|

"Compromise of 1850, Fugitive Slave Act, and

Expansion of Slavery Results"

The Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act (aka

Fugitive Slave Law of 1850)

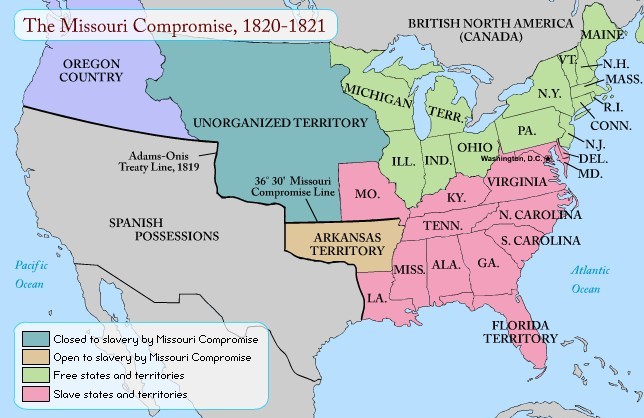

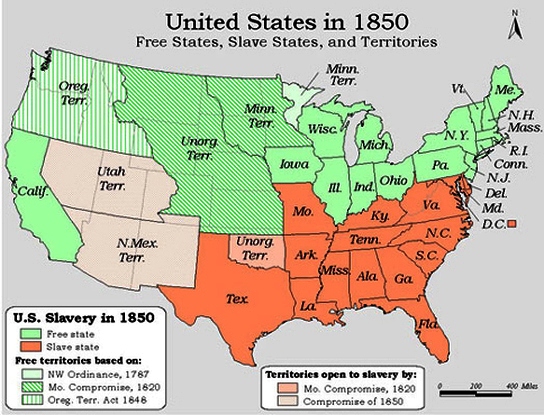

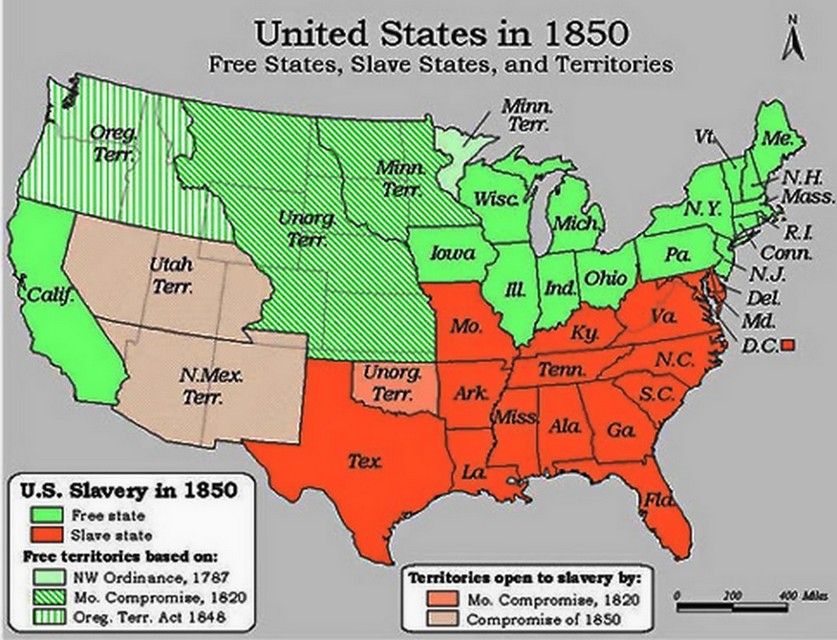

| The Compromise of 1850 Map |

|

| Compromise of 1850 Map of States |

| Compromise of 1850 Map and Evolution of Slavery |

|

| Slavery Compromise Map and Compromise of 1850 Map. Expansion and Abolition of Slavery Map. |

| Compromise of 1850 and Missouri Compromise Map |

|

| Compromise of 1850 followed the failed Missouri Compromise of 1820 |

Compromise of 1850 and Fugitive Slave Act: A History

What was the Compromise of 1850?

Although the Compromise of 1850 consisted

of five bills which were drafted to address slavery, its goal was to create and maintain a balance between the slave

and free states. Prior to the Compromise, the nation hosted 15 free and 15 slave states, allowing an equitable balance

of political power between the North and South. Although congressman and senators from both Northern and Southern states engaged

in contentious debates over the expansion of slavery into new territory, the masses in both sections of the country believed

that the Compromise and its five bills did not address their deeper concerns on whether the nation would continue to support

slavery or abolish the institution altogether. While the Northern states were overwhelmingly antislavery, the

South was proslavery and believed that the institution should strictly be left to the states to decide.

In just eleven years, in 1861, both portions of the nation would decide the issue on the battlefield during the American Civil

War (1861-1865).

What Caused the Compromise of 1850?

The Compromise of 1850 was caused by the purchase of 55% of the territory

of Mexico by the United States at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and according to terms

agreed upon in the Mexican Cession of 1848. In merely four years, from Texas statehood in 1845 to the territory gained by the Mexican

Cession in 1848, the United States had expanded its borders by more than 60%, and now spanned from coast to coast and from

sea to shining sea.

Results of the Compromise of

1850

The main result of the Compromise was that it failed to create the balance

between free and slave states in the United States. As a result, the balance of political and economical power favored

the North, causing sectionalism. Immediately following the vast territory purchased from Mexico in the Mexican Cession of

1848, Washington debated whether or not the territory should be carved into slave or free states. Subsequent to the Compromise

of 1850, California was admitted to the Union as a free state in 1850, followed by three additional free states with Minnesota

in 1858, Oregon in 1859, and Kansas in 1861. No slave states were added to the United States during that time,

so the nation was now confronted with an imbalance of power with 15 slave and 19 free states, known as

sectionalism, which served only to fuel existing tensions between the North and

South. The Mexican Cession resulted in the Compromise of 1850 and the rapid shift in political power and influence.

Because the Compromise of 1850 failed to maintain an equitable balance, it stoked the flames of sectionalism

and secession, and in just eleven years, 1861, the nation would be engaged in bloody Civil War.

Summary

Henry Clay, U.S. senator from Kentucky,

was determined to find a solution to the slavery crisis. In 1820, he had resolved a fiery debate over the spread of slavery

with his Missouri Compromise. Now, thirty years later, the subject resurfaced within the walls of the Capitol. But this time the stakes were higher,

and while the drums of secession were beater louder in the halls of Congress, Clay understood that the

preservation of the Union was at stake. The Compromise of 1850 consisted of five bills, including the contentious

Fugitive Slave Act, which, among other points, required citizens to cooperate in apprehending runaway slaves.

The Compromise of 1850 was a series of five bills which passed by the U.S. Congress during September 1850. These measures, essentially

the work of Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, were designed to reconcile the political differences dividing the antislavery

and proslavery factions of Congress and the nation. The measures, sometimes referred to collectively as the Omnibus Bill,

dealt chiefly with the question of whether slavery was to be sanctioned or prohibited in the regions acquired from Mexico

as a result of the Mexican War (1846-1848). Two of the five measures represented concessions by the South to the North, authorizing

the abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia and admission of California as a free state. The third bill,

a substantial concession to the South, was the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which provided for the return of runaway slaves to their masters. By the terms of the fourth measure, the territory

east of California ceded to the U.S. by Mexico was divided into the territories of New Mexico (now New Mexico and Arizona)

and Utah, and they were open to settlement by both slave-holders and antislavery settlers. This Compromise superseded the

Missouri Compromise of 1820, which was later repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The fifth measure provided that Texas, already in the Union as a slave state, be awarded $10 million in settlement of claims

to adjoining territories, further strengthening the South.

| Compromise of 1850 and Fugitive Slave Act Map |

|

| Map of Compromise of 1850 and Fugitive Slave Law. Courtesy Bing.com. |

Several Points Debated

¥ The United States had recently acquired a vast

territory as a result of the Mexican American War. Should the territory allow slavery, or should it

be declared free? See also Slave Trade, Slavery, and Early Antislavery. Or maybe the inhabitants should be allowed to choose for themselves? See Popular Sovereignty and Mexican Cession.

¥ California -- a territory

that had grown tremendously with the gold rush of 1849, had recently petitioned Congress to enter the Union as a free state. Should this be allowed? Ever since the Missouri Compromise,

the balance between slave states and free states had been

maintained; any proposal that threatened this balance would almost certainly not win approval.

¥ There was a dispute

over land: Texas claimed that its territory extended all the way to Santa Fe. See Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

¥ Finally, there

was Washington, D.C. Not

only did the nation's capital allow slavery, it was home to the largest slave market in North America.

History

On January 29, 1850, the 70-year-old

Clay presented a compromise. For eight months members of Congress, led by Clay, Daniel Webster, Senator from Massachusetts,

and John C. Calhoun, senator from South Carolina, debated

the compromise. With the help of Stephen Douglas, a young Democrat from Illinois,

a series of bills that would make up the compromise were ushered through Congress.

According to the compromise, Texas would relinquish the land in dispute but, in compensation, be given 10 million dollars -- money

it would use to pay off its debt to Mexico.

Also, the territories of New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah would be organized

without mention of slavery. (The decision would be made by the territories' inhabitants later, when they applied for statehood.)

Regarding Washington, the slave trade would be abolished in the District of Columbia, although slavery would still be permitted. Finally, California

would be admitted as a free state. To pacify slave-state

politicians, who would have objected to the imbalance created by adding another free

state, the Fugitive Slave Act was passed.

Of all the bills that comprised the Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was the most controversial. It required citizens to assist in the recovery of

fugitive slaves. It denied a fugitive's right to a jury trial. (Cases would instead be handled by special commissioners --

commissioners who would be paid $5 if an alleged fugitive were released and $10 if he or she were sent away with the claimant.)

The act called for changes in filing for a claim, making the process easier for slaveowners. Also, according to the act, there

would be more federal officials responsible for enforcing the law.

For slaves attempting to build

lives in the North, the new law was disaster. Many left their homes and fled to Canada.

During the next ten years, an estimated 20,000 blacks moved to the neighboring country. For Harriet Jacobs, a fugitive living

in New York, passage of the law was "the beginning of a

reign of terror to the colored population." She stayed put, even after learning that slave catchers were hired to track her

down. Anthony Burns, a fugitive living in Boston, was one

of many who were captured and returned to slavery. Free blacks, too, were captured and sent to the South. With no legal right

to plead their cases, they were completely defenseless.

Passage of the Fugitive Slave Act made abolitionists all the

more resolved to put an end to slavery. The Underground Railroad became more active, reaching its peak between 1850 and 1860.

The act also brought the subject of slavery before the nation. Many who had previously been ambivalent about slavery now took

a definitive stance against the institution.

The Compromise of 1850 accomplished what it set out to do -- it kept

the nation united -- but the solution was only temporary. Over the following decade the country's citizens became further

divided over the issue of slavery. The rift would continue to grow until the nation itself divided.

The Compromise of 1850 brought

relative calm to the nation. Though most blacks and abolitionists strongly opposed the Compromise, the majority of Americans embraced it, believing

that it offered a final, workable solution to the slavery question. Most importantly, it saved the Union from the terrible

split that many had feared. People were all too ready to leave the slavery controversy behind them and move on. But the feeling

of relief that spread throughout the country would prove to be the calm before the storm. See also famous abolitionists.

| Compromise of 1850 Map and Popular Sovereignty Map |

|

| Compromise of 1850, Free States, Slave States, and Popular Sovereignty Map |

On December 14, 1853, Augustus C. Dodge of Iowa introduced a bill

in the Senate. The bill proposed organizing the Nebraska territory, which also included an area that would become the state

of Kansas. His bill was referred to the Committee of the Territories, which was chaired by Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois.

Douglas had entered politics

early and had advanced quickly; at 21 he was Illinois state's attorney, and by age 35 he was a U.S. Senator. He strongly endorsed

the idea of popular sovereignty, which allowed the settlers in a territory to decide for themselves whether or not to have slavery (see Compromise of 1850 and Popular Sovereignty Map). Douglas was also a fervent advocate of Manifest Destiny, the idea that the United States had the God-given right and obligation to take over as much land as possible and

to spread its "civilizing" influence. And he was not alone. A Philadelphia newspaper expounded Manifest Destiny when it proclaimed

the United States to be a nation rightfully bound on the "East by sunrise, West by sunset, North by the Arctic Expedition,

and South as far as we darn please."

To fulfill its Manifest Destiny, especially following the discovery of gold in

California, America was making plans to build a transcontinental railroad from east to west. The big question was where to

locate the eastern terminal -- to the north, in Chicago, or to the south, in St. Louis. Douglas was firmly committed to ensuring

that the terminal would be in Chicago, but he knew that it could not be unless the Nebraska territory was organized.

Organization

of Nebraska would require the removal of the territory's Native Americans, for Douglas regarded the Indians as savages, and

saw their reservations as "barriers of barbarism." In his view, Manifest Destiny required the removal of those who stood in

the way of American, Christian progress, and the Native American presence was a minor obstacle to his plans. But there was

another, larger problem.

In order to get the votes he needed, Douglas had to please Southerners. He therefore bowed

to Southern wishes and proposed a bill for organizing Nebraska-Kansas which stated that the slavery question would be decided

by popular sovereignty. He assumed that settlers there would never choose slavery, but did not anticipate the vehemence of

the Northern response. This bill, if made into law, would repeal the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which said that slavery

could not extend above the 36' 30" line. It would open the North to slavery. Northerners were outraged; Southerners were overjoyed.

| Compromise of 1850 Map and Fugitive Slave Law |

|

| Slavery Compromise of 1850 Map, Fugitive Slave Act, and Free and Slave States Map |

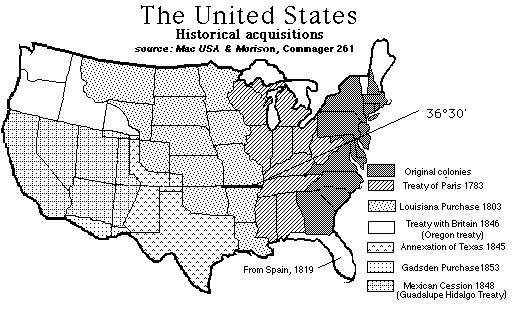

| Compromise Act of 1850 Lesson Plan for Kids |

|

| What Caused the Compromise of 1850? Territory purchased by the US in 1848. |

Douglas was stubborn. Ignoring

the anger of his own party, he got President Pierce's approval and pushed his bill through both houses of Congress. The bill,

the Kansas-Nebraska Act, became law on May 30, 1854.

Nebraska was so far north that its future as a free state was never in question.

But Kansas was next to the slave state of Missouri. In an era that would come to be known as "Bleeding Kansas," the territory would become a battleground over the slavery question.

The reaction from the North was immediate.

Eli Thayer organized the New England Emigrant Aid Company, which sent settlers to Kansas to secure it as a free territory.

By the summer of 1855, approximately 1,200 New Englanders had made the journey to the new territory, armed to fight for freedom.

The abolitionist minister Henry Ward Beecher furnished settlers with Sharps rifles, which came to be known as "Beecher's Bibles."

Rumors had spread through the South that 20,000 Northerners were descending on Kansas, and in November 1854, thousands

of armed Southerners, mostly from Missouri, poured over the line to vote for a proslavery congressional delegate. Only half

the ballots were cast by registered voters, and at one location, only 20 of over 600 voters were legal residents. The proslavery

forces won the election.

On March 30, 1855, another election was held to choose members of the territorial legislature.

The Missourians, or "Border Ruffians," as they were called, again poured over the line. This time, they swelled the numbers

from 2,905 registered voters to 6,307 actual ballots cast. Only 791 voted against slavery.

The new state legislature

enacted what Northerners called the "Bogus Laws," which incorporated the Missouri slave code. These laws leveled severe penalties

against anyone who spoke or wrote against slaveholding; those who assisted fugitives would be put to death or sentenced to

ten years hard labor. (Statutes of Kansas) The Northerners were outraged, and set up their own Free State legislature at Topeka.

Now there were two governments established in Kansas, each outlawing the other. President Pierce only recognized the proslavery

legislature.

Most settlers who had come to Kansas from the North and the South only wanted to homestead in peace. They

were not interested in the conflict over slavery, but they found themselves in the midst of a battleground. Violence erupted

throughout the territory. Southerners were driven by the rhetoric of leaders such as David Atchison, a Missouri senator. Atchison

proclaimed the Northerners to be "negro thieves" and "abolitionist tyrants." He encouraged Missourians to defend their institution

"with the bayonet and with blood" and, if necessary, "to kill every God-damned abolitionist in the district."

The

northerners, however, were not all abolitionists as Atchison claimed. In fact, abolitionists were in the minority. Most of

the Free State settlers were part of a movement called Free Soil, which demanded free territory for free white people. They

hated slavery, but not out of concern for the slaves themselves. They hated it because plantations took over the land and

prevented white working people from having their own homesteads. They hated it because it brought large numbers of black people

wherever it went. The Free Staters voted 1,287 to 453 to outlaw black people, slave or free, from Kansas. Their territory

would be white.

| Slavery Compromise Map and Fugitive Slave Act |

|

| Slavery Compromise of 1850 and Fugitive Slave Act Map |

| Slavery Compromise of 1850 Map |

|

| Compromise of 1850 Map |

As the two factions struggled for control of the territory, tensions increased. In 1856 the proslavery territorial

capital was moved to Lecompton, a town only 12 miles from Lawrence, a Free State stronghold. In April of that year a three-man

congressional investigating committee arrived in Lecompton to look into the Kansas troubles. The majority report of the committee

found the elections to be fraudulent, and said that the free state government represented the will of the majority. The federal

government refused to follow its recommendations, however, and continued to recognize the proslavery legislature as the legitimate

government of Kansas.

There had been several attacks during this time, primarily of proslavery against Free State men.

People were tarred and feathered, kidnapped, killed. But now the violence escalated. On May 21, 1856, a group of proslavery

men entered Lawrence, where they burned the Free State Hotel, destroyed two printing presses, and ransacked homes and stores.

In retaliation, the fiery abolitionist John Brown led a group of men on an attack at Pottawatomie Creek. The group, which included four of Brown's sons,

dragged five proslavery men from their homes and hacked them to death.

The violence had now escalated, and the confrontations

continued. John Brown reappeared in Osawatomie to join the fighting there. Violence also erupted in Congress itself. The abolitionist

senator Charles Sumner delivered a fiery speech called "The Crime Against Kansas," in which he accused proslavery senators,

particularly Atchison and Andrew Butler of South Carolina, of [cavorting with the] "harlot, Slavery." In retaliation, Butler's

nephew, Congressman Preston Brooks, attacked Sumner at his Senate desk and beat him senseless with a cane.

In September

of 1856, a new territorial governor, John W. Geary, arrived in Kansas and began to restore order. The last major outbreak

of violence was the Marais des Cynges massacre, in which Border Ruffians killed five Free State men. In all, approximately 55 people died in "Bleeding

Kansas."

Several attempts were made to draft a constitution which Kansas could use to apply for statehood. Some versions

were proslavery, others free state. Finally, a fourth convention met at Wyandotte in July 1859, and adopted a free state constitution.

Kansas applied for admittance to the Union. However, the proslavery forces in the Senate strongly opposed its free state status,

and stalled its admission. Only in 1861, after the Confederate states seceded, did the constitution gain approval and Kansas

become a state.

Sources: Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) Online; Library of Congress;

National Park Service; National Archives; Bing.com.

Recommended Reading: Henry

Clay: Statesman for the Union. From Library Journal: Award-winning historian Remini has written the definitive biography on controversial

19th-century politician Henry Clay of Kentucky. Remini's

work, which uses a rich array of primary sources, especially letters uncovered by the Henry Clay Papers publication project,

surpasses earlier studies of Clay by Glyndon Van Deusen (The Life of Henry Clay, Greenwood, 1979) and Clement Eaton (Henry

Clay & the Art of American Politics, 1962). All facets of Clay's life are examined, especially much new information about

his private life and how it influenced his public political career. Remini analyzes why an accomplished political leader such

as Clay could never be elected president, though he ran for the office five times. Continued below….

Clay's political

success came from his extraordinary talents as the engineer who directed three major compromises between 1820 and 1850 through

Congress, thus averting civil strife and keeping the Union together. This is an

excellently written, superbly crafted, and long-needed biography that is suitable for academic and large public libraries.

Recommended Reading:

The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861

(Paperback), by David M. Potter. Review: Professor Potter treats an incredibly complicated and misinterpreted time period with unparalleled

objectivity and insight. Potter masterfully explains the climatic events that led to Southern secession – a greatly

divided nation – and the Civil War: the social, political and ideological conflicts; culture; American expansionism,

sectionalism and popular sovereignty; economic and tariff systems; and slavery. In other words, Potter places under the microscope the root causes and origins of

the Civil War. He conveys the subjects in easy to understand language to edify the reader's

understanding (it's not like reading some dry old history book). Delving

beyond surface meanings and interpretations, this book analyzes not only the history, but the historiography of the time period

as well. Continued below…

Professor Potter

rejects the historian's tendency to review the period with all the benefits of hindsight. He simply traces the events, allowing

the reader a step-by-step walk through time, the various views, and contemplates the interpretations of contemporaries and

other historians. Potter then moves forward with his analysis. The Impending Crisis is the absolute gold-standard of historical

writing… This simply is the book by which, not only other antebellum era books, but all history books should be judged.

Recommended Reading: Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States) (Hardcover: 904 pages). Description: Published in 1988 to universal acclaim, this

single-volume treatment of the Civil War quickly became recognized as the new standard in its field. James M. McPherson, who won the Pulitzer Prize for this book, impressively combines a brisk writing style

with an admirable thoroughness. James McPherson's fast-paced narrative fully integrates the political, social, and military

events that crowded the two decades from the outbreak of one war in Mexico

to the ending of another at Appomattox. Packed with drama

and analytical insight, the book vividly recounts the momentous episodes that preceded the Civil War including the Dred Scott

decision, the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry. It flows into a masterful chronicle of the

war itself--the battles, the strategic maneuvering by each side, the politics, and the personalities. Continued below...

Particularly notable are McPherson's new views on such matters as Manifest Destiny, Popular Sovereignty,

Sectionalism, and slavery expansion issues in the 1850s, the origins of the Republican Party, the causes of secession,

internal dissent and anti-war opposition in the North and the South, and the reasons for the Union's victory. The book's title refers to the sentiments that informed both the Northern and Southern

views of the conflict. The South seceded in the name of that freedom of self-determination and self-government for which their

fathers had fought in 1776, while the North stood fast in defense of the Union founded by

those fathers as the bulwark of American liberty. Eventually, the North had to grapple with the underlying cause of the war,

slavery, and adopt a policy of emancipation as a second war aim. This "new birth of freedom," as Lincoln

called it, constitutes the proudest legacy of America's

bloodiest conflict. This authoritative volume makes sense of that vast and confusing "second American Revolution" we call

the Civil War, a war that transformed a nation and expanded our heritage of liberty. . Perhaps more than any other book, this one belongs on the bookshelf of every Civil War buff.

Recommended Reading:

What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford History of the United States) (Hardcover: 928 pages). Review: The newest volume in the renowned

Oxford History of the United States-- A brilliant portrait of an era that saw dramatic transformations in American life The

Oxford History of the United States is

by far the most respected multi-volume history of our nation. The series includes two Pulitzer Prize winners, two New York

Times bestsellers, and winners of the Bancroft and Parkman Prizes. Now, in What Hath God Wrought, historian Daniel Walker

Howe illuminates the period from the battle of New Orleans to the end of the Mexican-American

War, an era when the United States expanded

to the Pacific and won control over the richest part of the North American continent. Continued below…

Howe's panoramic

narrative portrays revolutionary improvements in transportation and communications that accelerated the extension of the American

empire. Railroads, canals, newspapers, and the telegraph dramatically lowered travel times

and spurred the spread of information. These innovations prompted the emergence of mass political parties and stimulated America's

economic development from an overwhelmingly rural country to a diversified economy in which commerce and industry took their

place alongside agriculture. In his story, the author weaves together political and military events with social, economic,

and cultural history. He examines the rise of Andrew Jackson and his Democratic party, but contends that John Quincy Adams

and other Whigs--advocates of public education and economic integration, defenders of the rights of Indians, women, and African-Americans--were

the true prophets of America's future.

He reveals the power of religion to shape many aspects of American life during this period, including slavery and antislavery,

women's rights and other reform movements, politics, education, and literature. Howe's story of American expansion -- Manifest

Destiny -- culminates in the bitterly controversial but brilliantly executed war waged against Mexico

to gain California and Texas for the United States. By 1848, America

had been transformed. What Hath God Wrought provides a monumental narrative of this formative period in United States history.

Recommended Reading: Abraham

Lincoln: Redeemer President (Library of Religious Biography).

Description: Since its original publication in 1999, "Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President" has garnered numerous accolades,

including the prestigious 2000 Lincoln Prize. Allen Guelzo's peerless biography of America's most celebrated president is now available for the first time in a fine

paperback edition. The first "intellectual biography" of Lincoln, this work explores the role

of ideas in Lincoln's life, treating him as a serious thinker

deeply involved in the nineteenth-century debates over politics, religion, and culture. Written with passion and dramatic

impact, Guelzo's masterful study offers a revealing new perspective on a man whose life was in many ways a paradox. As journalist

Richard N. Ostling notes, "Much has been written about Lincoln's

belief and disbelief," but Guelzo's extraordinary account "goes deeper."

Recommended Reading: Slavery and Politics in the Early American Republic.

Description: Giving close consideration to previously

neglected debates, Matthew Mason challenges the common contention that slavery held little political significance in America until the Missouri Crisis. Mason demonstrates

that slavery and politics were enmeshed in the creation of the nation, and in fact there was never a time between the Revolution

and the Civil War in which slavery went uncontested. Continued below...

The American

Revolution set in motion the split between slave states and free states, but Mason explains that the divide took on

greater importance in the early nineteenth century. He examines the partisan and geopolitical uses of slavery, the conflicts

between free states and their slaveholding neighbors, and

the political impact of African Americans across the country. Offering a full picture of the politics of slavery in the crucial

years of the early republic, Mason demonstrates that partisans and patriots, slave and

free—and not just abolitionists and advocates of slavery—should be considered important players in the politics

of slavery in the United States.

Recommended Reading:

Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Defined America (Simon & Schuster) (February

5, 2008) (Hardcover). Description: In 1858, Abraham

Lincoln was known as a successful Illinois lawyer who had

achieved some prominence in state politics as a leader in the new Republican Party. Two years later, he was elected president

and was on his way to becoming the greatest chief executive in American history. What carried this one-term congressman from

obscurity to fame was the campaign he mounted for the United States Senate against the country's most formidable politician,

Stephen A. Douglas, in the summer and fall of 1858. Lincoln challenged Douglas directly in

one of his greatest speeches -- "A house divided against itself cannot stand" -- and confronted Douglas on the questions of

slavery and the inviolability of the Union in seven fierce debates. As this brilliant narrative

by the prize-winning Lincoln scholar Allen Guelzo dramatizes, Lincoln would emerge a predominant national figure, the leader of his party, the man who

would bear the burden of the national confrontation. Continued below...

Of course,

the great issue between Lincoln and Douglas was slavery. Douglas was the champion of "popular sovereignty," of letting states and territories decide

for themselves whether to legalize slavery. Lincoln drew a

moral line, arguing that slavery was a violation both of natural law and of the principles expressed in the Declaration of

Independence. No majority could ever make slavery right, he argued. Lincoln lost that Senate

race to Douglas, though he came close to toppling the "Little Giant," whom almost everyone

thought was unbeatable. Guelzo's Lincoln and Douglas brings alive their debates and this whole year of campaigns and underscores

their centrality in the greatest conflict in American history. The encounters between Lincoln and Douglas engage a key question

in American political life: What is democracy's purpose? Is it to satisfy the desires of the majority? Or is it to achieve

a just and moral public order? These were the real questions in 1858 that led to the Civil War. They remain questions for

Americans today.

|