|

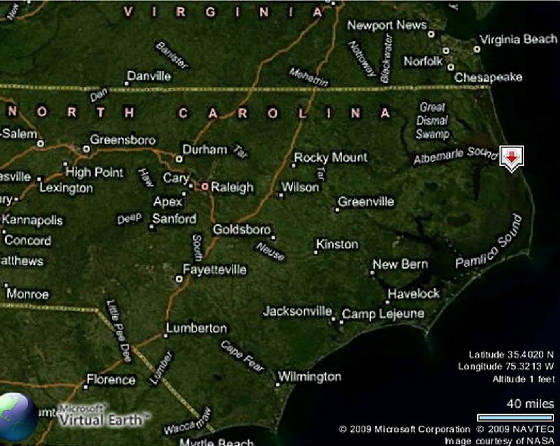

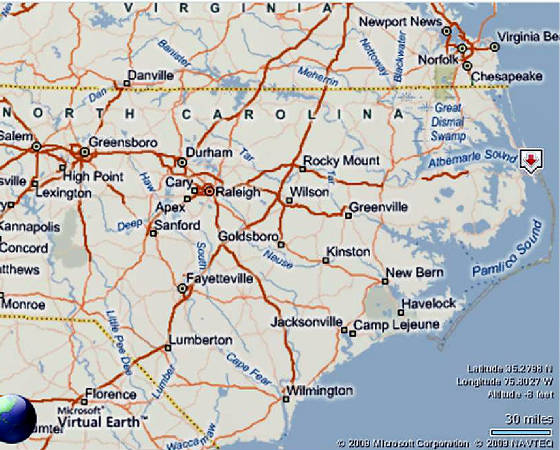

Roanoke Island and the Civil War

Battle of Roanoke Island, North Carolina

Battle of Roanoke

Island

Other Names: Fort Huger

Location: Dare County

Campaign: Burnside's North Carolina Expedition (February-June 1862)

Date(s): February 7-8, 1862

Principal Commanders: Brig. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside [US]; Brig.

Gen. Henry Wise [CS]

Forces Engaged: 10,500 total (US 7,500; CS 3,000)

Estimated Casualties: 2,907 total (US 37K/214W/13M; CS 23K/58W/62M/2,500

Captured)

Result(s): Union victory

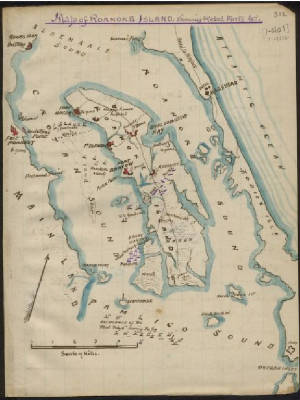

| Civil War Battle of Roanoke Island, NC, Map |

|

| Courtesy Microsoft MapPoint |

Description: On 7 February, Brig. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside landed

7,500 men on the southwestern side of Roanoke Island in an amphibious operation launched from Fort Monroe. The next morning,

supported by gunboats, the Federals assaulted the Confederate forts (see Burnside's North Carolina Expedition) on the narrow waist of the island, driving back and out-maneuvering Brig.

Gen. Henry Wise’s outnumbered command. After losing less than 100

men, the Confederate commander on the field, Col. H. M. Shaw, surrendered about 2,500 soldiers and 32 guns. Burnside had secured

an important outpost on the Atlantic Coast, tightening the blockade. Roanoke Island also was a strategic objective

in Gen. Winfield Scott's Anaconda Plan.

By late spring 1862, Union soldiers occupied Hatteras Inlet and controlled the towns of Plymouth, Washington and New Bern. The loss of most of the North Carolina coast and coastal waterways was

a blow both to Confederate morale and the young nation's ability to supply its armies in the field. But aside from a

few raids from those bases, the Union forces didn't advance until Sherman entered North Carolina in March-April 1865, in what

is commonly referred to as Sherman's March. The following is a history of the battle with maps.

|

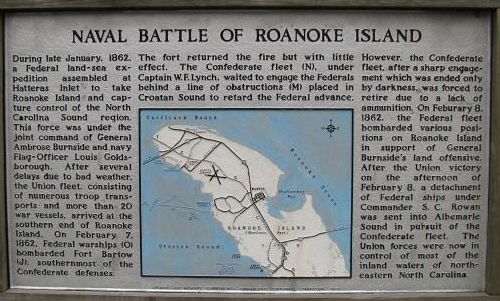

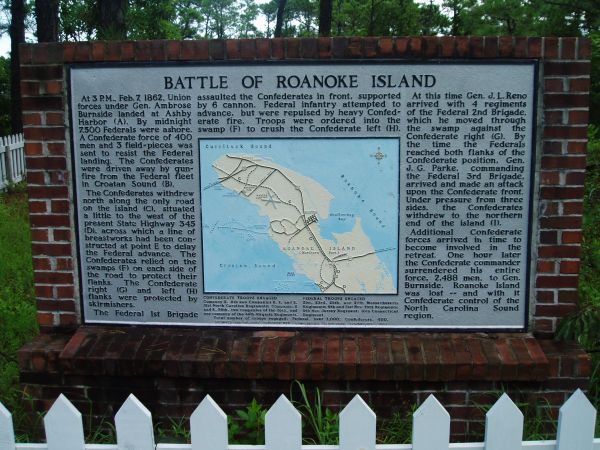

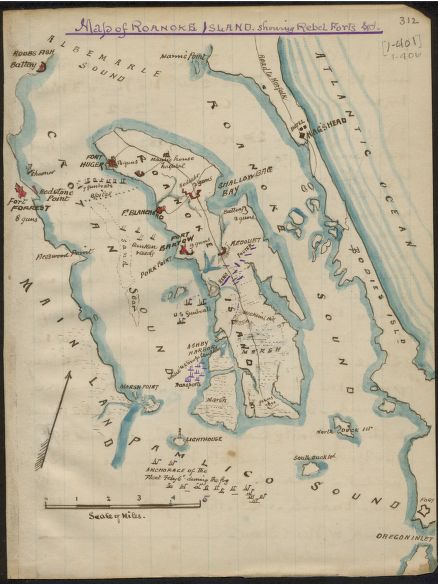

| Confederate forts on Roanoke Island |

| Battle of Roanoke Island |

|

| North Carolina Civil War History |

History: The

opening phase of what came to be known as the Burnside Expedition, the Battle of Roanoke Island was an amphibious operation of the

American Civil War, fought on 7–8 February 1862 in the North Carolina Sounds a short distance south of the Virginia border. The

attacking force consisted of a flotilla of gunboats of the United States Navy drawn from the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron,

commanded by Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, a separate group of gunboats under United States Army control, and an Army

division led by Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside. The defenders were a group of gunboats from the Confederate States

Navy, termed the Mosquito Fleet, under Captain William F. Lynch, and about 2000 Confederate soldiers commanded locally by

Brigadier General Henry A. Wise. The defense was augmented by four forts facing on the water approaches to the island, and

two outlying batteries. At the time of the battle, Wise was hospitalized, so leadership fell to his second in command, Colonel H. M. Shaw.

The first day of the battle

was spent mostly in a gun duel between the Federal gunboats and the forts on shore,

with occasional contributions from the Mosquito Fleet. Rather late in the day, Burnside's soldiers came ashore unopposed; they were accompanied by six howitzers manned

by sailors. As it was too late to fight, the invaders went into camp for the night.

On the second day, 8 February, the Union soldiers advanced, but

were stopped by an artillery battery and accompanying infantry in the center of the island. Although the Rebels thought that

their line was safely anchored in impenetrable swamps, they were flanked on both sides and their soldiers were driven back

to refuge in the forts. The forts were taken in reverse, however. With no way for his men to escape, Col. Shaw surrendered

in order to avoid pointless bloodshed.

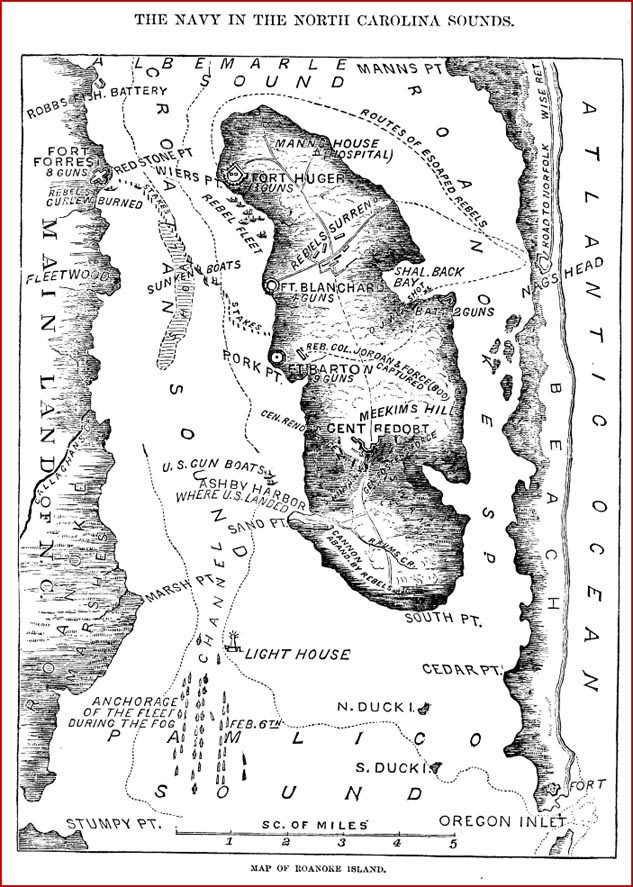

| Civil War Map of Roanoke Island, North Carolina |

|

| Civil War in the N.C. Sounds |

(About) Map shows both Union and

Confederate navies maneuvering for respective positions for the imminent Battle of Roanoke Island.

Strategic Significance:

Northeastern North Carolina is

dominated by its sounds, large but shallow bodies of brackish-to-salt water that lie between the mainland and the Outer Banks. Although they are actually all one body, intimately connected and having

a common level, they are conceptually divided into several distinct regions. The largest of these is Pamlico Sound, immediately behind Hatteras Island; to its north is the second largest, Albemarle Sound, which extends almost to the southern border of Virginia. The linkage between these two, already somewhat narrow,

is further constricted by Roanoke Island. The portion of the waterway between Roanoke Island and the mainland is known as Croatan Sound. Both the island and the sound are about ten

miles (16 km) long. The sound at its widest point is a little more than 4 miles (6.5 km) across, the island about half that.

On the eastern side of the island is Roanoke Sound, much narrower, shallower, and less important.

Several North

Carolina cities were sited on the sounds, among them being New Bern (usually written

New Berne in the mid-nineteenth century), Beaufort, Edenton, and Elizabeth

City. Others, not lying directly on the sounds, were accessible to the

rivers that emptied into them. As much as a third of the state is in their watershed. Through most of the first year of the

Civil War, the sounds remained in possession of Confederate forces, so that coastwise water-borne commerce of the eastern

part of the state was unimpeded. Furthermore, the sounds were linked to Norfolk, Virginia by the Albemarle and Chesapeake

Canal and the Dismal Swamp Canal. This was particularly significant, as it meant that the blockade of Norfolk

could not be complete so long as cargos could reach the city through its back door. Communications were not affected appreciably

when Federal forces captured the forts on the Outer Banks at Hatteras Inlet in August 1861, as the Union Navy could not bring

its deep-water vessels into the sounds through the shallow inlets.

Roanoke

Island was obviously the key to control of the Sounds. If it were controlled by the Union forces, they would have

a base that could be attacked only by an amphibious operation that the Rebels were incapable of. If Union

naval superiority could be established there, all points on the mainland shores would be equally vulnerable to assault. The

Confederate defenders would be forced into an impossible situation: they would either have to give up some positions without

a fight, or they would have to spread their assets too thin to be of any use.

| The Civil War Burnside Expedition Map |

|

| The Civil War Map of Burnside's North Carolina Expedition |

(About) Map reflects Burnside's initial route and thrust to Roanoke

Island, which was the first of a series of battles in the Burnside Expedition. Courtesy Clark's North Carolina Regiments.

| Roanoke Island Civil War Map |

|

| Battle of Roanoke Island |

Preparations

Confederate Defense

The defense of Roanoke Island started in an accidental manner. When the Federal fleet appeared off Hatteras Inlet on 27 August 1861, the 3rd Georgia Infantry Regiment was hastily sent from Norfolk

to help hold the forts there, but the forts fell before they arrived, so they were diverted

to Roanoke Island. They remained there for the next three months, making somewhat desultory

efforts to expel the Yankees from Hatteras Island.

(Right) Union and Confederate warships in lines of battle at Roanoke

Island.

Little was done to secure

the position until early October, when Brigadier General Daniel H. Hill was assigned to command the coastal defenses of North Carolina in the vicinity of the sounds. Hill set his soldiers

to putting up earthworks across the center of the island, but he was called away to service in Virginia before they were completed. Shortly after his departure, his district was split

in two; the southern part was assigned to Brigadier General Lawrence O'B. Branch, while the northern part was put in control

of Brigadier General Henry A. Wise. Wise's command included Albemarle Sound and Roanoke Island, but not Pamlico

Sound and its cities. It is also significant that Branch reported to Brigadier General Richard C. Gatlin, who

commanded the Department of North Carolina, while Wise was under Major General Benjamin Huger, who was in charge of the defenses

of Norfolk.

Wise had been commander

of the so-called Wise Legion, but his troops did not accompany him. The Legion was broken up, although he was able to retain

two of his old regiments, the 46th and 59th Virginia. He also had three regiments of North Carolina

troops, the 2nd, 8th, and 17th North Carolina, plus three companies of the 17th North Carolina. The men from North

Carolina were ill-equipped and ill-clad, often armed with nothing more than their own shotguns. All

told, the number came to about 1400 infantrymen, but the number available for duty was smaller than that because the living

conditions put as many as one-fourth of the command on the sick list.

| Roanoke Island Battlefield Map |

|

| Map of Union and Confederate Navies |

| Battlefield of Roanoke Island Map |

|

| Roanoke Island Civil War Battlefield |

Wise begged Richmond to send him some guns, as had Hill before him, but the

numbers were inadequate. They were distributed into several nominal forts: facing Croatan Sound were twelve guns in Fort Huger,

at Weir's Point, the northwestern corner of the island; four guns in Fort Blanchard, about a mile (1.6 km) to the southeast;

and nine guns in Fort Bartow, at the romantically-named Pork Point, about a quarter of the way down the island. Across the

sound, at Redstone Point opposite Fort Huger,

two old canal barges had been pushed up onto the mud, protected by sandbags and cotton bales, armed with seven guns, and titled FortForrest. These

were all the guns that would bear on the sound; the entire half of the island nearest Pamlico Sound,

the direction from which the attack would come, was unprotected. Five other guns did not face Croatan Sound: a battery of

two guns on the eastern side of the island protected against possible assault across Roanoke Sound, and three others occupied

an earthwork near the geometric center of the island.

Wise made one other contribution

to the defense. He found some pile drivers, and was able to impede the sound between Forts Huger and Forrest by a double row

of piles, augmented by sunken hulks. The barrier was still being worked on when the attack came. The Confederate Navy also made a contribution to the defense. Seven gunboats, mounting a total

of only eight guns, formed the Mosquito Fleet, commanded by Flag Officer William F. Lynch. Wise, for one, believed that their

net contribution was negative. Not only were their guns taken from the forts on the island, but so were their crews. He gave

vent to his feelings after the battle:

"Captain Lynch was energetic,

zealous, and active, but he gave too much consequence entirely to his fleet of gunboats, which hindered transportation of

piles, lumber, forage, supplies of all kinds, and of troops, by taking away the steam-tugs and converting them into perfectly

imbecile gunboats."

Despite Wise's disapproval,

the Mosquito Fleet was part of the defense, and the Yankees would have to deal with it.

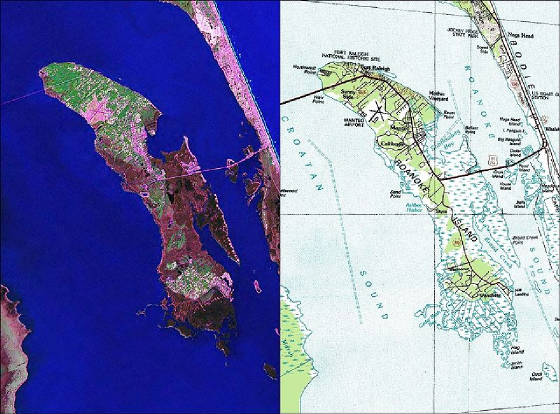

| Satellite Photograph of Roanoke Island, N.C. |

|

| Map of Roanoke Island, North Carolina |

| Roanoke Island Battlefield Map |

|

| Civil War on Roanoke Island |

Union Offense

A short time after Hatteras

Island was captured for the Union, Brigadier General Ambrose E. Burnside began to promote the idea of a Coast Division, to be composed

of fishermen, dockworkers, and other watermen from the northeastern states, and used to attack coastal areas. He reasoned

that such men were already familiar with ships, and therefore would be easy to train for amphibious operations. Burnside was

a close friend of General-in-Chief George B. McClellan, so he got a respectful hearing. Although Burnside had initially intended

to operate in Chesapeake Bay, in the hands of McClellan and the War Department his ideas were soon transformed into a planned

assault on the North Carolina interior coast, beginning with Roanoke

Island. An unspoken reason for the change of target was the mistaken belief that pro-Union sentiment was being

suppressed in North Carolina, and an invasion would allow

the Tar Heels to express their true loyalties. When it was fleshed out, the invasion of North Carolina came to be known as

the Burnside Expedition.

As recruiting progressed,

Burnside organized the Coast Division into three brigades, led by three of Burnside's friends from his Military Academy days. Brig. Gen. John G. Foster

led the First Brigade, Brig. Gen. Jesse L. Reno the Second, and Brig. Gen. John G. Parke the Third. In early January, nearly

13,000 men were ready for duty.

Although the Navy would

provide most of the gunnery that would be needed to suppress the Rebel batteries, Burnside decided to have some gunboats under

Army control. This immediately led to some interference between the two services. The Navy had no vessels sturdy enough to

go to sea and at the same time draw little enough water to be able to pass through the shallow inlet, thought to be about

8 feet (2.5 m). They therefore had to buy suitable merchant ships for conversion, at the very time that Burnside and his agents

were also dickering for their ships. Because the sailors were more experienced, they were able to get most of the more suitable

ships. The Army was left with a mixed bag of rickety ships that were barely seaworthy. By the time the expedition got under

way, the Navy had 20 gunboats, and the Coast Division had 9. The armada was supplemented by several canal boats converted

into floating batteries, mounting boat howitzers and protected by sandbags and bales of hay. All told, the expedition carried

108 pieces of ordnance.

While Burnside's agents

were purchasing the gunboats they were also buying or leasing other vessels to be used as transports. The soldiers and transports

for the expedition assembled at Annapolis. Embarkation began

on 5 January 1862, and on 9 January they began to get under way, with orders to rendezvous at Fort

Monroe, near the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. There

they met the naval contingent, and on 11 January they set sail. Until this time, only Burnside and his immediate staff knew

their ultimate destination. Once at sea, the captain of each ship opened his sealed orders and learned that his ship should

proceed to the vicinity of Cape Hatteras.

| Battle of Roanoke Island, North Carolina |

|

| NC Civil War History |

| Civil War Roanoke Island Battle Map |

|

| Roanoke Island |

From Chesapeake

Bay to Pamlico Sound

For many of the Federal soldiers,

the voyage to Hatteras Inlet was the worst part of the battle. Earning its reputation, the weather in the vicinity of Cape Hatteras turned

foul, causing many of them to become seasick. In an act of bravado, Burnside left his comfortable quarters aboard the transport

George Peabody and with his staff went aboard Army gunboat Picket. He chose this vessel because he considered her to be the

least seaworthy ship in his command, and by showing his troops that he was willing to share their misery, he earned their

devotion. When the storm struck, he began to doubt the wisdom of his move, but Picket survived and got him safely to his destination.

Three vessels in the armada were not so lucky: City of New York,

laden with ordnance and supplies; Pocahontas, carrying horses; and Army gunboat Zouave were all lost, although all persons

aboard were rescued. The only personnel losses were two officers of the Ninth New Jersey, who were drowned when their surfboat

overturned following a visit to the flagship.

The entry into Pamlico Sound through Hatteras Inlet was time consuming. The swash, thought to be eight feet (2.5m)

deep, was found the hard way to be only six feet (1.9m). Some of the Army ships drew too much to get across, and had to be

kedged in after being lightened. Others were too deep even to be kedged in; the men or materials they carried had to be brought

ashore on Hatteras Island, and the ships sent back. Bark John Trucks never made it at all;

she could not get close enough to Hatteras Island even for the men aboard to be taken off.

She returned to Annapolis with an entire regiment, the Fifty-third

New York, who thereby missed the battle. Not until 4 February was the fleet as ready as it ever would be and assembled in

Pamlico Sound.

While the Northern fleet

was struggling over the bar, the Rebels were strangely inert. No reinforcements were sent to the island, or, for that matter,

any of the other possible targets in the region. The number of infantrymen on the island remained at about 1400, with 800

in reserve at Nag's Head. The major change was negative: on 1 February, General Wise came down with what he called "pleurisy,

with high fever and spitting of blood, threatening pneumonia." He was confined to bed at Nag's Head, and remained hospitalized

until 8 February, after the battle was over. Although he continued to issue orders, effective command on Roanoke

Island fell to Colonel H. M. Shaw of the Eighth North Carolina Infantry.

| Roanoke Island and the Outer Banks |

|

| Battle of Roanoke Island |

| Roanoke Island, North Carolina |

|

| Map of the strategic Roanoke, Island, North Carolina |

| North Carolina Civil War Battles Map |

|

| (Click to Enlarge) |

First

Day: Bombardment

The fleet got under way early the next morning

(5 February), and by nightfall were near the southern end of Roanoke Island, where they anchored.

Rain and strong winds prevented movements the next day. The major activity was Goldsborough's shift of his flag from USS Philadelphia

to Southfield. On 7 February the weather moderated, and the

Navy gunboats got into position. They first fired a few shells inland at Ashby

Harbor, the intended landing place, and determined that the defenders

had no batteries there. They then moved up Croatan Sound, where they were divided; some were ordered to fire on the fort at

Pork Point (Fort Bartow),

while others were to concentrate their fire on the seven vessels of the Mosquito Fleet. At about noon, the bombardment began.

The weakness of the

Confederate position became manifest at this time. Only four of the guns at Fort

Bartow would bear on the Union gunboats. Forts Huger and Blanchard could

not contribute at all. Fort Forrest,

on the other side of the sound, was rendered completely useless when gunboat CSS Curlew, holed at the waterline, ran ashore

directly in front in her effort to avoid sinking, and in so doing masked the guns of the fort.

Losses were light

on both sides despite the intensity of the fight. Several of the Federal ships were hit, but none suffered severe damage.

This was true for the Rebels also, aside from Curlew, but the remaining Mosquito Fleet had to retire simply because they ran

out of ammunition.

The Army transports,

accompanied by its gunboats, had in the meantime arrived at Ashby

Harbor, near the midpoint of the island. At 1500, Burnside ordered the

landings to begin, and at 1600 the troops were reaching shore. A 200-man strong Rebel force commanded by Col. John V. Jordan

(31st North Carolina), in position to oppose the landing,

was discovered and fired on by the gunboats; the defenders fled without any attempt to return fire. There was no further opposition.

Almost all of the 10000 men present were ashore by midnight. With the infantry went six launches with boat howitzers, commanded

by a young midshipman, Benjamin H. Porter. The Yankees pushed inland a short distance and then went into camp for the night.

| Vintage Civil War Map of Battle of Roanoke Island |

|

| Period Map of Roanoke Island |

Second Day: Union Advance and Confederate Surrender The Federal soldiers moved out promptly on the morning of 8

February, advancing north on the only road on the island. Leading was the First Brigade's 25thMassachusetts, with Midshipman Porter's howitzers immediately following. They were soon

halted, when they struck the Confederate redoubt and some 400 infantry blocking their path. Another thousand Rebels were in

reserve, about 250 yards (230 m) to the rear; the front was so constricted that Colonel Shaw could deploy only a quarter of

his men. The defensive line ended in what were deemed impenetrable swamps on both sides, so Shaw did not protect his flanks. The leading elements of the First Brigade spread out to match

their opponents' configuration, and for two hours the combatants fired at each other through blinding clouds of smoke. The

10th Connecticut relieved the exhausted, but not badly bloodied, 25th Massachusetts, but they too could not advance. No progress was made

until the Second Brigade arrived, and its commander, Brig. Gen. Reno, ordered them to try to penetrate the impenetrable swamp

on the Union left. Brig. Gen. Foster then ordered two of his reserve regiments

to do the same on the right. About this time, Brig. Gen. Parke came up with the Third Brigade, and it was immediately sent

to assist. Although they were not coordinated, the two flanking movements emerged from the swamp at nearly the same time. Reno ordered his 21st Massachusetts, 51st New York, and 9th New Jersey to

attack. As they were firing on the Confederates, the 23rd Massachusetts,

from the First Brigade, appeared on the other end of the line. The defensive line began to crack; noting this, Foster ordered

his remaining forces to attack. Under assault from three sides, the Rebels broke and fled. As no fall-back defenses had been set up, and he was bereft

of artillery, Col. Shaw surrendered to Foster. Included in the capitulation were not only the 1400 infantry that he commanded

directly, but also the guns in the forts. Two additional battalions (2nd North

Carolina and 46th Virginia) had been sent as reinforcements. They arrived too late to take part

in the battle, but not too late to be take part in the surrender. Altogether, some 2500 men became prisoners of war. Aside from the men who went into captivity, casualties were

rather light by Civil War standards. The Federal forces lost 37 killed, 214 wounded, and 13 missing. The Confederates lost

23 killed, 58 wounded, and 62 missing.

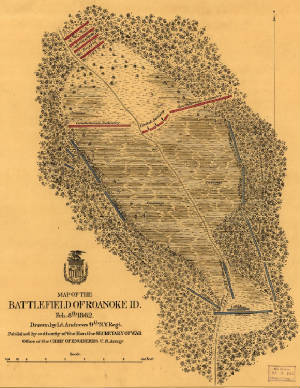

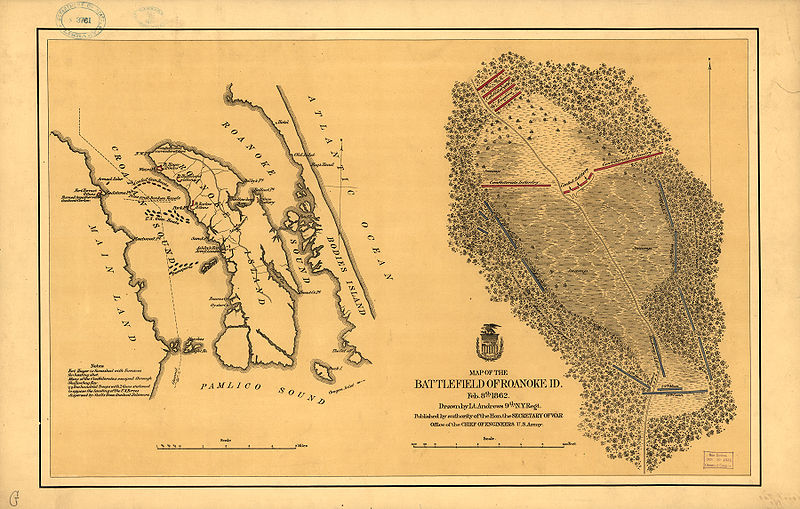

| Historic Roanoke Island Battlefield Map |

|

| Roanoke Island Battlefield Map |

(About) Map of Roanoke Island, showing forts and fleet dispositions, February

7, 1862, on the left, and on the right, the battlefield where opposing armies met on February 8. Prepared by Lt. Andrews,

9th N.Y. Regiment. Library of Congress.

Aftermath

Roanoke

Island remained in Federal control for the rest of the Civil War. Immediately after the battle, the Federal gunboats

passed the now-silent Confederate forts into Albemarle Sound, and destroyed what was left

of the Mosquito Fleet at the Battle of Elizabeth City. Burnside used the island as staging ground for later assaults on New Bern and Fort Macon, resulting

in their capture. Several minor expeditions took other towns on the sounds. The Burnside Expedition ended only in July, when

its leader was called to Virginia to take part in the Richmond

campaign.

After Burnside withdrew,

North Carolina ceased to be an active center of the war.

With only one or two exceptions, nothing notable took place until the last days of the war, when the Battle of Fort Fisher

closed Wilmington, the last port in the Confederacy.

Opposing Forces:

Union and Confederate Orders of Battle

Union Order of

Battle

Coast Division (Brig.

Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside)

First Brigade (Brig.

Gen. John G. Foster)

10th Connecticut

23rd Massachusetts

24th Massachusetts

25th Massachusetts

27th Massachusetts

Second Brigade (Brig.

Gen. Jesse L. Reno)

21st Massachusetts

9th New Jersey

51st New York

51st Pennsylvania

Third Brigade {Brig.

Gen. John G. Parke)

8th Connecticut

11th Connecticut (not in Battle of Roanoke Island)

9th New York

4th Rhode Island

5th Rhode Island

Unassigned units:

1st New York Marine

Artillery (detachment)

99th New York (Union Coast Guard)

Army gunboats:

Picket

Vidette

Hussar

Lancer

Ranger

Chasseur

Pioneer

Sentinel

Union Navy

North

Atlantic Blockading Squadron (Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough)

Philadelphia (not used in Battle of Roanoke Island)

Stars and Stripes

Louisiana

Hetzel

Underwriter

Delaware

Commodore Perry

Valley City

Commodore Barney

Hunchback

Southfield (flagship during battle)

Morse

Whitehead

Lockwood

Henry Brinker

Isaac N. Seymour

Ceres

Putnam

Shawsheen

Granite

Confederate Order

of Battle

— Brig. Gen.

Henry A. Wise (not present in battle; ill)

Col. H. M. Shaw, second

in command

2nd North Carolina

8th North Carolina

17th

North Carolina (3 companies)

31st North Carolina

46th Virginia

59th Virginia

(The Virginia regiments were part of the Wise Legion)

Confederate Navy

"Mosquito Fleet" (Flag

Officer William F. Lynch)

Sea-Bird (flagship)

Curlew (sunk)

Ellis

Beaufort

Raleigh

Fanny

Forrest

Appomattox (not at Battle of Roanoke Island)

(References located

at bottom of page.)

Recommended

Reading: The Civil War on Roanoke Island North Carolina:

Portrait of the Past (Hardcover). Description:

Even though the Civil War on Hatteras Island ended with the capture of Hatteras by Union

forces, the Outer Banks role in the war continued. Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside continued his expedition into Roanoke

Island in 1862, along with flag officer L. J. Goldsborough, Colonel Rush Hawkins of the Ninth New York Zouaves, and many others,

causing great upheaval and dissonance to the simple lives of the islanders. Continued below...

The pictures

can almost tell the story, but the rich historical detail in the text is absolutely fascinating. This book features drawings

by James Wells Champney, who was also stationed at Fort Macon

in the Outer Banks with the Union forces. In addition, journal entries and personal correspondence of soldiers such as Charles

F. Johnson and Capt. William Chase (of the 4th Rhode Island)

and the development of freedom's colony allow the reader a truly personal look into the soldiers' lives during these trying

times.

Recommended Reading: The

Civil War on the Outer Banks: A History of the Late Rebellion Along the Coast of North Carolina from Carteret to Currituck

With Comments on Prewar Conditions and an Account of (251 pages). Description: The ports at Beaufort, Wilmington, New Bern and Ocracoke, part of the Outer Banks (a chain

of barrier islands that sweeps down the North Carolina coast from the Virginia Capes to Oregon Inlet), were strategically

vital for the import of war materiel and the export of cash producing crops. Continued below...

From official records, contemporary newspaper accounts, personal journals of the soldiers, and many unpublished

manuscripts and memoirs, this is a full accounting of the Civil War along the

North Carolina coast.

Recommended Reading: Storm over Carolina: The Confederate Navy's

Struggle for Eastern North Carolina. Description: The struggle for control of the eastern waters of North Carolina during the War Between the States was a bitter, painful, and sometimes humiliating

one for the Confederate navy. No better example exists of the classic adage, "Too little, too late." Burdened by the

lack of adequate warships, construction facilities, and even ammunition, the South's naval arm fought bravely and even recklessly

to stem the tide of the Federal invasion of North Carolina from the raging Atlantic.

Storm Over Carolina is the account of the Southern navy's struggle in North Carolina waters and it is a saga of crushing defeats interspersed

with moments of brilliant and even spectacular victories. It is also the story of dogged Southern determination and incredible

perseverance in the face of overwhelming odds. Continued below...

For most of

the Civil War, the navigable portions of the Roanoke, Tar, Neuse, Chowan, and Pasquotank rivers were

occupied by Federal forces. The Albemarle and Pamlico sounds, as well as most of the coastal towns and counties, were also

under Union control. With the building of the river ironclads, the Confederate navy at last could strike a telling blow against

the invaders, but they were slowly overtaken by events elsewhere. With the war grinding to a close, the last Confederate vessel

in North Carolina waters was destroyed. William T. Sherman

was approaching from the south, Wilmington was lost, and the

Confederacy reeled as if from a mortal blow. For the Confederate navy, and even more

so for the besieged citizens of eastern North Carolina,

these were stormy days indeed. Storm Over Carolina describes their story,

their struggle, their history.

Recommended Reading:

Ironclads and Columbiads: The Coast (The Civil War in North Carolina) (456 pages). Description: Ironclads and Columbiads covers some of the most important battles and campaigns in

the state. In January 1862, Union forces began in earnest to occupy crucial points on the North Carolina coast. Within six months, Union army and naval forces effectively controlled

coastal North Carolina from the Virginia line south to present-day

Morehead City.

Continued below...

Union setbacks in Virginia, however, led to the withdrawal of many federal

soldiers from North Carolina, leaving only enough Union troops to hold a few coastal strongholds—the vital ports and

railroad junctions. The South during the Civil War, moreover, hotly contested the North’s ability to maintain its grip

on these key coastal strongholds.

References: Burnside, Ambrose

E., "The Burnside Expedition," Battles and leaders of the Civil War, Johnson, Robert Underwood, and Clarence Clough Buell,

eds. New York:Century,

1887–1888; reprint, Castle, n.d.; Browning, Robert M. Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear:

the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Univ. of Alabama, 1993; Campbell, R. Thomas, Storm over Carolina: the Confederate

Navy's struggle for eastern North Carolina. Cumberland House,

2005; Miller, James M., The Rebel shore: the story of Union sea power in the Civil War. Little, Brown and Co., 1957; Trotter,

William R., Ironclads and Columbiads: the Coast. Joseph F. Blair, 1989; US Navy Department, Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. Series I: 27 volumes. Series II: 3 volumes.

Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922; US War Department, A compilation

of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I: 53 volumes. Series

II: 8 volumes. Series III: 5 volumes. Series IV: 4 volumes. Washington:

Government Printing Office, 1886–1901; Microsoft MapPoint; Microsoft Virtual Earth Map (2D): Microsoft Virtual

Earth Map (3D); NASA Maps; Library of Congress.

|