandoned camps of Sherman,

McClernand, and Prentiss, annoyed by shells from the Union gunboats, which were thrown among them at intervals of fifteen

minutes during the whole night. ([Map]87) The organizations were hopelessly scattered and mixed.

General Grant was at breakfast at Savannah,

nine miles by water from Pittsburg, when he first heard the guns in the battle of Shiloh. He sent word at once to Nelson, who had arrived at that point with his division, to march it

immediately to the point opposite Pittsburg Landing; ([Map]87) then he hurried up the river in his boat. On his way he stopped

at Crump's Landing to warn Lew Wallace to be ready to move; from Pittsburg

he dispatched an order to Wallace to march his division to the battle. He then rode out to the front, and "visited" his various

division commanders. He saw Prentiss at the Hornets' Nest, and ordered him to hold his position there at all hazards. We have

seen how Prentiss obeyed the order.

Buell and Grant met, and talked together a little while, on Grant's boat,

at Pittsburg Landing, soon after Buell's arrival. Grant was the senior by recent promotion in the Volunteers (as a reward

for his capture of Forts Henry and Donelson); but he assumed no command over Buell, and gave him no orders. In fact, the two

commanders do not appear to have arranged any concerted plan of action. Buell states that he determined on the evening of

the 6th to attack the Confederates at daybreak on the 7th with his own forces. Grant did not, until the morning of the 7th,

issue any order for his troops to advance.

On this day Beauregard's shattered army was no match for its foe. Every

Confederate regiment had been engaged the day before, and the losses had been heavy in officers and men; about 8,000 had fallen,

killed or wounded. Not many more than 20,000 stood in ranks on the morning of the 7th of April. Opposed to these there were

25,000 fresh troops, Buell's forces and Lew Wallace's division, besides the fragments of Grant's other divisions, perhaps

7,000 men, who had defended themselves so stanchly the day before.

The second day's engagement was brought on by the movement of Nelson's division

along the River Road in line of battle. It encountered

the Confederates a little in advance of Hurlbut's old camp, at 5:20 a. m. Crittenden's division formed on Nelson's right, and McCook's, on Crittenden's

right. Grant's army was on the right of Buell's, with the remnants of the divisions of Hurlbut, McClernand, and Sherman, in

order from left to right, and Lew Wallace's fresh division on the extreme right.

Generals Hardee, Breckinridge, Polk, and Bragg took charge of the portions

of the mixed Confederate line, in the order named, from right to left. The line was forced back step by step, but had not

receded as far as Shiloh Church

by 2:30. Beauregard still had his headquarters in the church, from whence, about that hour, he dispatched his aides to his

several lieutenants with orders to withdraw.

A covering force of some 2,000 men was gathered together and posted on high

ground within sight of the church. By 4:00 o'clock the entire Confederate army, all that was left of it, had retired beyond

this force, and not a single Federal soldier was in pursuit. Breckinridge commanded the Confederate rear guard, "with Forrest's

regiment between him and the enemy." That night the rear guard bivouacked not more than two miles from Shiloh.

The next day (the 8th) Wood's division, and Sherman with two brigades and the 4th Illinois Cavalry, went in Pursuit. Toward

evening they came upon the camp of the Confederate rear guard a few miles from the battlefield. Forrest charged them, putting

the Federal skirmishers to flight, throwing the cavalry into confusion, and effectually putting an end to the pursuit. After this Breckinridge's detachment rested undisturbed within six miles of the

battlefield, while Beauregard's main body retreated to Corinth.

Grant's troops, from the private soldiers up to the highest commanders,

appeared to be content with having recovered their camps; and Buell says that "in some way that idea obstructed the reorganization

of his line, until a further advance that day became impracticable." General Grant says that the roads were so bad from the heavy rains of the night

before and the wheels of the Confederate artillery, and the men were so worn out, some from two days of battle, others from

marching and fighting, he had not the heart to send them in pursuit.

In the battle of Shiloh, General Grant

states, his effective strength in the first day's action was 33,000 men; for the second day's battle Lew Wallace had joined

with 5,000 and Buell with 20,000 fresh troops. The Union loss for the two days was 1,754 killed, 8,408 wounded, and 2,885

captured or missing; a total of 13,047. The effective strength of the Confederate army was between 38,000 and 40,000 men.

Its loss was 1,728 killed, 8,012 wounded, and 959 missing; a total of 10,699. The Federal loss was more than twenty-four per

cent of their effective strength; the Confederate more than twenty-six per cent.

The defeat at Shiloh was not the only Confederate

disaster in the west on the 7th of April. On the same day Island No. 10, with about 7,000 men, surrendered to the combined

land and naval forces under General Pope and Commodore Foote. Pope was thereupon ordered to move his army against Fort Pillow; but before

he had well begun operations against this post he was ordered to transfer his army to Pittsburg Landing.

COMMENTS

The

campaign and battle of Shiloh are the hardest of all the campaigns and battles of the Civil War for the student to solve--to

sift the truth from; the hardest of them all in which to place the little credit that can be found in the generalship on either

side upon the proper commanders; the hardest of them all in which to fix the blame for mistakes. It is not hard for the student

to find abundant faults; it is only hard for him to fix the responsibility for them. And this all arises from the fact that

the generals on each side have fought more bitterly with the pen, among themselves, since the great battle, than they fought,

side by side, against their common foe, during the battle. Grant and Buell have contradicted each other in essential particulars

on one side; on the other Beauregard and the friends of Johnston

have carried on a bitter controversy. About all the student can do is to follow the actual operations as nearly as possible

and determine for himself wherein they were right and wherein they were wrong, without trying to place credit or blame upon

individuals.

Napoleon's Twenty-seventh Maxim says: "When an army is driven from a first

position the retreating columns should always rally sufficiently in rear, to prevent any interruption from the enemy. The

greatest disaster that can happen is when the columns are attacked in detail." This maxim fitted the case of Johnston's army after it was split in two by the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson and the

loss of the direct line of communication between its wings. If General Johnston fully appreciated the importance of reuniting

the wings of his army "sufficiently in rear," and as quickly as possible, he certainly did not show his appreciation by prompt

action. There was no way for him to bring his two separated wings together except to retreat with his own (the right wing)

to the south of the Tennessee River. He reached Murfreesboro

in his retreat from Nashville about the 20th of February, but he did not start from there for

Corinth until the 28th of February. In tarrying for more than

a week at Murfreesboro, Johnston,

no doubt, was influenced by the state of the public mind. Already he had lost Forts Henry and Donelson, the Tennessee

and the Cumberland Rivers, his hold upon

Kentucky, and the important town of Nashville.

To retreat farther was to surrender the whole of Middle Tennessee to the enemy. The newspapers of the South were all decrying

him as a failure, and state delegations were demanding his removal.

After leaving Murfreesboro Johnston's army made the march to Corinth,

by way of Decatur, as rapidly as practicable under the circumstances.

The roads were terribly bad, and the streams all swollen; the distance was something less than 250 miles, and the head of

the column reached Corinth on the 18th of March, having averaged about fourteen miles a day.

For eight or ten days after the fall of Fort Donelson General Halleck does

not appear to have had in mind any definite and comprehensive plan of operations. "I must have command of the armies in the

West," he wrote to the Secretary of War on the 19th and 20th of February--meaning Buell's army in particular--"and I will

split secession in twain in one month." How he meant to go about it does not appear. It is plain, however, that he had

no thought of destroying Johnston's main army; it is probable that the principal thing he had

in mind was to reduce the Confederate forts on the Mississippi,

and open that river to navigation. He virtually did nothing until about the 1st of March, when he dispatched the force up

the Tennessee under C. F. Smith, to break up the railway junctions, then to return by water

to Danville--a sort of steamboat raid.

This led to the selection of Pittsburg

as the camp of Grant's army. Merely as a temporary base from which to make raids against neighboring railway points, this

place was good enough so long as it was known that the enemy was not in force within striking distance. Even then it ought

to have been protected with field works. Soon, however, several things happened to change matters, and to shape General Halleck's

plans. It became known that the Confederates had evacuated Columbus, and moved its large garrison southward on the railway,

and that Johnston was concentrating his scattered forces at Corinth; and, on the 11th of March, Halleck was placed in supreme

command of all the Union forces in this theater. Then the plan of moving against Johnston at

Corinth took form with Halleck, and he ordered Buell to move to Savannah. Although he believed, however, that Johnston had

already assembled from 50,000 to 80,000 troops in the neighborhood of Corinth, he did not enjoin

Buell to march speedily; nor did he order Grant to quit his exposed position at Pittsburg.

He did, however, order him to intrench.

Nor did the peril of their camps at Pittsburg

appeal to General Grant, or to any of his subordinate commanders. That they did not fortify their position may be condoned;

"hiding behind earthworks" had not yet become the fashion. For a commander to intrench his camp in the open, at this time,

would perhaps have been regarded as showing timidity; yet the Confederates had already set Grant and his generals the example

at Donelson, and taught them the defensive strength of field works. The Confederate generals at Corinth were apparently just as careless about the protection of their camps. But that Grant

kept his troops at Pittsburg Landing at all, and that his service of "security and information" was performed so inadequately,

passes one's understanding. Even though neither side had, as yet, learned how to use its cavalry in this kind of work one

cannot understand how Johnston's entire army could bivouac within two miles of Sherman's headquarters without having its presence

discovered, or even suspected, by that general.

The wisdom of President Lincoln's order placing a single general, albeit

the choice fell upon General Halleck, in command of this whole theater of operations, was amply verified in the campaign.

It brought Buell with his army to the field of Shiloh in time to turn a Union defeat into

victory; possibly in time to save Grant's army from capture. After Shiloh it enabled Halleck

promptly to assemble there a splendid army of 100,000 troops, nearly every man of which had been tried by the fire of battle.

In leaving Pope, however, with his five divisions, some 25,000 men, to operate

against New Madrid and Island No. 10, after he had resolved to concentrate against the Confederates at Corinth, Halleck made a mistake. A small "containing" force might have been left to watch

the Confederates at those points; but Pope, with his main body, ought to have been hastened to a junction with Grant and Buell.

A commander should have only one main objective at a time, and he should direct all of his troops, all of his operations,

with reference to that single objective. Johnston's army assembling at Corinth was, or ought to have been, Halleck's single objective for the time. To overtake

that army and destroy it ought to have been Halleck's first single purpose. "When you have resolved to fight a battle, collect

your whole force." Halleck had the three armies of Grant, Pope, and Buell within the theater; he

ought to have let go all other objectives for the time, and concentrated those three armies for battle with Johnston. Every company left operating against the Confederate posts on the Mississippi

which did not keep an equivalent force of Confederates from joining Johnston's

main body was a company wrongly employed. Pope's army ought to have taken part in the battle of Shiloh.

Nor would the Confederate detachments in those two forward and isolated

posts have had any chance of holding out after the main Confederate army had fallen back to Corinth. As the little force of 7,000 or 8,000 men, however, "contained" more than thrice

their number of the enemy, Pope's army, the sacrifice would have been amply justified if it had resulted in a Confederate

victory at Shiloh.

On the 3d of April, just before the movement on Shiloh, the main body of

Johnston's army was at Corinth, with two bad roads to march

by; one division was at Burnsville, a railway station fifteen miles to the east; another division

was at Bethel, a station twenty miles to the north. These

columns were to converge near Mickey's, a road center about eight miles from Pittsburg Landing. Owing to poor maps, bad roads,

and inexperience and inefficiency on the part of officers and men, the concentration was made so slowly that the attack planned

for daylight of the 5th could not take place until the 6th. This not only lessened the chances of taking the Union army unawares

but also enabled Buell to reach the ground in time to defeat the Confederates on the 7th. This incident illustrates, alike,

the importance of good maps; the importance of carefully reckoning with the elements of time, distance, the condition of the

roads, and the quality of the troops, in combining movements; and the obligation that rests upon every subordinate commander,

from the second in command down to the platoon commanders, to carry out his part of the plan in spite of all hindrances.

By their defeat at Shiloh the Confederates were thrown back upon Corinth,

losing all hold upon Tennessee west of the mountains, except two or three forts on the Mississippi, which were soon wrested

from them; the South experienced the severest blow it had as yet received; the way was opened for Halleck to assemble 100,000

troops, without any interference; and the opportunity was made for him, if he had possessed the will and the ability to avail

himself of it, to crush the remnant of Beauregard's beaten army within a few days, and to "split secession in twain in one

month," as he had promised to do.

So much for the strategy of the campaign. We have not enough space to devote

to the tactics of the engagement. Chapters might easily be spent in pointing out faults and mistakes; but probably no other

great battle of the Civil War furnished fewer examples of good tactics for the student to emulate than the battle of Shiloh, especially the first day's action.

The first and most glaring fault to be noticed is that neither hostile army on that day was commanded

in fact. The two armies fought without heads. To this circumstance all the other errors and shortcomings may properly be charged.

General Grant was not on the field at all until several hours after the engagement began, and neither he nor General Johnston

established headquarters from which to direct or control his forces. Grant "visited" his several division commanders, and

gave them some verbal orders; but the different positions were taken up without any direction from him. Hurlbut and W. H.

L. Wallace had sent forward reinforcements from their respective divisions, as they judged best, and had moved forward to

form their line before General Grant arrived. General Johnston went immediately into the thick of the battle, and "was killed

doing the work of a brigadier." At one time General Johnston, commander in chief; General Breckinridge, Ex-Vice-President

of the United States; and Governor Harris of Tennessee were all three found leading a single regiment forward. General Grant and General Johnston, as army commanders, exerted very little

influence upon the character of the tactics in this great battle.

Johnston

and Beauregard had planned to make their "main attack" against the Union left, with a view

to driving the army back upon Snake Creek and Owl Creek. The onset, however, developed into a simple frontal attack all along

the line. "The front of attack, which was at first less than 2,000 yards in length, in three hours extended from the Tennessee

River, on the east, to Owl Creek, on the west, nearly four miles . . . The attack was turning both flanks, and breaking the

center, all at once-a procedure only to be used by an overwhelming force. The Federals, instead of being driven down the river,

as the intention was, were driven to the landing, where their gunboats and supplies were."

The

Union army, which should have been in a "position in readiness," "was scattered about in isolated camps.... There was no defensive

line, no point of assembly, no proper outposts, no one to give orders in the absence of the regular commander, whose headquarters

were nine miles away. The greenest troops (the divisions of Prentiss and Sherman) were in the most exposed positions. Sherman had three brigades on the right, and one on the left, with an

interval of several miles between them."

"The

Confederate formation shows the mistake of using extended lines instead of deep formations for attack. The long lines, moving

forward, spread out to right and left. Gaps in the forward line were filled by portions of the lines coming up from the Year.

Corps, divisions, and brigades were soon mixed in hopeless confusion. Attacks were made and lost before supporting troops

came up, and the action degenerated into a series of isolated combats, which were without a general plan, and ineffective.

No one knew from whom to take orders. One regiment received orders from three different corps commanders within a short time.

As a result many aimless and conflicting orders were issued which unnecessarily exhausted and discouraged the troops. The

highest commanders, including the adjutant general, went into the fight, and devoted themselves to urging the troops forward,

without any plan or system. By 11: 00 a. m. there was not a reserve on the field. Instead of feeding the fight with their

own troops, the corps commanders finally sought various parts of the field, and took command without regard to the order of

battle. Bragg may be found at the center, at the right, and then the left.... Beauregard remained near Shiloh,

without a reserve, and unable to exercise any influence on the battle."

On

the Federal side the tactics were, if possible, worse. With no prearranged plan, there was want of cohesion and concert of

action between the various units. Regiments were rarely overcome in front, but each one fell back because the regiment on

its right or left had done so, and exposed its flank. Then it continued its backward movement, in turn exposing the flank

of its neighbor, which then must needs, also, fall back. Once in operation this process repeated itself indefinitely. The

reserves were not judiciously used to counteract partial reverses, and to preserve the front of battle.

The

straggling, or rather skulking, on the Confederate side, and the fleeing to the rear on the Union side, were frightful among

the raw troops. On the Union side crowds of terror-stricken fugitives, estimated all the way from 5,000 to 15,000, huddled

under the bluffs at the riverside; at the close of the day Grant had no more than 4,000 men in line. On the Confederate

side it was hardly any better. "The victorious troops had been demoralized by reckless attacks, which were never supported,

and thousands of them immediately gave up the battle to pillage the camps." It is probable that "the debris of the army surging back upon" Beauregard at

Shiloh, two miles in rear, influenced him to order the attack to cease. He has been much blamed for that order; but it is not at all likely that he could

have carried the last position taken by his enemy that evening. Bragg had only got together two brigades for the attack, and

one of them had no ammunition. Furthermore, Nelson's Union division was just arriving, and night was at hand.

In

his own account of the engagement General Beauregard intimates that he was aware that Buell's army was arriving. If such was the case, he made a mistake in remaining on the field that night.

There was no chance for his depleted army after Buell arrived; he ought to have withdrawn it as quickly, and with as little

loss, as possible. All of his stubborn resistance on the second day was a useless sacrifice of life. Nothing was to be gained

by continuing the battle against overwhelming numbers of fresh troops.

The

character of the battlefield, in general thickly covered with forest, was not favorable for the employment of artillery or

cavalry. The artillery, however, in spite of the woods, played an important part in the battle. We find batteries giving strong

help at every point of attack and defense. Guns were lost on both sides; some were taken and retaken. The last stand of the

Federals, on Sunday evening, was made near a line of guns hastily collected. Those guns played a conspicuous part in the last

act of this day of battle. One battery only disgraced itself, the 13th Ohio

battery. When the first Confederate shell fell among them the men deserted their guns and fled incontinently. "The 13th was

blotted out, and on Ohio's roster its place remained a blank

throughout the war."

The

Union cavalry does not appear to have done anything during the battle; on the side of the Confederates Forrest's horsemen

charged a battery, capturing some of its guns; swept through the shattered Union left, cutting off the troops of Prentiss;

and, on the second day, covered the withdrawal of the beaten army, forming the very last line of the rear guard. On the 8th they boldly charged Sherman's

column and put an end to the Union pursuit.

"The

first day at Shiloh shows, better than any other in our history," Major Swift thinks, "the

kind of work performed by a raw army before it has had experience and discipline." Speaking of the throng of scared fugitives

back at the landing, General Grant says: "Most of these men afterwards proved themselves as gallant as any of those who saved

the battle from which they had deserted." That is to say that with training and service they afterward became good soldiers.

| Shiloh Civil War Campaign Map |

|

| Civil War Battle of Shiloh Battlefield Map |

Recommended Reading: Shiloh--In Hell before Night. Description: James McDonough has written a good, readable and concise history of a

battle that the author characterizes as one of the most important of the Civil War, and writes an interesting history of this

decisive 1862 confrontation in the West. He blends first person and newspaper accounts to give the book a good balance between

the general's view and the soldier's view of the battle. Continued below…

Particularly

enlightening is his description of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston, the commander who was killed on the first day

of the battle. McDonough makes a pretty convincing argument that Johnston fell far short of the image that many give him

in contemporary and historical writings. He is usually portrayed as an experienced and decisive commander of men. This book

shows that Johnston was a man of modest war and command experience,

and that he rose to prominence shortly before the Civil War. His actions (or inaction) prior to the meeting at Shiloh -- offering

to let his subordinate Beauregard take command for example -- reveal a man who had difficulty managing the responsibility

fostered on him by his command. The author does a good job of presenting several other historical questions and problems like

Johnston's reputation vs. reality that really add a lot of

interest to the pages.

Recommended

Reading: Shiloh:

The Battle That Changed the Civil War (Simon & Schuster). From Publishers Weekly: The bloodbath at Shiloh,

Tenn. (April 6-7, 1862), brought an end to any remaining innocence in the Civil

War. The combined 23,000 casualties that the two armies inflicted on each other in two days shocked North and South alike.

Ulysses S. Grant kept his head and managed, with reinforcements, to win a hard-fought victory. Continued below…

Confederate

general Albert Sidney Johnston was wounded and bled to death, leaving P.G.T. Beauregard to disengage and retreat with a dispirited

gray-clad army. Daniel (Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee) has crafted a superbly researched volume that will appeal to

both the beginning Civil War reader as well as those already familiar with the course of fighting in the wooded terrain bordering

the Tennessee River.

His impressive research includes the judicious use of contemporary newspapers and extensive collections of unpublished letters

and diaries. He offers a lengthy discussion of the overall strategic situation that preceded the battle, a survey of the generals

and their armies and, within the notes, sharp analyses of the many controversies that Shiloh

has spawned, including assessments of previous scholarship on the battle. This first new book on Shiloh

in a generation concludes with a cogent chapter on the consequences of those two fatal days of conflict.

Recommended

Reading:

Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862. Review: The bloody and decisive two-day battle of Shiloh (April

6-7, 1862) changed the entire course of the American Civil War. The stunning Northern victory thrust Union commander Ulysses

S. Grant into the national spotlight, claimed the life of Confederate commander Albert S. Johnston, and forever buried the

notion that the Civil War would be a short conflict. The conflagration at Shiloh had its roots in the strong Union advance

during the winter of 1861-1862 that resulted in the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee. Continued below…

The offensive

collapsed General Albert S. Johnston advanced line in Kentucky and forced him to withdraw all the way to northern Mississippi. Anxious to attack the enemy, Johnston began

concentrating Southern forces at Corinth, a major railroad center just below the Tennessee border. His bold plan called for his Army of the Mississippi to march north and destroy General Grant's Army of the Tennessee

before it could link up with another Union army on the way to join him. On the morning of April 6, Johnston

boasted to his subordinates, "Tonight we will water our horses in the Tennessee!"

They nearly did so. Johnston's sweeping attack hit the unsuspecting Federal camps at Pittsburg

Landing and routed the enemy from position after position as they fell back toward the Tennessee River.

Johnston's sudden death in the Peach Orchard, however, coupled

with stubborn Federal resistance, widespread confusion, and Grant's dogged determination to hold the field, saved the Union

army from destruction. The arrival of General Don C. Buell's reinforcements that night turned the tide of battle. The next

day, Grant seized the initiative and attacked the Confederates, driving them from the field. Shiloh

was one of the bloodiest battles of the entire war, with nearly 24,000 men killed, wounded, and missing. Edward Cunningham,

a young Ph.D. candidate studying under the legendary T. Harry Williams at Louisiana

State University, researched and wrote Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 in 1966. Although it remained unpublished, many Shiloh

experts and park rangers consider it to be the best overall examination of the battle ever written. Indeed, Shiloh

historiography is just now catching up with Cunningham, who was decades ahead of modern scholarship. Western Civil War historians

Gary D. Joiner and Timothy B. Smith have resurrected Cunningham's beautifully written and deeply researched manuscript from

its undeserved obscurity. Fully edited and richly annotated with updated citations and observations, original maps, and a

complete order of battle and table of losses, Shiloh and the Western Campaign of 1862 will

be welcomed by everyone who enjoys battle history at its finest. Edward Cunningham, Ph.D., studied under T. Harry Williams

at Louisiana State

University. He was the author of The Port Hudson Campaign: 1862-1863

(LSU, 1963). Dr. Cunningham died in 1997. Gary D. Joiner, Ph.D. is the author of One Damn Blunder from Beginning to End: The

Red River Campaign of 1864, winner of the 2004 Albert Castel Award and the 2005 A. M. Pate, Jr., Award, and Through the Howling

Wilderness: The 1864 Red River Campaign and Union Failure in the West. He lives in Shreveport,

Louisiana. About the Author: Timothy B. Smith, Ph.D., is author of Champion Hill:

Decisive Battle for Vicksburg (winner of the 2004 Mississippi

Institute of Arts and Letters Non-fiction Award), The Untold Story of Shiloh: The Battle and the Battlefield, and This Great

Battlefield of Shiloh: History, Memory, and the Establishment of a Civil War National Military Park. A former ranger at Shiloh,

Tim teaches history at the University of Tennessee.

Recommended

Reading: Seeing the Elephant: RAW RECRUITS AT THE BATTLE OF SHILOH. Description: One of the bloodiest battles in the Civil War, the

two-day engagement near Shiloh, Tennessee,

in April 1862 left more than 23,000 casualties. Fighting alongside seasoned veterans were more than 160 newly recruited regiments

and other soldiers who had yet to encounter serious action. In the phrase of the time, these men came to Shiloh

to "see the elephant". Continued below…

Drawing on

the letters, diaries, and other reminiscences of these raw recruits on both sides of the conflict, "Seeing the Elephant" gives

a vivid and valuable primary account of the terrible struggle. From the wide range of voices included in this volume emerges

a nuanced picture of the psychology and motivations of the novice soldiers and the ways in which their attitudes toward the

war were affected by their experiences at Shiloh.

Recommended Reading: The Battle of Shiloh and the Organizations

Engaged (Hardcover). Description: How

can an essential "cornerstone of Shiloh historiography" remain unavailable to the general

public for so long? That's what I kept thinking as I was reading this reprint of the 1913 edition of David W. Reed's “The

Battle of Shiloh and the Organizations Engaged.” Reed, a veteran of the Battle of Shiloh and the first historian of

the Shiloh National

Military Park, was tabbed to

write the official history of the battle, and this book was the result. Reed wrote a short, concise history of the fighting

and included quite a bit of other valuable information in the pages that followed. The large and impressive maps that accompanied

the original text are here converted into digital format and included in a CD located within a flap at the back of the book.

Author and former Shiloh Park Ranger Timothy Smith is responsible for bringing this important reference work back from obscurity.

His introduction to the book also places it in the proper historical framework. Continued below…

Reed's history of the campaign and battle covers only seventeen pages and is meant to be a brief history of the subject.

The detail is revealed in the rest of the book. And what detail there is! Reed's order of battle for Shiloh goes down to the regimental

and battery level. He includes the names of the leaders of each organization where known, including whether or not these men

were killed, wounded, captured, or suffered some other fate. In a touch not often seen in modern studies, the author also

states the original regiment of brigade commanders. In another nice piece of detail following the order of battle, staff officers

for each brigade and higher organization are listed. The book's main point and where it truly shines is in the section entitled

"Detailed Movements of Organizations". Reed follows each unit in their movements during the battle. Reading this section along

with referring to the computerized maps gives one a solid foundation for future study of Shiloh.

Forty-five pages cover the brigades of all three armies present at Shiloh.

Wargamers and buffs will love the "Abstract of Field Returns". This section lists Present for Duty, engaged, and casualties

for each regiment and battery in an easy to read table format. Grant's entire Army of the Tennessee has Present for Duty strengths. Buell's Army of the Ohio is also counted well. The Confederate Army of the Mississippi

is counted less accurately, usually only going down to brigade level and many times relying only on engaged strengths. That

said, buy this book if you are looking for a good reference work for help with your order of battle.

In what I believe is an unprecedented move in Civil War literature, the University

of Tennessee Press made the somewhat unusual decision to include Reed's

detailed maps of the campaign and battle in a CD which is included in a plastic sleeve inside the back cover of the book.

The cost of reproducing the large maps and including them as foldouts or in a pocket in the book must have been prohibitive,

necessitating this interesting use of a CD. The maps were simple to view and came in a PDF format. All you'll need is Adobe

Acrobat Reader, a free program, to view these. It will be interesting to see if other publishers follow suit. Maps are an

integral part of military history, and this solution is far better than deciding to include poor maps or no maps at all. The

Read Me file that came with the CD relays the following information:

-----

The maps contained on this CD are scans of the original oversized maps printed in the 1913 edition of D. W. Reed's The

Battle of Shiloh and the Organizations Engaged. The original maps, which were in a very large format and folded out of the

pages of this edition, are of varying sizes, up to 23 inches by 25 inches. They were originally created in 1901 by the Shiloh National Military Park under the direction of its historian,

David W. Reed. They are the most accurate Shiloh battle maps in existence.

The maps on the CD are saved as PDF (Portable Document Format) files and can be read on any operating system (Windows,

Macintosh, Linux) by utilizing Adobe Acrobat Reader. Visit http://www.adobe.com to download Acrobat Reader if you do not have

it installed on your system.

Map 1. The Field of Operations from Which the Armies Were Concentrated at Shiloh, March

and April 1862

Map 2. The Territory between Corinth, Miss., and Pittsburgh Landing, Tenn., Showing Positions and Route of the Confederate

Army in Its Advance to Shiloh, April 3, 4, 5, & 6, 1862

Map 3. Positions on the First Day, April 6, 1862

Map 4. Positions on the Second Day, April 7, 1862

Complete captions appear on the maps.

-----

Timothy Smith has done students of the Civil War an enormous favor by republishing this important early work on Shiloh. Relied on for generations by Park Rangers and other serious students of the battle, The Battle

of Shiloh and the Organizations Engaged has been resurrected for a new generation of Civil War readers. This classic reference

work is an essential book for those interested in the Battle of Shiloh. Civil War buffs, wargamers, and those interested in

tactical minutiae will also find Reed's work to be a very good buy. Highly recommended.

|