|

Culp's Hill

Battle of Gettysburg

Culp's Hill Battle of Gettysburg, Fish Hook Battle of Gettysburg Rock Creek Summit Spangler's Spring,

General Johnson's Division Ewell's Corps Culp's Hill, General Greene General Henry Slocum Battle of Gettysburg

Culp's Hill and Battle of Gettysburg

Introduction

The summer of 1863 would mark the turning point in the bloodiest period

of American history. Tens of thousands had already perished in the great conflict known as the American Civil War. Hundreds

of thousands more would die by the time it concluded in 1865. After nearly two years of fighting, President Abraham Lincoln

was still casting about for a competent general to lead the North's main force, the Army of the Potomac. That year he settled

on the leadership of Maj. Gen. "Fighting" Joe Hooker who was promptly trounced by Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia

at Chancellorsville, Virginia, in early May of 1863. Lincoln would now

turn to Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, a native of Pennsylvania.

But, Chancellorsville was just the latest in a series of stalemates and

defeats with just an occasional victory suffered by Union forces beginning early on at Manassas. Northern moral was ebbing

and the Union needed a victory, a decisive victory. And despite the many battlefield successes that the South had

amassed, the Union war machine kept cranking out what appeared to be an endless supply of recruits and munitions. Lee too needed a decisive victory, but one on Northern soil that could turn the tide

of war and force President Lincoln to sue for peace. Both sides would get their chance in a small inauspicious town in

southeast Pennsylvania.

Summary

During the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1–3, 1863, Culp's Hill

was a critical part of the Union Army defensive line, the principal feature of the right flank, or "barbed" portion of what

is described as the "fish-hook" line, and it was the scene of fierce fighting during the second and third days of the engagement.

Holding the hill was by itself unimportant because its heavily wooded sides made

it unsuitable for artillery placement, but its loss would have been catastrophic to the Union army. It dominated Cemetery

Hill and the Baltimore Pike, the latter being critical for keeping the Union army supplied and for blocking any Confederate

advance on Baltimore or Washington, D.C. See also Battle of Culp's Hill: A History.

| Culp's Hill, Battle of Gettysburg |

|

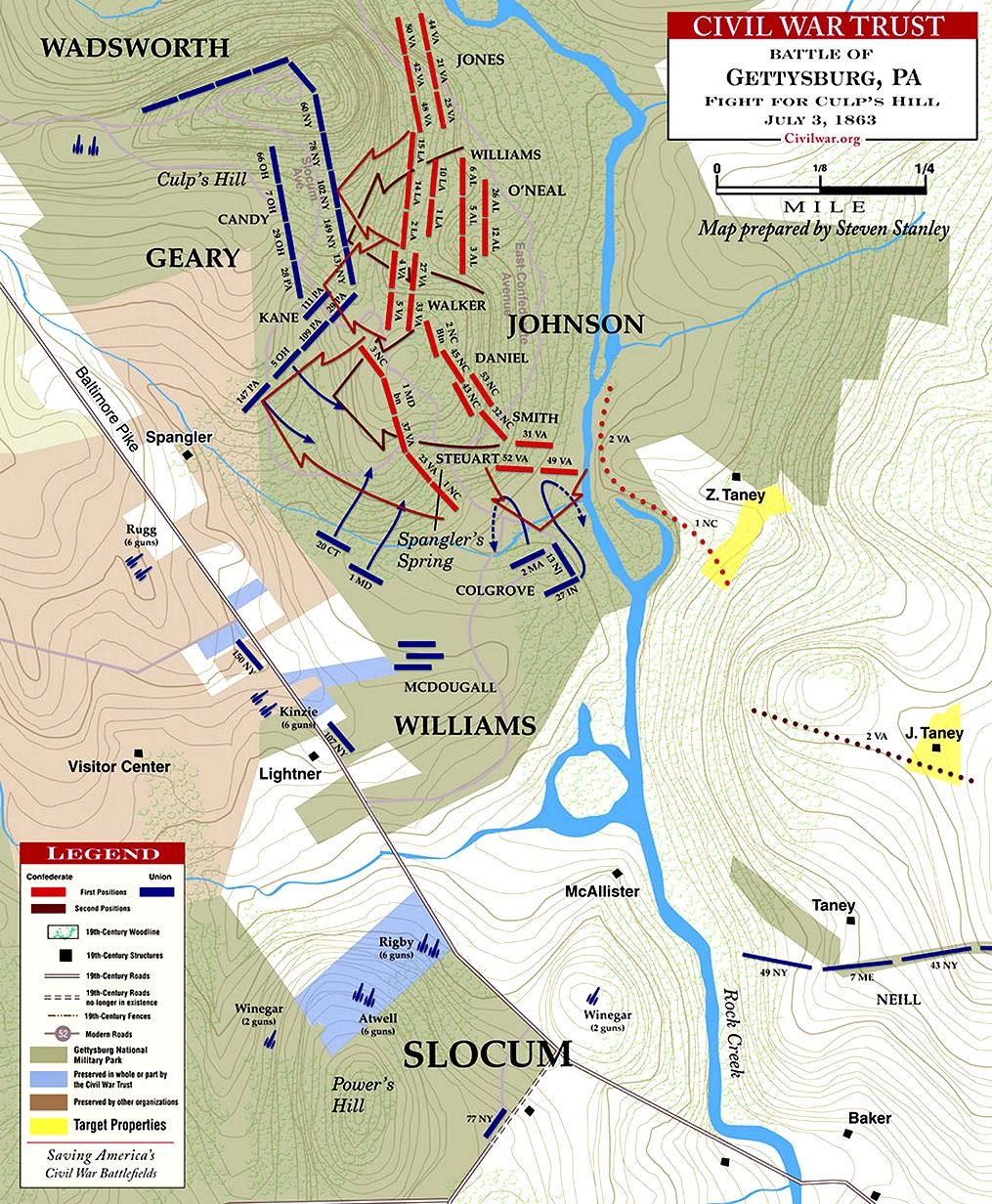

| Fight at Culp's Hill, July 3, 1863 |

| Battle of Culp's Hill |

|

| Battle of Culp's Hill, Gettysbug, July 2-3, 1863 |

Culp's Hill, a landform 3/4 of a mile south of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, played

a prominent role in the Battle of Gettysburg. It consists of two rounded peaks, separated by a narrow saddle. Its heavily

wooded higher peak is 630 feet above sea level. The lower peak is about 100 feet shorter than its companion. The eastern slope

descends to Rock Creek, about 160 feet lower in elevation, and the western slope

is to a saddle with Stevens Knoll (formerly McKnight's Hill) with a summit 100 feet lower than the main Culp's Hill summit.

The hill was owned in 1863 by farmer Henry Culp and was publicized as "Culp's Hill" by October 31, 1865.

The second day of fighting at

the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2nd was the largest and costliest of the three days. The second day's fighting (at Devil’s

Den, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, Cemetery Ridge, Trostle’s Farm, Culp’s Hill and Cemetery

Hill) involved at least 100,000 soldiers of which roughly 20,000 were killed, wounded, captured or missing. The second

day in itself ranks as the 10th bloodiest battle of the Civil War. The third day of fighting consisted of Culp's

Hill, Cemetery Ridge, namely Pickett's Charge, and two cavalry battles: one approximately three miles to the east, known as

East Cavalry Field, and the other southwest of Big Round Top mountain on South Cavalry Field.

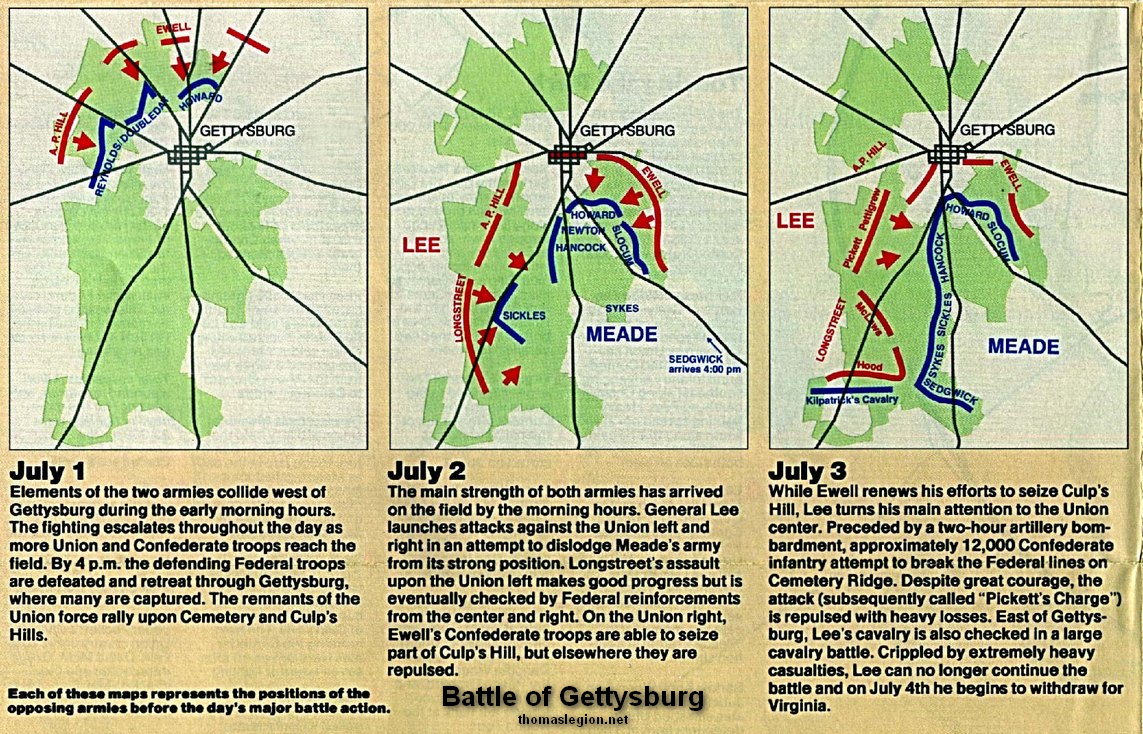

Gen. Robert E. Lee had concentrated his full strength against Maj. Gen.

George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac at the crossroads county seat of Gettysburg at what is now known as the Battle

of Gettysburg. On July 1, Confederate forces converged on the town from west and north, driving Union defenders back through

the streets to Cemetery Hill. During the night, reinforcements arrived for both sides. On July 2, Lee attempted to envelop

the Federals, first striking the Union left flank at the Peach Orchard, Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, and the Round Tops

with Longstreet’s and Hill’s divisions, and then attacking the Union right at Culp’s and East Cemetery Hills

with Ewell’s divisions. By evening, the Federals retained Little Round Top and had repulsed most of Ewell’s men.

During the morning of July 3, the Confederate infantry were driven from their last toe-hold on Culp’s Hill. In the afternoon,

after a preliminary artillery bombardment, Lee attacked the Union center on Cemetery Ridge. The Pickett-Pettigrew assault

(more popularly, Pickett’s Charge) momentarily pierced the Union line but was driven back with severe

casualties. Stuart’s cavalry attempted to gain the Union rear but was repulsed. On July 4, Lee began withdrawing his

weary army toward Williamsport on the Potomac River, thus concluding the Battle of Gettysburg. While the Confederate train

of wounded stretched more than fourteen miles, the dead that now littered the Gettysburg battlefield could scarcely be replaced.

Lee would now refrain from any additional incursions into the Northern states.

| Culp's Hill from Cemetery Hill |

|

| Viewing Culp's Hill from Cemetery Hill |

History

A substantial hill with heavily wooded slopes, Culp's Hill was a perfect anchor for the Union right flank at Gettysburg, and became known as the point of the famous "fishhook". It was first occupied

on the evening of July 1 by Union soldiers of the First Corps who had fought most of that same day west of Gettysburg, and

spent their first hours on the hill felling trees to build a strong line of earthen and log defenses called breastworks. They

were joined the following day by the Twelfth Corps, whose men added to the line of works stretching from the summit of the

hill to Spangler's Spring. The remains of these breastworks still exist today, marking the Union battleline.

Culp's Hill is still thick with tree cover today, though at the time of the battle the woods were not as dense. Farmers cut

down and removed smaller trees and brush, leaving the healthy hardwoods of oak, maple and chestnut to grow large enough for

later harvest as lumber for wagons, furniture, and building material. This open nature of the woods benefited its defenders,

providing them with a clear field of fire and ability to see any enemy approach.

| Gen. Johnson |

|

| Generals in Gray |

| Gen. Greene |

|

| Generals in Blue |

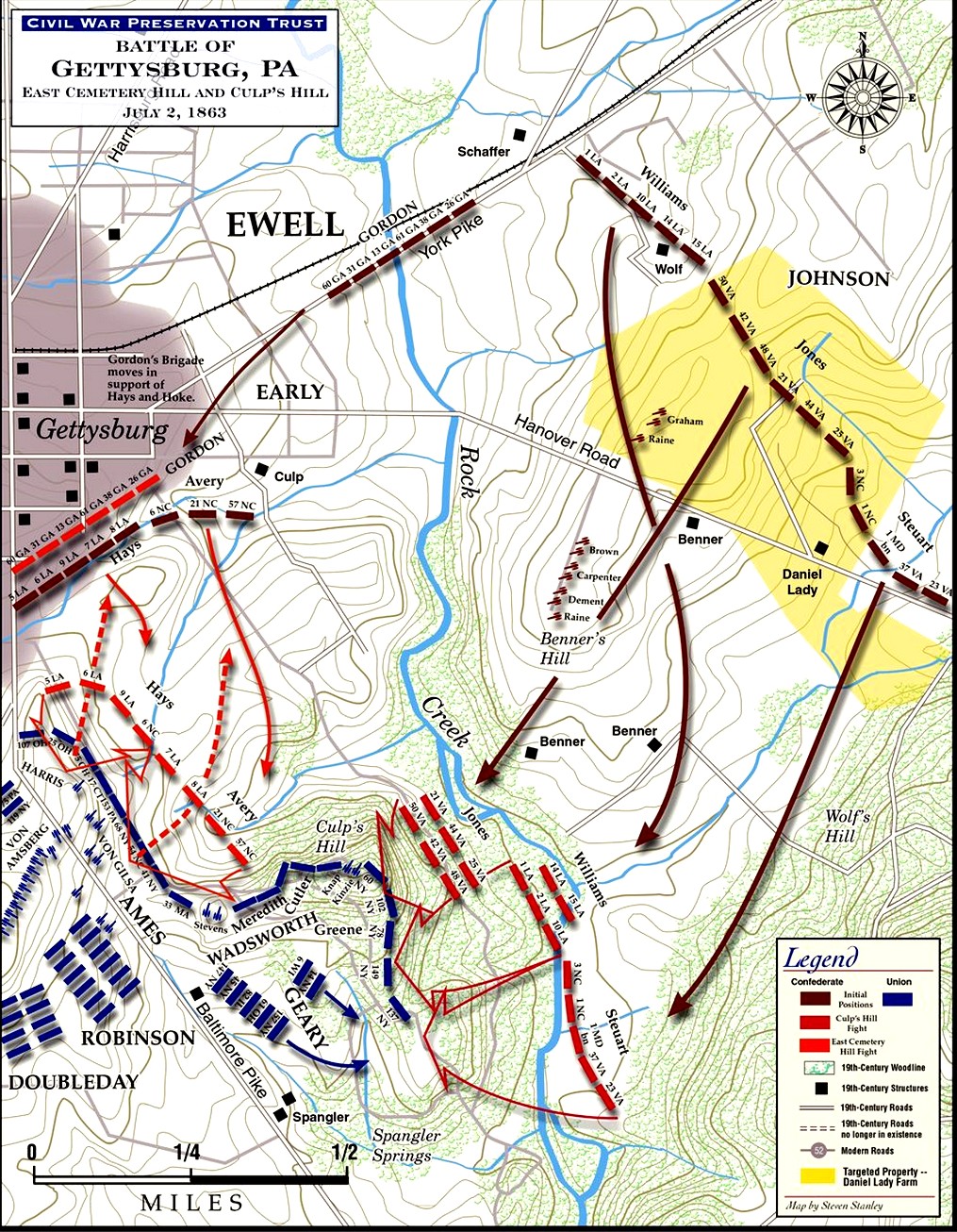

The situation on Culp's Hill remained quiet throughout July 2 until dusk when,

in the gathering darkness, Union troops distinctly heard the tramp of thousands of feet on dry leaves, which grew louder and

closer with the gloom of night. It was Maj. General Edward Johnson's Division from Ewell's Corps finally making their way

down to Rock Creek, which runs at the eastern base of the hill.

(Left) Union Brig. Gen. Greene and (Right) Confederate Maj. Gen. Johnson.

Johnson had been forced to delay his attack that afternoon and it was not

until after 8 P.M. when his men were close enough to make the charge up Culp's Hill, unaware of what they would find once

they reached it. The men waded the creek and reformed their ranks in the dark woods before beginning the final advance.

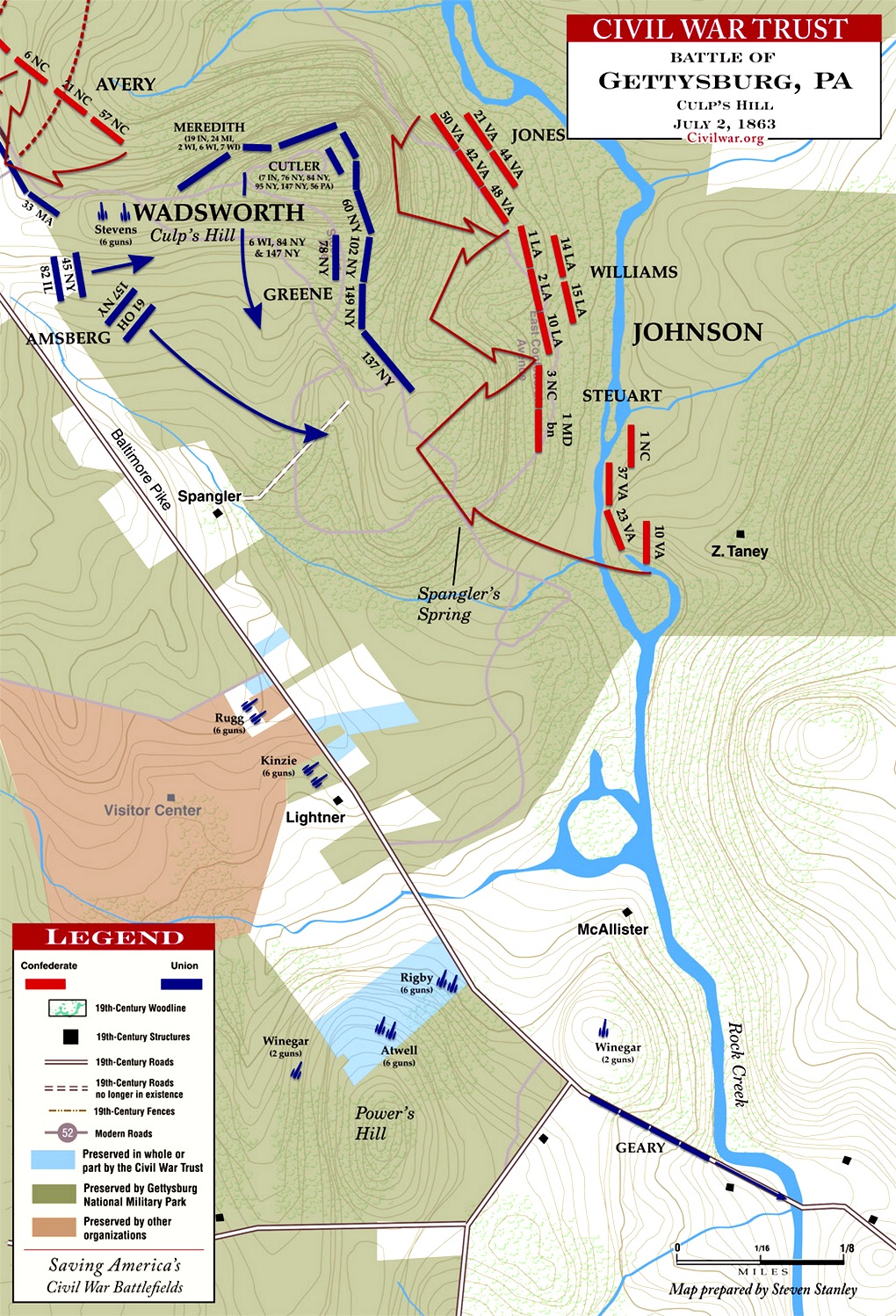

| Culp's Hill Battlefield Map |

|

| Battle of Culp's Hill, July 2, 1863 |

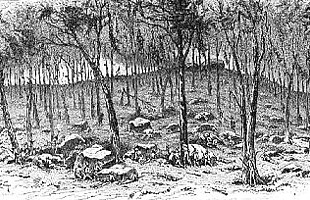

| Confederates storm the summit of Culp's Hill |

|

| Battles and Leaders |

What Johnson did not know was that most of the Twelfth Corps who had manned

the breastworks until the afternoon of July 2, were no longer there. The corps was ordered to reinforce the embattled Union

left, leaving behind a single brigade of New York regiments under Brig. General George Sears Greene to hold the hill. Knowing

that it would be hours before the missing troops would return, the 62 year-old Greene was determined not to give up any of

this valuable ground. He ordered his officers to stretch the line as thin and far as possible to cover the vacant works, and

to hold their positions at all costs.

Greene completed his shifting of troops and not a moment too soon- Johnson's

Confederates splashed across Rock Creek and began to ascend the hill just as the last of his regiments deployed into the breastworks

south of the summit. Greene's men silently waited until the gray formations were within a hundred feet, when they stood and

unleashed a perfect storm of musketry fire into the darkness. "It was a critical period in the history of the battle," reported

General Henry Slocum, commander of the corps. "Although this attack on Greene was made by vastly superior numbers, suddenly

and without warning, under the cover of darkness, the gallant veteran promptly disposed his slender forces to the best advantage

and held his line unbroken throughout the night."

Muzzle flashes lit up the hillside. Greene's New Yorkers blazed away with

a steady stream of fire, moving and shifting from one section of works to another to stem Confederate thrusts. Regiments from

the First and Eleventh Corps arrived to assist Greene and moved into the lower portion of hill, throwing their weight in as

they saw fit, keeping the Confederates off guard. Little could be seen in the darkness and most Southerners took advantage

of cover provided by the multitude of large boulders and trees on the rough hillside.

| Culp's Hill Battlefield Map |

|

| Battle of Culp's Hill Map |

| 29th Pennsylvania Infantry attacks |

|

| 29th Pennsylvania Infantry attacks, July 3, 1863. |

In the end, Greene's tactics worked. In the confusion of the night battle,

Johnson believed that he was facing a much larger force than expected. "The attack was made with great vigor and spirit,"

the general wrote. "It was as successful as could have been expected, considering the superiority of the enemy's force and

position. (Brig. General George) Steuart's Brigade, on the left, carried a line of breastworks which ran perpendicular to

the enemy's main line, captured a number of prisoners and a stand of colors, and the whole line advanced to within short range

and kept up a heavy fire until late in the night."

The firing died away near midnight, replaced by the dreadful groans of wounded

soldiers lying on the hillside. Clear objectives could not be determined in the darkness and with the belief that he was heavily

outnumbered, Johnson decided to wait until first light to renew his attack at which time he would have the necessary reinforcements.

(Right) 29th Pennsylvania Infantry attacks, July 3, 1863. Battles & Leaders.

Returning to Culp's Hill after midnight, troops of the Twelfth Corps deployed astride the Baltimore Pike and

prepared to retake the Confederate-held positions, also at first light. Union guns stationed near the Baltimore Pike opened

a furious bombardment at 4 A.M., quickly followed by the advance of line upon line of Union regiments that swept into the

woods. Johnson's men fought back furiously, grimly holding their positions without the benefit of any Southern artillery.

The fighting continued for several hours and gun smoke hung thick under the tree cover. Soldiers hid behind rocks and trees,

firing at shadows in the gloomy woods that echoed with the cries of combatants and wounded men, fearful that no one could

get to them because of the intense rifle fire. "The enemy had been re-enforced during the night," General Slocum reported

after the battle, "and were fully prepared to resist our attack. The force opposed to us... under General Ewell, formerly

under General (Stonewall) Jackson,... fought with a determination and valor which has ever characterized the troops of this

well known corps."

| East Cemetery and Culp's Hill Battlefield Map |

|

| Battle of East Cemetery and Culp's Hill, July 3, 1863 |

| Culp's Hill |

|

| Culp's Hill. Gettysburg NMP. |

|

| Wesley Culp |

Commanders shifted troops into positions up and down the hill so that a

constant fire could be maintained against the Confederates, the bullets slamming into trees and men alike. Around the summit

of Culp's Hill, Greene's New Yorkers faced Louisiana soldiers of General Nicholls' Brigade. The fighting had reached a fever

pitch with the Southerners having made their way up to the summit before halting a mere thirty feet from the Union works.

In a bold move to clear the front of the Union line, the 66th Ohio Infantry moved out of the works and swept the front of

the hill, driving out a number of Confederate skirmishers who had crept within twenty paces of the Union position. The bold

sweep worked, driving back the exhausted Confederates. "We tried again and again to drive the enemy from their position,"

reported Lt. Colonel L.H. Salyer of the 50th Virginia Infantry, "but at length we were compelled to fall back, worn down and

exhausted. At one time we were within a few feet of their works, but the fire was so

heavy we could not stand it."

By 10 o'clock that morning, the Union counterattack had succeeded and the

hill was securely in Union hands. The battle for Culp's Hill ended as Johnson's exhausted soldiers retreated across Rock Creek,

leaving the woods filled with dead and wounded.

Among the dead was a young soldier who had grown up in Gettysburg

and spent much of his youth exploring his uncle's hill. As a young man he learned the trade of harness making and when his

employer moved to Shepherdstown, Virginia, he bade his hometown goodbye and moved to the small town across the Potomac River.

Having adopted his Southern home as his own and acquiring the Southern spirit, Culp enlisted in the Confederate army at the

outbreak of the Civil War and served in the 2nd Virginia Infantry of the famous "Stonewall Brigade".

| Culp's Hill |

|

| Breastworks at Culp's Hill |

(Left) This picture was photographed soon after the battle of Gettysburg,

and these breastworks at Culp's Hill were constructed by soldiers of the Iron Brigade. Library of Congress.

Little could he have known that one day he would be fighting on his uncle's

farm in Adams County. Sometime during the battle on July 3, Private Culp was killed. Comrades buried him near the hill and

marked his grave. After the battle a shattered remnant of his rifle was found, a portion of the wooden rifle stock with his

name carved in it. What happened to Wesley Culp's remains are a mystery, though it was rumored that family members located

the grave and secreted his body to the family plot in Evergreen Cemetery.

While the battle raged around the summit of Culp's Hill, there was also severe

fighting at the southern end near Spangler's Spring.

Both sides regrouped and prepared for what would soon become some of the bloodiest fighting of the war. Midday, the

Confederates began an intense artillery barrage in the direction of Cemetery Ridge. Union artillery along the ridge replied

in kind and then abruptly ceased fire to conserve ammunition, which caused the Confederates to believe that they had destroyed

the Union guns. During this pause, or lull, Federal units began arriving and reinforcing the line directly to the front

of the Southern troops who were forming for an imminent advance.

At 3 p.m., nine Confederate Brigades under the command of Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett began their suicidal

march over open terrain towards the reinforced Union line a mile away. On a field rich with targets, the Union artillerists opened

up methodically mowing down thousands of advancing Confederates in what would be termed Pickett's Charge. Those who

did escape the barrage would continue their advance and crash headlong into heavy Union musketry that was in

well protected defensive positions. As Federal cannons continued to rake the advancing Rebels, coordinated

infantry unleashed devastating volleys into waves of gray. In what must have been Lee's worst hour,

the General rode out to meet his soldiers lamenting that "it was all my fault." The next day the Confederates withdrew from

Gettysburg and marched back towards Virginia.

| Culp's Hill Battlefield Map |

|

| Battle of Culp's Hill, July 3, 1863 |

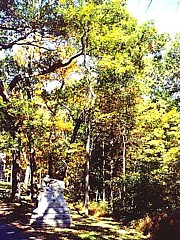

Preservation of Battlefield Resources at Gettysburg National Military Park

Silent sentinels of the violence that raged there, the trees on Culp's Hill bore visible scars of the battle

for many years afterward and were a battlefield curiosity for early visitors. Though all of these original trees are gone,

there are still physical reminders of the battle in existence at Culp's Hill- the remains of breastworks constructed by Union

troops, scars on the landscape that mark the Union line of battle of July 1-3, 1863. They are more than mere bumps on the

hillside- they are surviving relics of the battle.

| Culp's Hill |

|

| Culp's Hill Earthworks |

(Right) Traces of Union

breastworks still survive on Culp's Hill, stretching from its summit to the knoll above Spangler's Spring. Photo Gettysburg

NMP.

Preservation of these earthworks for future generations has always been a

problem. The first park commission (1895-1933) planted grass seed on the earthwork remains to help protect them and placed

small signs asking visitors to keep off the mounds. Yet, natural erosion, uncontrolled tree growth, vehicles and foot traffic

from 1.8 million visitors per year have worn down the remains of these structures. Slowly they are melting away and without

preservation efforts taking place now, they may all be gone in the not so distant future.

The National Park Service has undertaken a plan to preserve these important

battlefield resources by using the natural cover of grass and sod to save the works from further deterioration. Large trees

and shrubs, whose roots undermine the earthwork remains, have been trimmed back by volunteers. Some of the erosion damage

has been repaired with rock and new topsoil. Stone barricades have been restacked and the trenches of the earthworks have

been cleaned of bottles and trash that had accumulated in them over the past 60 years. Visitors to Culp's Hill and the other

park sites that have the remains of trenches, earthworks, stonewalls, and gun lunettes can also help by staying on designated

paths and refraining from walking in the trenches or on the earthworks. Every effort made by a visitor today will help preserve

these important features for the visitors of tomorrow.

Sources: Gettysburg National Military Park; National Archives; Official

Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Library of Congress; Civil War Trust, civilwar.org.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg--Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill (Civil War America) (Hardcover). Description: In this companion to his celebrated earlier book, Gettysburg—The

Second Day, Harry Pfanz provides the first definitive account of the fighting between the Army of the Potomac and Robert E.

Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill—two of the most critical engagements fought at Gettysburg on 2 and 3 July 1863. Pfanz provides detailed tactical accounts

of each stage of the contest and explores the interactions between—and decisions made by—generals on both sides.

In particular, he illuminates Confederate lieutenant general Richard S. Ewell's controversial decision not to attack Cemetery

Hill after the initial southern victory on 1 July. Continued below...

Recommended Reading: Culp's

Hill: The Attack And Defense Of The Union Flank, July 2, 1863 (Battleground America). Description: South of the town of Gettysburg, Union troops take possession of the wooded heights at the tip of their "fishhook" defensive line. Defending Culp's Hill meant protecting the flank; it was the key

to victory. Using official reports, letters, diaries, and memoirs, this book describes the struggle for the high ground and

tells how and why the generals made their crucial decisions. "Cox tells this dramatic story with great skill...Excellent narrative

and analysis...Concisely written and informative." Continued below…

About the Author: John

D. Cox is a lifelong student of Gettysburg and a Licensed Battlefield Guide at Gettysburg

National Park. A veteran of the U.S. Air Force, he now spends his days

speaking at Civil War roundtables and giving tours at Gettysburg.

Recommended

Reading: The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command (928 pages).

Description: Coddington's research is one of the most thorough and detailed studies

of the Gettysburg Campaign. Exhaustive in scope and scale, Coddington delivers, with unrivaled research, in-depth battle descriptions

and a complete history of the regiments involved. This is a must read for anyone

seriously interested in American history and what transpired and shaped a nation on those pivotal days in July 1863.

Recommended Reading: Gettysburg,

by Stephen W. Sears (640 pages) (November 3, 2004). Description: Sears delivers another masterpiece with this comprehensive study of America’s most studied Civil War battle. Beginning with Lee's meeting with

Davis in May 1863, where he argued in favor of marching north, to take pressure off both Vicksburg and Confederate logistics. It ends with the battered Army

of Northern Virginia re-crossing the Potomac just two months later and with Meade unwilling

to drive his equally battered Army of the Potomac into a desperate pursuit. In between is

the balanced, clear and detailed story of how tens-of-thousands of men became casualties, and how Confederate independence

on that battlefield was put forever out of reach. The author is fair and balanced. Continued below...

He discusses

the shortcomings of Dan Sickles, who advanced against orders on the second day; Oliver Howard, whose Corps broke and was routed

on the first day; and Richard Ewell, who decided not to take Culp's Hill on the first night, when that might have been decisive.

Sears also makes a strong argument that Lee was not fully in control of his army on the march or in the battle, a view conceived

in his gripping narrative of Pickett's Charge, which makes many aspects of that nightmare much clearer than previous studies.

A must have for the Civil War buff and anyone remotely interested in American history.

Recommended

Reading:

Gettysburg: A Testing of Courage. Description: America's Civil War raged for more than four years, but it is the three days of fighting

in the Pennsylvania countryside in July 1863 that continues

to fascinate, appall, and inspire new generations with its unparalleled saga of sacrifice and courage. From Chancellorsville,

where General Robert E. Lee launched his high-risk campaign into the North, to the Confederates' last daring and ultimately-doomed

act, forever known as Pickett's Charge, the battle of Gettysburg gave the Union army a victory that turned back the boldest

and perhaps greatest chance for a Southern nation. Continued below...

Now, acclaimed

historian Noah Andre Trudeau brings the most up-to-date research available to a brilliant, sweeping, and comprehensive history

of the battle of Gettysburg that sheds fresh light on virtually every aspect of it. Deftly balancing his own

narrative style with revealing firsthand accounts, Trudeau brings this engrossing human tale to life as never before.

Recommended

Reading: General Lee's

Army: From Victory to Collapse. Review: You cannot say that University of North Carolina

professor Glatthaar (Partners in Command) did not do his homework in this massive examination of the Civil

War–era lives of the men in Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Glatthaar spent nearly 20 years examining and

ordering primary source material to ferret out why Lee's men fought, how they lived during the war, how they came close to

winning, and why they lost. Glatthaar marshals convincing evidence to challenge the often-expressed notion that the war in

the South was a rich man's war and a poor man's fight and that support for slavery was concentrated among the Southern upper

class. Continued

below...

Lee's army

included the rich, poor and middle-class, according to the author, who contends that there was broad support for the war in

all economic strata of Confederate society. He also challenges the myth that because Union forces outnumbered and materially

outmatched the Confederates, the rebel cause was lost, and articulates Lee and his army's acumen and achievements in the face

of this overwhelming opposition. This well-written work provides much food for thought for all Civil War buffs.

Recommended

Reading:

The History Buff's Guide to Gettysburg (Key People, Places, and Events) (Key People, Places, and Events).

Description: While most history books are dry monologues

of people, places, events and dates, The History Buff's Guide is ingeniously written

and full of not only first-person accounts but crafty prose. For example, in introducing the major commanders, the authors

basically call Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell a chicken literally. Continued below...

'Bald, bug-eyed, beak-nosed Dick Stoddard Ewell had all the aesthetic charm of a flightless foul.' To

balance things back out a few pages later, they say federal Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade looked like a 'brooding gargoyle

with an intense cold stare, an image in perfect step with his nature.' Although it's called a guide to Gettysburg, in my opinion, it's an authoritative guide to

the Civil War. Any history buff or Civil War enthusiast or even that casual reader should pick it up.

Recommended

Reading: The Maps of Gettysburg:

The Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 - July 13, 1863

(Hardcover). Description: More academic and photographic

accounts on the battle of Gettysburg exist than for all other

battles of the Civil War combined-and for good reason. The three-days of maneuver, attack, and counterattack consisted of

literally scores of encounters, from corps-size actions to small unit engagements. Despite all its coverage, Gettysburg remains one of the most complex and difficult to understand battles of the war.

Author Bradley Gottfried offers a unique approach to the study of this multifaceted engagement. Continued below...

The Maps of

Gettysburg plows new ground in the study of the campaign by breaking down the entire campaign in 140 detailed original maps.

These cartographic originals bore down to the regimental level, and offer Civil Warriors a unique and fascinating approach

to studying the always climactic battle of the war. The Maps of Gettysburg offers thirty "action-sections" comprising the

entire campaign. These include the march to and from the battlefield, and virtually every significant event in between. Gottfried's

original maps further enrich each "action-section." Keyed to each piece of cartography is detailed text that includes hundreds

of soldiers' quotes that make the Gettysburg story come alive. This presentation allows readers to easily

and quickly find a map and text on virtually any portion of the campaign, from the great cavalry clash at Brandy Station on

June 9, to the last Confederate withdrawal of troops across the Potomac River on July 15,

1863. Serious students of the battle will appreciate the extensive and authoritative endnotes. They will also want to bring

the book along on their trips to the battlefield… Perfect for the easy chair or for stomping the hallowed ground of

Gettysburg, The Maps of Gettysburg promises to be a seminal

work that belongs on the bookshelf of every serious and casual student of the battle.

|